Summary:

- The overall decline in bank deposits should continue as interest rates and inflation remain elevated.

- Bank of America and Wells Fargo have seen the most significant relative decline in deposits over the past year of the largest ten US banks.

- Bank of America and Wells Fargo are the largest owners of agency mortgage-backed securities, the primary culprit behind the “unrealized loss” scandal.

- Wells Fargo and Bank of America would need to decline by ~43% and ~66%, respectively, to be at the fair value of their common net equity position today after accounting for unrealized losses.

- If a recession causes default rates to rise, I do not believe WFC and BAC have sufficient capitalization for their common equity to weather the storm without significant external aid, such as a bailout.

alexsl

The crisis amongst regional banks has led to a substantial devaluation of virtually all US banking stocks. The broad US bank ETF (KBE) has lost around 35% of its value since February, while the regional bank ETF (KRE) has declined by about 43% since then. Subsequently, most US banks are trading near or below their tangible book value and at very low “P/E” ratios, usually around 5-9X or less half that of the S&P 500 as a whole. That said, their risk profile remains high due to the significant unrealized losses on many banks’ fixed-rate bond security positions.

As detailed in my bearish view regarding the regional bank ETF KRE “KRE: The Banking Crisis Has Slowed, But It Cannot Be Stopped” (published before the most recent decline), I believe investors should not underestimate the magnitude of this risk factor. Accounting for the market value of bank assets (which fell substantially as rates rose last year), after unrealized losses, the market value of total US bank equity was around 80% below most banks’ “GAAP” book value. While that may seem extreme, we must keep in mind that banks have, in total, ~$22.9T in assets and ~$22.6T in liabilities, so a small devaluation in assets could easily wipe out most of the equity value (assets minus liabilities). Further, that comes before preferred stock, which usually makes up ~1-2% of a bank’s assets (or 10-20% of equity), meaning a complete liquidation of most banks today would likely leave very little for common stock equity investors.

If the economy were strong, loan loss risk was minimal, and deposits were growing (usually the case), this factor would not necessarily be an issue. Banks can effectively count on the US Treasury (and other bond-sellers) to repay their debt by maturity, so banks would not realize any losses on these securities positions if held to maturity. However, because deposit levels are falling faster in recent history, banks are being forced to sell these securities at significant losses, causing rapid deterioration of bank “equity.” As long as interest rates are relatively high and the Federal Reserve pursues its soft “QT” program, total bank deposits will likely continue to decline, meaning this issue will likely continue to grow. For now, banks are benefiting from a low default environment. Still, if a recession triggers a rise in defaults, I expect this issue will become much more significant as bank assets devalue further. Finally, as deposits decline, banks see deposit rates grow, causing net interest margins to slip and potentially causing EPS levels to reverse quickly.

Some banks, such as JPMorgan (JPM), appear to be net benefactors of this issue as the highly solvent bank (comparatively) scoops up assets from failing banks at a discount. However, not all large banks appear to be completely safe. Two notable examples of large banks with potentially high-risk profiles are the popular Wells Fargo (NYSE:WFC) and the Bank of America (NYSE:BAC). Of course, before we discuss WFC and BAC specifically, we must consider the broader monetary environment that is creating growing pressure on the banking system.

Understanding The Cause of “Deposit Flight”

The primary immediate issue facing most US banks today is the broad decline in bank deposits. Historically, banks have been able to count on nearly endless deposit growth, particularly over the “great moderation” period of the 1980s-2007, wherein the Federal Reserve had managed to keep inflation in line while the economy grew at a steady pace, benefiting from globalization and related technological advancements. This trend has allowed banks to take on more significant liquidity risks because deposits will always catch up to loans (and securities positions), as most lent money returns to banks’ vaults (as borrowers deposit borrowed money).

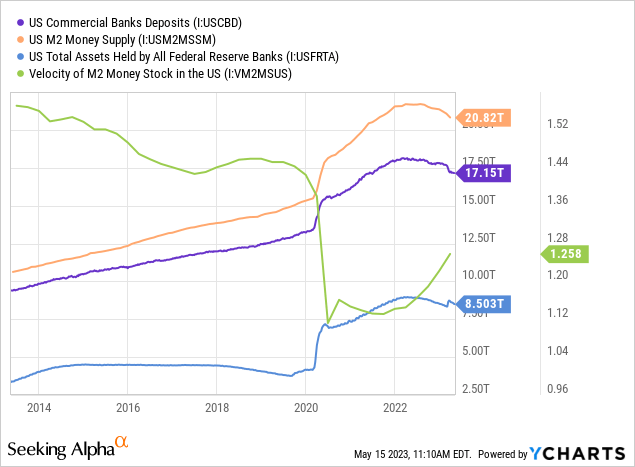

Since 2008, inflation, GDP growth, and most related macroeconomic measures have become far more volatile and increasingly dependent on QE, extreme interest rate changes (either near-zero or very high as in today), and other less moderate changes. More recently, the shift to QT (or the slow “deletion” of money from the economy via “balance sheet run-off“), rise in interest rates, and a sharp increase in inflation have reversed the trend on deposits and the M2 money supply. The economy is also seeing a substantial relative increase in the velocity of money, a statistic that has declined consistently for multiple decades. See below:

The sharp increase in the velocity of money is notable, meaning one dollar is changing hands more rapidly than before. Instead of money being lent by banks only to end up back in bank deposits by the borrower, it is circulating through the economy. This is not due to increased economic activity. Still, a sharp increase in consumer and producer price inflation forces many people and businesses to slowly withdraw savings to pay for increasingly costly goods and services. For now, this trend is relatively gentle and new. Still, it is already creating havoc for some banks as those with falling deposits must sell assets in an increasingly illiquid environment.

To simplify, the current monetary dynamic is virtually the opposite of that seen in 2021, wherein banks had “too much” liquidity amid a surge in new cash created via QE. I suspect this dynamic will continue until a sizeable dovish pivot occurs that causes a stabilization in the money supply; however, that would also require a more considerable moderation in inflation to arrest the trend totally (see the velocity of money). Reducing short-term interest rates could lower the pressure on bank deposit rates (which are starting to compress NIMs); however, significant rate cuts would likely not halt unrealized securities losses since those are mainly tied to long-term securities. Finally, a sizeable dovish pivot with low inflation would probably require a recession, increasing bank loan losses. Thus, without the Federal Reserve risking re-accelerating inflation, there is seemingly no way to “save” most at-risk banks.

Deposits Flee Wells Fargo and Bank of America

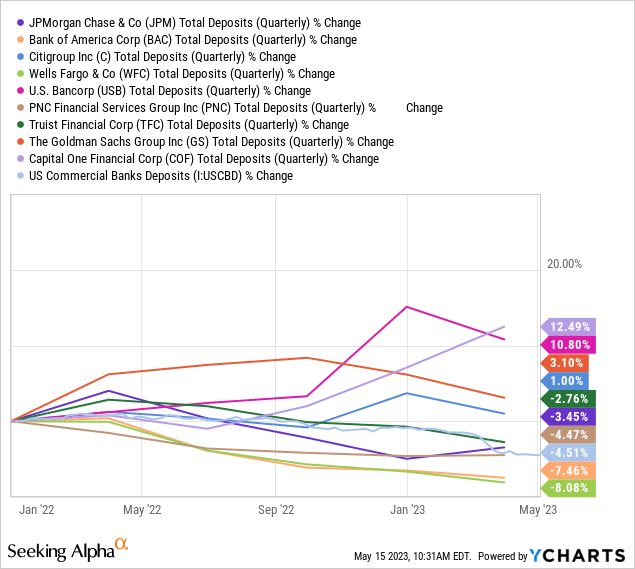

Among the most significant ten banks in the US, virtually all have fared far better than the smaller regional banks. However, among the top ten, Wells Fargo has faced the most rapid decline in deposits since the deposit peak around early 2022. WFC’s deposits have declined by 8% since then, or around $130B, the largest deposit drawdown in the bank’s history. Bank of America has seen similar declines in total deposits, ranking at the bottom of this list. See below:

As discussed in Wells Fargo’s last quarterly presentation, the bank’s total loans rose last year while deposits declined, predominantly due to consumer outflows as “customers migrated to higher-yielding alternatives.” As total bank deposits fall and savings account rates begin to rise toward the discount rate, all banks will need to weigh losing deposits against harming their net interest margin via higher savings account rates. Wells Fargo’s rates remain below that found on most online banks, meaning its depositor outflow is likely continuing or even accelerating today. Additionally, Wells Fargo specifically may still be facing some issues due to the series of scandals that harmed the bank’s brand in the late 2010s. That said, BAC and WFC face similar risks as customers shift away from the most prominent “traditional” banks toward lean online alternatives with much higher savings yields.

What are WFC and BAC Worth Today?

Wells Fargo and Bank of America are the largest owners of US mortgage-backed securities due to their acquisitions of failed mortgage banks after the 2008 recession. These assets are critical for assessing risk because they’re predominately fixed-rate with 15-30 year maturities, giving them immense duration-risk-related losses over the past year as mortgage rates rise. At the end of last quarter, Wells Fargo’s total debt securities were $511B, or 38% of its total deposits and 27% of its assets. This can be compared to $851B, or 44% of deposits and 27% of assets for Bank of America. At the end of Q1, WFC had $245B (18% of deposits) in agency mortgage-backed securities, while BAC had $411B (21% of deposits). Both banks have massive exposure to the MBS market, the key culprit behind the recent declines in bank valuations.

As of March 31st, the total difference between Wells Fargo’s total debt securities amortized cost ($429B) and the fair value of those securities ($385B) was $44B. $31B of those unrealized losses came from agency mortgage-backed securities positions (see 10-q pg. 65). Accordingly, WFC’s equity NAV is likely around $82B or its tangible book value of $126B minus $44B in unrealized losses. Importantly, this “fair-value” measure of WFC’s common equity is only 4.3% of its total assets today, meaning a relatively small devaluation in WFC’s assets could wipe out all of WFC’s remaining equity value.

Bank of America’s position is similar, with its total debt securities at amortized cost of $801B, compared to a fair value of $698B, or a $103B difference (10-Q pg. 57). Similarly, over 80% of those losses are due to devaluation of MBS positions. With a tangible book value of $183B, Bank of America’s more accurate fair value of common equity is likely closer to $79B, or just 2.4% of assets. By this measure, Bank of America is riskier than Wells Fargo; however, both are far worse than the other largest banks, such as JPM and Citigroup (C).

Among the top ten banks, the only one that is much worse than BAC and WFC is Truist Bank (TFC), with a staggering $19.9B unrealized loss or 91% of its tangible book value. As detailed two months ago in “Truist: Immense Unrealized Bond Losses Threaten Core Equity Stability,” Truist is likely the riskiest of the top-ten banks based on equity devaluation; however, its deposits are more stable than BAC and WFC’s. Further, BAC and WFC are much larger systemic risk factors due to their size and dominance of the US debt securities market.

The Bottom Line

Considering the negative trend in deposits and the very low net “fair value” common equity value of BAC and WFC, I would not buy them for a penny above their market net asset value. For WFC, that is $82B or 43% below its current price, equating to a price target of ~$22.9. For BAC, that is $79B or 66% below its current price, equating to a $10.2 price target. In other words, I am very bearish on both BAC and WFC and believe they’re significantly overvalued today despite their low “P/E” ratios (both with forward “P/E”s of ~7.9X today).

In my view, most US banks’ “P/E” and dividend yields are inconsequential today because potential bank losses due to asset devaluation can easily be 10X larger than potential bank incomes during strenuous periods. Fundamentally, due to significant leverage, bank equities often “rise like an escalator but fall like an elevator,” or they perform well consistently in good economic periods but suffer considerable losses in poor periods. This pattern has expanded over the past two decades due to banks’ (and the economy’s) substantially increased reliance on Federal Reserve stimulus. I discussed this concept before the recent banking crash, which was proven true over recent months.

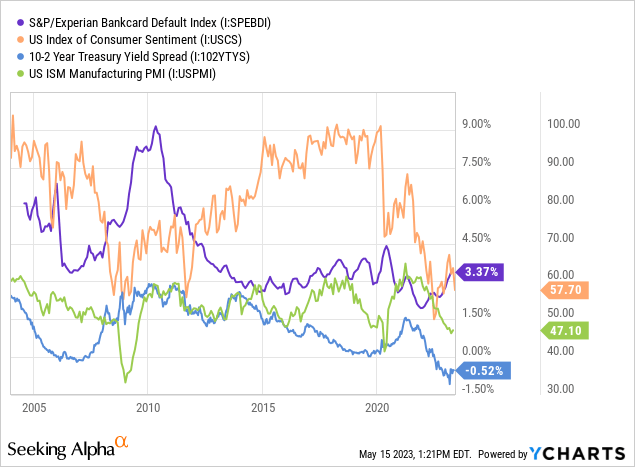

In my view, it is generally unlikely BAC and WFC recoup losses on assets as falling deposit levels will push them to sell more securities positions at losses. I suspect deposit levels will continue declining as long as QE policy does not return, which I suspect will not be due to the persistence of core inflation. Further, both banks could suffer much more significant losses should default rates increase. We should remember that banks are already struggling amid a prolonged period of below-average defaults, so their fair equity values could easily fall below zero if defaults rise. In my view, the current macroeconomic outlook indicates this, as seen in low consumer confidence, a “contracting” manufacturing PMI, and record yield-curve inversion. See below:

The consumer bankcard default index has now risen back to historically normal levels amid the increase in economic strains. Of course, as households and companies face higher costs and slower income growth, deposit declines may accelerate as savings are utilized. Crucially, the unemployment rate is rising five times faster for “higher income” households, which comprise a much more significant portion of total personal savings. As layoffs rise amid growing recessionary signals, I suspect WFC and BAC will face a more rapid decline in deposits and a more significant increase in defaults.

If so, the survival of WFC and BAC’s common equity would depend on a government bailout or similar. If it were not for that possibility, I would consider short-selling the stocks; however, because BAC and WFC are certainly “too big to fail” banks, I would avoid short-selling them due to the volatility that will come from such speculations. That said, I believe they’re both overvalued, with Bank of America being the most overvalued of the two. Further, even if they decline significantly, I would not buy the stocks in speculation of a bailout because I do not believe the Federal Reserve could create sufficient new money to do so in the current inflationary environment (considering the nearly $2T “unrealized loss” burden today).

Analyst’s Disclosure: I/we have no stock, option or similar derivative position in any of the companies mentioned, and no plans to initiate any such positions within the next 72 hours. I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it (other than from Seeking Alpha). I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.

Seeking Alpha’s Disclosure: Past performance is no guarantee of future results. No recommendation or advice is being given as to whether any investment is suitable for a particular investor. Any views or opinions expressed above may not reflect those of Seeking Alpha as a whole. Seeking Alpha is not a licensed securities dealer, broker or US investment adviser or investment bank. Our analysts are third party authors that include both professional investors and individual investors who may not be licensed or certified by any institute or regulatory body.