Summary:

- This article transparently walks through my moderately bullish assessment of Amazon while attempting to give investors the tools to properly evaluate Amazon for themselves.

- Amazon’s opaque financial reporting causes valuations of the business to vary considerably because analysts/investors are forced to guess even more than usual.

- Disclosure of margins, the most important part of the Amazon story going forward, is particularly poor.

- The current price of ~$85/share is (very roughly) a conservative fair value, assuming Amazon simply reverts to profitability, but unforeseen cost reductions could enhance returns.

- Beware the “Sum of the Parts” Bulls and the “P/E Ratio Bears”.

4kodiak/iStock Unreleased via Getty Images

Introduction

The market can’t make up its mind whether the issues at Amazon (NASDAQ:AMZN) are temporary or prolonged and, as a result, the stock is down 50% from its highs. As investors, we need to determine whether these circumstances have created a rare opportunity where we can buy a small piece of a quality business on sale. I believe this is the case, but I’d like to try to give readers the tools to determine their opinion for themselves. Let’s begin.

Amazon – The Business

As most readers will know, Amazon operates multiple, highly distinct businesses operating in conjunction with one another. Its online retail operation, Amazon.com, generates most of the sales but operates at a loss. However, it is the machine that digs the moat around Amazon’s business castle and drives profitability in other segments. Amazon.com is so dominant in e-commerce that independent “third-party” sellers that lack brand awareness (for example, any company less well-known than NIKE (NKE) or Lululemon (LULU)) consistently list their products on the site, a service for which Amazon takes a considerable referral fee. In addition, Amazon offers third-party sellers, and recently sellers on other platforms like Shopify (SHOP), an optional service known as “Fulfilled by Amazon,” or FBA for short, in which Amazon takes care of storage, packaging, delivery (by Prime), even customs, on behalf of the seller, considerably simplifying and streamlining the process of owning an online business – for a fee, of course.

Another result of Amazon.com’s dominance is the attractiveness of the site as a platform for advertising. This is especially the case because, unlike Google Search (GOOG) or Facebook (META), people go to Amazon specifically with purchasing something in mind; the value proposition with advertising on Amazon.com is high. Moreover, built into Amazon is a Costco membership-style business with Prime. With same-day delivery and a host of other features, like a streaming service that features a terrible Lord of the Rings spin-off and the NFL’s Thursday Night Football in America (the balance of which strikes me as about the same value as a $1.50 hot dog), Prime is growing subscribers quickly and operates as the gate to their business castle, keeping competition out, and customers in. A smaller part of Amazon’s business is physical stores like Whole Foods, and a segment blandly branded as “Other,” which nonetheless spawned important aspects of Amazon’s business today like third-party selling services (3PSS), advertising services, and most importantly, Amazon Web Services.

Beginning as simply selling server space Amazon.com wasn’t using, AWS has grown into the cloud computing platform behind much of the internet; if AWS were to go down, so would half the internet. Incidentally, so would most of Amazon. This is because AWS’s profits effectively subsidize the rest of the business. Is this fair to competitors? Perhaps not, but AWS is why Amazon can invest into same-day delivery for Prime, afford to make a loss on Amazon.com, develop third-party seller services and continue research and development in its mysterious “Other” segment. The internal founder of AWS, Andy Jassy, recently replaced Jeff Bezos as the CEO of Amazon.

Recently, Amazon spent a lot of money expanding its fulfillment network to meet pandemic demand, which promptly dropped off. In addition, inflation drove up costs, the federal reserve rose interest rates, and economists are predicting a recession in 2023, all of which have contributed to the 50% drop in Amazon’s share price. However, the moat continues to be wide and deep, with over 60% of online product searches beginning on Amazon.com, and Prime members doubled from 2018-2021. AWS continues to grow profitably, funding the rest of the business, and growth opportunities, namely third-party seller services and advertising, are still relatively in their infancy. Moreover, we don’t know exactly what’s cooking in “Other,” but the next growth tentacle could come at any time. It’s my expectation that Amazon can overcome temporary setbacks and revert to its mean: consistent growth.

Those who disagree point to government regulation bringing down its dominance in e-commerce and a slowdown in AWS’s growth threatening its profitability. While it’s true that AWS’s growth has slowed, “slow” in this case means 27% annually at 30% margins; unless something drastic happens, this slowdown doesn’t concern me in the slightest. In addition, advertising and 3PS are starting to pick up some of the profitability slack from AWS, so we have a backup plan. As for government regulation, while it’s true that Big Tech has been coming under the microscope, the US government couldn’t even decide on a speaker of the House of Representatives, let alone take on Big Tech’s legions of lawyers. Regulation is not imminent.

Additionally, Big Tech provides a lot of jobs. If regulation starts to threaten people’s jobs, we can be sure representatives would hear about it and take their foot off the gas. Lastly, unlike some monopolies, Amazon provides honest-to-goodness value and convenience to customers, as opposed to extracting profits from them. In other words, Amazon is not OPEC. It’s my opinion that the long-term bearish case on Amazon is tilting at windmills.

Plenty disagree, of course, helped by the fact that Amazon rarely has anything to say about the workings of its business to the public. Common sense would dictate that a business as massive, complex, and interdependent as Amazon would do their utmost to elucidate its owners (shareholders) as to the operations of the business. Alas, this is not the case.

The Problem – Amazon’s Reporting

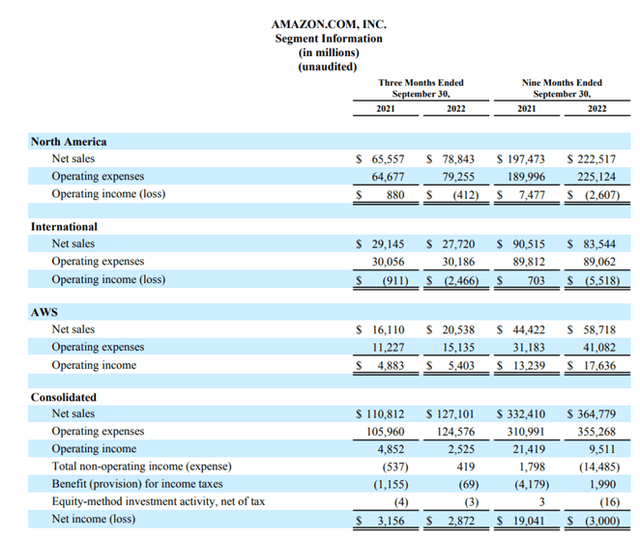

In addition to the customary balance sheet, cash flow statement, and income statement, here’s what we get from Amazon:

For all Amazon’s complexity, we get two generic geographical segments, “North America” and “International,” and an oddly non-geographic segment, AWS, despite the fact it presumably does business in North America and internationally (where else, Mars?). The consolidated numbers are less than impressive; to an undiscerning eye, they are downright awful. How can Amazon lose $3B and have a P/E of 76? A fair question, and one that is not answered in their financial statements, but I will address later. For those justifiably wondering, “What about advertising, third-party seller services, and those other business lines you mentioned?” Well, here’s what we get for those:

Business Segments (Amazon’s Q3 Earnings)

Revenue numbers and percent changes are what we get. Unlike AWS, where we can see how much money it’s making, we are simply not told the margins of its other segments, except in aggregate (and therefore useless) categories, like “International.” For valuing the company at this exact moment, these categories are fine, but investors and shareholders (the owners) want to be able to get a sense of the future. Different segments grow at different rates and have different profit margins. In five years, the revenue and profit mix of Amazon could be substantially different than it is now. For example, advertising is a famously high-margin business; it would be helpful to know how much money it makes (or does not make) so we could estimate with some accuracy what it could be earning for Amazon five years out. Something similar is the case for 3PSS. Instead, we must rely on potentially uninformed outsider information, which contributes greatly to the pervasive ambiguity regarding Amazon’s value and long-term growth.

In addition, some segments need completely different metrics than even sales and profit to get a full picture of their value. A retail business like Nike or Walmart, for example, usually discloses Gross Merchandise Volume, the dollar value of total sales in the company’s stores. Gross Merchandise Volume is often the long-term driver of success for retail operations. Amazon.com doesn’t disclose their GMV, while NIKE (NKE) or Walmart (WMT) are required by investors and shareholders to do so; if they chose to leave it out, they would quickly receive backlash. In addition, businesses whose customers have accounts or subscriptions, like Facebook, Netflix (NFLX), or Costco (COST), will disclose details about their user base, as this is usually the long-term driver of success for the company. Meta, for example, discloses quarterly changes in Monthly, Weekly, and Daily Active Users. Amazon doesn’t, though occasionally it will disclose total Prime Members, but it leaves out key details like the activity of those members, the geographic location of those members, and the extent to which membership adds value to the enterprise. These are very significant aspects of the business Amazon knows, but its owners do not. Various investment research firms publish data on these topics, like estimating Amazon.com’s GMV or the spending habits of Prime Members, but Amazon keeps the truth to themselves. For Amazon.com and Prime, whose stand-alone value is dependent on factors other than just sales, and whose value as a part of the whole is to dig a moat and be a gate for the rest of Amazon, these segment results provided in Amazon’s financial statements come woefully short on giving investors and shareholders insight into the value of the company. This opacity contributes to the current lack of consensus on Amazon’s value.

In short, when sentiment goes south, investors seek certainty, and Amazon does not provide it. Does this open the door to opportunity or set a trap for the unwary? Let’s get informed.

Estimating Value – Models to Discard

Part of the issue with valuing Amazon is that the method we choose often reflects a pre-existing belief about the company, rather than helping to develop a thesis on the company. The best examples of this phenomenon are who I term the “Sum of the Parts Bulls” and the “P/E Ratio Bears.”

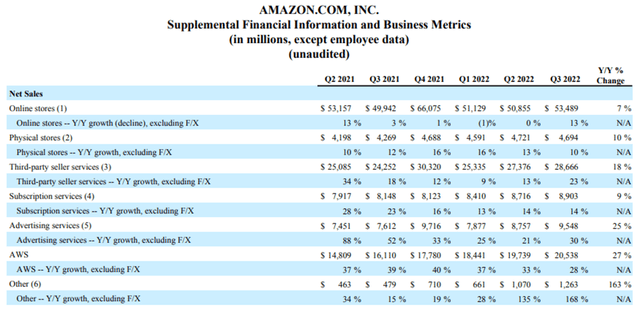

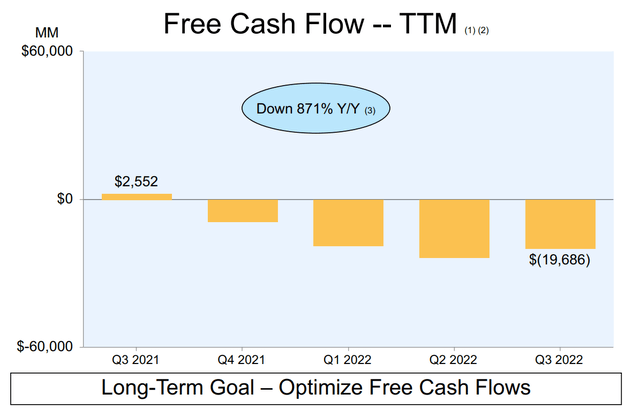

The “Sum of the Parts Bulls” evaluates each of Amazon’s individual segments in isolation and adds them together, usually ignoring the fact that they rely on each other for funds and customers. A typical phrase from a bull of this variety is: “The value of AWS is close to Amazon’s market cap right now, the rest of the company is free.” Let’s investigate that.

This looks pretty alluring, but would only matter if AWS were to be spun off (Author’s Calculation)

A valuation like the one above will point to the exciting conclusion that even if the rest of Amazon makes no money, worry not, because AWS will net you some sort of return. It will likely be made abundantly clear that the future growth assumption of 20% is conservative, the future operating margin of 25% is low, and a 20 multiple on earnings of a business such as this is on the low side. Imagine, they’ll say, if AWS on its own can deliver returns from this price, then any good news will send the price to the moon. This line of thinking is misleading because, as we know, Amazon takes profits from one segment and employs it in other segments. Unless AWS, or any other segment, were to be spun out into its own company, the value of Amazon is not just the sum of its parts; it’s an interdependent whole.

The “P/E Ratio Bears” sound similarly convincing. They simply have to point to the most commonly understood valuation metric in investing, the P/E ratio (how many times earnings a stock sells for), and say, “It’s too high.” And it certainly is! Amazon’s P/E ratio at the time of writing is around 76. Analysts estimate Amazon to grow at 10-15%, hardly deserving of a 76 multiple of earnings. But if we take a closer look, we can see that Amazon has always had a high P/E ratio, and with good reason, because it emphasizes free cash flow over earnings, at times even purposely reducing earnings to pay less taxes.

Jeff Bezos, in a 2004 letter to shareholders, wrote:

Why not focus first and foremost, as many do, on earnings, earnings per share or earnings growth? The simple answer is that earnings don’t directly translate into cash flows, and shares are worth only the present value of their future cash flows, not the present value of their future earnings.

Essentially, earnings, the “bottom line,” is an accounting metric, not a business metric. What earnings is most useful for is determining how much taxes a company owes to the government, not how much money the business generates. Most pertinently to Amazon, research and development expenses are included in accounting earnings. Amazon spends heavily on R&D, which has the dual benefit of reducing taxable earnings and spawning cloud computing titans from online booksellers. Earnings is clearly not the metric by which to measure Amazon. In fact, in Bezos’ very first shareholder letter, he famously wrote:

When forced to choose between optimizing GAAP accounting and maximizing the present value of future cash flows, we’ll take the cash flows.

When valuing Amazon, it’s best to ignore the P/E Ratio Bears and the Sum of the Parts Bulls and just skip straight to the cash flows.

Estimating Value – Free Cash Flow

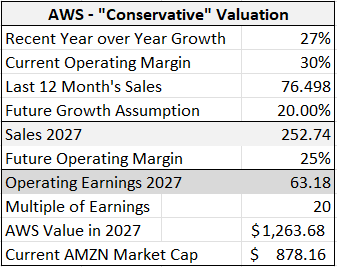

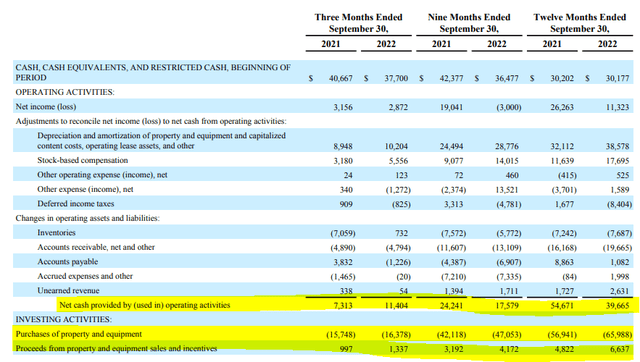

If Amazon is trying to maximize the present value of future cash flows, then that’s how investors ought to value the business. Unfortunately, this is the current state of free cash flow at Amazon:

Totally abysmal free cash flow (Amazon’s Q3 Earnings Presentation)

It’s worse than earnings. The big, bold long-term goal “Optimize Free Cash Flows” at the bottom only makes it worse. As is stated earlier, I’m assuming Amazon can pull it together and get back to positive free cash flow. Even with this assumption though, we need to find out if the price is right. To what extent is the recovery priced into the stock? It begins with free cash flow.

Firstly, let’s be clear on what free cash flow is. It is typically defined as the cash left over from business operations after all expenditures have been accounted for. The simplest way to derive free cash flow is to subtract capital expenditures (capex) from cash from operations on the cash flow statement.

Quick mental math reveals that the -$19,686 trailing twelve months free cash flow from Amazon’s Q3 presentation is derived from the reconciliation of the highlighted line items above. (Amazon’s Q3 Earnings Report)

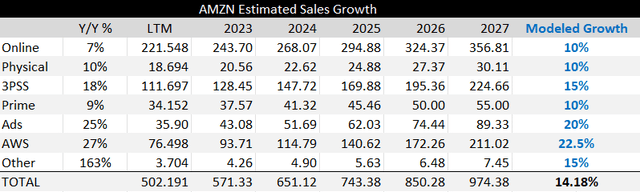

So, we must make assumptions based on how much cash Amazon is set to generate and how much of that will be put to use as capital expenditures. It begins with estimating sales growth. Fortunately for us, Amazon does disclose sales and sales growth of its segments. The following highlights what I consider to be conservative/fair assumptions by segment:

Sales growth by segment. Notice how the faster growing segments take up more of the revenue mix by 2027 (Numbers from Amazon Earnings Reports, calculation by author)

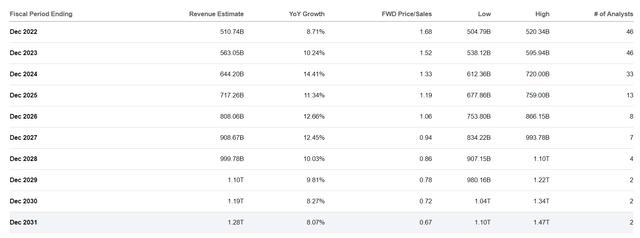

Using the assumptions above in blue, chosen because they are all less than growth in recent history and reasonable going forward, Amazon is set to have nearly a trillion dollars in sales by the end of 2027, for an annual growth in sales of 14.2% from today. Wall Street analysts come up with similar figures, seeing Amazon reach $1T in sales sometime in 2028:

Wall Street’s revenue estimates for Amazon – similar to our estimates above (Seeking Alpha)

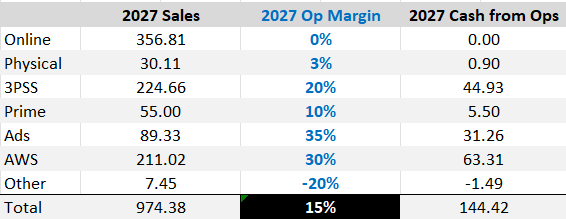

Clearly, margins are going to matter because Amazon’s free cash flow is currently negative; if the business were to continue as is, no amount of sales growth would improve Amazon’s value because it would not generate cash for owners. Unfortunately, margins are exactly where Amazon’s segment disclosure ends. The best we can do is make educated guesses. Based on the sales estimates above, here’s what I come up with. The assumptions are in blue, and the final operating margin highlighted in black:

If this is too optimistic or too pessimistic, I’d love to hear about it in the comments (Author’s Calculation)

Briefly, I’ll discuss why I chose these numbers, but it’s important to mention that, with the exception of AWS, the assumed operating margins of these businesses are less than an educated guess, and importantly, so are everyone else’s (unless they’re an Amazon insider).

I assumed that the online store would be able to break even, as it has in the past, but never be profitable for long because Amazon needs it to do the dirty work and dig its moat. The physical stores are not a big player, so I just put 3% on it and didn’t think too hard.

Third-party seller services took more work. I went to Amazon’s 3PS site and looked at the resources there. It turns out there is a fee calculator available. I tested a few different products, all of them charged a percentage referral fee and fixed fee to the seller (presumably for the privilege of selling on Amazon.com) that averaged around 15% of the selling price of the product. In addition, Fulfilled by Amazon (FBA) charged me at least 10% of the selling price for Prime delivery, packaging, and storage while attempting to upsell me on advertising. Since the seller fees are at no extra cost to Amazon and 85% of third-party sellers use FBA, I figured they make minimum 15%, more likely 20%, from the price of each item sold by an independent seller. I find this a safe assumption because Amazon easily increased the fees 5% when gas was over $100/barrel; a service that can increase prices that easily doesn’t stay low margin for long.

Prime was more difficult because it is estimated that Amazon spent $15B on content for Prime Video and Music alone in 2022, before costs of same-day delivery. We also don’t know exactly what expenditures are allocated to which segment (the income statement has a special line for fulfillment). I eventually just put 10% on it because, like 3PSS, the price was increased, and no one canceled their Prime subscription. It’s hard to stay low margin long with pricing power like that. The uncertainty in this segment is high, however.

Ads were as simple as looking at Google and Meta’s operating margins. They both make around 35% in online advertising, so I just applied it to Amazon. Amazon has the potential to have even higher margins, however, because, as we mentioned before, Amazon is where people go to shop, not scroll friends’ photos, or look up Amazon earnings reports (maybe that last one is just me).

AWS was the easiest because the operating margin is disclosed. All that was left was to determine whether the 30% margin would persist into the future. I eventually decided it would because the only businesses that don’t need cloud computing services are those big and wealthy enough to build their own system (like Microsoft and Google) or those who plan to stay exclusively brick and mortar. As we can imagine, those firms are few and far between. In addition, backlog is huge and Amazon’s market position is, once again, dominant. Microsoft (MSFT) is catching up, but the cloud market is growing quickly enough that there should be enough to share.

The last segment, “Other,” is totally impossible, but fortunately, its revenue footprint is currently low. I set the margin significantly negative because this is where unprofitable ideas are tested. As I said earlier, however, from “Other” came AWS, advertising, and 3PSS, so you never know what could happen. I decided to play it pessimistically, however.

That’s the thinking behind each choice. Everyone else who values Amazon (using free cash flow) makes similar assumptions, and unless we know the thinking behind each assumption, we really don’t know what their estimated fair value means. That’s why I’ve (rather lengthily) explained mine. It would be extremely useful if Amazon would disclose some more information about its segments. The lack of disclosure is probably hurting its share price, but they don’t seem to be about to do so.

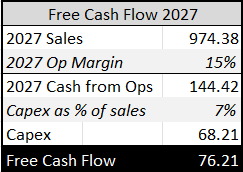

Having determined (very roughly) our 2027 operating margin and operating cash flow, we need to see how much capital expenditures to subtract. Recently, Amazon’s capex soared to its current $65B in the last twelve months; they’ve doubled the size of their operation since 2019. That $65B is close to 15% of sales – a considerable chunk of change. Historically, Amazon’s capex has been closer to 6-8% of sales. Going forward, we’ll subtract 6-8% of sales from cash from operations because it seems to be closer to what Amazon needs to maintain its operations than the current levels of expansive capex. 2027 free cash flow reconciliation is shown below:

A significant improvement on the current -$20B (Author’s Estimation)

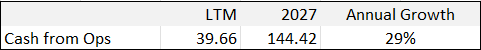

We could now apply a multiple to this free cash flow to determine a theoretical price of the stock, assuming no change in the number of shares outstanding. But what multiple would be appropriate? Personally, I consider a relatively safe multiple to be a multiple equivalent to the growth rate of the metric we’re using to value the company (i.e., a PEG ratio of one). In this case, because free cash flow is negative now, the growth rate could be skewed, so let’s check the growth rate of operating profit:

29% is number that could get investors excited (Author’s Calculation)

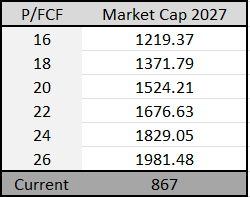

Cash from operations is set to grow at 29% a year, a considerable pace. Because free cash flow is starting from a lower point, its growth would be considerably higher, pointing to a multiple north of twenty. Historically, Amazon has traded anywhere from around 10x FCF in the early 2010s, to over 100x FCF just prior to 2022. To be conservative, I’m going to say that investors operating in a market where bond yields are similar to today’s and no catastrophe has occurred, would not mind paying something around 20 times free cash flow for Amazon in 2027. Our 2027 value then looks something like these:

Amazon’s current price compared to its 2027 price estimate based on what I consider conservative growth, margin and multiple assumptions (Author’s Calculation)

As we can see, Amazon looks to be about a double, or around 15% annualized return, based on our assumptions. That’s a reasonable return, especially for a blue-chip stock. It’s also probably the minimum required if we’re going to pick individual stocks over the index or other assets, like property.

It should be clear that this valuation is considerably more reliable than the P/E ratio or summing the parts because we treated the enterprise as a whole and measured it against the metric Amazon is explicitly targeting and all businesses aim to maximize: free cash flow. In addition to these advantages, we know what our inputs are; we know which variables matter and what is and is not priced into the stock price.

It should also be clear just how uncertain our outcomes are. Benjamin Graham wrote in “The Intelligent Investor” about methods like this, “dividing estimates by guesses and putting it to the third decimal place.” He’s right, of course, but when we’re buying stocks, growth stocks especially, it is important to know what assumptions are built into our price to avoid overpaying. That’s why I chose what I consider relatively conservative assumptions but would still look for a lower price before buying, just to be safe, because our assumptions are so uncertain. Graham would refer to this as a margin of safety.

Now we have an idea what a conservative fair value may be – around $85 a share – based on a required return of around 15% and using what information we can glean regarding Amazon’s operations.

Estimating Value – Sleuthing for Clues

The uncertainty of our fair value estimate requires more work because that value could be too high or more enticingly, too low. Let’s consider recent developments. Firstly, Amazon sold $8B of bonds, the proceeds of which could be used to buy back stock. Secondly, Amazon laid off 18,000 people, more than expected, and thirdly, Amazon is winding down unprofitable enterprises like telehealth and Alexa, the latter of which is said to be losing $10B a year. In addition, the USD is softening, causing foreign exchange headwinds to become a tailwind and commodity prices are declining, which should reduce Amazon’s costs. All these developments are not priced into the stock. If the Fed doesn’t overtighten and send the economy into a deep recession, Amazon could surprise us.

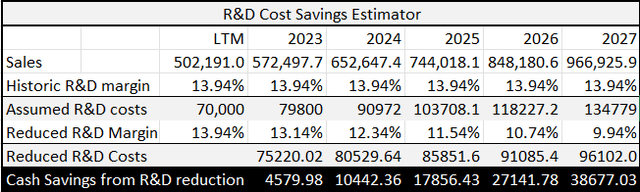

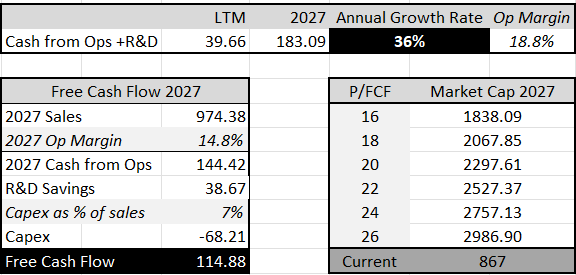

One interesting piece of information I’m extrapolating from these recent events is that, while we assume Amazon will get back on its cash flow feet based essentially on the normalization of capex spending and margins improving as inflation declines, we have not priced in any reduction of expenses that have long existed at Amazon, which seem to be targeted under new CEO Jassy. Research and development spend (“technology and content” on Amazon’s income statement) was $66B in the last twelve months, more than capex, close to 14% of sales. As investors, we have to wonder how much of that R&D spend is the next AWS and how much is the next Alexa. CEO Jassy seems to be curious about this as well. Significant cuts could mean our assumptions are too conservative; fair value could be considerably higher. I estimated the cash savings that would occur if R&D as a percentage of sales were to decline to 10% by 2027. The results are below:

Highlighted in black are the cash savings that would result from a decrease in the growth of R&D spending as a percent of sales. (Author’s Calculations)

A mild reduction percent of sales spent on R&D would result in cash savings of $10B for the year 2024, approximately the time when some of the cost cuts being implemented by Jassy should be fully completed. By the end of 2027, assuming around 10% of sales will be applied to R&D (still $96B), costs from R&D would be $38.7B less than what our fair value estimate above is building in. Let’s add that result to our free cash flow and fair value estimates:

How our free cash flow and fair value estimate change with R&D savings added back (Author’s Calculation)

As we can see, the results are significantly better. The annual growth rate of cash from operations is a monstrous 36%, while the operating margin would expand from the current levels of around 2.5% to nearly 20%. A business such as this would command high multiples, but even if we were to still use a twenty-ish multiple, Amazon suddenly starts to look like a triple from current prices, a 300% return by the end of 2027, for an annualized return of close to 25%. Even if Amazon were to cut legacy costs at half the rate I suggest, we’re still looking at a return of close to 20% per year. All of this is assuming the share count remains the same or similar from 2022 to 2027, when it is more likely that a business like the one shown above, would be interested in buying back its own stock. This explosive potential is not priced into the stock price at present.

Barring a large recession, most of the downside is priced into Amazon stock, while none of this potential upside is. This lends a favorable risk/reward profile to AMZN. Thomas Hayes, from hedgefundtips.com, is fond of saying, “The market is designed to cause the most amount of pain to the most amount of people at any given time.” This might be one of those times: with all the bad news and general bearishness, investors are selling in the hole (probably at a loss) and may have to watch as Amazon surprises the market and soars.

Risks

Amazon relies heavily on its gargantuan moat, dug by Amazon.com and Prime, to drive margins in advertising and third-party sales. If anything were to happen to its moat, like government regulation, Amazon would be a sell, at best a trade. As I stated before, however, this seems unlikely as the US federal government is struggling just to function and Amazon does not exploit customers – it actually benefits them. It will take a lot to break into Amazon’s business castle.

Amazon’s other major crutch is AWS. Without AWS, it would not be able to run all its other segments at a loss in times such as these. If cloud computing growth were to slow or margins were to drop, Amazon would be forced to operate its other segments more profitably (sounds funny, I know), potentially putting a leak in its moat. However, as mentioned above, the cloud market is dominated by Amazon and is expected to continue growing for at least the next five years. However, even if Amazon’s dominance were to deteriorate and growth slow, AWS would still churn out significant cash flow. In addition, third-party seller services and advertising services rarely require financial support from AWS, so reliance on AWS for profitability is declining.

The last risk is the same risk for every stock, a major recession. As we all know, market timing is incredibly difficult. Since I consider Amazon inexpensive now and intend to hold for at least five years, I don’t see this as risk, just a potentially reduced annual rate of return. This would likely be the case with any stock, so I don’t think too hard about it. If I did, I could miss the start of Amazon’s next bull run.

Conclusion

Due to Amazon’s opaque reporting, uncertainty as to its fair value is high. If we use free cash flow to value the business and require a minimum annual return of 15%, we find that Amazon is close to fairly valued at ~$85 per share. This valuation assumes Amazon gets back on its feet, but not much more. Through transparency in my assumptions, I hope readers can decide for themselves whether this is a fair evaluation.

The stock would be a hold or wait-and-see but Jassy seems to be aggressively cutting costs and the free cash flow potential of Amazon remains strong, as we demonstrated by slightly reducing R&D spending as a percentage of sales. As such, I believe the probabilities are on the side of Amazon outperforming in the longer term; however, uncertainty prevails for Amazon in the present so the stock price could go lower, in which case, I would relish the opportunity to lower my cost basis.

Disclosure: I/we have a beneficial long position in the shares of AMZN either through stock ownership, options, or other derivatives. I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it (other than from Seeking Alpha). I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.