Summary:

- Roku’s financials and business metrics do not fully reflect the business, causing a disconnect that might confuse investors.

- Most of Roku’s advertising seems to be brand vs. programmatic, impacting the growth of its platform business.

- Walmart’s acquisition of Vizio is unlikely to pass regulatory scrutiny, given harm to competitors is easily demonstrable.

Marvin Samuel Tolentino Pineda

Last time I covered Roku Inc. (NASDAQ:ROKU) was in January 2023. Back then, I said that the company’s move to manufacture its own-branded TVs would improve margins and revenues, mainly because Roku does not receive license revenue for offering its OS to other TV OEMs.

The stock has gone on to gain 33.6% since then, matching the S&P 500 during the period. However, it is down almost a third YTD and more than 35% since I initiated coverage in mid-2022. In that initial article, I argued that the large size of the TV market and Roku’s dominant position in it could help the company become a giant.

Since then, a lot has happened in terms of management execution and the business model of its platform business that I think it deserved a follow-up. This article will break down what Roku’s business model really is. It will also highlight two challenges facing the company, the progress management is making in tackling those challenges, and what that means for the stock going forward.

Roku’s Competitive Advantage: An Operating System Made for The TV

Roku’s main competitive edge is that its operating systems were designed with TV hardware in mind. Competing TV OS relied on smartphone operating systems, which use much more expensive chips. Roku’s OS, meanwhile, is optimized for the limited hardware of TVs. Such an advantage could come in handy when chips prices soar thanks to generative AI. Here is the company highlighting that advantage in the 2022 annual report:

The Roku OS is designed to run on low-cost hardware which enables us and our licensed Roku TV partners to sell streaming players and TVs at affordable prices. Consumers connect their Roku streaming devices to our streaming platform via a broadband network and are able to access a wide selection of content through a streaming experience that is both delightful and easy to use.

I’m unsure of the durability of this competitive advantage. Surely, big tech has the capability to replicate it, yet they have yet to do so. The good news, however, is that Roku has a first-mover advantage also. Because let’s say big tech manages to replicate the OS cost advantage, the 80 million households using Roku are likely to stick with it if they are satisfied with the product.

Those two advantages should be looked upon favorably by investors. However, Roku’s platform segment is where the real challenges lie, I’ve labelled them the accounting challenge and the monetization challenge.

Roku’s Accounting Challenge: The Disconnect Between Costs And Revenues

Roku is two businesses in one. It’s important to look at them separately, yet it’s almost impossible to do so. I’m not referring to the player and platform segments, but rather that Roku sells the OS to end consumers and the advertising to advertisers. It then presents metrics attributed to the end consumers and is supposed to be measured based on them.

Let’s take the latest quarterly results as an example. Here is an excerpt from Seeking Alpha’s reporting on the company’s earnings:

Roku stock tumbled 21% out of Friday’s market open, its biggest intraday move since 2022, and the stock found its lowest point since November after what appeared to be a solid fourth-quarter earnings beat.

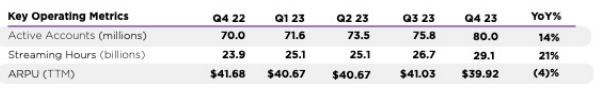

The story appeared to be that Roku beat expectations and issued strong guidance for the first quarter, but that the company didn’t beat by as much as investors hoped. And attention naturally fell on the company’s average revenue per user figure, which dipped 4% (but amid active account growth of 14% to 80M).

Wall St. and Roku’s management give much attention to ARPU. However, in my opinion, it is a distraction. It serves little purpose in informing an investor about the state of the business. Roku’s customer acquisition and monetization are two completely separate businesses.

Roku’s ARPU is a misleading figure (Company filling)

For instance, Roku’s ARPU of $39.92 per account (derived by dividing the TTM platform revenue of $2.994 billion by the average active accounts of 75 million.) completely overlooks that Roku hasn’t monetized international accounts yet as it is yet to start striking deals with advertisers. The decline in ARPU is merely a reflection of Roku’s international expansion, rather than a deterioration in the lifetime value of its customers.

This is true on the cost side as well. Marketing costs for the year were just a bit more than $1 billion. That would put the acquisition cost of the 10 million customers acquired during the year at a $100 a customer. Meaning the company spends $100 a year to acquire customers that pay them $40 a year or so with quite low gross margins as well. The reality, however, is that Roku spent $35 million of that $1 billion on advertising to acquire new accounts, according to the notes in the 2023 annual report. The rest of the $1 billion was spent on its sales force to mainly strike advertising deals, among other things. So, the acquisition cost is closer to $3.5 per account than it is to $100. That is a wildly different outcome, on the cost side alone, than one would reach by relying on headline numbers.

Roku’s financial reporting is similar to that of Netflix (NFLX) (expected given the history both companies share with Roku being a Netflix unit), but the comparison is misleading in my opinion. Unlike subscription-driven businesses where revenue scales with customer growth, Roku’s revenue generation is subject to a lag, particularly in brand advertising. That difference means that investors must not submit to statistical metrics and try to understand the nuances behind them.

There is a counter argument which would say that Roku doesn’t present its business that much differently than Meta (META) and that too is an advertising business, and it focuses on ARPU like Roku does.

My response is that this focus has, as well, led to confusion about the company’s monetization in 2022. I discussed this particular issue with Meta’s monetization in Sep. 2022 when the stock was at $148 a share:

An important thing to note here is that growing Reels is a drag on Meta’s own revenue, because Reels currently doesn’t monetize as well as Feed or Stories. So while the decline in revenue can be viewed as the emerging competitive threat of TikTok, it can actually be the exact opposite; Meta is growing its competing product so well that it is taking ads away from Feed and Stories. Given Reels is growing faster than Stories did at identical times post-launch, and it will eventually monetize as well as Feed, the company could be back to 20% sales growth faster than many bears think. So this could be very bullish news for the stock.

It’s possible Roku is facing a similar dynamic; its growth internationally is a current headwind to ARPU now but could lead to higher revenue growth down the line as they start monetizing those users.

There isn’t really a way to repurpose the metrics currently in use or try to restate Roku’s financials to get a more accurate picture of the company’s financial performance. Investors simply have to work on understanding the nuances of the numbers. And even with that effort, there is no guarantee of getting a clearer picture.

And while Roku’s accounting challenges may hint at a possibly exciting future for the company, its monetization challenges are much more serious.

Roku Has A Structural Monetization Challenge: Streaming Giants Are More Powerful

Roku has big monetization question marks, resulting primarily from lacking market power and its advertising strategy. The lack of market power was clearly on display during its dispute with YouTube, the company revealed that “Roku does not earn a single dollar from YouTube’s ad supported video sharing service today, whereas Google makes hundreds of millions of dollars from the YouTube app on Roku.”

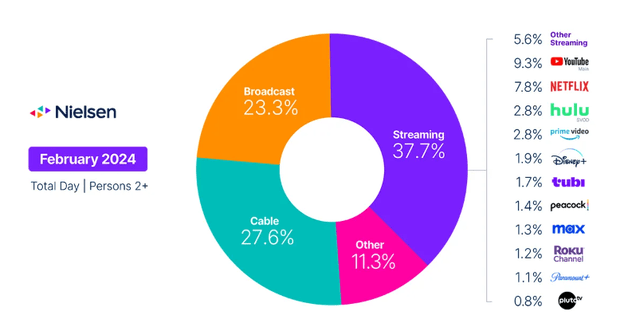

This is a real problem given YouTube is the most popular streaming app in the US, and highlights the gap in the ability of distribution platforms and content companies in generating revenues. It shows that the content companies are the more valuable part of the value chain.

YouTube is roughly a 10th of streaming viewing time, but is not monetized on Roku (Nielsen)

This means Roku could have a structural monetization issue; it is simply weaker against content companies compared to cable in the past. Unlike cable, Roku’s switching costs are much lower. If a streaming giant like YouTube were to take its app off Roku, all consumers have to do is get another streaming stick delivered. This ultimately means Roku has little leverage against content companies, particularly the scaled players.

And speaking of streaming sticks, Roku doesn’t make any money off of licensing its OS to TV OEMs, similar to Google’s android model. The company acknowledges that in its annual reports’ risk factors, saying “our Roku TV licensing program has been expanded to certain international markets and has represented an increased share of new Active Accounts. We do not typically receive, nor do we typically expect to receive, license revenue from these arrangements, but we typically incur operating expenses in connection with establishing and supporting these commercial agreements. The primary economic benefits that we derive from these license arrangements have been and will likely continue to be indirect, primarily from growing our Active Accounts.”

Numbers back that up as well. If you look at the average selling price for Roku hardware (device sales divided by accounts added), it has consistently been in the $30-$50 range per account. It’s why I think the company’s move to design and sell its own Roku-branded TVs could boost revenues and margin.

How Roku Makes its Money, and Why it’s Hindering the Stock Price

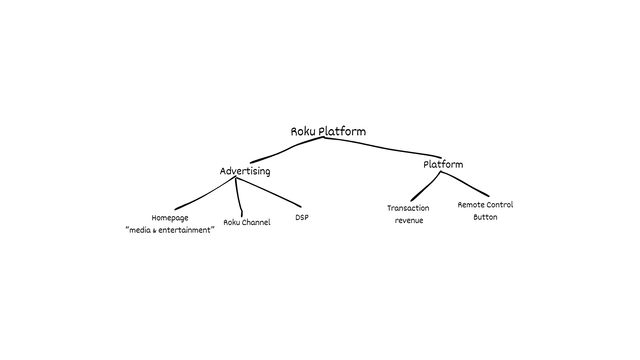

Roku has diverse revenue sources, but almost everyone of them is challenged (Created by author)

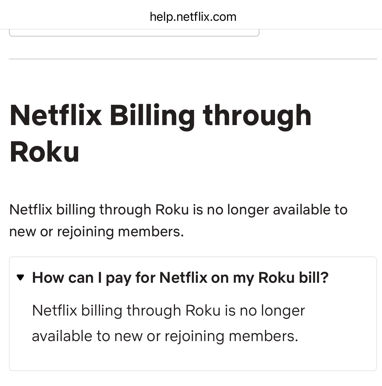

We’ve touched a bit on the platform’s business model earlier, particularly how Roku doesn’t make transaction revenue from YouTube or YouTube premium. Transaction revenue can come in the form of a revenue share from the subscriber Roku helped sign from a particular service. Another form of revenue is Roku Pay transaction fees, money the company earns when its customers use its payment platform to pay for subscriptions. That particular business is also facing problems from Netflix, as we can see in the image below:

Netflix No Longer Uses Roku’s Payment Platform (Netflix)

So Roku is facing difficulty monetizing its platform with both YouTube and Netflix, the two biggest streaming services in the US which accounted for 16.8% of viewing time in the US in February 2024 according to Nielsen. This underscores Roku’s lack of market power compared with traditional cable providers. Rather than earning transaction revenue from streaming giants, Roku is more of a marketing tool for subscale streaming services, earning fees for its role in customer acquisition and retention.

This problem carries over into its advertising service as well. Roku doesn’t break out advertising revenue by source, but Needham’s Laura Martin has a useful estimate noting that a third of advertising is coming from the homepage, a third is coming from the Roku Channel, and a third is coming from OneView, its demand side platform. She mentioned this estimate in her conversation with former Roku CFO Steve Louden. The whole talk is worth a read.

Starting with the homepage, the dominance of brand advertising over programmatic advertising in this part of the business serves as a drag on revenue, given brand advertising requires a dedicated sales force and often yields lower margins. This explains to me why The Trade Desk Inc. (TTD) has gone on to become 4x Roku in market cap despite having less revenue, and despite the two having the same market cap circa 2019. TTD spends 23% of its revenue on marketing, compared to the 30% Roku spends on the line item. And as highlighted earlier, only $36 million of that (equivalent to 1% of revenue) is on advertising its TVs, so the majority of the spend is on ad sales. A significant portion of Roku’s advertising business is dedicated to streaming services to market their shows, rather than to all kinds of advertisers. Roku might as well be considered a SaaS marketing tool for streaming services. And with entertainment companies struggling, no wonder Roku would struggle as well.

The lack of programmatic ads can clearly be seen when reading management’s letters to shareholders or the annual report.

Roku City is example of brand advertising rather than programmatic (Company filings)

Roku City is an example of the company’s focus on brand advertising. In the Q4 letter to shareholders, Roku said: “Since opening Roku City (our beloved screensaver) to brand advertisers, we have executed integrations with some of the world’s most renowned brands, including Coca-Cola, Disney, Lego, McDonald’s, Barbie/Mattel, Carnival, Acura, and more. Roku City integrations have reached an average of more than 40 million Active Accounts. These engaging executions — again, only available on and through Roku — drive positive brand awareness for marketing partners, delight viewers, and elevate Roku’s distinct and playful brand attributes. “

So as clearly mentioned in the paragraph, this is brand advertising. This isn’t a case where advertisers log in to a platform, target their audience, and the ad is shown to relevant customers. These are deals negotiated with the companies, requiring meetings and a dedicated sales force that is simply more timely and costly to implement. Roku City is part of that homepage advertising, which represents a third of advertising revenue, according to Needham. Roku refers to the homepage advertising as the media & entertainment promotional spend.

And as highlighted in the annual report and the letter to shareholders, this segment is facing tough headwinds. With streaming services looking to rationalize spend, less of them are looking to spend on marketing losing streaming services. This has been evident in the decline of marketing costs in WBD and Disney, among other streaming services.

Management has also acknowledged that more work needs to be done to improve homepage advertising, here is Louden at the Needham Technology & Media Conference almost a year ago:

In terms of the home screen, yes, you’re right, what we call our media and entertainment business. That’s effectively promotional spend by the content services on the platform. You’re right, it is currently a display ad… there is a lot of work to be done on that. Increasingly, those display ads can be personalized, right, on that home screen and as well as the fact that we are increasingly selling them not on a CPM basis, but rather on a performance basis.

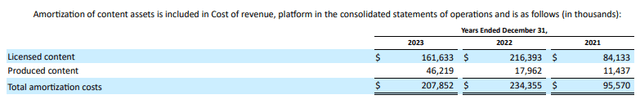

The second major segment contributing to Roku’s advertising revenue is the Roku Channel, this is the more stable of the company’s advertising businesses. Despite management not providing specific financial results, management mentioned in previous earnings calls that engagement was up 50% in 2023 and 80% in 2022. The annual report had a useful table that’s relevant to the cost of running the Roku Channel:

The Roku Channel is likely seeing gross margin expansion (company filing)

It is encouraging to see content amortization decline in 2023 while engagement was up 50%. Obviously, this doesn’t mean that revenue from the Roku channel has grown 50%, but there should be a correlation nonetheless. Page 57 of the annual report said subscriptions on the Roku channel was strong in 2023, and that the weakness in advertising for the year was driven by the homepage. This all in all suggests margins for the Roku Channel grew in 2023. All of the content amortization expense is for the Roku Channel, making it a good proxy for the channel’s expenses.

This brings us to Roku’s Demand Side Platform OneView, which sells the Roku Channel’s ad inventory along with all the other remaining ad inventory the company has.

Roku bought Dataxu in 2019 for $150 million, before relaunching it as OneView in 2020. Initially, Dataxu accessed Amazon‘s Fire TV ad inventory. This probably made the deal even more attractive because it would have made Roku a must for advertisers looking to allocate marketing budgets to streaming. Amazon swiftly dropped Dataxu though post its Roku merger, which probably undermined the success of the platform.

OneView operates as a way to programmatically buy all types of ads on Roku, including the Roku Channel’s ad inventory along with other ad inventory. The decline in advertising in 2022 led to Roku ultimately opening up its ad inventory to other DSPs to boost demand. This undermines the thesis that Roku can command the streaming space and become a giant OS for the TV. Giants that commanded other verticals like Meta and Google exclusively sell their ad inventory through their own DSPs. And remember how Amazon was opening up its Fire TV inventory to third-party DSPs? They phased them out and now only Amazon’s DSP can be used to buy its inventory.

However, there’s a more positive explanation: Roku management highlights that only 25% of ad budgets are allocated to streaming, despite streaming comprising over 50% of viewing time. This gap could potentially be closed as ad budgets follow viewing and Roku would emerge as a big winner. I’m skeptical this is the explanation, given The Trade Desk management touts CTV growth at a time Roku is struggling to hit mid-teens growth. Vizio also saw its competing platform grow revenues in the mid 30s percentage points in Q4 of 2023, albeit off of a much smaller base.

Having said that, I continue to rate Roku a buy. Almost all the risks are priced-in at this moment given the market cap. The company’s high liquidity and the fact it turned free cash flow positive means it’s worth sticking with it to see how management address their monetization issues in my view.

Roku’s Technicals Are Bearish

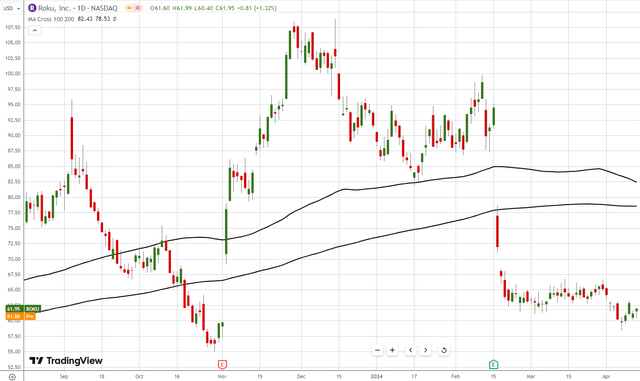

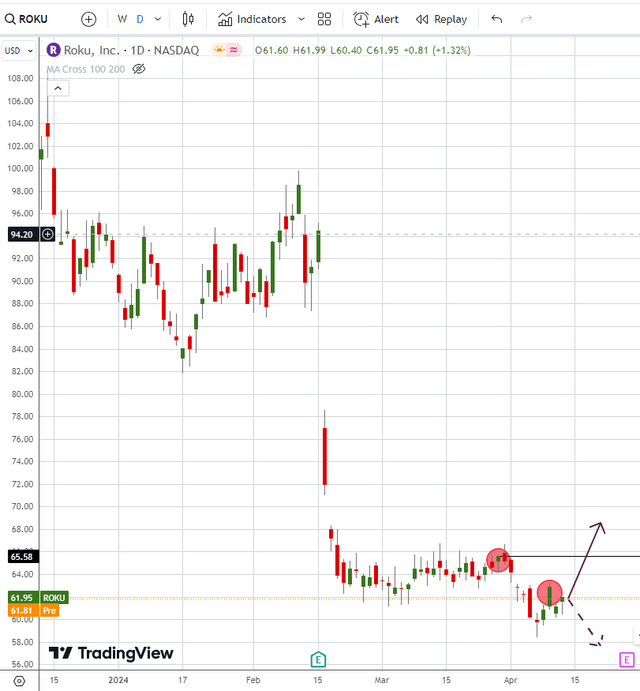

100, 200 MA point to a bearish trend (Tradingview)

Roku’s stock price fell sharply below the 100 & 200 moving averages after Q4 earnings. It continues to trade well below both averages, leaving no doubt the trend is bearish. The 100 MA is still above the 200 MA, so there’s a silver lining, if you will. The most immediate low was reached April 5 at $58.4 per share, the previous one was on Oct. 30 of the previous year and stood at $55.02. Those two levels are likely where the next support levels would be.

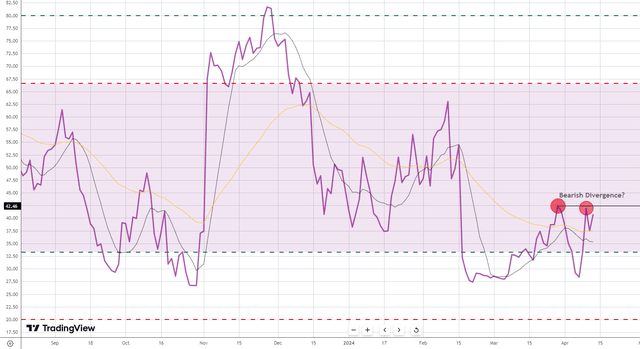

RSI points to a new low for Roku’s stock price? (tradingview)

I firstly want to point out that I interpret the RSI based on John Hayden’s book and Andrew Caldwell’s work. It is a little different than the conventional wisdom, but I found it more effective.

We can see That Roku’s trend turned bearish on the RSI after Q4 earnings results. It violated the 33 support on the RSI and has spent much of its time below that level since then.

I also want to point out a potential bearish divergence in the making, they are the two red dots in the image. The RSI reached a high of 42.46 (which corresponded with a closing of $65.58 a share on the chart), pulled back, then moved up 41.89 days later. The price closed that day at $62.85 a share. If the RSI was to close above 42.46 without the price closing above $65.58, that might suggest a future lower low, according to Caldwell’s work. It basically suggests that despite stronger levels of buying according to the RSI, bulls were not able to push the price to a higher high, and it could indicate exhaustion and an imminent lower low. The price target in this case according to Caldwell is the difference between the high ($65.58) and whichever closing price violates the RSI without breaking the $65.58 level, subtracted from the closing below between them, which was $59.83. I’ll provide an update in the comments section if the divergence does materialize.

RSI hints Roku stock price could be at a crossroads (tradingview)

The two circles marked on this chart correspond to the RSI readings I showed before. If the RSI was to close above 42.46 without the price closing above $65.58, then there is a higher possibility the stock will close below the most-recent lowest close of $59.83 a share.

A Word on Walmart’s Acquisition of Vizio

I will not dedicate too much time to this topic, but I think Wall St. is way too confident this deal will close. I wrote a host of articles on the Activision and the iRobot deals over the past two years, I recommend revisiting those articles as they are very relevant to the Walmart-Vizio deal.

Essentially, this deal is a vertical merger. One of the first things regulators will look at it is whether this deal would lessen competitions and harm other players in the market. Harm to Roku and others is quite obvious, and more importantly it is easily demonstrable as well in my opinion. The fact Walmart’s press release didn’t mention a timeframe for closing the deal in my opinion suggests uncertainty of when this deal could pass regulatory scrutiny.

The more lasting impact of the deal will probably be on the valuation of Roku. Wells Fargo cut Roku’s rating, saying that Roku’s story needs to improve for investors to continue pricing it at a premium to Vizio. But the premium is in the eye of the beholder, as I don’t see any premium awarded to Roku, here’s why. Walmart seems to be interested in VIZIO’s TV OS. In the deal’s press release, Walmart’s Chief Revenue Officer Seth Dallaire said “We believe VIZIO’s customer-centric operating system provides great viewing experiences at attractive price points. We also believe it enables a profitable advertising business that is rapidly scaling.”

At 18.5 million monthly active users for its platform revenue, Walmart is buying Vizio at $124 per active user. Applying that to Roku, we’d get a market cap of almost $10 billion, a 10% premium to Roku’s current price. This tells me Roku is not trading at a premium to Vizio if you focus on Vizio’s platform business, which seems to be Walmart’s rationale for the deal.

Conclusion

Despite having a cost advantage in the TV market, Roku has real problems in monetizing its user base. A big chunk of its advertising is done through a direct sales force which is more expensive, it also relies more on brand advertising rather than the more lucrative programmatic advertising. The advertising business also seems more geared towards entertainment companies, making its platform more akin to Etsy than Shopify. Roku would probably need to rework its ad strategy to make its product accessible to as wide a range of advertisers as possible. Roku also lacks market power against the big streaming companies such as YouTube and Netflix, rendering it unable to monetize their viewing time. The fact that it opened some of its ad inventory to third-party DSPs could be a warning sign it could never be a scaled player in the ad market, given none of the major tech giants that sell ads like Meta, Google, and Amazon use third-party DSPs to clear their inventory. But it might just be that streaming still hasn’t matured yet and so hasn’t attracted the ad dollars its viewing commands. The Walmart-Vizio deal put a lot of pressure on the stock earlier in the year, but this deal seems unlikely to close given the harm to competition will be easily demonstrable. All in all, I maintained my buy rating on the stock, but mainly because its current market cap already reflects pessimism in the company’s ability to improve its monetization.

Analyst’s Disclosure: I/we have no stock, option or similar derivative position in any of the companies mentioned, and no plans to initiate any such positions within the next 72 hours. I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it (other than from Seeking Alpha). I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.

Seeking Alpha’s Disclosure: Past performance is no guarantee of future results. No recommendation or advice is being given as to whether any investment is suitable for a particular investor. Any views or opinions expressed above may not reflect those of Seeking Alpha as a whole. Seeking Alpha is not a licensed securities dealer, broker or US investment adviser or investment bank. Our analysts are third party authors that include both professional investors and individual investors who may not be licensed or certified by any institute or regulatory body.