Summary:

- One reason it might make sense to pay up for shares of artificial intelligence companies is as insurance against their technology taking your job.

- The impact of AI on white collar work next decade may resemble the impact outsourcing to China had on blue collar work this century.

- That said, the best investment in the China outsourcing theme wasn’t in Chinese manufacturers, but rather in companies like Walmart that used that outsourcing.

- Similarly, I find Nvidia Corporation shares obscenely overvalued relative to those of, say, a midcap health insurer who might better benefit from AI.

- I hope this article inspires you to consider not only the valuation of AI-related stocks, but also the economic future of your job.

PhonlamaiPhoto

In my view, THE main reason to own investments in artificial intelligence (AI) is as a form of insurance against it replacing your job. As someone who mostly focuses on non-U.S. dividend stocks, this “insurance” angle is my main motivation for focusing on this theme, which is mostly U.S. and mostly made up of stocks that pay little or no dividends. While the idea of replacing your earned income simply by owning a share in the robot that may one day take your job has many flaws, it presents a set of scenarios many white-collar desk workers should at least think through when deciding on investment allocations.

A good starting point for this thought exercise is the largest U.S.-listed AI exchange-traded fund, or ETF, the Global X Robotics & Artificial Intelligence ETF (NASDAQ:BOTZ). The largest holding in BOTZ is NVIDIA Corporation (NASDAQ:NVDA), whose stock made news this year on reaching a market valuation of $1 trillion, likely driven by expectations of its role in developing AI and its applications. When asked what future scenario might justify a $1 trillion valuation for NVDA, my “back of envelope” estimate was to assume its technology can eventually replace the work of 1 billion white collar workers within 10 years, and then NVDA manages to monetize $1,000/year per worker it replaces over the following 10 years.

While those are very rough and round numbers in an idealized scenario, that scenario should at least provide a baseline from which we can value and assess risks of different AI scenarios on both our job prospects and our investments. This article will start by looking at a definition of AI that is meaningful to workers and investors, considering its impacts at both a microeconomic and macroeconomic level, then considering these impacts on NVDA specifically, and to BOTZ more broadly.

What is Artificial Intelligence?

BOTZ’s name references both robotics and AI, and in broad terms, I tend to see robotics as technologies which can replace blue collar jobs, while AI makes me think of technologies that might replace white collar jobs.

In other words, when I say “robots,” I am usually talking about physical machines that do physical work, ranging from small ones that automatically clean the floor of your home, to the larger ones on the assembly lines of car factories. When looking at almost any robot, I often consider what kind of human labor it replaces, and in some cases, what other benefits and risks the robot introduces beyond just replacing human labor. For example, the robots that sweep our floors saves probably saves my family about an hour of housework each week. On the other hand, robots in a car factory can be seen as replacing several expensive workers, but may perhaps be better seen as making one worker far more productive and reliable than a team of several workers assembling cars without robots.

In at least these example scenarios, the robots have taken away work that most of us are least interested in doing ourselves, or in having our children and grandchildren continue spending time on. One example I often use is the modern elevator, where pushing a button to get us to the floor we want to go to long ago replaced human elevator operators, and I’ve never met anyone who regrets their children will never have the opportunity to work as an elevator operator.

As is often said, many robots specialize in work that is either dull, dirty, dangerous, or very detailed. Unlike factory robots or elevators, my vacuum cleaner at least needs to be able to figure out how to get around a chair that might have moved since the previous cleaning, which starts to require a little more programming logic, but is still only the smallest step in the direction of what any of us might call AI.

As the ticker “BOTZ” implies, we also often use the term “bots” in daily language to refer to machines that do no physical work, but rather only process information. At the very simple end, I think of tools like Calendly, which replaces some work of a secretary that might make appointments for me, though this is still at the level of a simple software program that doesn’t really need to think, learn, or respond like a human. When many readers in 2023 think of AI, were are more likely to think of bots like ChatGPT, which can understand natural language questions and potentially generate written answers that might replace much of the work many readers of this article might spend hours doing each week. For example, when I asked ChatGPT to write me an explanation of how NVDA might become worth $2 trillion within 5 years, this is the answer it gave me. It didn’t exactly answer my questions with any of the numbers I was looking for, nor is it likely to fully replace any Seeking Alpha analysts writing about NVDA anytime soon, but it does show some potential as a tool helping with some of the more tedious parts of our research and writing.

Quite simply, while simpler Internet tools may have already replaced a significant amount of work done by executive assistants and travel agents, ChatGPT hints that more intelligent software may soon be able to do much of the work of research assistants, copywriters, accountants, and perhaps many of the other professions of readers of this article. At this point in my thought experiment, I might imagine that NVDA might be to AI what the electric motor is to physical robots in the previous paragraph, and clearly, having a monopoly on making electric motors that go into robots would have been very valuable.

Key Metric: Revenue Per Job Replaced

Back to my “back of envelope” valuation of NVDA. If we are to think of this company as a likely backbone of AI, my preferred metric would be something like “revenue per job replaced.” Even though many readers here, and perhaps even ChatGPT itself, could better estimate how many and what kind of jobs NVDA-enabled AI might replace, this framework at least helps keep us focused on AI’s value proposition: replacing human workers. NVDA itself may not make or monetize the whole of a given AI solution, but if that solution is something a user will pay $3,000/year for because it replaces a $30,000/year worker, and NVDA can capture 1/3 of that revenue, then $1,000/year would be NVDA’s revenue per job replaced. This changes my view of NVDA as just another chip maker to a maker of labor replacement components, and so moves my valuation framework for it from the semiconductor market to the labor market.

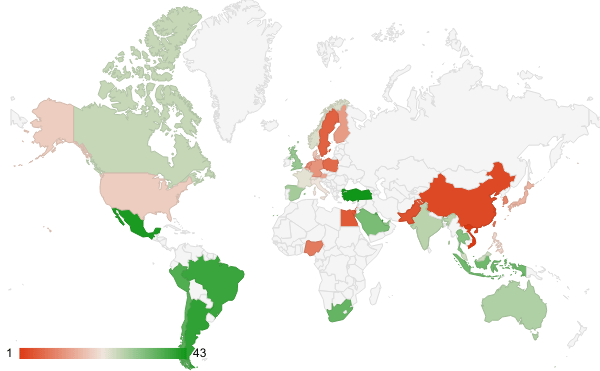

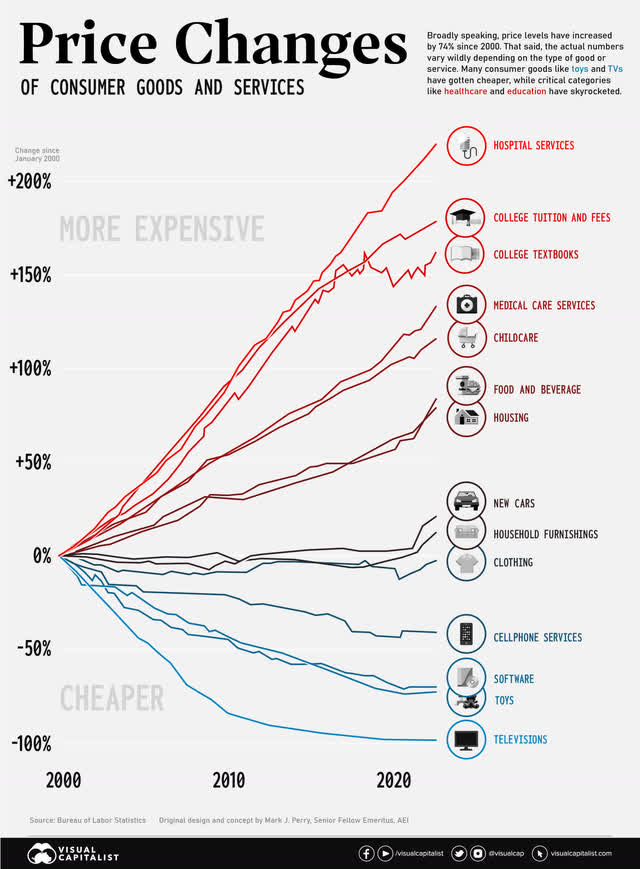

BOTZ’s 5th largest holding, a 7% position in Japanese factory robot maker Fanuc Corporation (OTCPK:FANUY), is a company which I have already been thinking about this way since the day I bought it many years ago. The below chart form Fanuc’s own website shows a cumulative number of robots made by this company, and its growth from only around 50,000 robots in 1995 to 760,000 robots in 2021. The EU version of Fanuc’s website has a feature called the “Robot Finder,” where you can find which of Fanuc’s many robots can replace the job you are looking for, starting with welders. It is then relatively easy, for me at least, to see how sales of these worker-replacing robots add up to Fanuc’s JPY 850 billion (USD 6.5 billion) in sales last year.

I would see the “best case scenario” for NVDA over the next 30 years if it replaces as many writing and accounting jobs as Fanuc has replaced welding jobs. BOTZ’s 2nd largest holding is Intuitive Surgical, Inc. (ISRG), who makes robots that, instead of welding, help with small and precise surgeries. To justify an >$1 trillion valuation for NVDA, I almost have to assume that both FANUY and ISRG become two of NVDA’s customers, where NVDA makes their robots smarter and able to replace even more advanced workers. That in turn reminds me of a company whose name evokes the word intelligence, Intel Corporation (INTC), back when Apple (AAPL) decided to use its chips to make its computers better for a few years, before Apple eventually replaced Intel chips with their own. Those highly uncertain possibilities, and my view that NVDA needs to get so much right to capture trillions of dollars’ worth of worker replacement market share, are why I think NVDA shares are extremely overvalued.

Macro Impacts: Is AI Deflationary?

On a microeconomic level, being able to replace a $30,000/year worker with a $3,000 robot is a clear cost savings, an almost no-brainer business decision to make your business more profitable and reliable. When thousands of employers start making that same decision, then we need to start thinking about the macroeconomic impacts of lower production costs, disappearing jobs, and lower wages. Labor-saving technologies in general tend to be deflationary, sometimes even hyper-deflationary, with the most fundamental example being how much more expensive food was back when 90% of humanity had to work in subsistence farming to produce that food. My own business runs today at the prices I can offer in large thanks to my being able to do with platforms like Amazon (AMZN) web services and tools like Calendly what once would have required an IT person and an executive assistant.

More recently, I have made increasing use of Google Translate and Deepl, which have already saved me tens of thousands of dollars I would have otherwise spent hiring translators or translation services. Looking purely at the supply side, AI seems likely to flood the labor market and push down the costs of tasks like writing, translation, and interpreting x-rays. If demand were to remain constant, such an increase in the supply of services by technology that doesn’t take vacation or require health insurance could be very deflationary on an economy of which such services make up a huge percentage.

Of course, demand is almost certainly not going to remain constant with a deluge of low-cost and reliable replacements for many services. Just as we saw with the goods economy, innovations that bring down the cost of a good often tend to greatly increase the demand for that good, as seen with goods ranging from the Model T to the flat-screen TV. This new demand driven by lower prices can be called “induced demand,” which often refers to how traffic increases after a toll-free road is made wider, but is also seen with low-cost airline routes, video calls, and other for-fee services whose providers we can buy shares in.

Back to my need for language services, I currently have no demand for a $2,000 human private tutor to improve my French, and have found the $100-200 simple app-based lessons like Duolingo lacking and uninspiring. On the other hand, if I could find a $200-400 AI-driven French course which is as almost as good as a human private tutor, but could help me talk about obscure topics that interest me and never lose patience with my mistakes and questions, then I’d subscribe to that service tomorrow. I can easily imagine thousands of services in our economy where AI could provide a lower cost and more reliable, even if not as creative or flexible, replacement for humans that are currently too expensive for most users.

In order for me to weave this into an NVDA bull case, though, I would have to have a better idea for how much of the $200-400 of my French course would flow to NVDA revenue, just as I used to model how much of my wife’s Dropbox subscription fee went to Amazon AWS revenue, back when Dropbox was on AWS.

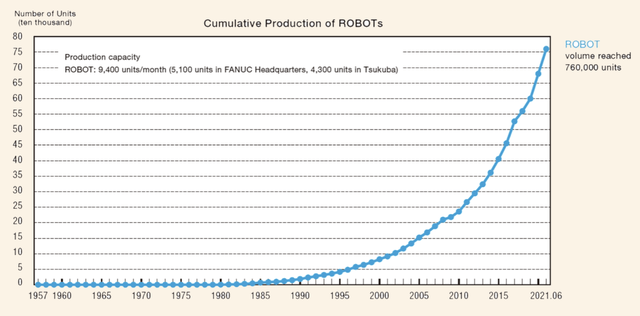

From a macroeconomic point of view, it is worth remembering that most of the inflation in the U.S. is due to the rising costs of services, especially skilled services like higher education and medical care. As the chart below from Visual Capitalist shows, the costs of many goods, with the exception of college textbooks, have either declined or risen more slowly than the cost of food and housing, while medical and higher educational services seem to be the ones whose costs have most outpaced inflation. If AI is able to replace much of the administrative work done by hospitals and universities, and in doing so make the price of these services decline like the prices of televisions, then demand may increase, but more likely than not, it means the overall level of consumer prices is still likely to decrease.

Bringing this back to the title question of this article: how can we know if AI will replace our job versus making our work more productive and in demand, and would investing in NVDA help hedge against NVDA technology suppressing our wages? To help answer that, the next section compares American outsourcing of services to AI over the next two decades to American outsourcing of good manufacturing to China over the past two decades.

AI Services 2030 vs. China Manufacturing 2010

Rather than try and guess the different ways NVDA might monetize replacing service jobs over the next two decades, I find it more helpful to try and use an example from history to draw parallels on how our jobs and investments might evolve over the next decade. That big and recent example I am of course thinking of has been the replacement of U.S. manufacturing by lower cost Asian manufacturing, some to Fanuc’s robots, but more much cheaper human factory workers in China. Chinese factories manufactured many of those televisions, toys, cell phones, clothes, furnishings and car components in the above inflation chart, in a way that it would be very difficult to argue that deflation in goods prices to the U.S. consumer wasn’t largely due to China.

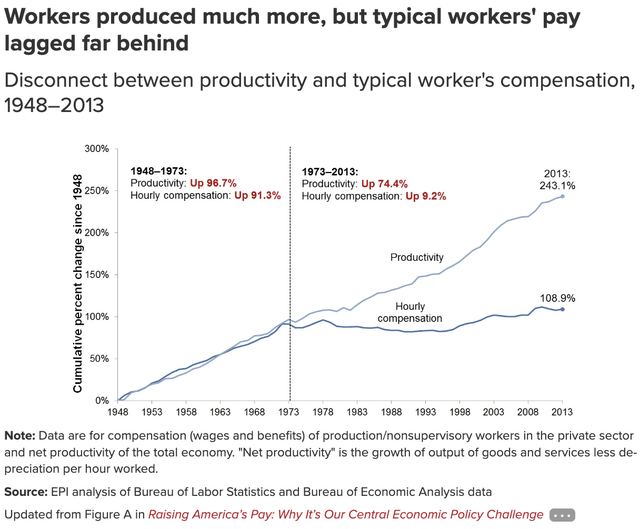

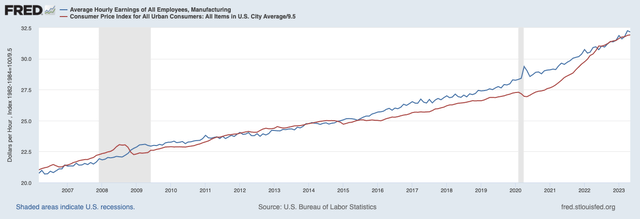

While that probably meant many of us bought a few more TVs and toys than we otherwise might have bought if those products were still American-made and more expensive, what it also meant is that those of us working in the service sector saved money on goods that we could instead spend on services. On the income side, this probably had the most negative impact on the wages of American workers in manufacturing, which have barely kept pace with inflation since 2006, at least according to the below chart from the St Louis Federal Reserve.

St Louis Federal Reserve (FRED)

Despite narratives about the decline of American manufacturing leading to the rise of Trump, it seems wages have at least kept pace with inflation despite this outsources, but this next chart from the Economic Policy Institute provides shows a key factor that might explain this: rising productivity. In other words, U.S. manufacturing wages may have only been able to keep up with inflation because American manufacturing has gotten almost 2.5x as productive over the 1970s-1990s when competition was coming from Japan, then since 2000 with more competition coming from China. Similarly, workers in service jobs like writing, answering the phone, or administering hospitals or universities, may only see their wages keep up with inflation over the coming decades if AI similarly increases the productivity of their work.

Given this framework of outsourcing being the force that reduced U.S. goods inflation, reduced the growth in manufacturing wages, and perhaps drove increased productivity, I wish to use a similar outsourcing framework to think of AI. In this case, I will think of AI services of being citizens of a foreign country to which we may be outsourcing some of these service jobs, and NVDA just happens to be one big leading “automaker” in this new foreign country. I will sometimes refer to that fictional country and trading partner as “The Republic of AI”, since I doubt any one company, even NVDA, can dominate that economy long enough for me to consider it a kingdom. That framework links to the China theme when I see stories like ByteDance ordering $1 billion of NVDA chips so far this year, which at least starts to put a number on how much the AI algorithm in TikTok might be getting monetized by NVDA this year.

To get an idea of how significant AI’s impact on the service sector might be compared with China’s impact on the manufacturing sector, consider that services make up over 45% of the U.S.’s $23 trillion GDP, while goods consumption makes up only about half that. It is also important to remember that the U.S. is still a net exporter of around $240 billion in services per year, versus being a net importer of around $1 trillion per year in goods. In 2022, China made up about $380 billion of that $1 trillion trade deficit in goods, and so I am similarly interested in projecting what America’s future “trade deficit” in services with “The Republic of AI.” Of the roughly $10 trillion per year U.S. consumers currently spend on services, many of those services like haircuts and nursing will take much longer to replace with AI, but my back of envelope $1 trillion/year in AI spend starting 30 years from now is about in line with 10% of current U.S. services GDP. While it’s far from certain that AI will reach those levels, and even less certain that NVDA can capture the lion’s share of it, it remains a benchmark scenario for valuing investments in stocks like NVDA.

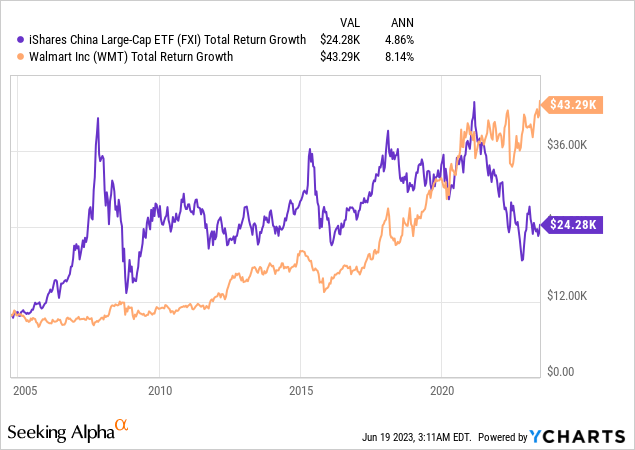

Back to tying economic scenarios with investments, perhaps the simplest picture of how difficult it is to be right about the winner in advance, even if you are right about how it will play out, is the chart below. This chart shows the total return from investing in the oldest U.S.-listed China ETF, the iShares China Large-Cap ETF (FXI), versus investing in an “old economy” U.S. company that happened to be really good at outsourcing to China, that company being Walmart Inc. (WMT). From the launch of FXI in 2004 to around 2007, FXI would have quadrupled your money in a few short years while WMT returned almost nothing. From that high point in 2007, investors in FXI would have had negative total returns for almost any period ending in the 15 1/2 years since, while shareholders in WMT would have quadrupled their money.

This is just one rough example of where I think investing in the customer-facing business that profitably uses outsourcing or AI is much better than investing in that diversified but replaceable supplier of outsourcing or AI. In other words, ByteDance might be in a better position as the one buying NVDA now, and possibly having the power to later do to NVDA what Apple did to Intel.

As a question of timing, I think it is more likely that NVDA’s current valuation puts it closer to where FXI was in 2006 or 2007 in the above chart than where it was in late 2004, so I don’t think we’ll need to wait as long as WMT did for smaller users of AI to outperform NVDA from current levels.

Political Risks of AI Investing

Since comparing AI to trade with China is almost certain to bring up comments about political risk, I wanted to briefly say that even investing in legally domestic AI companies is likely to have political risks as well, especially when we’re talking about trillions of dollars. NVDA’s current market cap is already over 4% of US GDP, or almost 100% of the GDP of a country like the Netherlands, Indonesia, or even Mexico. Outsourcing manufacturing jobs to China, in a way that likely limited the rise in factory wage increases to the rate of inflation, ultimately led to political demands to put tariffs on Chinese imports. If NVDA manages to become a $3-5 trillion company by making over $100 billion/year in profits by replacing 50-100 million service workers, you can be just as sure that the next trade war may take the form of a “windfall profits tax” or something like that on the technology companies taking those jobs.

I tend to be a bit more of an optimist about AI making service workers more productive, rather than simply putting them out of work or suppressing wages, but this political “heads the government wins, tails investors lose” scenario is one I can’t ignore for any trillion-dollar company threatening jobs. I see political risks being significantly lower for a midcap health insurer or online education provider who can use AI to become significantly more profitable, than for a company with the size and profile of NVDA.

Conclusion

I should note that my disclosure shows that I’m long NVDA, and that is purely due to a small position my son wanted to buy in his UTMA account a few years ago. He wanted to buy those shares with some of his gift money because he was interested in NVDA’s chip technology, and I have long encouraged my kids to own and spend time learning about individual companies. While this has helped his portfolio outperform mine on a price return basis so far this year, time will tell if he continues to outperform, or whether I’m right about NVDA being an overvalued name with too many scenarios making its value worth far less than $1 trillion.

It is also worth noting that NVDA has a bond due in 2040 that currently trades at a yield of 4.8%, indicating a fairly high level of confidence that NVDA is not likely to go bankrupt over the next 17 years. That 4.8% yield is coincidentally about the same as FXI’s average rate of total return over the past 19 years as China increasingly replaced U.S. manufacturing, but more than 100% of that return came in the first 3 of those 19 years. I similarly expect that much of the eventual return NVDA shareholders enjoy its AI solutions have likely been more than priced in by the near-quadrupling of NVDA’s stock price over the past 9 months, and so would be surprised if NVDA shares return more than its bonds over the next 17 years. Much of my pessimism has to do with the number of things that have to go right for NVDA to monetize trillions of dollars over the next 17 years, while only a few things have to go wrong for NVDA to fall back down to being a sub-$500 billion company.

Looking more broadly at the BOTZ ETF, my biggest problem with seeing it as a hedge against AI replacing white collar jobs is that NVDA is a very large component in it, and I would much rather own a smaller and more proven job replacer like FANUY than NVDA. BOTZ does have other notable holdings, for example ISRG, which might supplement or replace work in the expensive health care sector, but I would rather look at ISRG in its own right than have BOTZ mix it in with NVDA for me.

If I had to pick one ETF to better represent a more passive allocation to AI, it would probably be the ROBO Global Artificial Intelligence ETF (THNQ). THNQ also has NVDA as a top component, but only with a 2.6% weight, as THNQ seems to be aiming for more broadly diversified exposure. THNQ does not seem to own ISRG or FANUY, but does have positions in other smaller AI technology companies like MongoDB and C3.ai, smaller AI users like Shopify, and 2% positions in other giants like Amazon, Alphabet, and Microsoft. I am not sure if Shopify will benefit from AI the same way Walmart benefitted from outsourcing to China, but I at least I hope it is clear that I would rather own well-valued users of AI technology than an expensive maker of technologies whose economics still look quite speculative.

Editor’s Note: This article discusses one or more securities that do not trade on a major U.S. exchange. Please be aware of the risks associated with these stocks.

Analyst’s Disclosure: I/we have a beneficial long position in the shares of FANUY, NVDA either through stock ownership, options, or other derivatives. I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it (other than from Seeking Alpha). I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.

Seeking Alpha’s Disclosure: Past performance is no guarantee of future results. No recommendation or advice is being given as to whether any investment is suitable for a particular investor. Any views or opinions expressed above may not reflect those of Seeking Alpha as a whole. Seeking Alpha is not a licensed securities dealer, broker or US investment adviser or investment bank. Our analysts are third party authors that include both professional investors and individual investors who may not be licensed or certified by any institute or regulatory body.

Non-US markets cover 75% of the world’s economy, 90% of IMF expected GDP growth, and 95% of the world population. That’s most of my time and money is invested outside the US, where I have lived most of my life and find opportunities to share with you. See how to improve your international stock strategy with your free trial to The Expat Portfolio.