Summary:

- Snap’s ARPU as a percentage of Meta’s ARPU is actually higher in geographies ex-North America.

- Any weakness in the North American business may make life challenging for Meta.

- If chatbots can truly take off on messaging properties, Meta, which generates less than half of Google Service’s revenues, may end up gaining material market share from Google.

Derick Hudson

First some caveats: while we have all probably read Charlie Munger’s quote “I never allow myself to hold an opinion on anything that I don’t know the other side’s argument better than they do”, the reality is this is exceptionally uncommon and challenging. In fact, when investors mention risks about a company they like, they often deliberately choose strawman arguments from the other side and advertently or inadvertently ignore steelman arguments. I will try to avoid strawman bear cases (and boy there are many), and only outline the bear cases that indeed concern me as a shareholder. Since I am writing about the bear cases, they are known unknown, but obviously, there can be unknown unknowns that I may not even be aware of but can certainly affect Meta (NASDAQ:META) in the long run.

Before we get into those long-term concerns, let me start where I left off in last week’s post: Meta’s Moat. I have received quite a few insightful constructive feedback. One of the counterarguments was since the business of social media had dramatically changed over the last decade, it is less useful to track where newer social companies are today at a similar scale vs where Meta was a decade ago. While I did mention that “the business of social media likely changed forever”, I could have done a better job outlining where things stand today between Meta vs. other social companies. For the purpose of this piece, I will primarily focus on Snap (SNAP) to continue the conversation from the last week’s piece.

Let’s start with ARPU.

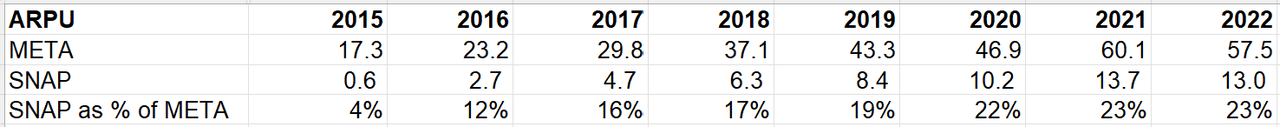

Back in October 2014, Snap launched its ads, so it was just ~4% of Meta’s ARPU (see how it is calculated below) in 2015. But then it quickly ramped up to 12% of Meta’s ARPU in 2016 and reached 22% in 2020. Then the progress stopped in the last couple of years. Zuckerberg and Spiegel initially had somewhat opposite tones when it comes to ATT; Spiegel almost welcomed Apple’s (AAPL) ATT but it is ATT that may have played a significant role in stalling their ARPU momentum against Meta.

Some may wonder whether user mix differentials between these two companies had contributed to the stalling of progress in ARPU. Not really; in fact, while Snap’s ARPU quickly ramped to ~8-9% of Meta’s by mid-2016, it hasn’t been able to gain much ARPU momentum in North America (NA) since then, and in recent quarters, it started going in the wrong direction.

What somewhat surprised me is that Snap’s ARPU as % of Meta’s ARPU is actually higher in geographies ex-North America. There are interesting implications here that are relevant to my first bear concern about Meta (to be discussed shortly).

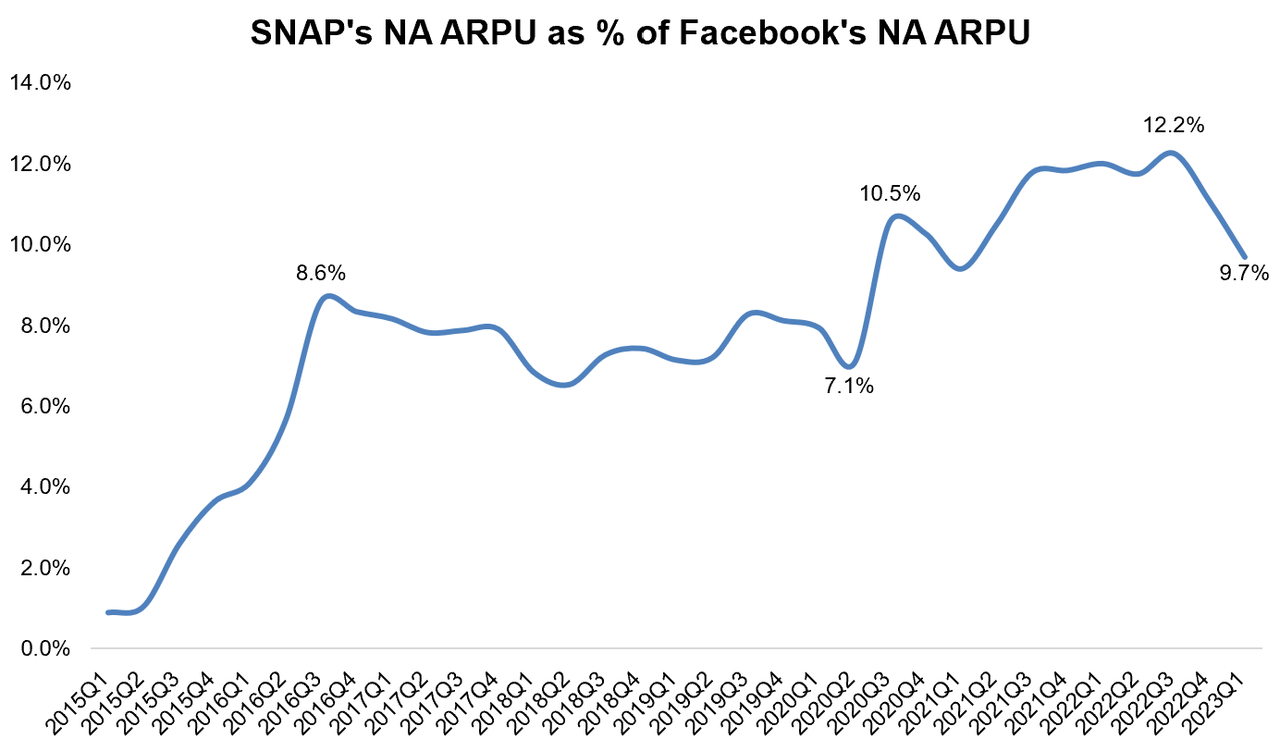

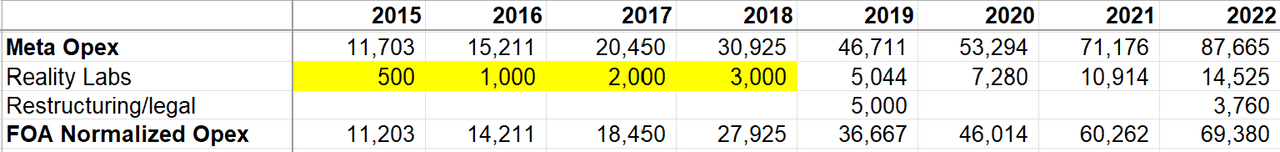

Let’s look at Opex now. To make it more apples-to-apples, we need to make some adjustments. Since we want to compare Snap to Meta’s FOA business, I have excluded Reality Labs (RL)-related opex. Since RL expenses were disclosed in 2019, I have made some assumptions for RL Opex in 2015-2018. I also excluded restructuring expenses for both Meta’s FOA segment and Snap in 2022 as well as Meta’s large legal bills in 2019. To be fair, Snap also invests in AR but since they don’t quite disclose it separately (and it seems very much part of the core business), I took Snap’s total Opex base (ex restructuring) for calculating their Opex per DAU (Note: Snap IPO-ed in 2017 which distorted that year’s number, so I would ignore it).

What we see is on a per DAU basis, Snap spent almost half of Meta in the last three years and yet only generated approx. one-fifth of Meta’s ARPU. Without ARPU momentum, Snap’s ability to invest in its own business through the Income Statement will be limited.

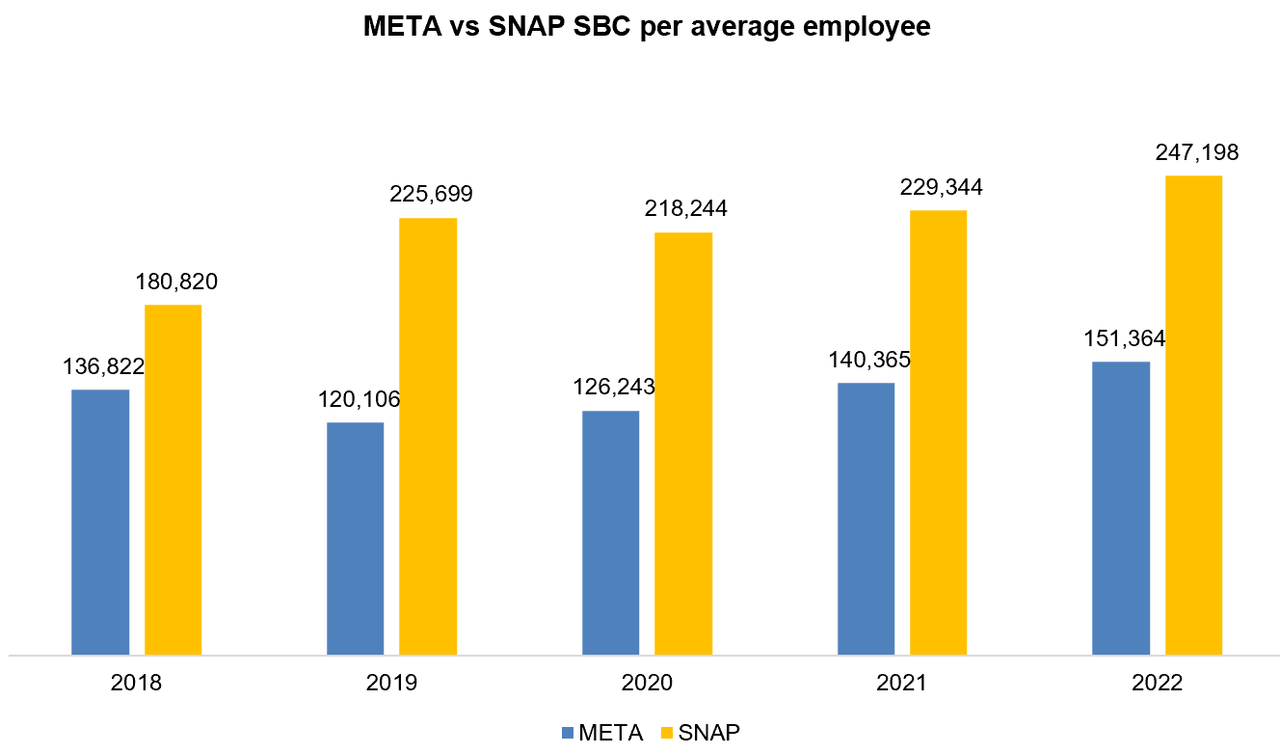

For Meta’s moat, I highlighted two primary moats that are relevant today: a) the ability to attract and price talent, and b) regulatory capture are the primary moats of Meta. As ATT and heightened data privacy concerns wreaked havoc in digital advertising (ex-Google Search), Snap’s ARPU momentum lost its venom which is presenting Meta a great opportunity to widen the gap from their competitors. What perhaps shocked me is Snap’s SBC per average employee vs Meta’s:

MBI Deep Dives, Company Filings, Daloopa

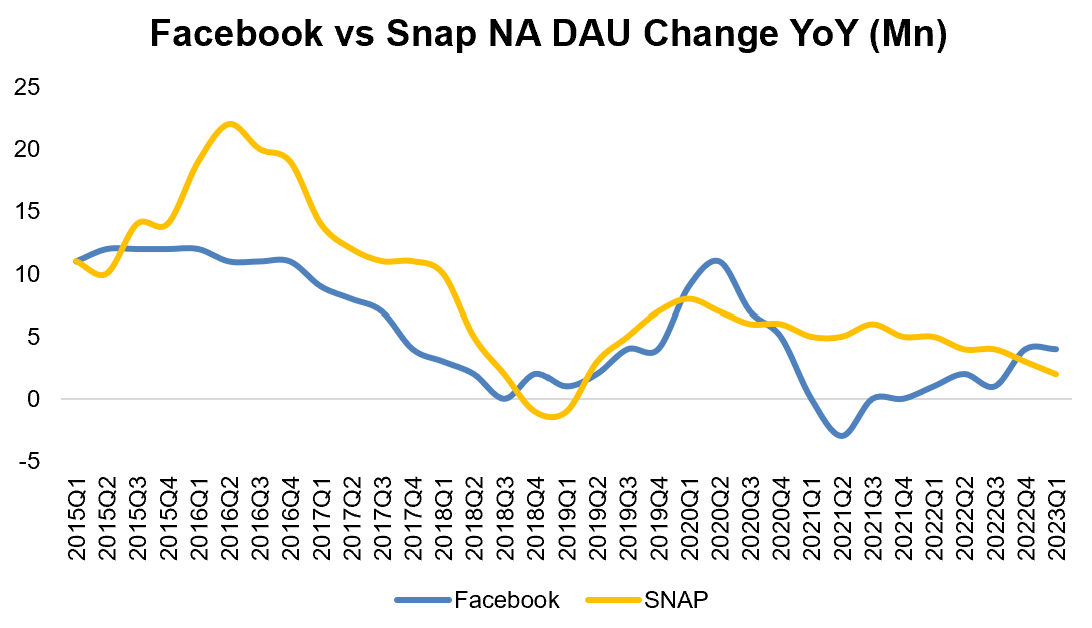

It’s a double whammy for a company such as Snap. They need to invest in the next big thing (AR, AI, paying creators for content, ever-increasing moderation requirement, etc.) while dealing with ATT, GDPR, etc. which directly affect ARPU momentum. The way they could have potentially escaped it is if their users grew fast so that they enjoy some cost leverage, but despite Facebook’s DAU being 2x Snap’s DAU, Facebook surpassed Snap’s incremental DAU growth YoY for the last couple of quarters.

Company Filings, MBI Deep Dives, Daloopa

While some readers took an issue with whether execution moat is actually sustainable over the long run (management can change or even the existing management can lose direction for a variety of reasons etc.), it is perhaps far less controversial to say that Snap (or anyone else) would have to execute out of their skins and hope that Meta loses its way a bit close the competitive gap with Meta. Therefore, you don’t necessarily need to believe whether Meta has an execution moat or not, rather I would invert it: you need to assume Meta would be somewhat incompetent exactly when Snap (or anyone else) would execute extremely well. Of course, it may not have to be binary, but given power laws in consumer internet, it may be harder to generate consistent and durable profit for sub-scaled players.

But this piece is not about Snap vs Meta and despite what the stock prices can make shareholders feel these days, not everything is puppies and kittens for Meta. My steelman bear cases are twofold: a) Meta’s persistent dependency on North America, and b) the evolution from “social media” to “media social” and social interactions online.

Before I elaborate on my bear cases, let me quickly mention the driver of Meta’s revenue today: a) the number of DAU or MAU, and b) the time spent on Meta’s platforms. While much of the bear concerns revolve around users leaving the platform that can be potentially accelerated due to reverse network effects, I think it is the “time spent” function that’s a lot more credible bear case.

Within the time spent function, Meta’s revenue is driven by: a) the volume or number of ad impressions, and b) the effectiveness of ads which affects the price per ad. My first “Achilles heel” for Meta revolves around the effectiveness of ads while the second one is about the volume of ads or the number of ad impressions.

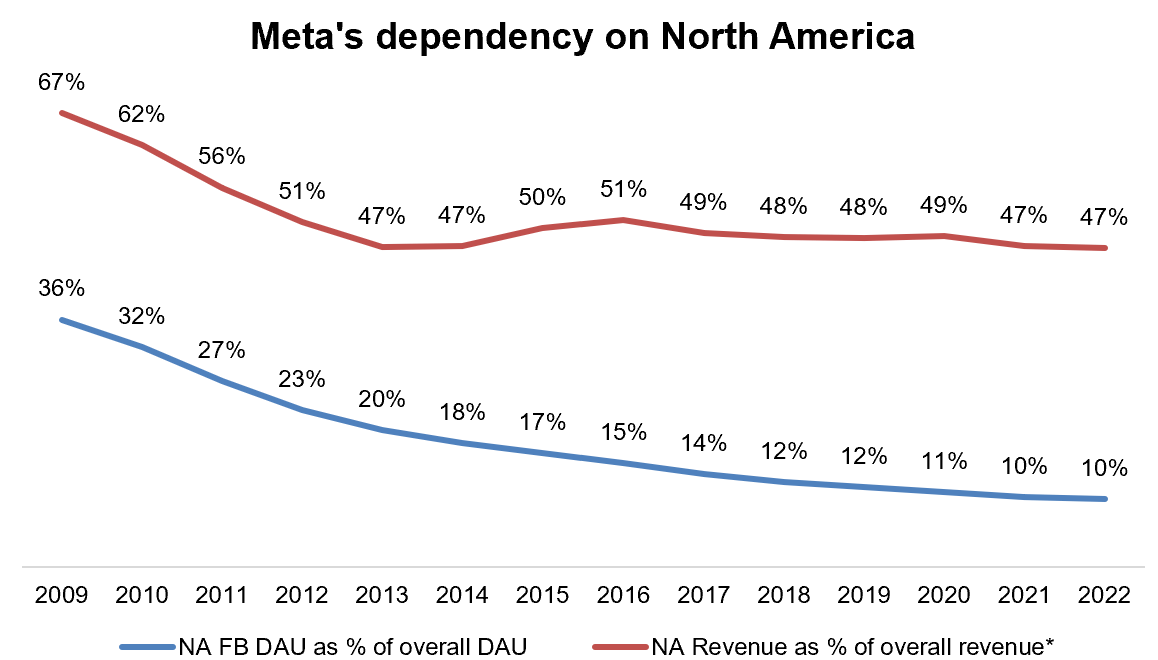

Meta’s persistent dependency on North America

At first glance, it may sound like a strange bear concern, so allow me to explain.

Back in 2009, 36% of Facebook DAU was based in North America (NA) which contributed two-thirds of the company’s overall revenue. 4 years later in 2013, NA users became 20% of the DAU and 47% of the revenue. As Meta grew its tentacles all over the world, NA DAU became only 10% of overall DAU in 2022. Surprisingly, NA’s revenue contribution remains almost half of the company’s revenue.

So, why is this a concern? Two reasons.

First, I suspect while there is a massive difference among regions in terms of ARPU, the cost to serve the users may not have much difference. Meta’s ARPU in NA is ~3x Europe, ~11x Asia Pacific, and ~15x the Rest of the World. How about the costs? Back in 2012 10-K (first 10-K after IPO), Meta had an interesting paragraph that they didn’t repeat anytime in their annual filings since 2012:

User geography also has some impact on our costs, though in general new users in Asia and Rest of World do not require material incremental infrastructure investments because we are able to utilize existing infrastructure such as our data centers in the United States to make our products available to these users. In addition, user growth by geography does not necessarily affect our overall headcount requirements or headcount-related expenses since we are generally able to support users in all geographies from our existing facilities.

I imagine they stopped publishing this paragraph because it may be not true anymore. A 2018 blog post by the company indicated that Facebook’s “safety and security” team employs 30k people (most of them are contract labor and hence not part of the company’s headcount). Such moderation requirement certainly didn’t exist in 2012, and since moderating content requires you to understand local context and nuances, I imagine much of this workforce is region specific. Moreover, if the political will to control citizens’ data within their borders gains critical momentum, data infrastructure costs can also become more region specific. With US-leading ARPU momentum that the other regions are finding hard to keep up with, there likely is a massive margin differential across regions. Any weakness in the North American business may make life challenging for Meta, and there seems to be one company that has a vested interest in making Meta’s life difficult in North America: Apple (Well, their feud is global in nature, but the center of the feud and the potential implications for Meta is most acutely felt in North America since this region is much more mature than others and hence growth primarily depends on effective monetization of MAU.)

Mark Zuckerberg is fighting against Apple to keep his company’s economics:

A guy who rises to the top of a big corporation and owns none of it is much more interested in control than he is in economics. It is just the nature of humanity. A guy who owns his business is already used to control. He never has to fight for control. What he has to fight for is economics”- John Malone

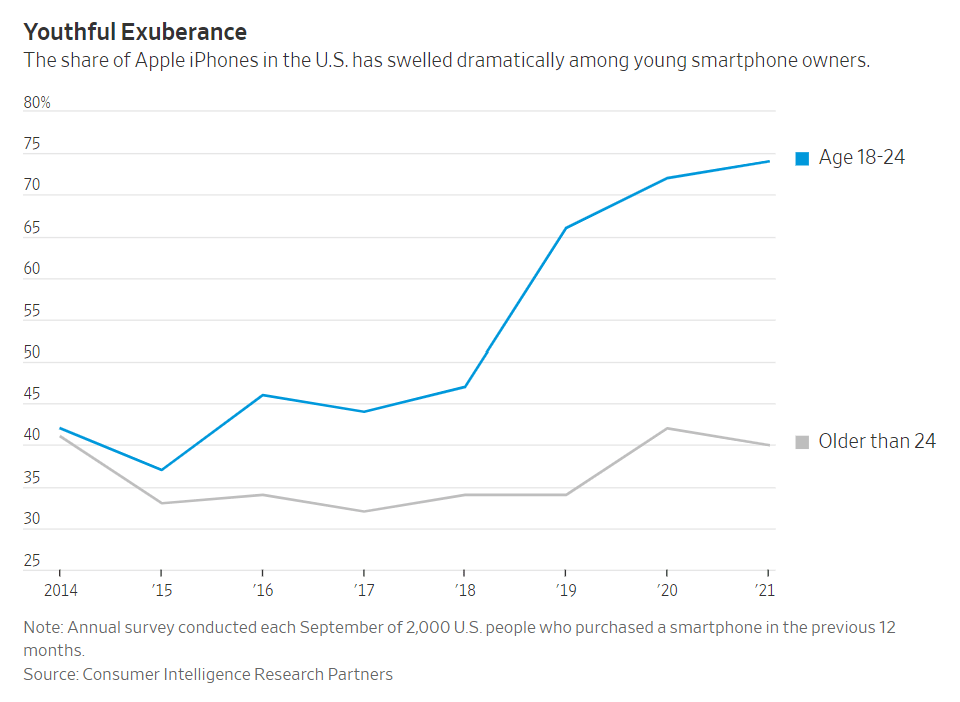

iPhone is dominant in North America and if iPhone’s market share among teens is any indication, Apple’s dominance in the US is expected to only increase over time. Apple’s continued and persistent dominance in the US can be bad news for Meta. From 2017-2022, Meta’s MAU in the NA increased by ~2% CAGR whereas ARPU grew by ~20% CAGR during the same time. It is safe to assume Meta’s MAU growth in NA will not exceed ~2% in the next 5-10 years; therefore, the crux of the question around NA’s growth sustainability hinges upon the ARPU question.

The three largest beneficiaries of current mobile computing are Apple, Google (GOOG) (GOOGL), and Meta (in that order). Apple reportedly receives ~$20 Bn per year from Google which more or less goes directly to Apple’s bottom line. That makes their relationship a bit more symbiotic; despite all the speculation about Apple entering the search market, it would not surprise me if the relationship remains in the current equilibrium for the next 3-5 years (but hard to know beyond that).

But it is Meta’s rise that must be so damn annoying to Tim Cook (and most likely would be to Steve Jobs too if he were alive) since Apple receives peanuts from Meta. Given Apple doesn’t take a cut of advertising from developers, there’s no direct payment flowing from Meta to Apple, but some may argue the rise of social media is what made smartphones much more intriguing to own, and hence, Apple and Meta too have a symbiotic relationship. I am quite confident that Apple feels they catalyzed the smartphone revolution, hosts the wealthiest billion on their platform, and hence deserves some share of Meta’s economics. Evan Spiegel validates such perception:

We really feel like Snapchat wouldn’t exist without the iPhone and without the amazing platform that Apple has created.

A recent post on Meta’s near acquisition of Waze (Google ultimately acquired Waze) made me realize if Apple were run by Mark Zuckerberg, he would probably be angry too that Apple doesn’t receive much in return from Meta even though Meta’s majority of revenue (and likely supermajority of profits) is generated on their phones:

Facebook was the natural fit from the product perspective – they feared dependency on the mobile platforms and wanted to own their location stack, both for their upcoming phone and their apps. We spent a lot of time together mapping out potential integration, but Facebook kept running up against the problem of “What if we help you, you become a huge platform, and then Google comes along and acquires you? We would not be able to compete with them financially.” This was on the heels of the Spotify US launch where Facebook believed they had “built Spotify’s business” but did not extract any value from it.– Noam Bardin (former CEO of Waze)

Guess what, Spotify (SPOT) wasn’t anywhere close to making any money when Zuckerberg felt they had “built Spotify’s business” and lamented that they didn’t get much in return from Spotify. Imagine how Zuckerberg would have felt if a company that runs its products on his platform and generated almost half of Meta’s operating profit but he couldn’t extract much value from that company. Zuckerberg would probably do exactly what Cook had done if Zuckerberg’s role were reversed.

Tim Cook and Mark Zuckerberg are, hence, at odds on the question of economics. Zuckerberg wants to maintain the status quo, and Cook is constantly looking for tweaking the status quo to get his hands on Meta’s economics. Apple suggested Meta pay 30% to Apple for “Facebook boosts”, but Meta declined. Finally, Apple resorted to a privacy narrative and wreaked havoc in the entire digital advertising ecosystem by introducing ATT. While this may sound like past news to readers, the underlying feud is very much alive and may not be totally solved anytime soon.

If ATT turns out to be a boon for Meta and entrenches its moat against sub-scaled players, I cannot imagine Apple thinking the job here is done for them. Given how incentives are stacked, I think Tim Cook would actually prefer Google to keep and grow their share in the digital ad market at the expense of Meta since Apple keeps a healthy economy from Google. Our base case likely should be that this is a protracted cat-and-mouse game between Meta and Apple.

Eric Seufert’s work indicates (also see this tweet) Apple may continue to make life difficult for digital advertisers until they realize it may be easier to come to a deal with Apple than constantly living life on the edge. Zuckerberg probably feels by giving into Apple’s demands, he makes his business fragile over the long run (think decades, not years) and would rather endure the pain but maintain his company’s economics. But make no mistake; if Meta is ever forced to make a deal with Apple because Apple nukes the signal to keep destroying digital ad infrastructure, Meta will get a pretty bad deal from Apple.

It’s not just ad infra that can be influenced by Apple’s whims, Apple has every incentive to help Meta’s competitors. This is why 2022 was so scary for Meta and its shareholders; when Apple was coming after their ability to monetize users’ time spent effectively, TikTok was encroaching and threatening Meta’s ability to keep users engaged on their platforms. While the TikTok threat seems well addressed at this point by Meta (data points about Reels popularity, as well as the political onslaught on TikTok for its ties with CCP, makes this threat a bit tame albeit not fully neutralized), Apple’s shadow still looms large over Meta’s future. The fact that they are also the main competitors in AR/VR makes it even more likely that both companies have incentives to see the other stumble on protecting the cash-gushing machines they both currently have. Meta’s ability to hurt Apple, however, is quite limited today; Apple’s is probably not.

What can Meta do to reduce its dependency on North America? US GDP as % of global GDP (ex-China) is ~30%. Therefore, Meta’s best bet is probably for North America’s revenue contribution to decline to ~30-35% of overall revenue over time. There are two ways Meta can reduce dependency:

a) the bad way: Apple can do it for them by continuously making it challenging to build effective ad infra. and b) the good way: Meta finds other opportunities to monetize its user base by directly integrating the whole sales funnel within their properties. One of the reasons I think international growth hasn’t quite kept pace is Meta’s lack of significant monetization of WhatsApp.

Back in 2014, Meta acquired WhatsApp for $4 Bn cash, 184 mn shares of Facebook (now Meta), and 46 mn RSUs which would imply ~$70 Bn acquisition cost for WhatsApp in today’s price i.e. ~10% of Meta’s Enterprise Value (EV) today. Meta disclosed in the 3Q’22 call that the click-to-messaging revenue run rate was $1.5 Bn on WhatsApp (growing ~80% YoY) which makes WhatsApp’s contribution to be a measly ~1% of Meta’s overall revenue today. While bulls believe all sorts of ways Meta can monetize WhatsApp going forward and imagine Meta can turn WhatsApp into a “super app” in many important countries, especially India and Brazil, Meta has rather been uncharacteristically slow in ratcheting up monetization. That, however, seems to be changing in recent years; WhatsApp business MAU increased from 50 mn in 2020 to 200 mn in 2023. Meta may be on the verge of a massive monetization spigot in WhatsApp which will largely propel its revenue growth outside NA going forward.

Analyzing WhatsApp itself would require a separate piece. My opinion on WhatsApp is largely going to be hinged upon their growth momentum; the problem is Meta may not consistently disclose it which will make it difficult to evaluate monetization progress.

From “Social Media” to “Media Social”

I don’t remember who coined this term on Twitter, but it definitely left an impression on my mind that Meta’s business had gradually evolved from “Social Media” to “Media Social”. In the “Social Media” business, you primarily consume content/media from your social connections whereas, in the current “Media Social” stage, it is the “Media” that’s the center and Meta’s attitude towards the source of the “Media” is increasingly becoming agnostic i.e. all Meta cares about is to entertain you which may or may not come from your social connections.

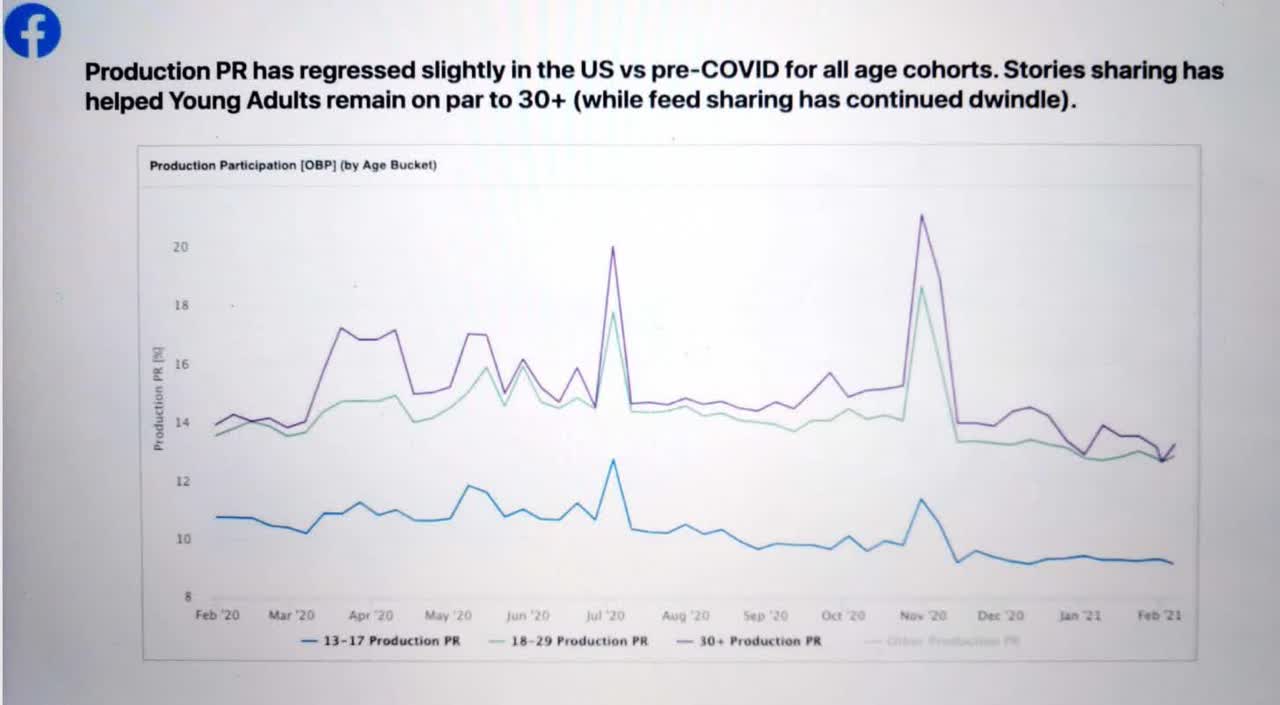

When WSJ published “The Facebook Files” a couple of years ago, this particular slide caught my attention. In many ways, Meta has been “lucky” in facing competition from Snapchat and TikTok. Let me explain.

Meta launched “News Feed” in 2006. Despite vociferous criticism from the users at the time, Feed (as it was later renamed) has been the most scaled profitable “real estate” in the social networking industry.

Meta doesn’t disclose this, but it is highly likely that content posted for Feed per user per month has been on a secular decline. As people become more self-aware of their digital presence, the social broadcast is unlikely to experience a renaissance anytime soon, if ever.

With diminishing content production over time, users would not have a compelling rationale to come back to Meta’s properties. Imagine if there were no “Stories”, Young Adults (18-29 yr olds) would probably produce far less content.

If there were no TikTok, there might not have been any “Reels” (maybe eventually though). Meta would have to clutter your feed in some other ways which could be far less compelling than Reels.

Meta, ironically, needed moderate competition to refresh their social networking apps to help them transition from social broadcast to more social entertainment apps, in which in 5 years people may mostly consume algorithmic content on Feed and discuss/share them on DM.

Meta’s competitors currently face the double whammy of monetizing their users and rising CAC in a post-ATT non-ZIRP world. While Meta is relatively better positioned in those dimensions, there are credible risks in the transition from social broadcast to entertainment.

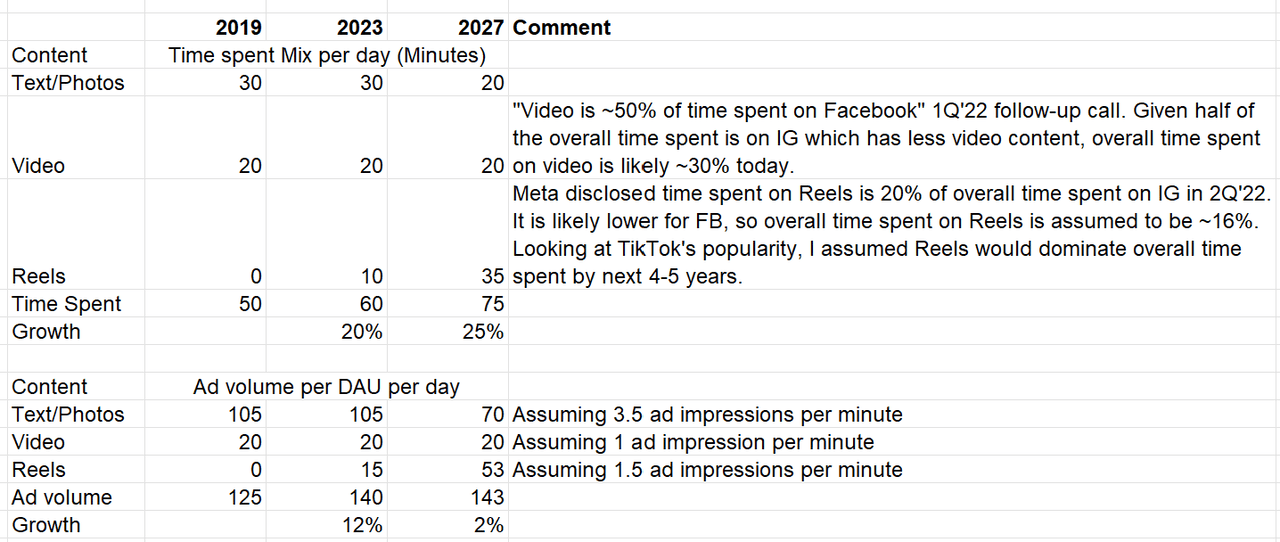

Feed currently has ~25% ad load and given how many ads you can watch while scrolling during a typical ~60-minute session per day, Meta may have to increase time spent materially to keep ad impressions growing. When “Stories” came to the scene and took time away from Feed, it wasn’t as concerning since Stories took very little time to navigate and allows Meta to throw you plenty of ads as you browse through your friends’ Stories. For Reels, this time is different.

Meta indicated the structural challenges related to Reels in the 1Q’23 call:

There are structural supply constraints with the Reels format as people view a Reel for a longer time than a piece of Feed or Stories content, which results in fewer opportunities to serve ads in between posts. That will make it likely more challenging to close the monetization efficiency gap than it was with Stories.…we’re working down the headwind to revenue from the growth of Reels cannibalizing some time that is spent on our more mature ad surfaces, Feed and Stories. And basically, we have been balancing the 2 factors here, which is the degree to which Reels is driving incremental engagement on the platform versus the lower monetization efficiency of Reels relative to the Feed and Stories engagement that it cannibalizes. And ultimately, the overall economics of Reels is really going to be determined by the combination of those 2 things.so while we’re on track to Reels becoming neutral to revenue by end of year or early next year, I do think it’s important to call out that Reels is structurally different from Feed and Stories. And so we don’t have line of sight of getting Reels to monetization parity per time with Feed or Stories anytime soon because of those structural differences.

It is very much possible such structural changes may mean the best days of profitability of “Feed” is behind us. To substantiate this point, let’s imagine a DAU spent ~50 minutes on Meta’s Family of Apps (FOA) properties in 2019. The following table outlines why even with the assumption of increased time spent over time, the structural challenges may be a strong headwind for ad impression growth for Meta. Without growing ad loads, impressions, and limited room for DAU/MAU growth, revenue growth will be largely dependent on price per ad which relies on targeting and the quality of ad attribution. If you remember the bear case discussed above, Apple may make things difficult for Meta in its journey to enhance ad targeting and attribution infrastructure.

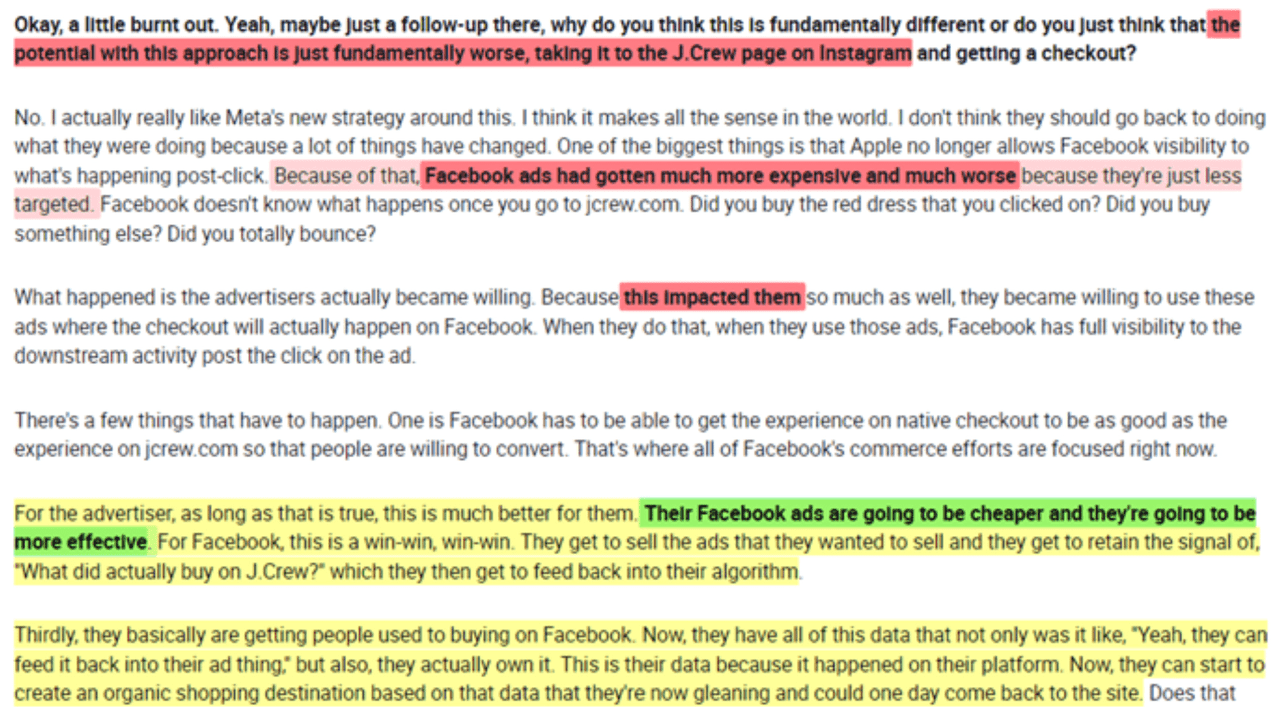

Meta doesn’t seem to be oblivious to such glaring risks; monetizing messaging and perhaps shopping will need to pull the lever for Meta this decade both of which have been in the investor conversation for the last 4-5 years but never quite materialized to the extent investors hoped. Rihard Jarc shared an insightful expert network interview that outlined why Meta’s shopping efforts failed so far and why that might still change. While I encourage you to read the full thread, the following bit stood out to me:

As a shareholder, when I look forward, I do think Meta will have to make shopping and messaging work in a meaningful way for it to be somewhat immune from “Apple” risk (i.e. they may not be fully immune from Apple risk; just that they will be hurt less). Once you assess the level of pain Apple can inflict upon Meta, it probably starts making a bit more sense why Meta is so incredibly eager to control the next computing platform.

Of the big tech companies, Meta is one of the easier companies to hypothesize bear cases today. 10 years ago, it was actually Apple that was easier to hypothesize bear cases e.g. it’s a hardware company and hardware companies don’t make the kind of margins Apple does; Apple will lose market share to Samsung (OTCPK:SSNLF), Google, Microsoft, etc. I try to be a diligent student of big tech companies and the more I studied history, the more it reminded me to be mindful of how hard it is to predict the evolution of moats.

As you can probably tell, I have a decent amount of sympathy for bear cases about Meta. But Meta’s management’s overall historical track record as well as some potential wild cards still keeps me a shareholder today.

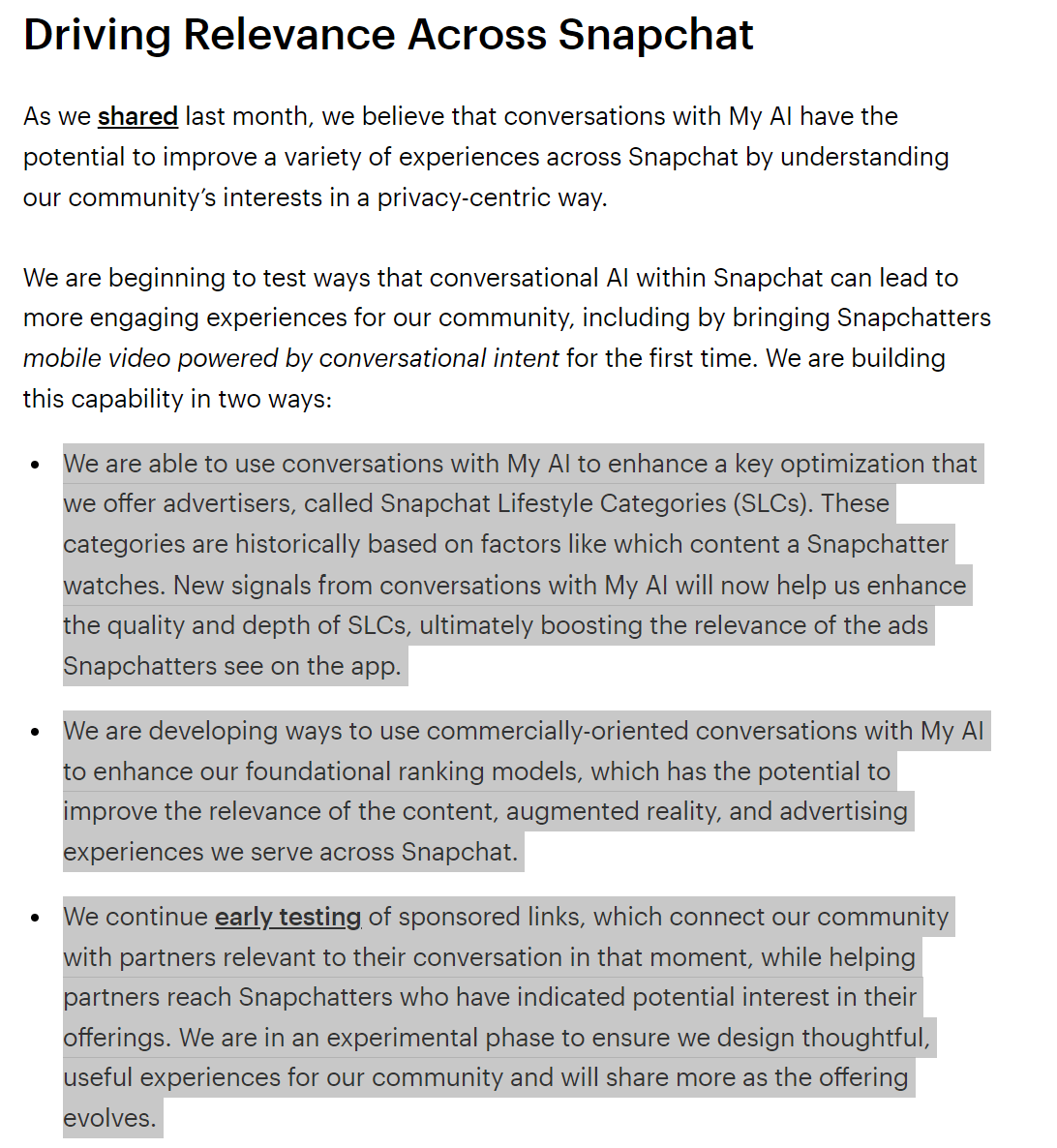

Reality Labs which is still likely assigned a steep negative value today by investors is one such wild card, but the other wild card that I am starting to ponder a bit more on is AI chatbots. Snap recently shared their early insights on their chatbot called “My AI”. The whole report is very, very interesting and can have potentially uncomfortable implications for Google Search (disclosure: long). Meta has three separate messaging properties (Messenger, WhatsApp, and IG DM) consisting of ~4 Bn MAUs; all three will likely be swarmed with AI chatbots by the end of this year. While we are way too early here (Meta hasn’t even launched anything), the landscape can shift quickly in digital advertising. If chatbots can truly take off on messaging properties, Meta, which generates less than half of Google Service’s revenues, may end up gaining material market share from Google.

Snap

Even if the bear cases for Meta play out, it is unlikely to be a terminally ill business and hence, the question of valuation is quite relevant. Meta currently trades at ~17x NTM EV/EBIT, but if you assign RL a valuation of zero (debatable; can be negative), it trades at ~12-13x NTM EV/EBIT, a significant discount from both S&P 500 Index (~18x) and Nasdaq 100 (~23x) most of whose constituents add back SBC (so the actual discount is likely even higher).

As I have mentioned before, I always consider valuation in terms of questions. The response to those questions is not binary but a probability-weighted answer. Most people consider probability to be an inherently quantitative concept with objective and precise answers, but for fundamental active investors (especially with concentrated portfolios) dealing with probability is primarily qualitative in nature. Because it is the probability, I do and will routinely assess and update it as fundamentals and valuations change.

Thank you for reading.

For more detailed valuation work on Meta, read this post.

Disclosure: I own shares and January 2025 $50 Call Options of Meta

Editor’s Note: The summary bullets for this article were chosen by Seeking Alpha editors.