Summary:

- The analogy between today’s streamer dilemma and the mess in the steel industry was solved by Mr. JPMorgan by forming U.S. Steel.

- Netflix, Inc. is the most logical consolidator for a sector still in search of a business model that can find profitability despite worsening glut.

- Netflix has the head start that can lead a consolidation that could be the only long-term answer to a business model that makes money for all.

Above: Family formation levels are sinking so competition for paying eyeballs over the next decade will become even tougher unless there is consolidation of at least three of the top streamers. skynesher

In 1985, author and university media professor Neil Postman (d.2004) wrote a devastating treatise on the media entitled, “Amusing ourselves to Death.” His premise was that America’s media had converted real news events into entertainment. “All media has become a vaudeville act, its object not to inform, but entertain an adolescent audience.” His implication was prescient, “We were no longer a nation of citizens, but a nation of audiences.” He followed this up with another book in 1992 called “Technopoly” introducing the idea that information of all kinds had become a form of garbage—nothing was important, everything was instantly used, then discarded, as an audience awaited the next attention getter developed by techies.

Consider the bacillus of selfies that has infected the audience. The compulsion to record one’s self grinning stupidly into a smartphone for no apparent reason other than to feed a desperate need for attention illuminates our time. It’s streaming you don’t have to pay for. You and your friends and family literally make your own vaudeville shows for telecast on your little phone. Fame is fungible. You imitate the idiocies of celebrities you see in media and thus become one.

Postman’s vision was clearly vindicated. Even up to the minute, we have the vaudeville show of the Trump/media/social and “justice system” providing a daily diet of entertainment for the portion of the public now addicted to the media, both social and mainstream. No matter what one’s take on the case itself. it really doesn’t matter whether one is a Donald Trump fan or hater. What counts is the semblance of importance, where nothing of real importance is going on other than the vaudeville of media alluded to by Postman.

We’re consuming the Trump case as entertainment—little else. As we buy everything—its entertainment. Big public legal proceedings against celebrities are, of course, nothing new. But what is new is that such events when everything and anything from the absurd to the profound becomes little more than inane blabber on social media going viral is all people want. And, as Postman said, it all winds up as garbage in a matter of hours.

The great streaming glut

google

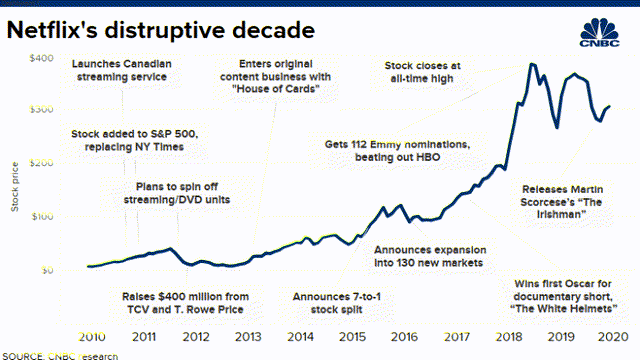

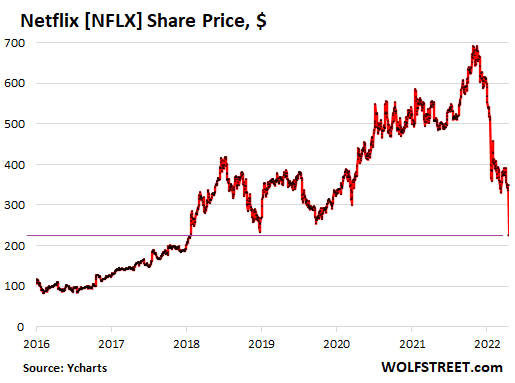

Above: There has been some price recovery in Netflix, Inc. (NASDAQ:NFLX), but neither it nor its many competitors have yet figured out how to confront glut.

Amid this crazy-quilt world of me-me-me obsession, we have injected the watershed transformation of all media content to streaming TV. And the early success of Netflix, as industry pioneer, spawned the massive competitive madhouse investors must try to sift out to judge who the winners and losers will be so they can make their bets.

In every earnings call, for every streamer, we get the same rhetoric, with the same tired ideas in attempts to build a viable rationale in the minds of investors that resembles a reformed business model that makes sense. You are urged to buy the bull scenarios: we’re slashing costs, building up our “franchises,” plunging our “tent poles” deeper into the group, develop new blockbusters the public will love.

All that is conventional wisdom some analysts and investors buy, others remain skeptics. There are nuances between peers that may nudge an investor towards or away from a given mega-platform stock. But beneath it all, nobody is really addressing the presence of the aforementioned 600-pound gorilla shaking the cage bars as the earnings call clichés mount with each quarter. And that roar is glut. The gorilla is that there cannot be a case made for the existence of too many streaming providers in the marketplace.

The ability of humans to turn out enough new sets of eyeballs to absorb the massive glut of programming is limited. This very fact took some time to jell, but was finally recognized in 2022.

Underserved had become sated, and sated has now become over-sated glut. Supply and demand are out of whack. Slicing and dicing audiences by precise demos under the theory that a viable economic model can be built with a gaggle of niches under a big corporate umbrella can be questioned. The reason is simple: the sheer costs of producing much content has been blown so out of whack with their potential to become profitable that niche audiences simply can’t work. And mega blockbusters are as rare as the appearance of Haley’s comet.

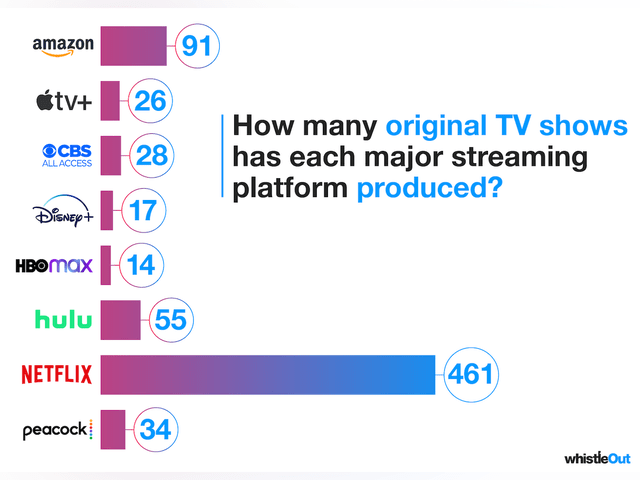

The glut is simple to appraise: At any given hour, amass the total program choices available to subscribers and you stop counting at ~500 to 800. The top five multi-platform streamers have a combined audience of 1.26b. Now, assume conservatively that each subscriber has at least 3 main services among those noted here or others lower on the food chain. That carves the real world market of total unduplicated U.S. subscribers to ~ 300m. The overall demo of streaming subscribers leans young, but new household formation as a fresh blood injector into the existing viewership potential imparts a more disturbing vision.

In the post WW2 period of returning GIs as well as post-Depression babies maturation, the U.S. averaged ~1.5m new household formations per year through 1955. In 2015, before the massive streaming explosion really got underway, new household formation hit 2.26b per year. Last year that number dropped to 2m. Given the continuing trend to late marriages, inflation and permanent job losses resulting from technological breakthroughs, it’s in decline. Even more depressing for streamers is the projection of 7.6m total new households to be added between 2030 and 2040, which is ~700,000 per year.

The majority of those households will be from older demos reforming life styles in later life post children. At the same time, we have the prospect that the streaming service market will become more price sensitive as new households will tend to come from older demographics among people with fixed or lower incomes to spend on discretionary services. (U.S. Urban studies).

Bear in mind, these projections of new household formations do take into account that not all fall into the traditional nuclear family structure. They do count roommates, married or not, or couplings that do not figure as traditional.

What all this means is that streaming services who believe that market shares and revenue potential gains will come from new arrivals courtesy of the birth and maturation rates of the populace are kidding themselves. Add that to those streamers pledging exciting new content as the solution to maintaining churn rates low or even ad supported models to sustain revenues, may also be living in something of a fool’s paradise.

The endgame is clear: Too much content chasing too few eyeballs now and in the foreseeable future.

Let’s turn to the churn factor as part of the gorilla’s growl:

A recent survey of subscribers reasons for canceling:

- Lack of interest in content: 44%.

- Price: 33%.

- Too many subs, need to cut down: 14%

- No time to watch so much: 8%

- Offensive material: 2%.

Above: By any measure, NFLX has produced more reasons to stand as the must-have of all streaming services, but it still isn’t the answer.

So, more than half of those canceling cite factors seemingly unrelated to content. It’s a price business, a commodity. And the hefty 44% who say they see nothing of interest to watch on a service disguises the real issues: sameness of genre and theme, too many series that overstay their welcomes, and without question, a percentage of subscribers grown weary, if not outright angered by, the persistence of woke agendas in too many shows. Those cancelers are probably disinclined to reveal to poll takers their true resentment of woke content.

So, it appears to us that the choices are clear: if content “our subscribers will love,” as the c-suite mantra goes, isn’t the answer, or organic growth isn’t promising, it appears that there is no other choice but consolidation, which implicitly could mean a reduction in total available content.

After all, a quick glance back at the good old golden days of network TV’s kingdom shows we effectively gave audiences a choice between the content of three, later four, major TV networks, a bit of local programming and sports. The audiences for top shows back then were in the strong double-digit millions, unheard of today for anything but NFL games. A lot less content, a lot less choice, a lot bigger audience not yet diverted by social media, cable, smartphone gabbing, endless hours of website browsing. What you watched was a choice between best, tolerable, or marginally watchable content. Prime time was 3 hours X four networks = 12 shows take it or leave it. Otherwise, you found something else to do.

Mr. J.P. Morgan: Where are you now that we need you?

Let’s begin by stipulating that, yes, our analogy here isn’t perfect. And yes, the feisty Anti-Trust bureaucracy of today is going to sniff any such move out fast and frenetically wave all kinds of caution flags to a massive consolidation of a sector. But that’s a lengthy, twisted discussion for another forum. As is a deep down financial analysis of how a consolidation would work. Where there’s a will, there’s a way.

Our modest proposal is simpler:

No matter what the services see as their ultimate salvation does not appear to be viable in terms of real world possibilities for sector demographic growth. Content isn’t king, because it alone cannot be a sustainable value that presents a rationale not to cancel once it begins to age out. It is also far too costly to develop. And the nuclear testing of AI which could write hour long TV dramas in seconds for free threatens to reduce content to messages from Stanley Kubrick’s Hal in 2001: A Space Odyssey. Pricing wars and ad support models tell us that streaming services have become a pure commodity. Customers understand they can’t get all they want from one service. Or perhaps even two. But if they get most of what they want, at a price that doesn’t jar them, they’ll stick. But for how long?

And can the service depend on price increases over an extended period that will attract new buyers and hold onto existing ones? Problematical. If 20 services essentially offering generic content of one kind or another can’t make money, can 6 consolidated industry leaders which have acquired their competitors and killed off a sizeable chunk of its me-too programming, make money? The chances are improving. Take it one step further. Can a theoretical United States Television Streaming Corporation commanding 50%+ of the total market make money? Answer, yes without question.

You keep control on your pricing to give the consumer the best deal relative to cost and at the same time, put the shekels in the treasury at an ever increasing rate. You can save tons of cash in marketing programs. You can finance new content on a defined budget in a defined time line. And you won’t be dragged down by humongous debt to achieve an EBITDA that gladdens shareholder hearts.

Above: When it stood well as an investor darling, the news flow was the best friend of the stock’s meteoric rise–and ultimately its tanking.

The U.S. Steel analogy says: get going, Netflix

Here are a few of the prevailing facts about the steel business in 1901 that annoyed good old J.P. There were far too many companies making the same type products, bidding one another to death for contracts, especially on the blooming railroad business. The process components of all the steel makers were the same. Everyone used the same fuel to fire their cauldrons, the same equipment to form their products, the same Bessemer techniques. And old JP’s middle name may have been Pierpont, but let’s call him “Predator.” He was a man who never passed a shot to strike at someone else’s stupidity, weakness, or refusal to face facts.

Steelmakers concentrated in those industrial areas close to where both raw materials, cities and municipalities were nearby. The duplication of costs in manufacturing, sales, labor, land and construction of plants was rife. The result: nobody was making any money to speak of. They were all, in essence, engaged in a suicidal death spiral until someone had a better idea. That someone was J.P.

His idea, disarmingly simple, was this: take the top component companies (ex: Carnegie Steel) and put them together under one corporate structure. Consolidate overheads from the corporate offices to research, to the mill floors at every level. Present a stronger negotiating stance with unions. Let whatever type of product a component company of the combination excelled in become the product of U.S. Steel. Price steel that provided a profit for the mill, a better product sold at a reasonable price to customers and form the basis for a great company in the future that would become the bluest of blue chip stocks on the Dow.

Supply the force of your money to overwhelm resistance and take billions off the table for your trouble.

The Netflix Analogy

By any measure, the chances are that NFLX will sustain a commanding lead in total subscribers retained over a fixed duration—you pick it, five, ten years, it doesn’t matter. It’s head start, genre coverage, and ability to manage pricing due to its subscriber base is bigger than competitors. Start with them and pick up Paramount Global (PARA) and Warner Bros. Discovery (WBD) for openers. Disney+ Amazon Prime have other businesses far more crucial to their earnings over time to consider the value of n a mega-merger under NFLX. For Apple (AAPL), streaming TV is little more than a petty cash cigar box in a desk drawer somewhere in Cupertino. Amazon’s daily bread comes from AWS and running its digital retail kingdom. Streaming to them is clearly a “why not us?” decision someone made implying a dilettantish foray into a vertical that in the end made no real difference in the final accounting of what comprised their biggest, existing money pots.

But consider this: NFLX, WBD and Paramount bundled together in a single company would begin life with ~$95.4b in revenues. Using that as a starter, they could then sift through the dozens of small, tier two and three operators with discernable market shares or specific money making genres, and get revenues way above $120b annually.

Our calculations indicate that a bump of 10% in operating gross margins across the board of such a company due to massive savings in marketing, content and tech investments, would yield ~$10b in savings. The combined net debt of NFLX, WBD and Paramount Global for 2022 amounted to $78b. Part of the operating savings ex: $10b could not only be aimed at debt service from savings, faster reduction of overall debt and a stronger dividend profile than anyone can ever envision if they continued to operate independently.

All three companies come to the table with a unique history complicated by blunders, misjudgments, victimization by macro events out of their control. They are all still living with the detritus of those misfortunes:

NFLX: Over-invested in much questionable content to feed a maw it saw as much larger than it proved to be, hence losing tons of subscribers and forcing itself into an ad supported model that may prove okay, but is far from certain.

WBD is the creation of the profound blunder that was the AT&T Inc. (T) $85b acquisition of Warner Discovery built off assumptions wrought out of the dizzying, dazzling, algorithms of investment bankers who couldn’t add using all ten fingers and all ten toes.

Paramount was the dream vision turned into a family soap opera nightmare through which heroine Shari Redstone had to fight through tooth and nail with her father, his cronies and bimbos to have her company re-emerge with some semblance of raison d’être to re-emerge as a viable competitor. At this writing, Para is running with the pack. But it is a viable also ran at best—until it either sells off some of its better assets or dumps then entire company and Shari walks into the sunlight a winner. Our bet is on some kind of transaction by year’s end.

But brought together by some visionary banker (if you can find one) or a mega-activist into a J. P. Morgan theory, it would prove that bigger is not only better, but the only way to build a muscular, leader in a space good for itself, its investors, its employees and customers at one fell swoop. The business model: cost efficiency, smarter capital investments, comfortable debt levels, lower churn, bigger market presence.

The combined market cap of the three companies today is $200b, most of which, of course, is NFLX at $152b. That tells us that both WBD and Para are relatively cheap by comparison essentially offering interesting differences in product: a) NFLX as a pure play with core strength in its first mover biggest subscriber role; b) WBD bringing a diverse set of niche platforms, some jewels (HBO) some zircons (too many to mention) and c) Para with its footholds in movie and TV production, its valuable film library, and its genre broadness for kids, young people, quality TV series, cable, and live cinema.

The result in our view provides a formidable response to the question where is the business model here? It is one provider encompassing much of the best of what is available, operating at a lower cost basis that each of the three are currently at, able to sell the service for a stable, ad free high value price with the capacity to add new content on a regular basis without breaking the bank. If the streamers continue to see salvation in going the ad supported route they’ll end up just a 2.0 version of the old broadcast TV model. That means over time, more and more ad time, less and less pure content, churn rate rises.

What this kind of consolidation deal could do is play both offense and defense. It could blunt Disney+ and Amazon with skillful pricing approach: more for less per month. It could achieve creative leadership at less average cost per episode with its buying power and thus fall into a better rhythm with the expectations of subscribers as to content and price.

Meanwhile, what is the best route for investors now, assuming we can’t exhume good old J. P.? All three streamers noted here are at best HOLDs, pending some kind of transactions ahead. Most likely, spin offs or sales of marginal platforms to tier three owners or investor groups, the curating of those platforms of so-so value to hard decisions to either enhance or sell and mostly, find religion in inventive ways to cut content costs. The last of these has now assumed an urgency as the AI atomic bombs are about to explode and begin producing one hour dramas in fifteen seconds at a zero cost.

The sector is no place to make money now, but it could be. Of the three noted, our sense is that while each has some value to recommend it, content, management or tech moats yet to come, the overall best bet is Netflix, Inc. as a sleep-tight stock awaiting a J.P Morgan to awaken its potential.

Analyst’s Disclosure: I/we have no stock, option or similar derivative position in any of the companies mentioned, and no plans to initiate any such positions within the next 72 hours. I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it (other than from Seeking Alpha). I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.

Seeking Alpha’s Disclosure: Past performance is no guarantee of future results. No recommendation or advice is being given as to whether any investment is suitable for a particular investor. Any views or opinions expressed above may not reflect those of Seeking Alpha as a whole. Seeking Alpha is not a licensed securities dealer, broker or US investment adviser or investment bank. Our analysts are third party authors that include both professional investors and individual investors who may not be licensed or certified by any institute or regulatory body.

For in-depth and deep dive research on the casino and gmaing sector, subscribe to The House Edge. New: Free excerpts from our book in progress “The Smartest ever Guide to Gaming Stocks” – free to existing members and new subscribers.