Summary:

- Warren Buffett’s initial investment in Apple in 2016 coincided with strong revenue growth, free cash flow, and undervalued buybacks.

- Apple’s market cap has grown significantly since 2016, with a current Price/FCF multiple of about 30, raising concerns about future returns on buybacks.

- Revenue and cash flow growth also haven’t been as steady as the market for smart, electronic devices has had time to saturate.

- While the brand and products are still solid, a worse value picture reduces AAPL to being a Hold for now.

Marat Musabirov/iStock via Getty Images

Always popular, Apple (NASDAQ:AAPL) has received even more attention since Warren Buffett sold half of Berkshire Hathaway’s (BRK.A)/(BRK.B) stake this year. I’ve considered writing my own opinion of Apple for some time, but I could never quite find a good reason to do so. Buffett’s move has intrigued me, and I decided to take another look myself.

I have dissected the investment opportunity that Buffett faced in 2016. I’ve done the same for Apple today. The contrast between these pictures explains why he reduced his stake. While Uncle Warren is our barometer of Apple, the deduction and interpretation is my own. Join me on this trip into his mind, and see why I consider AAPL a Hold.

Berkshire’s First AAPL Position

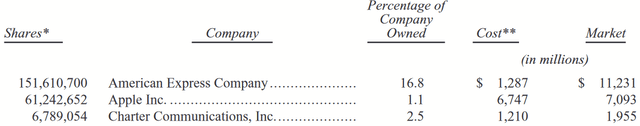

A timeline of Buffett’s AAPL trades shows his earliest position occurring in 2016. For the full-year results, AAPL accounted for 1.1% of the Berkshire portfolio at that time.

These initial trades, adjusted for the 4:1 stock split that occurred in 2020, came to a cost basis of $27.54 per share, with about $6.7B in capital committed. Buffett has been known for his avoidance of tech stocks throughout his life, and AAPL was one of those. Its IPO was in 1980, with a split-adjusted price of $0.10 per share! With more than three decades to invest in it, and some might think he “missed out.” What finally convinced him to give AAPL a shot?

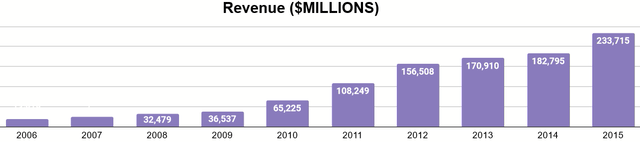

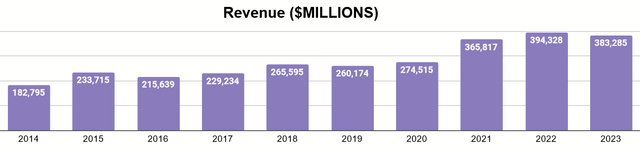

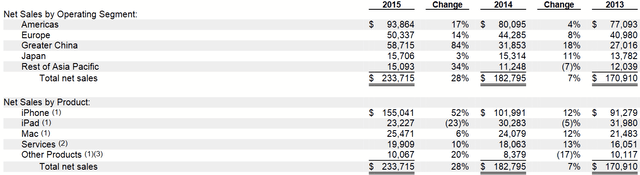

Let’s look at the information he would have had. In the decade prior, Buffett would have observed impressive revenue growth for Apple, going from $19.3 billion in 2006 to $233.7B in 2015, more than 10x in just revenue! Not only that, but this revenue growth was not impeded by the Great Recession in 2008. Ben Graham taught value investing to Buffett as though another Great Depression could always happen, so this proved the strength of Apple’s business model to him.

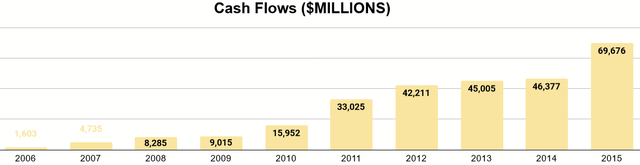

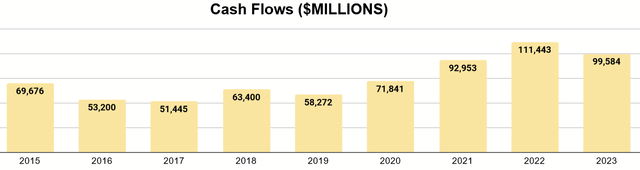

Of course, we want to see what happened with free cash flow as well, as we know Buffett would have been looking at that. Above, I have included the net outflows from M&A to give an adjusted FCF figure, but it’s an impressive explosion of growth.

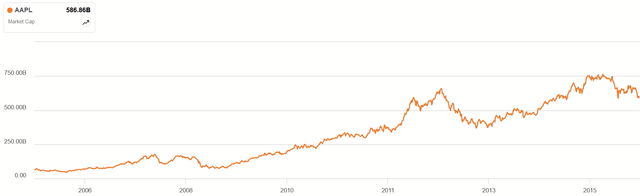

Market Cap History 2006 – 2015 (Seeking Alpha)

As these disclosures are for fiscal years ending September, we have to consider what picture Buffett would have been seeing in Berkshire’s first quarter of 2016. AAPL ended calendar 2015 on a market cap of $587B, despite generating $69.7B in cash for that year and showing signs of growth. That’s a multiple of about 8.4 for what was a rapidly growing business. Not only had that occurred, but something else had changed: They lost Steve Jobs in 2011.

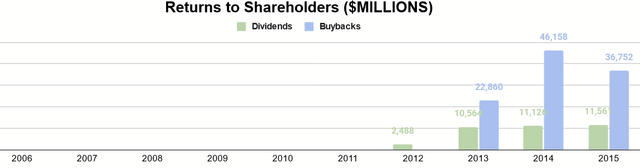

In 2012, Buffett recalled how Jobs was opposed to buybacks, as he wanted to keep cash on hand for large acquisitions. Thus, Apple was not returning anything to shareholders through dividends or buybacks back then.

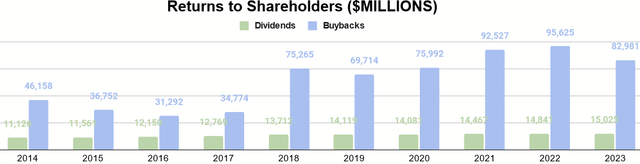

By 2016, Apple had been distributing dividends for four years and doing buybacks for three. With FCF per share growing from the business itself and the buybacks at low multiples, Buffett had exactly what he likes: free cash flow, growth, dividends, and undervalued buybacks.

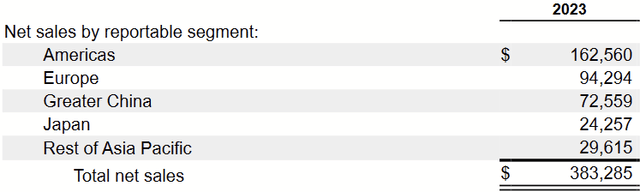

2015 Revenue Breakdown (2015 Form 10-K)

As these cash flows were primarily driven from its strong iPhone product, supported by iPad and Mac sales with their cult followings, I think Buffett had reason to feel good about these cash flows going forward. Buybacks for undervalued stocks were essentially reinvesting into the same business for a higher return on capital, and Apple was now showing a preference for putting most of their FCF into that.

Apple During The Sale

Berkshire would go on to acquire more shares after 2016 and build a much larger position, just over 900M shares. Based on what was reported in 2021 (pg. 7), the cost basis was no more than $33 per share.

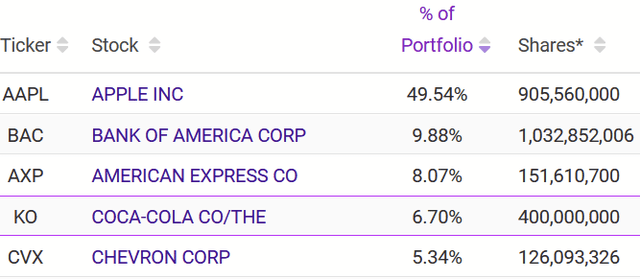

Q4 2023 Holdings (valuesider.com)

As we entered 2024, Berkshire was sitting on about 905M shares of AAPL, almost half the market value of the stock portfolio.

AAPL 10Y Price History (Seeking Alpha)

Buffett had already sold 10M shares in Q4 2023 (a small portion), as AAPL had reached new highs. Some investors might do this to raise a little cash to take another position elsewhere. Still, it seems that Buffett was thinking harder about the whole position. In Q1, he sold about 116M shares, and this move was addressed by Buffett in the shareholder meeting.

Interestingly, most coverage on his remarks spoke to his wish to avoid higher taxes in the future. Yet, Buffett had opened those remarks by specifically stating that people focus too much on trying to avoid taxes. In hindsight, I see a warning that he intended to sell much more of AAPL in Q2, but not to worry about the tax impact. Q2 saw the sale of about 389M shares, leaving the current position at about 400M.

If we look at the past decade of Apple’s financial results, differences become clear. Revenues have trended toward growth, but it’s not an uninterrupted streak anymore. It’s also not nearly as vertical as 2006-2015.

The same is true of the cash flows. On my adjusted basis, FCF is higher, but had some ebb and flow. Overall, the growth picture has not been as optimistic, but the long-term trend is still there, and cash flows don’t turn negative.

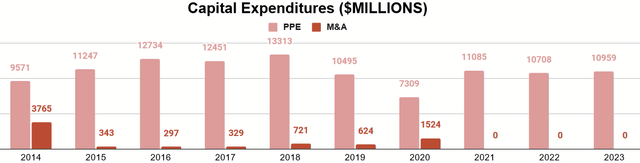

Capex has remained very stable, even has Apple grows. Additions to Property, Plant, and Equipment peaked at $13.3B in 2018 and typically remains around $11B. M&A remained low and ceased after 2020. As of their Q3 Form 10-Q for this year, YTD figures remain comparable. Thus, I think Apple shows a very strong ability to scale, allowing for healthy FCF margins.

Revenue by Region (Q3 FY 2024 Form 10-Q)

Revenue by region shows a similar story, with concentration in healthy economies such as those of the Americas and Europe and a footprint in Asia.

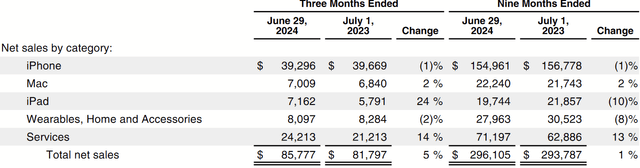

Revenue by Product (Q3 FY 2024 Form 10-Q)

By product, the iPhone still dominates around half of revenues. Services is the one line that enjoys a much larger share of revenue than it did when Buffett first bought.

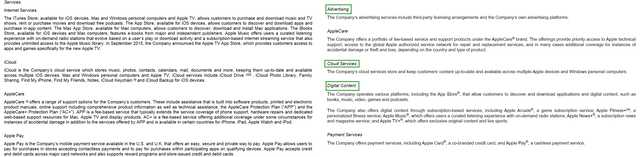

Apple’s Services (Left: 2015 Form 10-K, Right: 2023 Form 10-K)

Apple was able to leverage and flesh out the ecosystem that was created once the iPhone experienced mass adoption. Not only were customers purchasing iPhones, but this converted to more revenue from the purchases in the App Store, the use of iCloud, and the emergence of their own advertising business.

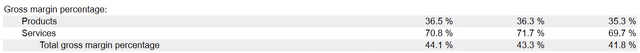

Services also enjoy much better gross margins than their hard products. They are something of a stabilizer if iPhone sales are slower.

These mostly sound like good things, and yet Buffett still sold about half the position this year, while justifying it with his view that it’s better to lock in a gain and pay the tax than worry too much about delaying a tax impact. In those same remarks, he even stated he thinks Apple is a wonderful business and worth keeping at least some stake. What could have motivated him to sell?

AAPL Market Cap 10Y History (Seeking Alpha)

For one, let’s consider where the market cap is now. Under $600B in 2016, it now stands over $3 trillion. While 2016’s Price/FCF was about 8.4, today’s is about 30.

As this multiple increased, so did the buybacks. While they greatly enhanced AAPL’s growth of FCF per share when undervalued, they haven’t abated. As the multiple expands, the return on capital for each buyback becomes less and less, perhaps even being value-deletive. With nearly all of FCF being devoted to buybacks now (and no one like Jobs to spit on the idea), the long-term returns of individual shares are in question.

30 is a high multiple, and very few businesses could be said to be undervalued when priced that way. Even ones with truly special products like Apple run into ceilings on growth when they become large enough, and Apple is the largest company in the world if measured by market cap. Measured by revenue, it’s the seventh largest.

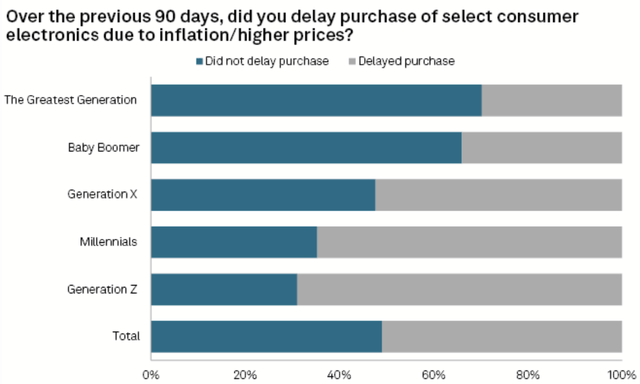

Smartphones and related devices have a cycle of use and replacement. S&P Global published an article, speaking to how higher interest rates have resulted in delays for device renewal. As almost nobody expects rate cuts to occur as quickly as hikes did, new sales of Apple devices could be strained for quite a while.

The one potential boon is the same as every tech stock: AI. As most of their revenue comes from selling devices, this would likely benefit their Services line. What doors will AI open for Apple that aren’t already open? I find that hard to tell. Rather, I think AI just forces Apple to make sure that it can produce devices that run and work with AI well. Where Google (GOOG) and Palantir (PLTR) are software-driven and work with data, AI significantly magnifies the value their basic product can create. I don’t see Apple being in nearly the same position, and perhaps Buffett agreed.

Valuation

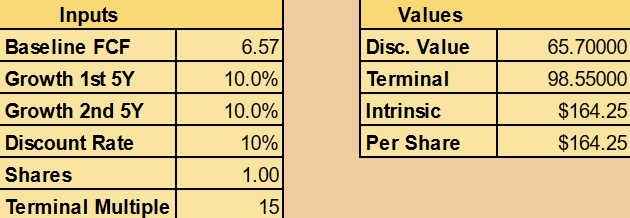

Based on all of this, I am going to value AAPL with a Discounted Cash Flow model. I’ll make the following assumptions:

- $6.57 of FCF per share

- 10% CAGR for the decade

- Terminal multiple of 15

Assuming $100M in annual FCF (consistent with the last three years of the adjusted figure in my data), the current shares outstanding get us to $6.57 in FCF per share.

A CAGR of 10% for the next decade is what I believe to be the most optimistic, given how smartphones and related devices have already been widely adopted and higher interest rates may extend the cycle. Moreover, buybacks at these high prices could even slow the growth of FCF per share.

A terminal multiple of 15 is about half the current one and shows what can happen if the market contracts over time in response to slower growth. I suspect Apple’s reputation is such that it’s unlikely to be in the single digits again, however.

Author’s calculation

Priced for a 10% average return (typical of a market index), that suggests a fair value is about $164 per share, not far from where the price was while Buffett was selling. As I think this is optimistic, there’s more room to disappoint. Apple just lacks the margin of safety that it had in 2016.

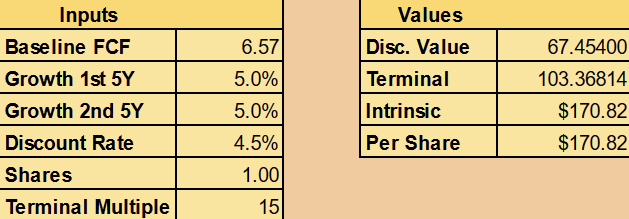

Possible DCF for Buffett

As Buffett is known to compare investments to the 10Y Note, it’s possible he has even lower growth assumptions about Apple himself. With its rate around 4.5% in Q2, tweaking the DCF shows that Buffett may be expecting single-digit growth (if his other assumptions are similar to mine).

Conclusion

Apple is a solid company, but in recent years, sales and cash flows have grown but less steadily. Buybacks occur for nearly all of FCF and occur at multiples reaching 30 and offer less ability to magnify shareholder returns. They even risk weighing down the intrinsic value of the shares. The market of smart, electronic devices appears more saturated since their invention and prone to cycles of renewal. As one of the largest companies that exists, I think Apple is more likely to be affected by cycles going forward.

Are we getting a good price for AAPL by buying today? I don’t think so. I think today’s price may only be close to a fair value, depending on one’s required rate of return. Buffett himself didn’t squirm at the valuation to the point that he shed the entire position in Q2, but a sale of that magnitude highlights what his upper limits may be.

Given the difference in the mathematics between 2016 and today, it’s not hard to see why, and that’s why I think AAPL is in a Hold phase until the price or the value proposition change drastically.

Analyst’s Disclosure: I/we have no stock, option or similar derivative position in any of the companies mentioned, and no plans to initiate any such positions within the next 72 hours. I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it (other than from Seeking Alpha). I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.

Seeking Alpha’s Disclosure: Past performance is no guarantee of future results. No recommendation or advice is being given as to whether any investment is suitable for a particular investor. Any views or opinions expressed above may not reflect those of Seeking Alpha as a whole. Seeking Alpha is not a licensed securities dealer, broker or US investment adviser or investment bank. Our analysts are third party authors that include both professional investors and individual investors who may not be licensed or certified by any institute or regulatory body.