Summary:

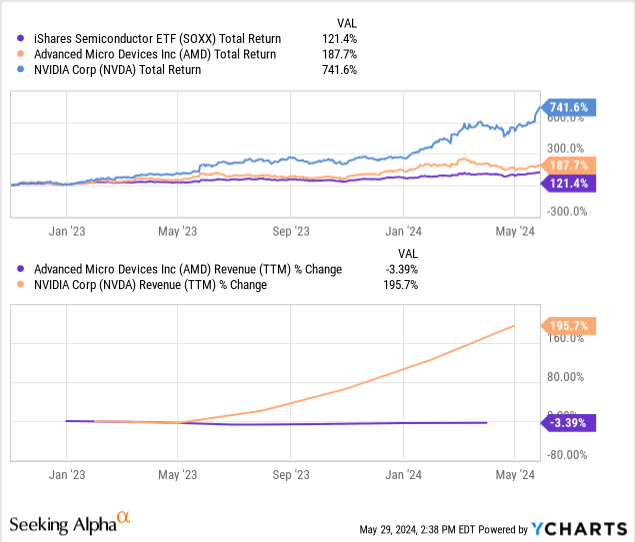

- AMD has been unable to grow revenues as Nvidia dominates the data center segment for AI accelerators.

- AMD and Nvidia hardware have a few key differences and overall Nvidia simply provides better products.

- AMD’s foray into FPGAs could lead to a unique competitive positioning and provides some reason for optimism.

JHVEPhoto

Prelude

The launch of ChatGPT is widely acknowledged as the catalyst that set off the rocket ship journey that semiconductor stocks have been on recently. It illustrated to the world the potential of AI applications. Corporations raced to determine how to implement AI wherever possible, and this led to a surging demand for the hardware required to run AI at scale. Revenues for Nvidia (NVDA), the leading AI hardware provider, have skyrocketed as a result.

Companies broadly have two options for AI; to run it from on-premises data centers or to rent capacity from the cloud. The cloud represents a growing majority of overall data center compute, which is broadly shifting from traditional CPU to accelerated GPU workloads, so CapEx from the three major CSP’s (Cloud Service Providers) is flowing to Nvidia’s income statement. Large enterprises like Meta (META) or Tesla (TSLA) have also been major buyers of GPUs to build out on-prem data centers. Demand for Nvidia hardware has come from all angles, and throughout all of 2023, the company was supply constrained. The CoWoS advanced packaging within Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company’s (TSM) 4N process node quickly became a bottleneck amid surging demand. As a result, TSMC has been aggressively expanding capacity, but Nvidia’s Blackwell platform is still expected to be supply constrained.

As companies grappled with this constraint, the natural option was to find alternatives. Advanced Micro Devices (NASDAQ:AMD) offers a line of accelerators that are widely accepted as the best alternative to Nvidia’s Hopper platform. AMD’s flagship accelerator, the MI300X, also depends on TSMC’s CoWoS packaging to stitch together logic and memory. In mid-2023, TSMC said it expected half of its CoWoS supply to go to AMD. Despite this, AMD has drastically underperformed Nvidia and has just barely outperformed the Semiconductor index since November of 2022. The reason for this underperformance is that, well, AMD can’t grow its revenues! Amidst the most intense demand surge for semiconductors in recent history, AMD is being entirely left behind by its closest competitor, Nvidia.

Product Differences

To evaluate why Nvidia has been winning and AMD hasn’t, let’s talk through some key differences between Nvidia and AMD hardware in the datacenter. These include 1) chiplet approach, 2) CPU instruction set architecture, and 3) software.

Chiplet vs Monolithic

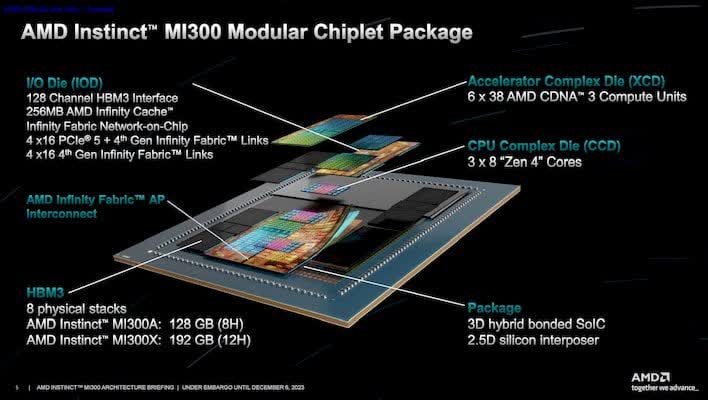

AMD’s MI350X is built with a chiplet approach. This approach involves segmenting out independent components of a chip and building them separately. CPU cores, GPUs, I/O dies, and HBM memory will be fabbed separately and unified on a common substrate. AMD then uses its “Infinity Fabric” networking to connect these chiplets together, which is similar to a PCIe bus but with more memory bandwidth.

hothardware.com, AMD

The chiplet approach brings manufacturing costs, which scale with transistor count, down dramatically for the whole chip. Further, it allows more flexibility since the company can re-use, or “harvest”, IP across different chip generations. If AMD wants to launch a product with a next gen GPU, it can package it onto a new chip without needing to update all the other chiplets.

Contrast this with Nvidia’s approach which involves designing the accelerator, I/O and local memory together within the same unit. The GPU is then packaged together with high bandwidth memory (“HBM”) and bundled into a unified compute unit. The Nvidia B100 has billions of transistors so it’s very costly to manufacture and has a higher risk of defects than a chiplet design. Keep in mind Nvidia’s Hopper and Blackwell chips aren’t truly monolithic; HBM still sits separate, but they are more monolithic than the MI300x.

Nvidia’s approach targets the whole data center rack. NVLink networking enables customers to treat entire racks of GPUs as one compute unit. Mixed with the capabilities of CUDA to redirect data around a datacenter to oversubscribe GPUs and utilize unused capacity. With this approach an entire data center becomes basically one entire AI factory as Jensen calls it. Workloads can be distributed across an entire data center and parallelized across different GPUs. Further, Nvidia’s adopted a chiplet-esque approach with H200/B200 which both include a co-packaged Grace CPU.

To my knowledge, AMD doesn’t yet have this capability. So far, Nvidia’s approach of treating the entire data center as a factory to run training and inference is winning over AMD’s approach of more cost-efficient individual chips.

ARM vs x86, CPU Differences

Both the H200 and MI350X platforms feature GPUs and CPUs. One benefit of a monolithic over a chiplet approach is reduced power consumption because on-chip data transmission is more efficient. For Nvidia, this is compounded by the Grace CPU architecture, which is built on the ARM Holdings (ARM) reduced instruction set architecture. Zen cores on the other hand are built on the x86 complex instruction set architecture. One key benefit of ARM is energy efficiency, so Nvidia’s ARM CPU and monolithic design contribute to a better TCO (total cost of ownership) compared to the value reaped from the chip. According to Nvidia, $1 spent on H100 today will contribute to $5 of revenue over 4 years for customers.

With power consumption becoming an increased concern for data center operators, I suspect Nvidia’s value will continue to shine through over AMD here.

Software: CUDA vs. ROCm

Nvidia has generally kept its hardware, software, networking stack similar to Apple’s (AAPL) “walled garden”. Nvidia is the one-stop shop for customers, they will provide everything. But you will pay up for it. The experience has historically been superior enough to all alternatives that customers are willing to stay in the walled garden, but the industry is showing signs of wariness against this lock-in. AMD and Intel (INTC) both provide general purpose GPUs but they share the measly leftovers of Nvidia’s roughly 80% market share. On the other hand, major CSPs and large enterprises like Meta and Tesla have all begun designing custom application specific accelerators. Despite the increasing competitive threats, Nvidia remains dominant. Why?

Superior performance. As many analysts have pointed out, Nvidia’s hardware is arguably no better than AMD or Intel’s. On paper, the specs are quite similar. Nvidia runs away from the pack when it comes to the utilization of the hardware, though. CUDA allows developers to more effectively utilize the hardware. Most times, GPU cores can process data quicker than it can be retrieved from memory, so they need to be ‘oversubscribed’. This means we load more data into local cache memory in specific cores than they can process at once. Once they finish one task, there is another one waiting for them to start while more data is being retrieved from memory. CUDA is purpose built for Nvidia hardware. To program an AMD GPU, you need a developer that knows how ROCm works and is able to convert from CUDA to ROCm (if you are switching from Nvidia to AMD hardware).

The ZLUDA project helps developers port CUDA code over to a ROCm platform, but it’s not as simple as clicking a button and you’re done. CUDA remains superior because of the rich ecosystem Nvidia has built. CUDA offers extensive libraries to build AI, a huge installed base of hardware, a very experienced force of developers, and better documentation than ROCm. It’s easier to find and hire CUDA developers, and the extensive documentation / libraries makes it easy to build around CUDA. ROCm has a lot of catching up to do.

Summary

Overall, AMD does not look to be making any meaningful progress against Nvidia in the data center. While the MI300X ramp is progressing well, AMD has not shown the incremental revenue growth that Nvidia has. Nvidia has better growth, better margins, a stronger competitive positioning, and a much wider moat than AMD. Data center is a large part of the story, so this is not great for AMD investors yet still there is reason for optimism.

The Not-So-Hidden Bull Case

It is no secret that AMD made a big bet on FPGAs (Field Programmable Gate Arrays) with the Xilinx acquisition. FPGAs exist in the middle of a spectrum that includes general purpose CPUs and GPUs on one side and ASICs (Application Specific Integrated Circuits) on the other. ASICs are completely purpose built for a specific function, while general purpose hardware is built to offer overall the best performance possible. General purpose hardware would likely underperform an ASIC in the specific use case that ASIC is built for.

FPGAs can be rewired after initial manufacturing for specific use cases and changed for other purposes. This builds upon AMD’s modular approach as they can build a common FPGA baseboard and can subsequently make numerous custom versions of that for different hardware end uses. Whether it will be I/O optimized for data center, power efficiency optimized for mobile SoC’s, or latency optimized for AI PC’s, AMD can offer solid hardware for many different use cases. AMD’s competitive positioning may become more of a one stop shop for everything AI from the data center to the edge, instead of Nvidia’s position as the vendor for “AI factories”. AMD’s modular approach and flexibility provided by FPGAs allows AMD to provide quite competitive hardware for a fraction of the cost. If AMD can drum up enough growth by either capturing new demand or taking share from Nvidia, the company could meaningfully expand its operating leverage while solidifying itself as the next best option to Nvidia in the lucrative data center segment.

Takeaway

While AMD is far smaller than Nvidia in terms of market cap, there is still some reason for investor optimism. The industry is undergoing a historically large infrastructure buildout and although AMD is behind Nvidia right now, the rapid growth of the broader industry is likely to support them. Furthermore, the company is positioning itself as a more cost competitive offering compared to Nvidia’s costly machines. The AI industry is still quite nascent and rapidly evolving, but the industry growth is fundamentally bullish. However, I expect AMD to underperform semis in the near future which are already priced quite rich. For that reason, I rate AMD a Hold at current levels as I do not see a lot of opportunity in a company trading at 10x sales while showing no revenue growth for a year and a half.

Analyst’s Disclosure: I/we have no stock, option or similar derivative position in any of the companies mentioned, and no plans to initiate any such positions within the next 72 hours. I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it (other than from Seeking Alpha). I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.

Seeking Alpha’s Disclosure: Past performance is no guarantee of future results. No recommendation or advice is being given as to whether any investment is suitable for a particular investor. Any views or opinions expressed above may not reflect those of Seeking Alpha as a whole. Seeking Alpha is not a licensed securities dealer, broker or US investment adviser or investment bank. Our analysts are third party authors that include both professional investors and individual investors who may not be licensed or certified by any institute or regulatory body.