Summary:

- Boeing’s corporate culture shift post-McDonnell Douglas merger has led to quality declines, financial struggles, and a tarnished reputation.

- Meanwhile, Airbus has successfully deployed autonomous flight technology and maintains solid financials despite lingering pandemic supply chain issues.

- Boeing’s future hinges on CEO Ortberg’s ability to restore engineering excellence and financial stability; investors should wait for sustained signs of recovery before buying in.

- Airbus is well-positioned to dominate the autonomous aircraft market and possibly become the preferred supplier, making it a strong long-term investment notwithstanding a premium stock valuation.

Michal Krakowiak

Introduction

In late 2023, I wrote an article about the opportunities in front of Boeing (NYSE:BA) and Airbus (OTCPK:EADSF) (OTCPK:EADSY) based on the companies’ development of autonomous flight, and I rated both a “buy” because of the rewards that the companies could reap from autonomy. While Airbus’s autonomy progress is on track, Boeing’s whole business has suffered setback after setback.

In this article, I will revise my long-term thesis on Boeing, and account for an aspect of the company that I should have considered from the beginning: Boeing’s corporate culture. I will also update and reaffirm my thesis on Airbus.

Boeing – Tracking the Flight Path of a Fallen Angel

The Old Boeing

In the beginning, Boeing was a company focused on building high-quality planes. For decades, this is what it did, and it did this well. Boeing was a large company for many years, but it did not behave like an ordinary company.

Before the 1990s, the culture at Boeing was very engineering-centric. The people in charge of the company obviously cared a good deal about ensuring the business was sustainable, but they cared more about the quality of the products Boeing put out. Boeing had a reputation for quality engineering, a reputation that generated a memorable slogan about the company and its aircraft: “If it ain’t Boeing, I ain’t going!”

From the company’s participation in WWII producing bombers for the US military (e.g. the B-17, B-19, and B-52), to the company’s creation of the arguably revolutionary 707 aircraft, Boeing was trusted to make planes far and wide, before expanding into spacecraft and beyond. Even during Boeing’s difficult period in the 1970s, quality was paramount at the company.

The New Boeing

In 1992, Philip Condit became chairman of Boeing, and then CEO in 1996. Under Condit, Boeing moved its headquarters away from Seattle, its engineering hub. Many say this was the beginning of the problems at Boeing, arguing that the move separated Boeing’s management from its engineers and imperiled the company’s engineering-centric corporate culture. But the Seattle move was in 2001; Boeing’s culture had been under threat for years by then.

Back in 1997, Boeing purchased the recently struggling plane maker and defense contractor McDonnell Douglas. To really understand how things got bad at Boeing, one should understand how things got bad at McDonnell.

The Boeing-McDonnell Merger – “Bought them with their own money”

McDonnell Douglas had been a well-known and respectable aerospace firm until it started running into trouble in the 1980s. In 1989, CEO John McDonnell instituted the Total Quality Management System, or TQMS, that fundamentally reshaped how engineers were allowed to work on aircraft at the company. It resulted in disruption to 5000 managerial jobs and the net loss of around 2200 management positions, and dealt a big blow to company morale. Demoralized employees supposedly came up with their own meaning for the TQMS: “Time to Quit and Move to Seattle”, the home of Boeing at the time. A layoff of 20,000 workers to cut costs and increase profitability came soon after, further degrading morale.

This is likely where problems started within McDonnell Douglas, as the implementation of the TQMS signaled that a profit-focused, management-dominated culture was being injected into the company. True, the company had been struggling with profitability since the merger of McDonnell Aircraft and Douglas Aircraft, but its decision to address profitability by utilizing top-down managerial strategies to boost efficiency and trim costs, instead of relying on bottom-up engineering expertise, was not the best long-term solution.

In any case, the focus on profit and efficiency combined with removing engineers’ agency coincided with a difficult market environment and continued operational struggles for the company during the 1990s – struggles that opened the door for a merger/buyout of the company by Boeing. However, Boeing was setting itself up to inherit the problems inherent in McDonnell Douglas’s corporate culture, largely due to McDonnell Douglas’s executives taking a great degree of control of Boeing after the merger.

After Boeing CEO Condit’s departure, former McDonnell Douglas CEO Harry Stonecipher took the reins at Boeing in 2003. Stonecipher was reportedly influenced by Jack Welch, who famously (or infamously) sought profit, efficiency, and workforce reduction wherever it could be found. Under Welch’s leadership, General Electric (GE) experienced a boom in market cap, but then suffered a fall in financial and product outcomes as well as its reputation in the years after Welch’s retirement.

Stonecipher and the Boeing/McDonnell executives who followed the Welch-esque profit-focused corporate style took Boeing down a similar path. Without the influence of Boeing’s engineers in Seattle, Boeing’s management was undeterred in focusing on cost cuts and efficiency; as a result, production workers and managers cut corners while designing, developing, and building Boeing’s product lines. That strategy may have paid off in the short-to-medium term, but it’s easy to see why it rarely ends well long-term.

Such a radical departure in Boeing’s approach to management and engineering prompted many observers to grimly note that Boeing’s ethos was apparently replaced with McDonnell Douglas’s during the merger, especially with McDonnell management largely taking over the new firm. Hence, many say that McDonnell became the true surviving company, and that “McDonnell Douglas was so cheap, they bought Boeing with Boeing’s own money.”

Logically, then, after nearly three decades, the Boeing-McDonnell merger is now being blamed for many of Boeing’s managerial and financial problems in recent years. The merger’s effects have been used to explain the Boeing 737 Max crisis, Boeing’s failures with its Starliner spacecraft, and the change in corporate culture that led to Boeing’s overall decline in product quality.

Today’s Boeing – Financials and Valuation

Boeing today is suffering in both its reputation and financials, largely thanks to its McDonnell Douglas-influenced culture. Surprisingly, the full weight of the consequences of this new culture is only now bearing down on the company.

Just a year ago (per the Q3’23 earnings call), Boeing was expecting $10 billion in free cash flow between 2025 and 2026. But in the Q3’24 earnings call a week ago, the CFO confirmed that the company expects Boeing’s free cash flow to be negative in 2025, and that 2025’s negative FCF will be “significantly better” than 2024’s FCF (which is a pretty grim preview of Boeing’s full 2024 profitability numbers).

Based on management’s statements, it’s safe to say that last year’s guidance of $10 billion in FCF for 2025-26 is probably out of reach now. Considering the issues the company is facing, it’s understandable why:

- A labor strike has slowed Boeing’s operations to a crawl, and cost the company and workers $5 billion in its first month. That strike is still ongoing, since Boeing’s latest offer to the union was rejected by the striking workers; costs from the strike will increase as it proceeds onward.

- Meanwhile, per reporting from eagle-eyed SA analyst Dhierin Bechai, Boeing’s orders and deliveries are down from last year, meaning Boeing’s revenue sources are drying up after years of negative publicity over its products; the strike will likely slow production and deliveries further, thereby cutting Boeing’s revenue generation.

- Boeing is also considering asset sales to keep finances solid. This would shrink its business’s output and could eliminate whole business lines, along with big sources of future revenue and profit.

- Per Reuters, 17,000 job cuts are looming at Boeing (which will hurt company morale), and the company is planning to issue both stock shares (which may hurt shareholder value) and new debt (which may hurt company finances down the line).

On top of all of this, Boeing is not profitable, and has not been since 2018, the year of its last positive net income. The company has been running on debt ever since, and cash reserves total a bit north of $10 billion at time of writing; trailing 12 month [TTM] net losses were nearly $8 billion, indicating just over a year of runway left at the current burn rate. But even if Boeing was operating at breakeven, the company has over $11 billion in debt coming due by 2026, which is more than its cash balance. With all these problems, it’s no wonder that Boeing’s credit rating is just shy of junk bond territory, making BA nearly a fallen angel stock.

All is not lost, though. On October 28th, Boeing announced that it will raise about $20 billion in capital via strategic share issuance. $20 billion in new capital will not wipe out Boeing’s problems, but it will provide the company some valuable cushion to address its financial woes, and in the best case, this raise, if successful, may reduce the need for the other bulleted remedies above, most of which could be quite painful for Boeing and its stakeholders. Still, this does not change the fact that Boeing’s financial situation is currently quite dire, and far from resolved long-term.

In short, Boeing’s finances are essentially in shambles, and the company is scrambling to fix them.

As far as BA’s valuation goes, many metrics aren’t applicable to Boeing, since it generates no profit and its finances are in a state of flux. BA’s Price to Sales ratio is ~1.35, discounted a bit to the industrials sector’s ratio of ~1.5. But valuing shares of a company in financial trouble is difficult, and ultimately, BA’s value will only become clear after Boeing addresses its financial issues and its corporate culture.

Is My AI-Based Thesis for Boeing Broken?

My 2023 article on Boeing and Airbus, titled Boeing, Airbus, And The Autonomous Aircraft Opportunity, focused on the benefits that autonomous flight would bring to the two plane makers if they could capitalize on it. A critical part of my thesis focused on benefits of autonomy that are not directly financial in nature:

Beyond the balance sheet, however, I believe that autonomous flight will become a prerequisite to operate in the defense and commercial aircraft industries by the next decade due to its capacity to substantially reduce error rates compared to humans. Consequently, the companies operating non-autonomous craft will have to either settle for a greatly reduced market share, try to compete with these two behemoths, or license Boeing and Airbus’s autonomous software from them. So, even if the bottom lines of Boeing and Airbus only see a moderate impact, I think their positions in their industries will be secure due to their full embrace of autonomy. Such security, in my view, is priceless.

What I failed to account for in that analysis is that Boeing’s corporate culture could delay or derail its progress toward developing its autonomous flight software, along with degrading its reputation and harming Boeing’s product quality and product sales. Autonomous flight may be critical in securing Boeing’s place in aerospace, but high product quality, a good reputation, and solid finances are also critical, and Boeing is now lacking in all three.

Assuming that Boeing’s autonomy is still on track and hasn’t been negatively affected by its leadership decisions, the company’s current trajectory implies that even autonomy won’t be enough to save the plane maker. Sure it still has a backlog now, but for how long? Will Boeing’s new CEO Kelly Ortberg be able to quickly and effectively shift this giant company’s entire corporate culture before other plane makers try to take its place in the airplane oligopoly?

On the matter of competitors, Airbus is arguably pulling ahead of Boeing in plane deliveries, and is already ahead of Boeing in autonomous flight development (which I will address later in this article). How long before it takes an insurmountable lead against Boeing? How will it take for a competitor like Embraer (ERJ) to invest in the infrastructure and machinery needed to make the planes Boeing does, and at the same volume and quality Boeing used to? And beyond that, how long until Embraer independently unlocks fully autonomous flight? The company has already put together autonomous takeoff software, in addition to pre-existing autonomous landing software. Those two capabilities encompass 1 of the 3 necessary elements of flying completely autonomously (which I will review in the Airbus section), and Embraer is not standing still after recent autonomy achievements either. The company has produced a concept for a fully autonomous passenger plane, and while it may be several years before any such plane is produced by the company, Boeing will be distracted putting out fires while Embraer focuses on making its autonomy dreams a reality. Is it possible that not just Airbus, but also Embraer, both realize their autonomy plans before Boeing does?

There are too many unknowns when it comes to both Boeing and its competition, and I’m not sure that the prospect of fully autonomous flight in Boeing craft can make up for them. The Boeing AI/autonomy thesis isn’t necessarily broken, but the long-term Boeing “buy” thesis is.

Boeing Risk

The only notable risk to my new Boeing thesis is that CEO Kelly Ortberg will aggressively change Boeing’s corporate culture back to one centered on engineering excellence, while shoring up the company’s finances, boosting its product quality and encouraging the continued development of autonomous flight software for wide deployment in Boeing aircraft, all while preserving as many business lines as possible. If Ortberg is able to do all this, then the current low point for the company and its stock will have been an opportunity to buy the dip and hold for the long term.

Unfortunately, it all seems to be riding on Ortberg, and until we have more clarity on what he does and how successful he is, all we can do is wait and see for now.

Airbus – Enduring and Executing

Airbus Autonomy Progress

Per an early-October report, Airbus’s A350-1000 aircraft has demonstrated the ability to reliably automate some of the hardest parts of flying – taxiing, takeoffs, and landings. This feat has been several years in the making, since the A350’s software has been doing test flights since at least 2020.

As of September 2024, Airbus’s official orders and deliveries page (opens in excel) shows orders of the A350-1000 totaling over 300 planes, and deliveries of 88 planes so far this year. In other words, Airbus is actively commercializing a big piece of autonomous flight today, and is reaping the ever-growing rewards of it with every passing month, and with each new incident-free delivery, and with each incident-free flight performed mostly autonomously.

To be fair, the A350-1000 does have a few problems with faulty engine components, but that’s a hardware issue – Airbus’s A350 software has generated no complaints or concerns among Airbus’s customers that I am aware of. The Airbus autonomy thesis therefore remains intact, as Airbus is executing on its “autonomous” software deployment seemingly without incident.

But even with the impressive feats of the A350-1000’s flights, Airbus’s autonomy isn’t complete just yet. As I noted in my previous piece last year:

According to this article on what differentiates self-flying aircraft from autonomous aircraft, self-flying aircraft are essentially just aircraft with autopilot that allow them to cruise, while autonomous aircraft are able to independently do at least three critical things in addition to simply cruising: take-off and land; seek out obstacles; and alter course to manage unpredictable situations.

Among [Airbus’s autonomous software offerings] is Dragonfly, which likely alters course to manage unpredictable situations like pilot incapacitation[;] Deckfinder, touted as “The all-purpose landing aid”[;] and ATTOL (Autonomous Taxi, Take-off and Landing), a project that has allowed the company to take-off and land commercial aircraft using vision and image recognition, presumably avoiding obstacles in the course of taking off and landing.

It is only the third Airbus autonomy offering, ATTOL, that allows the company’s A350-1000 planes to perform their current “autonomous” feats. Once the other Airbus software’s capabilities are folded into Airbus’s ATTOL-enabled craft, the company will unequivocally achieve full autonomy. To that end, the deployment of ATTOL-enabled aircraft with no software-related complaints is a major stepping stone, and indicates that Airbus is well on its way to establishing full autonomy in its products.

Airbus Financials and Valuation

Both Boeing and Airbus are still recovering from supply chain issues caused by the pandemic shutdowns in 2020, with Airbus apparently struggling to gather enough engines to finish building its planes this year. Despite this, Airbus’s supply chain issues are a breeze next to the multiple crises happening at Boeing.

With help from its semi-autonomous aircraft deliveries, Airbus’s financials are displaying appealing resilience. Airbus’s Q3’24 earnings report has just been released, so I crunched the company’s TTM numbers by adding the consolidated 9-month numbers in the Q3’24 report to the quarterly numbers from Q4’23.

Airbus’s revenue has risen to ~$74 billion TTM, up a bit from $72.2 billion for the fiscal/full year 2023 [FY23], a small but noteworthy increase year-over-year. TTM net income is ~$3.5 billion, down from $4.1 billion for FY23, a slight decline in profitability. In absolute terms, Airbus saw a ~$2 billion revenue bump, but with a $600 million net income decline in the past year.

Compare those numbers to Boeing’s: from FY23 to TTM, Boeing’s revenue fell from $77.7 billion to $73.2 billion, and net income fell from losses of -$2.2 billion to -$7.9 billion. Boeing lost $4.5 billion in revenue and added $5.7 billion in net losses in the past year; all things considered, Airbus’s operations are running quite smoothly and quite profitably.

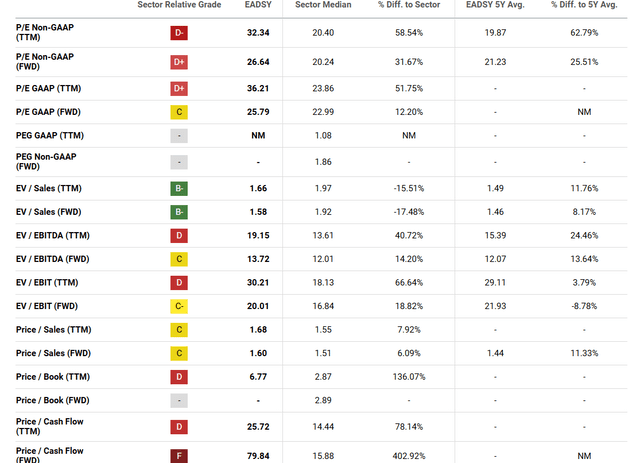

As for Airbus shares’ valuation, Seeking Alpha provides the following data:

P/E for EADSF/EADSY shares is at a 10-60% premium, depending on accounting method and earnings horizon; P/S is at a premium of less than 10%; P/B is more than double the sector ratio; and P/Cash flow is 78-400% of the sector, depending on earnings horizon.

Most valuation metrics show that EADSF/EADSY is trading at a premium, either a large one or a small one depending on one’s preferred metric. As far as I’m concerned, the premium is justified – Airbus is one of a handful of aircraft companies, and likely the first major plane maker, to sell large commercial aircraft with significant autonomous capabilities. As I said in my previous article, fully autonomous flight will likely be mandated in the future to curb human error, so the company is going a long way toward future-proofing its business by deploying incident-free semi-autonomous craft now.

With Boeing’s issues on full display, it’s possible that only Airbus will be trusted by aerospace customers to deliver autonomous aircraft in the next few years. Those customers who purchase Airbus’s A350-1000 and other autonomous Airbus craft may develop an affinity for the company’s products for many years afterward. In time, these customers’ positive experiences with Airbus products may even prompt them to designate Airbus their go-to autonomous craft supplier, solidifying Airbus’s position in the market. Buying EADSF/EADSY stock ahead of this virtuous cycle would benefit long-term aerospace investors, especially since the cycle will intensify when Airbus announces that it makes products that are fully autonomous and pilotless.

Airbus Risks

Risks to Airbus include continued supply chain issues and raised interest rates. Supply chain issues will cap the rate at which Airbus can produce planes; meanwhile, high interest rates may cap consumer demand for flights as well as increase expenses for airlines, which would cap airline revenues and demand for planes, which would hinder Airbus’s plane sales.

Another risk to Airbus is that it undergoes a negative change in its corporate culture, like Boeing did. While this risk doesn’t appear to be on the horizon, Boeing proves it is a risk that cannot be ignored. If the last 30 years at Boeing has taught us anything, it’s that bad corporate governance can lead to bad products and bad financials.

Yet another risk is that Airbus’s products disappoint customers or otherwise underperform. This would eliminate the possible virtuous cycle that would get customers to be more loyal to Airbus and settle in to buying its products exclusively.

The last risk is that Airbus is unable to, or struggles to, complete its autonomous software, e.g. by making it capable of independent obstacle avoidance and planning for unpredictable scenarios. Failure or delay in this effort would allow others, including Boeing and Embraer, to catch up in producing full autonomy software and fully autonomous aircraft before Airbus, reducing its competitive advantage in the long term.

Takeaway

A year ago, I rated shares of both BA and EADSF/EADSY as long-term “buys” due to the fully autonomous flight software the two companies were preparing to develop and deploy in their aircraft. Airbus’s bullish story remains unchanged, but until we see some fundamental changes in how Boeing’s management operates, as well as a change in the company’s financial situation, a medium-term “hold” is more appropriate for the American plane maker.

Boeing’s long-term future in the age of autonomous flight is still taking shape, and since past mistakes by the company have both damaged and clouded its future, I cannot rate Boeing on a long-term basis at this time. On balance, I think selling BA shares would be premature, as the company could bounce back over the next few years. However, I think investors would be best served by keeping spare capital on the sidelines, at least until Boeing shows signs of a sustained recovery and improved corporate governance.

By contrast, Airbus’s future in autonomous flight looks bright, and its stock is likely to benefit greatly as the aerospace industry and the stock market digest that new reality. I see little reason for investors to wait to buy shares in the European plane maker, even considering their valuation premium.

I therefore revise my rating on BA shares to a hold, and maintain my rating for EADSF/EADSY at a buy.

Editor’s Note: This article discusses one or more securities that do not trade on a major U.S. exchange. Please be aware of the risks associated with these stocks.

Analyst’s Disclosure: I/we have no stock, option or similar derivative position in any of the companies mentioned, and no plans to initiate any such positions within the next 72 hours. I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it (other than from Seeking Alpha). I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.

Seeking Alpha’s Disclosure: Past performance is no guarantee of future results. No recommendation or advice is being given as to whether any investment is suitable for a particular investor. Any views or opinions expressed above may not reflect those of Seeking Alpha as a whole. Seeking Alpha is not a licensed securities dealer, broker or US investment adviser or investment bank. Our analysts are third party authors that include both professional investors and individual investors who may not be licensed or certified by any institute or regulatory body.