Summary:

- Tesla’s “Full Self-Driving” feature is not actually fully autonomous, and yet the company charges customers for it.

- The problem of fully autonomous driving is challenging due to Moravec’s paradox and the limitations of current AI technology.

- Tesla’s pivot to end-to-end learning for self-driving cars may be seen as a desperate move, and the prospects for its humanoid robot prototype, Optimus, are dim.

Justin Sullivan

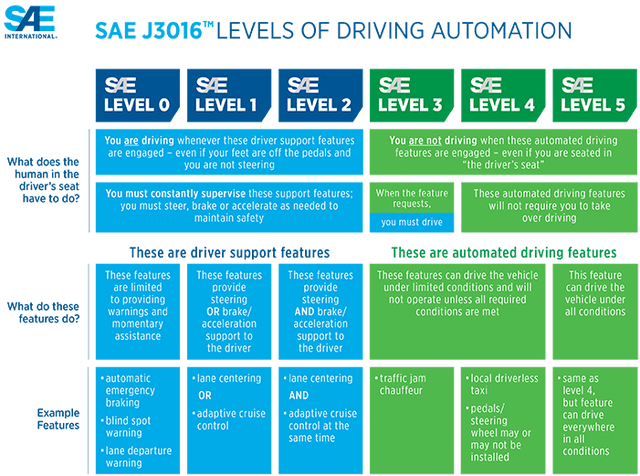

Since 2016, Tesla, Inc. (NASDAQ:TSLA) has been continually promising that its production cars would be capable of fully autonomous driving – what the Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE) calls “Level 4” or “Level 5,” according to this schema:

Chart of SAE Levels of Automation. (Society of Automotive Engineers)

When we talk about robotaxis or fully autonomous vehicles, we’re talking about SAE Level 4 or SAE Level 5. Tesla’s so-called “Full Self-Driving,” or FSD, software is an SAE Level 2 system, only offering advanced driver assistance.

In fairness, Tesla’s failure to deliver is not unique; Waymo (GOOG, GOOGL), Cruise (GM), Zoox (AMZN), Mobileye (INTC), and every other company working on self-driving cars has, so far, failed. What is unique to Tesla, and uniquely deserving of criticism, is Tesla’s decision to charge customers for a feature called “Full Self-Driving” (which is not full self-driving). Tesla’s CEO Elon Musk is also the worst offender in terms of confidently predicting, again and again, that full autonomy is right around the corner.

Moravec’s Paradox

The situation with autonomous cars feels strange, given the recent ascendancy of Large Language Models (LLMs) such as OpenAI’s GPT-4 and Google DeepMind’s Gemini. The root of the problem is what’s known as Moravec’s paradox. A toddler’s motor skills are the envy of any roboticist, while current LLMs can prove mathematical theorems. As a rule of thumb, what’s easy for humans is hard for AI, and vice versa. We have AI that can write software, but we’re very far away from having AI that can unload a dishwasher.

As far as self-driving car companies go, Tesla still seems best-positioned, given the training data it can collect from its massive fleet of production cars. However, this doesn’t mean much, as the problem of fully autonomous driving appears intractable given the current state of deep learning science. One open research problem that seems relevant to self-driving cars is video prediction, i.e., the ability to predict future video frames from past video frames. Toddlers, again, excel at predicting what will happen next in their visual world, while machines suck.

Drop a ball in front of a two-year-old and if the ball somehow floats to the ceiling, the two-year-old will be surprised. From a very young age, humans develop a complex model of the world and its dynamics. For AI, this remains an elusive goal. A self-driving car doesn’t have a complex world model.

End-to-End Learning

The most recent pivot in Tesla’s technical strategy toward self-driving is to end-to-end learning. Under this approach, there is a direct input-output relation between the sensors (e.g., cameras) and the actuators (e.g., steering wheel), with one big neural network in between them.

End-to-end learning is a very old idea. One criticism of it is that since it’s all just one big neural network, you can’t test the accuracy or performance of sub-components of your system. One could just as easily interpret Tesla’s pivot to end-to-end learning as a desperate Hail Mary as a brilliant flash of insight.

Optimus

What about Tesla’s other foray into AI-powered machines, the humanoid robot prototype known as Optimus? In this case, Tesla’s engineers are trying to solve what is probably a much harder problem with much fewer resources, including, crucially, training data. My hopes for Optimus are, therefore, even dimmer than my hopes for “Full Self-Driving.”

To clarify, Optimus may prove usable for some narrow tasks like tightening screws in a Tesla factory, but the dream of a general-purpose humanoid robot seems very far away indeed.

Valuation

How much of Tesla’s $0.76 trillion valuation is owed to dreams of a robotaxi future? This is a fiendishly difficult question to answer. With perhaps the sole exception of ARK Invest, analyst firms tend not to price anything in (or a very small amount) for robotaxis in their explicit valuation models.

If I had to guess, I would wager less than 10% ($76.4 billion) of Tesla’s valuation is attributable to the expected value of robotaxis. I would also guess the number is closer to 1% ($7.64 billion) than 10%. However, these guesses are very low-confidence.

So, how much should this whole discussion matter to investors? Probably not very much, unless you happened to be pricing in a lot for robotaxis in your valuation model.

The Very Long Term

In the very long-term future, by which I mean at least five years from now and probably more than ten, there will be robotaxis. For an investor today, however, it doesn’t make sense to invest in Tesla, Inc. or any other company based on the robotaxi premise. From a financial point of view, eventually might as well be never.

Lately, the success of LLMs like GPT-4 has spurred many people into talking seriously about artificial general intelligence (AGI), a hypothetical general-purpose form of AI that can think, reason, understand, plan, and act just as a human can. The pseudo-prediction market Metaculus has a median prediction of 2032 for the first creation of an AGI. Shane Legg, a Co-Founder of DeepMind (now Google DeepMind), predicts a 50% chance of AGI by 2028. Holden Karnofsky, the Director of AI Strategy for the multi-billion-dollar foundation Open Philanthropy, predicts a 10% chance of AGI by 2036. Such predictions are, of course, highly speculative and highly controversial.

SAE Level 5 driving may turn out to be an AGI-level problem or close to it. In that case, it will be very difficult for investors to predict when, or if, it will arrive.

Analyst’s Disclosure: I/we have no stock, option or similar derivative position in any of the companies mentioned, and no plans to initiate any such positions within the next 72 hours. I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it (other than from Seeking Alpha). I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.

Seeking Alpha’s Disclosure: Past performance is no guarantee of future results. No recommendation or advice is being given as to whether any investment is suitable for a particular investor. Any views or opinions expressed above may not reflect those of Seeking Alpha as a whole. Seeking Alpha is not a licensed securities dealer, broker or US investment adviser or investment bank. Our analysts are third party authors that include both professional investors and individual investors who may not be licensed or certified by any institute or regulatory body.