Summary:

- With a P/E near 200, Snowflake is more than just a value investing nightmare… that P/E is even way above what that of Nvidia.

- I tend to accept high valuations for shares of companies with super prospects, but even I can’t make the numbers here work.

- Still, I’m rating SNOW as a “Buy.”.

- Maybe I’m crazy, or maybe there’s more to the story.

- There is… a lot more: I’m coming at this similar to the way William Miller, a famous and long-standing Amazon.com bull (who turned out to have been right), initially thought about that stock.

loops7/E+ via Getty Images

Am I crazy?

I’m going to say “Buy” for shares of data-company Snowflake (NYSE: SNOW).

The stock’s P/E FWD is near 200. Even Nvidia (NVDA), the Wall Street face of AI hype, isn’t that expensive. The latter’s P/E is a mere 49.

You can judge my sanity.

But before I defend myself, let me start by at least saying I’m not ignorant. I admit that by any numerical valuation metric, the stock looks badly overpriced.

The company is one of today’s big-name tech-growth companies. And as with many others, AI is relevant. SNOW is into data… big, big, big, big data.

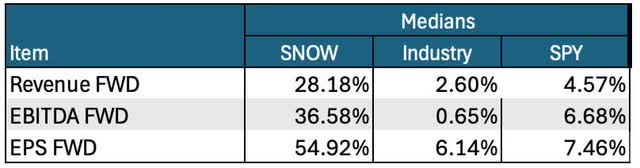

Readers familiar with my work know I’ll accept a very high ratio if the Proj. 3-5Y EPS Gr figure is also high. For SNOW, the consensus growth rate projection is 23.31%. That’s terrific. But it’s not terrific enough. The PEG FWD is 8.8.

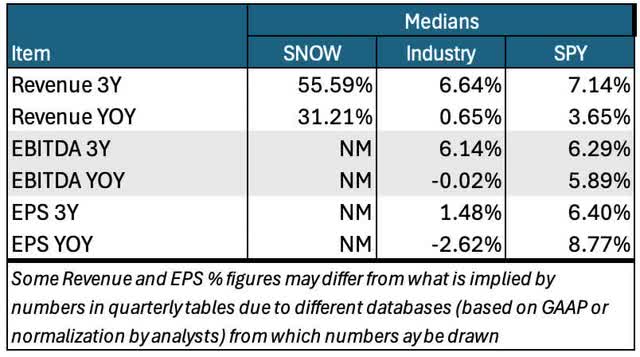

I’m skipping my usual tabular value presentation. (I typically compare SNOW to medians for the SPDR S&P 500 ETF (SPY) and the industry, in this case it would be Internet Services and Infrastructure.

You don’t need all that to roll your eyes at a P/E near 200. You know it’s stratospheric.

Now, suppose this emerging growth company was just barely breaking into the black. Maybe it’s EPS amounts to pennies per share.

Suppose the forward estimate of EPS is only $0.03 per share. Perhaps it was negative $.85 a year earlier. And suppose the Street expects $1.20 in the next year. If it were anything like that, a 200 PE FWD might not faze me.

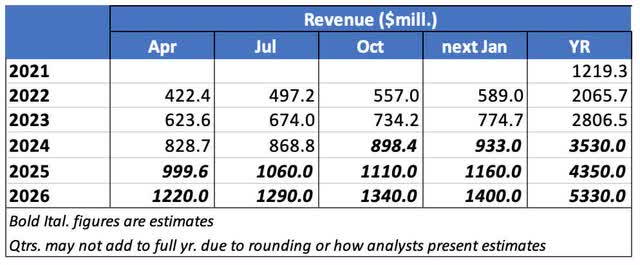

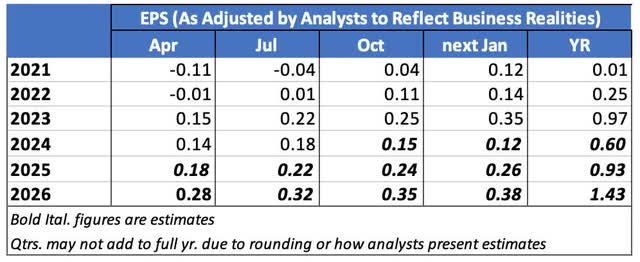

But that’s not SNOW. Here are its quarterly trends.

Analyst Compilation based on Data from Seeking Alpha Earnings and Financials Presentations Analyst Compilation based on Data from Seeking Alpha Earnings and Financials Presentations

Perhaps a strong combination of growth and EBITDA Margin could support a high EV/Sales ratio. This is a good metric for emerging companies that don’t yet have normal profits.

SNOW’s EV/Sales (FWRD) ratio is 11.75. That, too, is very high. NVDA’s ratio is 26.31. So perhaps there’s hope for SNOW.

Actually, this idea fails.

SNOW’s EBITDA margin is -35.25%. (Are you wondering about a negative margin and positive EPS? That table shows normalized. EPS. But GAAP EPS in the red. I’ll discuss below.) NVDA’s EBITDA margin is 63.53%!

And by the way, a negative EBITDA (sometimes called Operating) Margin can be a red flag in and of itself.

I understand that very young companies can need time to outgrow relatively fixed overhead. When they do, the margin will turn positive.

But until they do, I typically adopt a prove-it wait-and-see stance. I tend to analogize such companies to adult kids who haven’t yet moved away from their parents’ basements.

It takes a lot to get me interested in a basement dweller. Here, however…

William Miller’s AMZN Experience Inspires the Framework Through Which I’ll Rate SNOW as a “Buy”

Miller is a well-known value-oriented investor. Yet he owned Amazon.com (AMZN) in 1999. (Actually, he bought through the 1997 IPO, sold it, regretted having done so, and then repurchased in 1999.)

He may well be the most famous long-term AMZN bull. He experienced many angst-producing ups and downs. Ultimately, Miller succeeded. (See my 7/13/24 AMZN post for a sense of how successful long-term AMZN holdings fared.)

Miller’s bold moves attract interesting interviews. He’s very bullish on Bitcoin now. I won’t comment since I’m clueless about all things crypto.

Regarding company stocks, Miller typically recites the standard quant lingo. He discusses companies’ potential to earn long-term returns that outstrip the cost of capital. And I expect he likely has spreadsheet models like that.

But I think such models are inherently non-credible for truly emerging businesses. I explain this view in my 5/28/24 NVDA writeup.

I won’t try to read Miller’s mind. So, I don’t know if he privately agrees. But some quotes suggest such modeling may not be the be all and end all for his AMZN-like choices.

Whether that’s so or not, we can still look to Miller’s approach to AMZN. That will set a context for the non-traditional way I’ll assess SNOW.

In 2015, Motley Fool wrote as follows regarding Miller’s AMZN investment:

Miller isn’t afraid to throw valuation metrics aside. He pointed out that Amazon may not have looked attractive based on traditional measures (price-to-earnings, price-to-book, etc.), but “that speaks more to the weakness of those methods than to the fundamental risk- reward relationships of those businesses.” Essentially, traditional measures only work with traditional companies. So, when a disruptive Internet company like Amazon arrives, you end up with its growth potential being compared to brick-and-mortar book stores. This was a clear misunderstanding of what Amazon could be, and that led many investors to view Amazon as overvalued.

In 2019, Institutional Investor wrote as follows about an interview with Miller:

Many value investors use accounting-based techniques to determine valuations.

“But that’s very dangerous, because [generally accepted accounting principles] are designed to capture the underlying economics of a business that’s consistent across all industries,” Miller argues. “That language changes slowly.”

It also means that GAAP-based research often doesn’t measure businesses well, he says.

“People missed Amazon because they said it doesn’t make money,” he explains. “GAAP isn’t divinely inspired.” Miller doesn’t ignore GAAP- based numbers — but he views them simply as inputs to figure out the true value of a business.

The longtime money manager thinks he also benefits from an analytical advantage. “I didn’t have my own information on Amazon. My view was just that people were looking at it incorrectly.”

Miller partly credits behavioral analysis for his success. “Social psychologists have shown how groups of people behave, weighing dramatic information more than non-dramatic, being too short-term- oriented, etc.,” he says. “We try to exploit all those things.”

On August 26, 2004, Forbes wrote thusly about its interview of Miller:

I’d gotten to know Jeff Bezos a little bit and I was very impressed with the way that they thought about the business and what they were doing…. It was a retailer, but Amazon didn’t have stores. They had warehouses and shipped direct to the customer. That was Dell’s model. Amazon’s metrics didn’t look anything like Walmart or Home Depot. They were exactly like Dell—same operating margins, same gross margins, same low-cost overhead, same high inventory turnovers.

I hope a picture of how I’ll be approaching SNOW is starting to come into focus. Numbers will help. But they won’t dominate.

How SNOW Got Going

Today, we take the cloud for granted. But in 2015, Peter Wagner, founding partner Wing (a venture capital firm that backed SNOW early on), asked a panel of IT execs when data analytics would move to the cloud. Their answer: “Uh, never.”

That was consistent with how Oracle (ORCL) co-founder Larry Ellison saw the world. My 10/11/14 article on Broadcom (AVGO) quoted his now famous anti-cloud rant. “It’s complete gibberish. It’s insane. When is this idiocy going to stop?”

Who could doubt Ellison? After all, on-premises enterprise-scale relational databases ruled.

The relational element is what makes big data click. Simply (very simply) put, imagine a customer data set and also, a purchase order data set.

The company needs to track both. It would be unwieldy to put everything in one giant data table. So, they’re kept separate.

But one piece of information is common to both tables… a Customer ID. This “key” lets the tables “relate” to one another.

That makes it easy for the company to track customer behavior, customer accounts, inventory, and product popularity as a whole and based on region and customer demographics.

There’s a huge legion of data analysts, database administrators and SQL programers that keep this stuff running.

But not long after the IT panel scoffed to Wagner about the cloud, enterprises stepped up efforts to move data there. We now understand why…

Data work was freed from specific locations. And companies found it better to pay cloud services to worry about servers, maintenance, updates, etc. It really helped that the cloud learned to handle security and privacy.

But Oracle wasn’t leading the way. Industry observers wondered if (premises bound) relational databases would die out.

Eventually open-source outfits like Apache and Hadoop became the rage. Analytics became the new big thing.

Meanwhile, Benoit Dageville, Thierry Cruanes, two veteran Oracle architects who saw the cloud-future decided to leave. They, together with Marcin Żukowski, a data warehousing expert who had startup experience, formed Snowflake in 2012.

Early on, many wondered if the newcomer would be crushed by AMZN. Snowflake built its offering on top of AWS. But Amazon introduced its own cloud warehouse, Redshift.

Skipping all the gory details, Snowflake survived, and then some…

SNOW’s Modern Approach to Data

Unlike Redshift and others, SNOW’s offering was built from scratch for (native to) the cloud. It wasn’t and isn’t shackled by an old on-premises heritage.

SNOW was able to, and did, make it easier for users to implement and manage their clouds.

And they can do so where they want. They’re not captive to AWS or any other hyperscaler. (SNOW is the database. Someone else, like AWS, runs the cloud that houses and serves it.)

SNOW separates data compute from data storage. This may not seem crucial to ordinary folks. But it’s huge for data pros.

Each can be managed and maintained with full flexibility. Actions done within one don’t burden, or slow, the other. Faults in one are corrected without impacting the other.

And users pay only for what they actually use. They don’t pay for idle resources.

This means SNOW’s revenues are based on usage. It doesn’t have the recurring subscription revenue streams many crave. But for SNOW, it makes sense given likely growth.

Today, more than 90% of businesses use the cloud. But not all are all in. Only 60% of data is stored there.

Day-to-day computation has a long growth runway.

“Big data” (data sets too large for conventional software) is opening up more analytic possibilities for more users.

So, too, is unstructured data that doesn’t fit normal row-column format. Examples include graphics, text documents, handwritten notes, and videos.

And, of course, there’s AI. That’s still in the early stage of being developed.

It would seem impossible to set subscription rates that wouldn’t wind up undercharging or overcharging different users at different times.

And more data is collected every day. So even without new uses, volume alone is mushrooming.

Usage-based revenues let SNOW grow along with the new digital world. That’s the sort of potential that makes a long-term growth case for the company.

And by building from scratch, SNOW is able to let its clients escape the confines of silos.

These are data repositories built and secured by and for a particular user group.

An example would be a separate database for sales, human resources, and product. Someone evaluating salesperson performance may need to determine commission or bonuses. That would touch all three data repositories. But siloed data is often incompatible with data in other silos.

I don’t have the background to supply here a full course in data science. But I hope you can recognize the merits of cloud flexibility and scalability from built from scratch.

That’s far better than adapting from old, legacy, on-premises offerings. Don’t underestimate how much time and effort many data users, even today, spend squeezing round pegs into square holes. SNOW users need not do that.

SNOW is constantly adding new things.

It was originally into the data warehouse model. Those “store large amounts of current and historical data from various sources. They contain a range of data, from raw ingested data to highly curated, cleansed, filtered, and aggregated data.”

SNOW’s Iceberg offering helps users effectively manage data lakes. These “store large amounts of structured, semi-structured, and unstructured data….Data does not need to be transformed in order to be added… efficiently without upfront planning…. (This flexibility) enables business analysts and data scientists to look for unexpected patterns and insights.”

The company’s Cortex AI offering helps users build generative AI models.

SNOW is building specialized versions of its offering for specific industry verticals. It already has platforms for financial services, healthcare, retailers, tech, media, education, telecomm, and the public sector.

And the company’s Snowflake Marketplace offers a variety of third-party apps. These aren’t two-kids-in-a-garage type things. FactSet (FDS), a world class data vendor, is available through SNOW’s marketplace.

Competition, Especially from Databricks

SNOW isn’t alone in its business. Others offer cloud-based data warehousing and data lakes.

As noted above in connection with AMZN’s Redshift, there’s something to be said for SNOW’s independence. For the most part rivals need to be used in a particular platform.

The industry has evolved to the point where competitive analysis needs to focus mainly on Snowflake versus privately-owned Databricks. (I’m planning a separate article that will address Oracle (ORCL), the giant that sort-of spawned SNOW.)

Bare bones feature lists seem identical. SNOW and Databricks now compete head-to-head pretty much across the board.

But they evolved differently. And that gives each a distinct feel.

As discussed, SNOW has a relational database heritage. It added, and continues to add, heavy-duty analytics. (Cortex is an example.)

Databricks came from the opposite direction.

It was born from AMPLab. That was a University California at Berkeley big data analytics project. One such development was open-source analytics-engine Apache Spark.

The Apache Spark founders launched Databricks. The former became the heart of the latter.

I assume you see where this is going.

Snowflake started with data and built its way into analytics. Databricks started with analytics and built its way into data. And now the two face off in the competitive arena.

So, which is better? Which will win?

I doubt there’s a clear answer. And there may not be one for a long time, if ever.

One possibility is having two big gorillas dominate the business the way AWS and Microsoft (MSFT) Azure do in cloud. The market seems big enough for both. As recently as 2022, Gartner estimated that only 30% of workloads (distinct from data) have gone cloud.

Future M&A is possible. (There are no rumors. It’s just me imagining.)

If I’m still writing when (or if) Databricks goes public, I’ll probably write about it too. And I may recommend owning both shares… like a data-leaders portfolio.

My research thus far finds little in the way of commentators or experts willing to pick one winner.

Many seem to favor both (or all) of the above. Some suggest that SNOW is for database geeks, while Databricks is for analytics nerds. But few seem willing to really pound the table for one as opposed to the other.

One exception I found is Harry Glaser. He’s co-founder and CEO a firm that “makes infrastructure for experienced ML teams to deploy large, complex models into their products very quickly.”

His 8/17/24 blog notes SNOW’s cloud-native heritage and its more modern database. Glaser ends by writing, “Databricks has strengths. But if offered a choice, I’d take a share of Snowflake every time.”

SNOW’s Numbers

See above for tables depicting the quarterly Sales and EPS trends

The NM (No Meaningful figure) designations in the historical growth table below should come as no surprise. Negative numbers will do that when computing growth rates.

Analyst’s computations and summary from data displayed in Seeking Alpha Portfolios

The forward growth table should likewise come as no surprise considering the above discussion.

Analyst’s computations and summary from data displayed in Seeking Alpha Portfolios

Returns on equity and assets, which I usually show, are not meaningful here.

The most important fundamental to mention is debt. It’s very modest. For SNOW, it amounts to just 2.31 times free cash flow. Industry and SPY medians are 6.35 and 7.85 respectively.

So, all things, considered I think the world has bigger fish to fry than fretting over SNOW’s $2 billion convertible notes placement last month.

We definitely need to consider the basement dweller negative EBITDA (Operating) margins.

Absent employee stock compensation, these would be positive today.

I’ll bet that makes you think about future dilution when the company issues a lot more shares to those folks. Yes, it’s not ideal. But it’s commonplace in emerging tech.

Many employees at such firms are willing to trade some cash now for stakes in the future they help build.

If you object, SNOW, and probably a lot of emerging tech, aren’t for you.

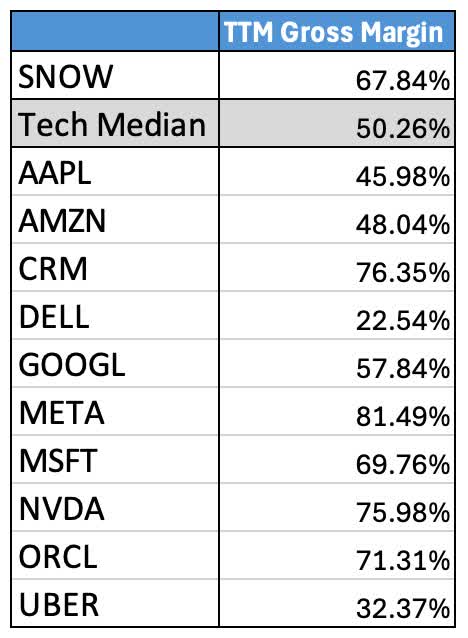

As to the core economics of the business, look at how SNOW’s trailing 12-month gross margin compares with those of other big-name companies.

Analyst compilation based on Seeking Alpha Profitability presentations

SNOW is not number one. But it’s standing is very respectable. That’s especially given that SNOW is so new. The others are all very well established.

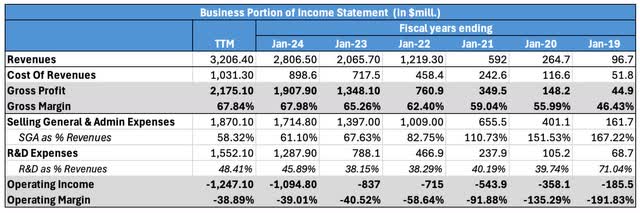

Look now at highlights from SNOW’s income statements. I refer to this as the “business” portion of the statement. (It excludes non-business items such as capital costs, M&A-related costs, tax strategies, etc.)

Analyst compilation based on Seeking Alpha Financials presentation

Look at the gross margin trend. Much Cost of Sales is variable. So, it’s hard for increases in sales to automatically boost gross margin. Changes tend to be gradual as companies get more or less efficient. I’m satisfied with SNOW’s gradual improvement.

Operating (or EBITDA) margin is very different. These costs are largely fixed. Much is determined by company choice.

Notice first, how the operating margin is trending upward. That’s what I need to see when it’s below zero.

Second, notice the impact of R&D.

This is purely discretionary. And at this stage of its life, we WANT the company to be doing a lot of this. It’s still building up its capabilities.

We also want the company to be spending for customer acquisition.

The only catch is whether the company can afford this.

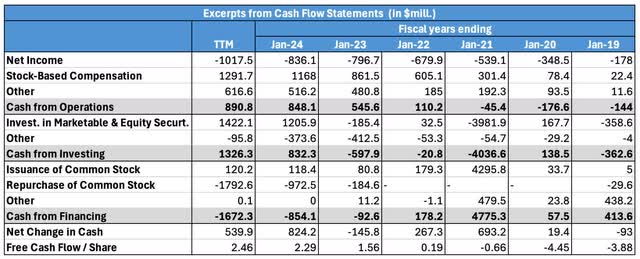

We see here, in highlights from SNOW’s annual Cash Flow statements that it can well afford to keep building its business.

Analyst compilation based on Seeking Alpha Financials presentation

Cash from Operations would already be in the black without non-cash charges (such as employee stock compensation).

Cash from Investing reflects share buybacks. Those seem wise now. SNOW will have to give employees lots of stock. And Wall Street already pushed the price down.

Notice too how the annual change in cash (which, including cash equivalents and short-term investments, was $3.3 billion at the end of the latest quarter). That’s great for an early-stage company.

Note, too, the trend in free cash flow.

Also, management mentioned on the last earnings call that “[w]e continue to see approximately 80% of our customers paying annually in advance.” That helps! Customers wouldn’t do that if they worried about SNOW’s viability.

SNOW has nothing in common with the nonsense-companies that imploded during the circa-2000 dot-com bubble. SNOW is not cash-burning its way to oblivion.

Meanwhile, the last earnings release landed on the Street with an unpleasant thud. The stock dropped 14.7% on August 22, the next day.

Stuff happens. Companies are watching spending now.

And management cited an unnamed security breach (not involving SNOW) that gave customers pause. Psst… I’ll bet they were referring to CrowdStrike (CRWD).

My eyes really rolled at some of the analysts referred to in the Seeking Alpha news story.

[T]he fiscal second quarter results were good, but perhaps not enough.

****

[W]aning optimization headwinds and emerging new product initiatives should support growth, but investors may need more concrete signals to get onboard.

I wonder if any of those analysts were ever involved in building a new business. It’s bumpy.

Concrete signals are for established businesses with established operations. Sensible forecasting requires historical experience (precedent, data).

(Back in my Reuters days, I tried to push a premium stock screener aimed at individual investors. My boss asked how much revenue it would generate in five years. I said, “I’ll let you know in five years.” The rest of the conversation did not go well.)

Newness necessarily involves doing, experiencing, learning and adjustment. Many call it trial and error.

Absent that, the emerging part of emerging growth couldn’t exist. Those who invest in this theme need to accept that.

Risks

One big risk involves competition.

The other involves the quarterly guidance/reporting angst. Investors who demand “concrete signals” will periodically find reasons to dump stock, as they did on August 22nd.

I covered those in the preceding sections.

What to do About SNOW Stock

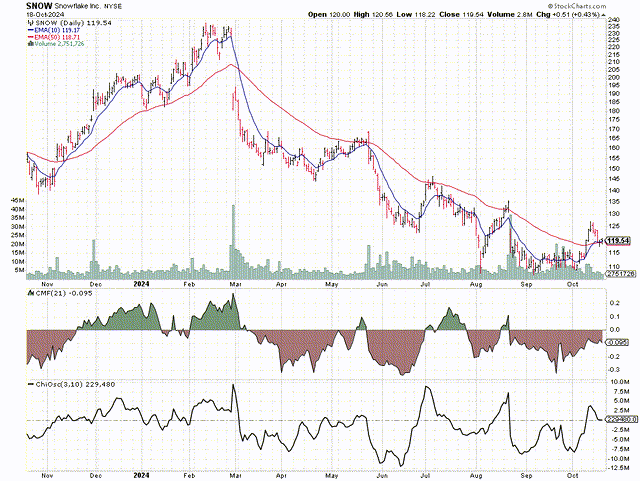

The price chart tells us many on the Street are uncomfortable with SNOW

The stock’s big downslope speaks for itself.

In recent days, the 10-day exponential moving average (EMA) turned up and toward the 50-day EMA. But the very latest price action suggests that may not last.

Consider, too, Chaikin Money Flow (CMF) and the Chaikin Oscillator (CO). Both measure which party to trades is more motivated. CMF does it for institutional investors. CO does it for the market in general.

Both indicators tell us sellers are more motivated. So short term, the stock still faces headwinds.

As noted above, investors hated the latest earnings report.

Clearly, SNOW is only for risk-tolerant contrarians with long time horizons. You need the sort of mindset early AMZN investors, like William Miller, had.

As I’ve said before, my investment stance depends mainly on whether I think a stock will be better than, in line with, or worse than market.

Here’s how I apply that to the Seeking Alpha rating system:

- “Strong Buy” means I see the stock as being better than the market and I’m bullish about the direction of the market.

- “Buy” means I see the stock as being better than the market but am not confident about the market’s near-term direction.

- “Hold” means I see the stock as moving in line with the market.

- “Sell” means I see the stock as being worse than the market but am not confident about the market’s near-term direction.

- “Strong Sell” means I see the stock as being worse than the market and I’m bearish about the direction of the market.

For those whose mindsets are akin to those that motivated Miller with his investment in AMZN, I apply this scale to rate SNOW as a “Buy.”

That said, SNOW is out there on the reward-risk scale. So, carefully consider your risk tolerance and investment horizon.

Speaking for myself, I’m too old to take on that much risk. So, I don’t and won’t personally own SNOW. But I want to make a case for those whose own investment situations may be different.

Analyst’s Disclosure: I/we have no stock, option or similar derivative position in any of the companies mentioned, and no plans to initiate any such positions within the next 72 hours. I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it (other than from Seeking Alpha). I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.

Seeking Alpha’s Disclosure: Past performance is no guarantee of future results. No recommendation or advice is being given as to whether any investment is suitable for a particular investor. Any views or opinions expressed above may not reflect those of Seeking Alpha as a whole. Seeking Alpha is not a licensed securities dealer, broker or US investment adviser or investment bank. Our analysts are third party authors that include both professional investors and individual investors who may not be licensed or certified by any institute or regulatory body.