Summary:

- Arrival’s agreement to merge with a SPAC for a second time looks like a creative effort to raise much-needed capital.

- But the de-SPAC faces serious redemption risk, and a concurrent $300 million at the market offering will be hard to pull off.

- Both financing efforts likely don’t get the company all the way through initial production; more capital will be required.

- With a ~$1 billion enterprise value in 2025 needed simply to support modest upside from the current price, ARVL stock looks like an avoid.

Scharfsinn86/iStock via Getty Images

If at first you don’t succeed, try, try again. Electric van manufacturer Arrival (NASDAQ:ARVL) went public in March 2021 via a merger with special purpose acquisition company CIIG Merger Corp. EV optimism had essentially peaked: in retrospect, the top was marked by the parabolic rally and ensuing crash in Lucid Motors (LCID) SPAC Churchill Capital IV just a few weeks earlier.

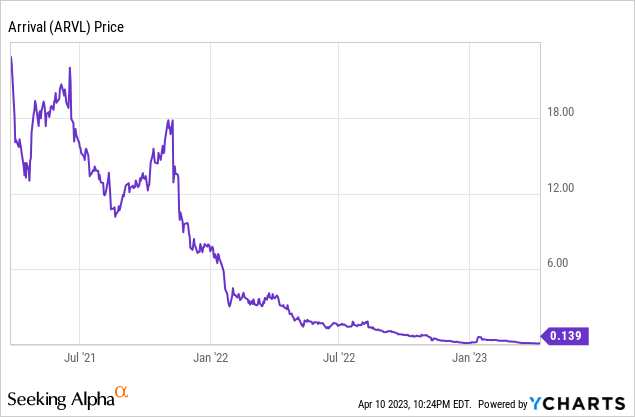

ARVL stock initially cleared its $10 merger price, but as sector optimism cooled and financing concerns increased, shares headed sharply south:

The plunging share price created a vicious circle. Arrival needed to sell more stock to fund itself through initial production. A steadily lower share price, however, meant increasingly higher potential dilution to raise the same amount of cash. The prospect of that dilution in turn led investors to sell more shares; a lower ARVL stock price followed, meaning ever more dilution and so on.

By October of last year, the company itself gave up on an at-the-market facility that was supposed to raise some $300 million. With share issuance no longer “a reliable source of capital“, Arrival announced plans to focus solely on the U.S. market in a bid to preserve the capital that remained.

Less than three weeks later, the company’s third quarter earnings release contained a so-called “going concern warning“. Arrival at the time said that it lacked cash to fund operations for the following twelve months (i.e., through Q3 of this year), a significant problem given that commercial production was (and is) not expected to begin until late 2024.

But this year, it would appear that Arrival has found a pair of lifelines — at least on paper. In March, Arrival entered into a $300 million financing agreement with Westwood Capital, resurrecting its at-the-market sales. Then on Thursday, the company announced it was merging with another SPAC, Kensington Capital Acquisition Corp. V (NYSE:KCGI).

In theory, both deals could provide enough cash to get Arrival to and through production. In practice, however, Arrival’s second de-SPAC merger seems likely to end up with the same disappointing results as the first one.

The Westwood Deal

Again, for a company like Arrival, the need to fund operations by issuing stock creates a vicious circle. In the market of 2020-2021, investors largely ignored this problem: valuations across the EV space were high enough (Arrival’s market cap was ~$14 billion after the initial de-SPAC merger) that funding could occur with relatively modest dilution.

But Arrival’s market cap, at Monday’s close, was under $100 million. Arrival did manage to raise $50 million in February, but under relatively onerous terms. There was seemingly no way for the company itself to raise the funds it needs — an amount that, on a multi-year basis, is in the high nine figures — through a direct share offering.

And so, effectively, Arrival is outsourcing that work to Westwood Capital through a $300 million equity financing. The firm doesn’t come cheap. In exchange for Westwood buying shares at Arrival’s direction, the investment bank gets, upfront, $3 million in stock. The firm also buys the shares at a 3% or 5% discount to the 3-day VWAP (volume-weighted average price).

Immediately, Westwood would own nearly 3% of the company. But Arrival can’t make Westwood buy shares that would let its ownership exceed 5% (or 10%, if Westwood so desires; it likely won’t). So the only way for Arrival to keep selling shares to Westwood and for the firm to not clear the cap on ownership is if Westwood buys the shares from Arrival and then almost immediately dumps them on the open market.

This is a simpler and more common version of the complex financing recently executed by Bed Bath & Beyond (BBBY). And it creates a very real problem for the ARVL stock price. Essentially any rally will be sold into by Westwood. As of Friday’s close, average daily volume year-to-date has been less than 2% of shares outstanding (763.2 million at Feb. 23 of this year); as of this moment, Westwood needs to sell ~300% of shares outstanding to fulfill the $300 million maximum.

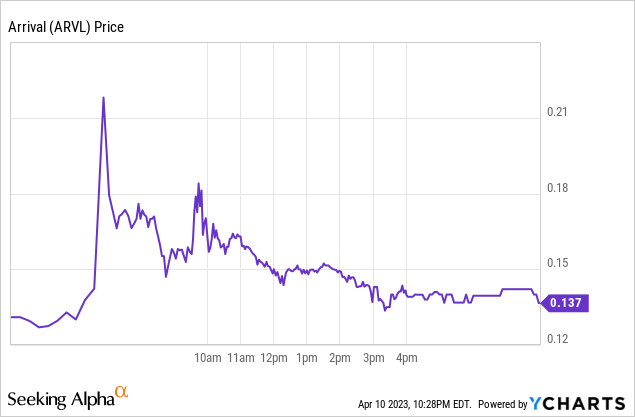

The sheer size of the capital required makes for a delicate tightrope walk. (Indeed, the BBBY agreement was terminated at the end of last month.) And while ARVL no doubt will find rallies from time to time — the stock in fact gained sharply on Monday — the fire hose of equity issuance via Westwood will in turn depress the stock price. Indeed, it’s not hard to imagine that Westwood unloaded a few shares during Monday’s session:

The Second SPAC

In other words, the Westwood deal simply isn’t enough. It’s far from guaranteed that Westwood can raise anywhere near the capital Arrival requires for survival without completely tanking the stock price. And survival is only step one: Arrival still needs to get its XL van into production, raise the cash needed to survive beyond production, and handle ~$200 million in convertible notes which mature in December 2026. (Antara converted ~$122 million in notes into equity; $200 million remain outstanding. Those notes currently trade at 31 cents on the dollar, though they’ve nearly tripled from a November low.)

Arrival needs a quick, large infusion of capital. And so it’s going the SPAC route — again.

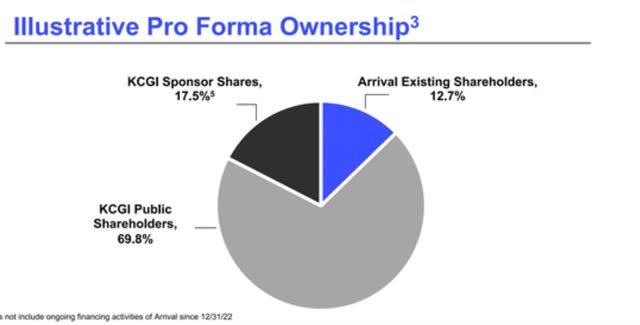

This capital raise, too, is not cheap. Dilution will be extensive. As contemplated, after the merger current Arrival shareholders will own just 12.7% of the company; in fact, at the current price, the SPAC sponsors will have larger ownership:

Arrival/Kensington Capital V merger presentation

That said merger would provide Arrival some breathing room. The $263 million raised (net of expenses) would allow Arrival to throttle back on the Westwood arrangement, and more importantly extend its cash runway.

That incremental cash gives Arrival it a total of $468 million on the balance sheet. The year-end 202 balance of $205 million was forecast to last until late this year; with a guided burn rate of ~$35 million per quarter, the net SPAC proceeds would keep Arrival afloat until, roughly, mid-2025.

XL production is expected to begin in late 2024. And so the path here is to simply survive beyond that point, get the vehicle into production, inspire some confidence in the market, and look for incremental financing (including, potentially, some sort of exchange offer for the remaining convertible debt). Incremental proceeds from the Westwood agreement now can add a bit more breathing room, instead of having to supply all of the capital required (something which simply may not be possible).

What Do Redemptions Look Like?

But there’s a pretty large catch here: Arrival only gets the proposed cash if Kensington Capital V shareholders don’t redeem their shares before the merger. Those shareholders can simply ask the SPAC for their money back (plus interest) instead of rolling their equity into post-merger Arrival.

Amid the SPAC bust, high redemption rates have become the norm. In 2022, according to law firm Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer, on average more than 80% of SPAC shareholders redeemed their shares. (The figure was ~40% in 2021.) 2023 trends don’t appear any better than last year’s, with several de-SPACs seeing redemptions over 90%.

Meanwhile, Arrival is not the first public company to go the de-SPAC route. In October, biotech Coeptis Therapeutics (COEP), then traded on the pink sheets, agreed to merge with SPAC Bull Horn Holdings. The merger closed in October; 88.5% of Bull Horn shares were redeemed. COEP closed Thursday at $1.34.

In January, Wejo (WEJO) agreed to merge with TKB Critical Technologies 1 (USCT). That merger hasn’t closed yet, but with the redemption deadline passed it looks like redemptions were right at 50%. (TKB announced it would retain $56.7 million in its trust account; the SPAC had 11.2 million shares outstanding on March 29.) WEJO closed Monday at 40 cents.

It’s certainly possible that shareholders in KCGI will act the same way, and redeem their shares rather than roll equity into Arrival. That’s doubly true because the same vicious circle problem that dogs ARVL on the public markets exists in the de-SPAC transaction. A high redemption rate here means the company gets relatively little cash, and thus leaves Arrival largely back where it started, with an at best narrow path to survival. And so if more investors expect redemptions, more investors will redeem, and the vicious cycle begins anew and Arrival is on a straight path to Chapter 11.

Obviously, both Arrival and Kensington Capital V are aware of this problem. And so the deal clearly appears structured to minimize redemptions. The merger is notably different from the standard structure, in which SPAC shareholders receive a predetermined ownership stake in the post-merger company at a $10 per share price. Here, KCGI shareholders receive floating consideration: a number of shares equal to $17 divided by the volume weighted average price of ARVL stock in the 10 trading days prior to the fourth day before the Kensington shareholder meeting (the meeting at which the deal will be ratified or rejected by KCGI shareholders).

In other words, at the current price Kensington Capital V shareholders who don’t redeem get Arrival stock at a 38% discount (paying $10.48 for $17 worth of ARVL stock) to the average trading price leading up to the merger. There’s a one-year lockup for the sponsor as well.

Thinking Through Post-Merger Trading Dynamics

On paper, there’s thus an easy way to make a healthy, guaranteed spread. A trader can buy a share of KCGI for $10.48, which is equivalent to 121 ARVL shares. (Arrival will execute a 1-for-50 reverse stock split presumably before the merger, but we’ll use the current stock price for this example.) She can then short 121 ARVL shares for proceeds of $16.94. When the merger closes, our trader delivers to 121 ARVL shares and, even with a high teens annualized borrow rate, makes ~$6 per share on a seemingly easy arbitrage trade.

Here too however, there are some catches. The first is that there simply aren’t enough shares to go around. At full redemption, there will be nearly six times as many Arrival shares going to KCGI shareholders as there are currently existing Arrival shares. Not all of those shares are available to short, either. Per fintel, 10 million shares are currently available for borrow. Accounting for the reverse split, that availability presumably drops to ~200,000. At full redemption, KCGI shareholders are receiving 70 million shares (again, adjusted for the reverse split) in the merger. As a result, very few traders will be able to effectively arb out KCGI and ARVL.

Presumably, an investor could simply buy KCGI and then sell ARVL post-merger. But the problem here is that, in a full-redemption scenario, there is going to be an absolute flood of supply on the day this merger closes. And there simply isn’t enough demand for the $400 million-plus in equity value that is going to be unlocked upon the close. If that kind of demand existed, ARVL wouldn’t be trading at 14 cents with a current market cap under $100 million.

Bloomberg summed up the problem well on Monday, while quoting Julian Klymochko, CEO of Accelerate Financial Technologies:

So an investor who can short enough Arrival stock, would lock in the value and earn a spread on Kensington shares. But the bet is rife with risk, and history is not on the side of investors, according to Klymochko. Similar situations typically burn arbitrage traders because when “the 10-day VWAP period shows up, there’s no borrow, and arbs get loaded with stock and pile out at the same time,” he said.

Again, on paper there’s easy money to be made. In practice, professional arbitrageurs may well pass on owning ARVL at a massive discount through KCGI. The inability to borrow enough stock leads anyone looking to flip KCGI post-merger in a precarious position: needing to get out immediately once the merger closes. The VWAP leading up to the merger thus is likely to be higher than the ARVL stock price after the merger. The value of added shares acquired through the SPAC may be offset by a sharply lower price immediately after merger close.

Arrival With Cash

All told, it’s highly unlikely that Arrival gets the nearly $600 million ($300 million from Westwood, $283 million from Kensington) it’s hoping for. It’s possible it gets nowhere close.

To be fair, Arrival should get some cash. There’s a runway here to extend the runway to at least late 2024, when production is scheduled to begin. If Arrival can start producing vans, that in turn can create some enthusiasm to allow Arrival to raise more capital and keep the company solvent through 2025.

But even that outcome doesn’t look hugely attractive. Let’s imagine a scenario in which the SPAC merger sees minimal redemptions, and Arrival raises another $100 million at $0.20 (adding 500 million to the share count, and for now ignoring the effects of the split).

That gets the pro forma share count to 5.5 billion, or 110 million post-reverse split. Cash at the beginning of 2025 is likely relatively minimal; net cash is almost certainly negative with ~$200 million in convertibles still outstanding.

At that point, Arrival (currently trading at $7 pro forma for the reverse split) would need to have a market cap near ~$800 million, and an enterprise value near $1 billion, simply to support the current ARVL stock price.

That’s possible certainly. It’s not guaranteed. Arrival in late 2020 was a company that, per the presentation for its first SPAC merger, was “revolutionizing the electric vehicle industry.” It planned to have four models on the market in 2023, including an electric bus, two van models, and a “small vehicle platform”. Its “game changing microfactories [would] enable flexible low capex [capital expenditures] production.” It had $1.2 billion in orders from United Parcel Service (UPS).

Incredibly, Arrival projected that in 2024 it would generate $14 billion in revenue, and EBITDA of more than $3 billion:

Arrival SPAC merger presentation, November 2020

Now Arrival is operating a single factory that hopefully, if all goes well, will start producing a single model in late 2024, with the very real possibility that production (as has been the case for so many EV manufacturers, Arrival included) gets delayed beyond that point.

This Seems Too Hard

It’s exceptionally difficult to see that business worth $1 billion, which is what is required to see material upside in Arrival stock from this point. In theory, Arrival could get the XL into profitable production, raise more capital, and over time begin to build out a business plan that echoes the one that drove so much optimism two and a half years ago.

In practice, however, the path is simply so narrow. Bear in mind that Arrival’s two financing efforts imply the sale of ~85% of the company. No matter how the deal is structured, selling that much equity is a Herculean task. And even assuming the company can pull that off, it then has to actually produce vans that create sales, manage growth off a base from zero, and likely have to raise more capital at some point in the not-too-distant future.

There are simply so many points of failure along the way. And with current cash not even getting Arrival to the end of the year, there’s simply zero margin for error. Arrival gets credit for creativity, but at this point no amount of creativity seems like enough.

Editor’s Note: This article covers one or more microcap stocks. Please be aware of the risks associated with these stocks.

Analyst’s Disclosure: I/we have no stock, option or similar derivative position in any of the companies mentioned, and no plans to initiate any such positions within the next 72 hours. I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it (other than from Seeking Alpha). I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.

Seeking Alpha’s Disclosure: Past performance is no guarantee of future results. No recommendation or advice is being given as to whether any investment is suitable for a particular investor. Any views or opinions expressed above may not reflect those of Seeking Alpha as a whole. Seeking Alpha is not a licensed securities dealer, broker or US investment adviser or investment bank. Our analysts are third party authors that include both professional investors and individual investors who may not be licensed or certified by any institute or regulatory body.