Summary:

- Mullen lacks the innovative drive necessary to compete in the cutthroat EV market.

- The company’s “fully-assembled in the US” vehicles depend heavily on Chinese tech and design.

- The acquisition of Electric Last Mile Solutions brought IP assets for Class 1 and 3 vans; however, the nature of Mullen’s relationship with the original patent assignees is unclear.

Mario Tama

Investment Thesis

Shares of Mullen Automotive (NASDAQ:MULN) soared by 8% on the news of their initial delivery on Friday, meeting the deadline on the last day, echoing the triumph of a procrastinating college student with a term paper due. But the euphoria was short-lived. Shares were quick to tumble, declining by a sobering 15% today (Monday, 3rd of April), leaving us all with the lingering question: are Mullen’s manufacturing facilities really up and running, or did they just send out a few shiny samples to dazzle the crowd.

In a previous article, I noted the company’s desperate need for capital and the impending dilution as it builds up its manufacturing capacity. In this article, we turn our attention to the company’s competitive moat or lack thereof. Based on an analysis of the company’s IP portfolio, I have come to the conclusion that Mullen lacks the innovative drive needed to survive in this cutthroat market, adding to the reasons to pass on this company.

When Made in China is Lost in Translation

Mullen’s emphasis on its “fully-assembled in the US” vehicles has led to a lack of clarity regarding its business model and its dependence on Chinese manufacturers and tech. Shareholders are left in the dark about the company’s true operations and its competitive advantages in the EV market, raising concerns about the sustainability of its position in the industry. Upon closer examination, it becomes evident that Mullen is essentially rebranding Chinese vehicles, a fact that has not been explicitly communicated to shareholders.

Mullen Automotive Home Page

The following paragraphs seek to provide a comprehensive analysis of Mullen’s patent portfolio based on information from Google Patents Database and the US Patent Office website. However, given that Mullen is a conglomerate of various failed businesses and subsidiaries, some patents may have been overlooked in this analysis. If you are aware of any additional patents or relevant information pertaining to Mullen, please leave a comment below. By fostering an open and collaborative discussion, I hope to create a platform where the investment community can share information and share light on Mullen’s true IP assets, helping create a more accurate and informative resource for investors and EV enthusiasts within the industry.

Mullen’s origins can be traced back to 2014 when it was established through the merger of car distributor Mullen Motors and bankrupt EV manufacturer CODA Automotive. Although CODA’s car designs were unappealing to customers (embodying an ’80s vibe) and had limited sales potential, their innovative technology and entrepreneurial spirit were highly valued by industry observers. I don’t believe Mullen inherited this entrepreneurial and innovative culture, as the company has not generated any significant patents since the merger, and in fact, it appears it didn’t inherit CODA’s patents either.

Out of CODA’s 21 patents/patent families, 20 are assigned to a Collateral Agent controlled by CODA’s creditors, while one patent (WO2013112179A1) related to creep control is still owned by CODA, which presumably is now controlled by Mullen. Despite CODA’s technical moat, Mullen doesn’t seem to have inherited much from the acquisition. Furthermore, Mullen has abandoned plans to produce the CODA Sedan, rebranded “Mullen 700e”, following a recall order by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration in 2014, possibly because it lost the patents to debt holders.

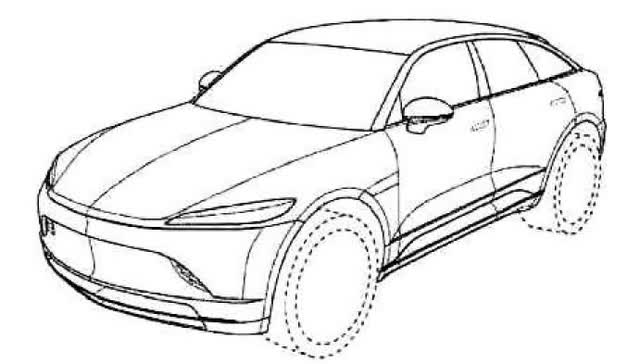

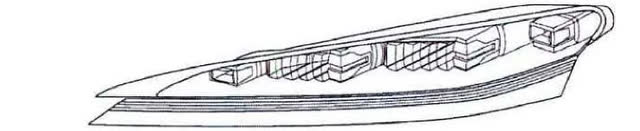

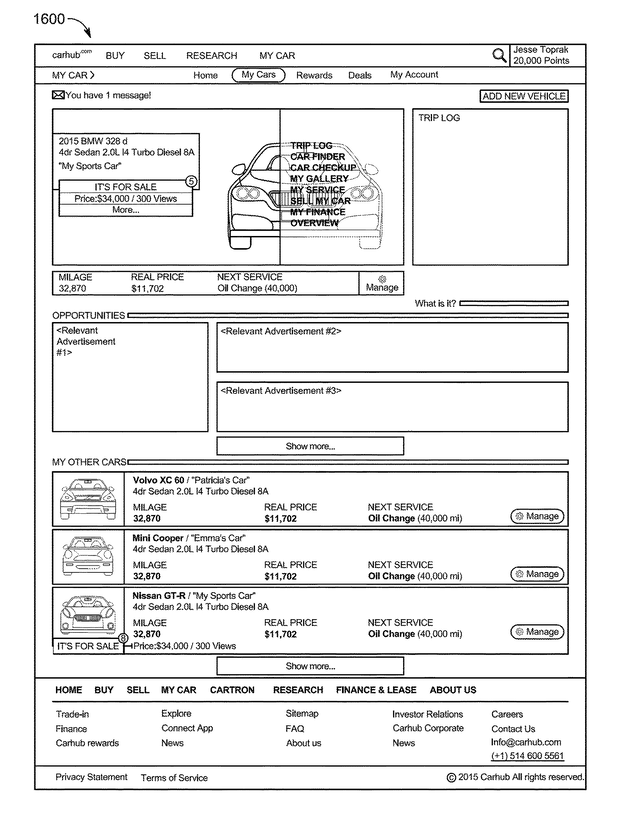

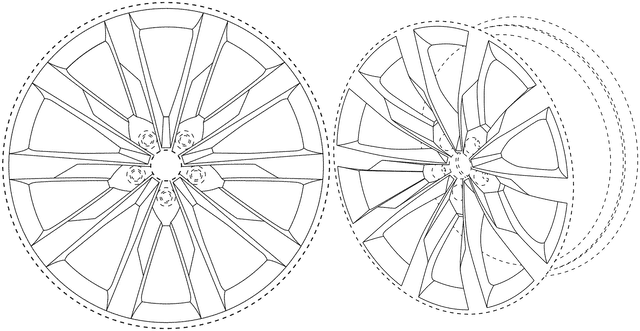

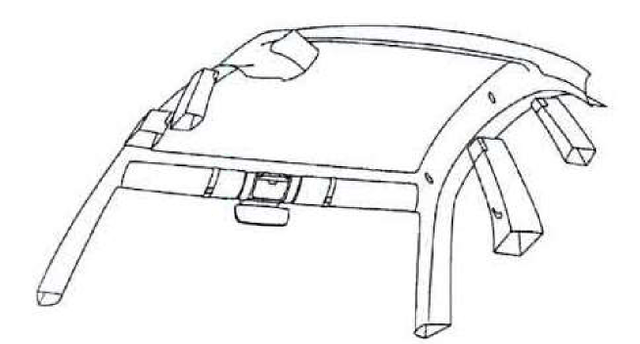

As I dug deeper into Mullen’s subsidiaries, I stumbled upon Mullen Technologies, which boasts around eight patents. These include a pending patent for a vehicle roof design “CR 2021,05,68S“, what seems to be the design for the Mullen Five SUV body “CR 2021,05,64S“, and patents for headlights “CR 2021,05,65S“, interior “CR 2021,05,70S“, vehicle seats “CR 2021,05,69S” and wheel rim “US D97,498,8S1” of the same model. Sadly, nothing pertains to the engine or any technical aspects of the vehicles. Additionally, there is another patent for a vehicle management service, “US 2017,03,375,73A1“, which, from my understanding, relates to a system that aims to streamline the process of buying and selling vehicles, collecting data from a vehicle’s onboard diagnostic system, and merges it with another information such as accident history and maintenance record. In the supplementary diagrams, the inventors use examples of well-known car models, such as the BMW 328, Volvo XC, Mini Cooper, and Nissan GTR. I assume this app was acquired to support Mullen’s car distribution business and its subsidiary, carhub.com. Interestingly, the patent was filed by Carmoxy Inc in 2017 and assigned to Mullen in 2018. However, none of these patents demonstrate technical expertise or reveal any insights into the motor and inner workings of EVs.

Diagnostic Data Reporting System (US Patent Office) Wheel Rim Design (US Patent Office) Vehicle Roof (Google Patent Database) Vehicle Body (Google Patent Database) Headlights Design (Google Patent Database)

Bollinger’s acquisition came with numerous patents, primarily originating from the now-defunct Chinese EV producer Bordrin. While the exact relationship between Bollinger and Bordrin remains unclear (e.g., whether patents come with royalty payments or require a license), it seems likely that Mullen now possesses the patents (and accompanying obligations) that Bordrin had assigned to Bollinger.

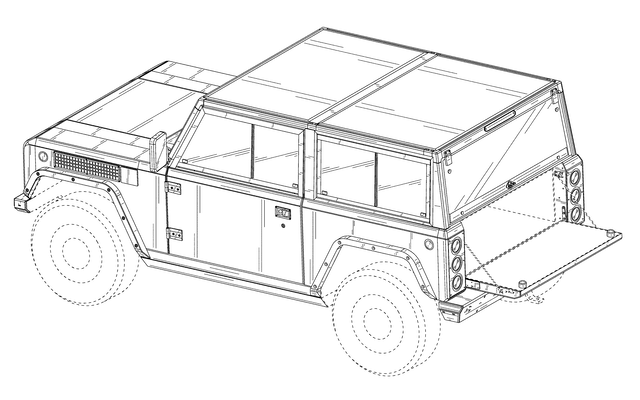

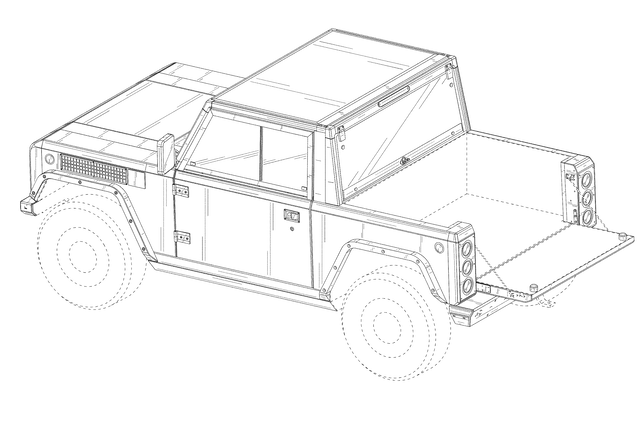

Bollinger’s own contributions to the patent pool are relatively few, mainly focusing on the body design of their B1 SUV, as evident in patent “USD 83,648,7S1” and B2 Pickup, shown in patent “USD 83,602,7S1.” The images below provide a closer look at these design elements.

Bollinger B1 SUV Body Design (US Patent Office) Bollinger B2 Pickup Body Design (US Patent Office)

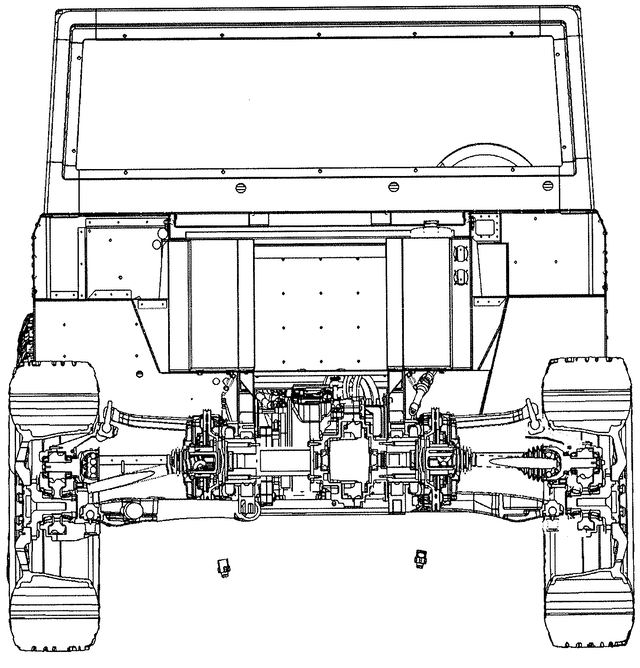

However, Bollinger displayed a more comprehensive technical grasp of the inner workings of an EV, showcasing a patent that tackles critical challenges like weight distribution, torque control, hydraulic cylinder designs for fluctuating vehicle weight, and batter connections, as showcased by patent “US 2021,014,677,6A1.“

US20210146776A1 (US Patent Office)

When examining the design of the components, it appears that Bollinger depended heavily on its supplier Bordrin. Besides the ones mentioned above, most of the other patents I discovered assigned to Bollinger were filed and developed by its Chinese partner, Bordrin. These include a patent for controlling creep torque ” US 987,335,3B1” a battery cooling system “US 968,019,0B1” a portable charging system that allows EVs to charge each other “US 104,069,24B2“, an integrated electric box and diagnostic system “US 971,842,0B1” and finally a system for battery temperature control “US 106,472,18B1“. Most of these patents are Active in the US, developed by Bordrin, and assigned to Bollinger Motors, highlighting the extent of their reliance on their Chinese partner.

The design of Class 1 and 3 vans that Mullen recently shipped were inherited from the acquisition of Electric Last Mile Solutions after going bankrupt last year. Mullen’s management stated that they own the IP assets of these vans, but upon investigation, I found that ELMS patents seem to be assigned to two entities, SF Motors and Chongqing Jinkang Co Ltd, such as patent (US20200331476A1), which is linked to an invention that allows an autonomous vehicle to change lanes and patent (US 2019,039,404,6A1) that allows remote software update. You can find the patent list here.

There isn’t much information about Chongqing Jinkang Co Ltd, but it is worth mentioning that ELMS was formed via a SPAC deal with SF Motors, a subsidy of a Chinese company called Sokon Industry Group, which to the best of my knowledge, is now referred to as Seres Group (SHA:601127).

Now that ELMS is part of Mullen, I am not sure about the nature of the relationship between the assignees recorded on the patent filings and Mullen.

Summary

In conclusion, Mullen appears to lack the necessary innovation and technical expertise to compete effectively in the EV market. With a confusing business model and heavy reliance on Chinese manufacturers and technology, the company’s long-term sustainability and competitiveness are in question.

Thus, even if Mullen actually built its manufacturing capabilities to deliver the 6,000 van order in a reasonable time (which I highly doubt), the lack of technological moat casts a shadow over its long-term prospects. Investors should proceed with caution, and a sustained rebound is, in my view, unlikely.

Editor’s Note: This article covers one or more microcap stocks. Please be aware of the risks associated with these stocks.

Analyst’s Disclosure: I/we have no stock, option or similar derivative position in any of the companies mentioned, and no plans to initiate any such positions within the next 72 hours. I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it (other than from Seeking Alpha). I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.

Seeking Alpha’s Disclosure: Past performance is no guarantee of future results. No recommendation or advice is being given as to whether any investment is suitable for a particular investor. Any views or opinions expressed above may not reflect those of Seeking Alpha as a whole. Seeking Alpha is not a licensed securities dealer, broker or US investment adviser or investment bank. Our analysts are third party authors that include both professional investors and individual investors who may not be licensed or certified by any institute or regulatory body.