Summary:

- Intel Corporation’s Q3 ’24 results showed impairments and write-offs, but the core business performance was better than expected, though not an inflection point in its turnaround.

- Intel’s aggressive node development plan still lags behind TSMC and Samsung, impacting its ability to compete in high-end microchips.

- Despite strong early 2024 sales, Intel’s Client Computing Group and Data Center & AI segment show mixed performance, with declining INTC margins and sales volatility.

FinkAvenue

Investment Thesis

On October 31, 2024, I joined Seeking Alpha’s news team to provide a real-time analysis of Intel Corporation’s (NASDAQ:INTC) Q3 ’24 results. It was my first time participating in news coverage. I had my Excel sheet prepared with all historical data and analysts’ consensus estimates, counting down the minutes to the market close when Intel was scheduled to publish its earnings. I was a bit nervous and braced for impact. I knew what was coming.

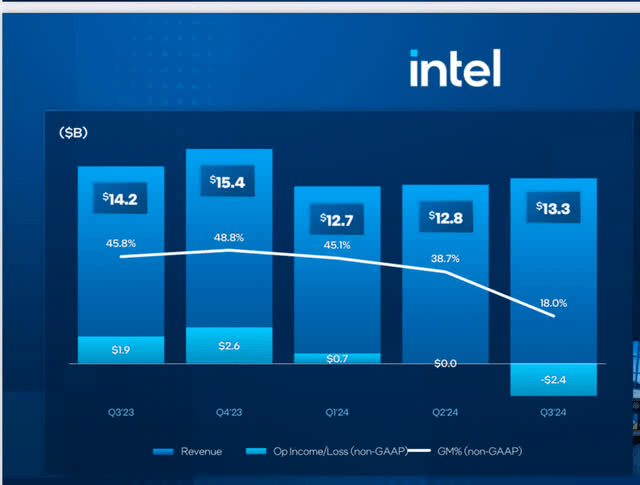

Two weeks earlier, I warned investors that they should expect impairments and write-offs, complicating Intel’s Q3 ’24 financials. I wasn’t wrong. When the results finally came out, the gross margin felt like a figure from another company. EPS completely missed the Wall Street consensus. The culprit; non-cash, non-recurring expenses seeping into COGS and non-operating cost lines. I quickly started sifting through these items to uncover what quickly appeared a better-than-expected core business performance. But as I watched the ticker soar in post-market trading, I couldn’t help but think that this quarter is far from being an inflection point in Intel’s turnaround story. Here’s why.

Intel

Catching Up In Node Process

In June 2020, Jim Keller, a veteran chip designer, handed his notice to Intel’s CEO. In the months leading to his resignation, he spent a lot of time trying to convince his boss to outsource the production of his designs to the likes of Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company Limited (TSM) aka TSMC instead of Intel’s fabrication facilities.

Keller is one of the most renowned chip designers in an industry notorious for a talent shortage. One can only imagine his frustration, working hard to draw spectacular designs incorporating the most cutting-edge architecture and the latest trends, only to find them shelved because the fabrication team at Intel couldn’t manufacture them. On the other hand, one can certainly sympathize with management’s predicament. Leaving the foundry behind is a hard pill to swallow. The company’s fabrication facilities constitute a big chunk of its book value, the very same account that many investors highlight to argue that Intel is undervalued.

A year after Keller’s resignation, Intel told investors it plans to catch up with its peers within four years. Their plan? Develop five generations of node architectures in just four years, an unprecedented pace of node development that has traditionally followed Moore’s law, which observes that a new node generation, defined as a doubling of transistor density, occurs every two years. In normal circumstances, these 5 nodes would have taken 10 years. Perhaps it was a bit easier for Intel because they were walking a trodden path behind the chip manufacturing pioneers such as Samsung Electronics Co., Ltd. (OTCPK:SSNLF) and Taiwan Semiconductor, learning from their mistakes and successes. In any case, Intel pulled through. Next year, they’ll roll out their 5th node generation since 2021, the 18A.

But what happened is that Intel’s peers have also accelerated their development cycles beyond Moore’s law. When Intel releases its 18A architecture next year, TSM and Samsung will be rolling out their 2nm chips. Based on TSM’s internal assessment, Intel’s future 18A chips are at bar with TSM’s current 3nm chips, while TSM’s 2nm chip is far superior. This means at least another year of Intel lagging TSM and Samsung.

Our internal assessment shows that our N3P, now I repeat, N3P technology, demonstrated comparable PPA to 18A, my competitors’ technology, but with an earlier time to market, better technology, maturity, and much better cost. In fact, let me repeat, our 2-nanometer technology without backside power is more advanced than both N3P and 18A and will be the semiconductor industry’s most advanced technology when it is introduced in 2025 — C.C Wei, TSM CEO, Q3 23 Earnings Call.

Impact on Sales

It is important to put this technological gap into perspective when assessing its impact on Intel’s sales. Intel’s loss is primarily concentrated in the high-end microchips. Many consumers, including myself, are happy with a 3 or 4-generation old Intel CPU. I have one and it works just fine. But for a competitive gamer or a brokerage company competing with other firms to close trades, having the latest and fastest microchips is paramount. This is why, despite being behind peers for nearly a decade (Intel’s problems started with the 10nm chip in 2016-2017), Intel still turned $13.3 billion in sales last quarter.

But don’t get me wrong. The high-end market is huge. Intel lost Apple as a customer in 2020 because they failed to deliver the 10nm and 7nm chips in time, encouraging Apple to design its chips and manufacture them at TSM.

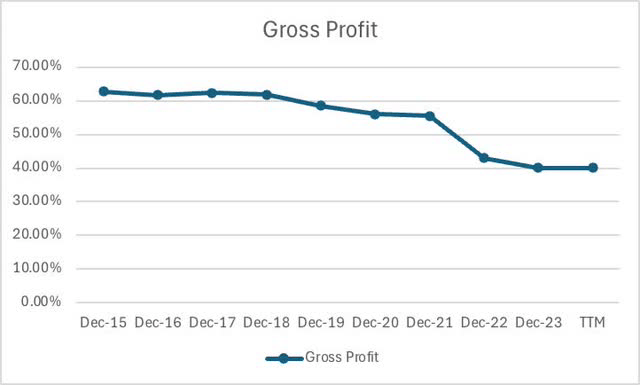

The loss of the premium market has had its toll on Intel’s gross margins, too, as shown in the chart below. As a marketing gimmick, Advanced Micro Devices, Inc. (AMD) posts a comparison between its latest microchips and those of Intel, exacerbating the reputational damage.

Graph created by the author based on compiled figures from Seeking Alpha

The fact that these dynamics will persist even after the rollout of the much-touted 18A node is concerning.

Recent Performance

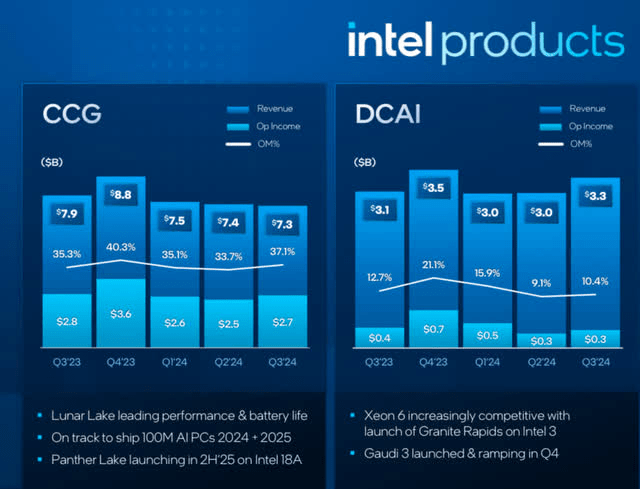

Intel’s Client Computing Group (“CCG”), which includes sales of microchips used in Personal Computers such as CPUs, GPUs, and chipsets has had a strong start in the first half of 2024. However, in Q3, CCG sales declined to $7.3 billion, down 6.4% YoY, suggesting that the company’s AI CPU products, sold under the Core Ultra brand, might be losing momentum after early adopters lifted sales in the first half of the year. It’s worth noting that at least some parts (Chiplets) of the Ultra Core line are manufactured in TSM’s fabs, not Intel’s, with plans to gradually bring production in-house in the coming quarters.

Intel

It is even harder to decipher a trend in Intel’s Data Center & AI (“DCAI”) segment. Sales were flat in the first half of 2024, but in Q3, we saw sales up 9% YoY, hitting $3.4 billion. This figure is still lower than what Intel used to turn in the data center market before budgets shifted to general-purpose graphics computing units “GPGPUs” used in AI inference and training. Intel missed a great opportunity in the GPGPU market, despite acknowledging this trend to shareholders since at least 2017. Intel decided to go on a different path, incorporating neural processing units in its existing product portfolio, as is the case in its Core Ultra client CPUs, and Xeon Scalable Processors for data centers.

I believe that the natural trajectory of Intel’s current portfolio is expansion in niche markets beyond Large Language Models (“LLM”) such as certain medical applications leveraging AI in cost-effective, moderate workload applications. It is worth noting that Intel’s Guadi AI accelerators are designed to compete with Nvidia’s GPUs in the LLM training and inference markets. However, they appear to have failed to gain momentum in terms of market share, notwithstanding sales growth that mirrors an expanding market rather than the product’s success and market acceptance.

Margins

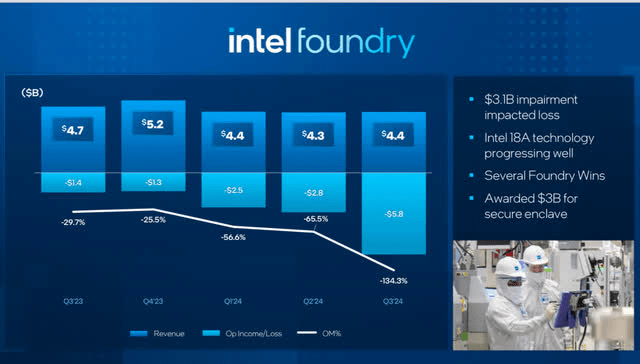

Starting this year, Intel began running its Foundry business as a separate entity, separating its sales and operating income accounts from its products business.

Last quarter, records show that Intel’s CCG business operating income remained relatively flat despite the 6.4% decrease in sales, thanks to a 200 basis points increase in operating margins from 35% to 37%. DCAI, on the other hand, experienced opposite dynamics, with margins shrinking 230 basis points to 10.4%, offsetting the 9% sales increase.

At the same time, Intel’s Foundry business continues to report losses. At this point, I’m not sure if they’re subsidizing the margins of Intel’s product lines, since Intel’s product segment is the main customer of Intel Foundry. If Intel Foundry were really independent, they would have stopped operations a long time ago instead of just burning cash. The $3.1 billion write-off is a confirmation that Intel Foundry is too big for its dwindling market share. Even if they catch up with node process development, it is unlikely they’ll bring back lost customers necessary to increase fab utilization rates, at least in the short and medium run. Apple, a former customer, now designs its own chips for MacBooks and is comfortable with a reliable manufacturer such as TSM. AMD has also built a loyal customer base, with the help of Original Equipment Manufacturers (“OEMs”), such as Dell Technologies Inc. (DELL), Lenovo Group Limited (OTCPK:LNVGY), HP Inc. (HPQ), etc., who were happy to see competition rise among their suppliers.

Intel

Final Thoughts and How I Might Be Wrong

Every so often, the difference between investment and speculation can be blurry. With Intel now writing off its foundry assets and shutting down unproductive segments, one can speculate that these measures will solve its profitability problem. With core segment operating income of $12.5 billion, and assuming a Price/EBIT ratio of 8 to 12x, Intel’s valuation falls somewhere between $100 billion and $150 billion. Given a current market cap of $107 billion, Intel falls at the lower end of this range. Still, with all the uncertainty surrounding its turnaround plan, the company is hardly undervalued. I don’t believe that the company can survive another year falling behind in node process development.

Editor’s Note: This article discusses one or more securities that do not trade on a major U.S. exchange. Please be aware of the risks associated with these stocks.

Analyst’s Disclosure: I/we have no stock, option or similar derivative position in any of the companies mentioned, and no plans to initiate any such positions within the next 72 hours. I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it (other than from Seeking Alpha). I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.

Seeking Alpha’s Disclosure: Past performance is no guarantee of future results. No recommendation or advice is being given as to whether any investment is suitable for a particular investor. Any views or opinions expressed above may not reflect those of Seeking Alpha as a whole. Seeking Alpha is not a licensed securities dealer, broker or US investment adviser or investment bank. Our analysts are third party authors that include both professional investors and individual investors who may not be licensed or certified by any institute or regulatory body.