Summary:

- Apple’s shares earned a spectacular 30.5% compound annual return for the decade ended 2021.

- Nearly 85% of operating cash flow is being spent buying shares.

- What started off as a very good thing ultimately becomes perhaps less of a good thing at high prices.

- We’d prefer a more flexible capital policy,buying shares when they are cheap and sending special dividends to shareholderswhen they are not.

Justin Sullivan

The following segment was excerpted from this fund letter.

Apple Inc. (NASDAQ:AAPL)

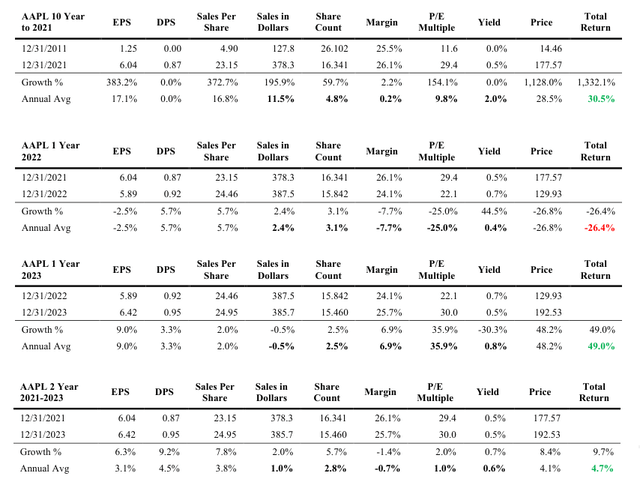

Apple’s shares earned a spectacular 30.5% compound annual return for the decade ended 2021. It was not a small enterprise at the outset of the decade, earning $33 billion on $128 billion in sales and valued at $377 billion, or 1 1.6x earnings by Mr. Market.

To produce a ten-year 30.5% annual return on what turned out to be 11.5% annual sales growth (nearly tripling), more than blistering top line growth was involved in the outcome.

First, Apple began paying a dividend in 2012, which contributed 2.0% to annual return. In viewing the table for the decade, one might fairly ask how no dividend at the outset and a 0.5% dividend yield at the end can produce 2% per year. As discussed earlier, a dividend yield is at a point in time. For much of the decade Apple’s shares were cheap. They sported an 11.6x P/E multiple at the end 2011 for example (and less than I Ox net of net cash). The stock took off in the back half of 2019 through year-end 2021.

From 2012 to 2020 Apple paid roughly a quarter of annual earnings as dividends and because the stock was trading generally for a low-teens multiple, the yield was high. By 2021 the multiple blew up to 29.4x (contributing almost 10% to annual returns) and the company also decided to hold the payout to about 15% of annual profit. Hence on a much higher P/E and lower proportionate distribution the dividend yield collapsed to 0.5%.

I’m not sure how conscious the decision was to shrink the dividend payout. Annual increases in the dividend rate rose by a nickel a share over eight of the ten years after the dividend was first paid. In two of the years the bump in rate was a few cents higher. So why shrink the payout rate, particularly since profit margins were stable to very modestly rising? What use did and does Apple have for their retained earnings?

For one thing, research and development has marched higher over the past twelve years, rising not only in dollar terms as the business grew but also as a proportion of rising sales, from roughly 3% of sales on average to 7.5% more recently. Capital expenditure needs of the business are tiny, whether for maintenance or growth. R&D and advertising drive the business. But Apple found an even larger use of surplus capital, which for years contributed mightily to shareholder return – share repurchases.

A year after Apple began paying a dividend, it ramped up its share repurchase program in a very big way. Instead of buying back approximately $2 billion a year as they did in 2011 and 2012, about 4% of cash flow from operations, in 2013 they bought back almost ten times that amount and averaged about half of cash from operations for the next five years. From 2018 through 2023 Apple has repurchased almost $470 billion of their shares against $560 billion in cash from operations. Nearly 85% of operating cash flow is being spent buying shares. The P/E was still only 16x in 2019. Over the decade in review from 2011 to 2021, Apple bought back 37.4% of its outstanding shares, or close to 4.8% of their shares each year (over the years with large repurchases).

The problem becomes price. What started off as a very good thing, buying shares when they were cheap after taking care of capital needs and R&D, ultimately becomes perhaps less of a good thing at high prices. Over the last two years, Apple’s revenue growth ground nearly to a halt, only growing 1% per year. R&D is being taken care of at 7.5% of sales. Apple continued to repurchase mammoth amounts of stock, averaging $84 billion a year for the last two years against an average $111 billion in cash from operations.

By paying multiples pushing 30x earnings (a 3.33% earnings yield), you don’t get as much bang for the buck. Spending three-fourths of cash flow retired the share count by 2.7% a year from 2021 to 2023. The stock produced a 4.7% average annual total return over the two years but doing so required nearly all incremental firm resources. As large indirect shareholders through Berkshire’s ownership of Apple shares, we’d prefer a more flexible capital policy, buying shares when they are cheap and sending special dividends to shareholders when they are not. If sales growth fails to recover to at least 7% annually, the multiple is certain to shrivel from today’s 30.0x. To my mind, Apple is worth far less than its $3 trillion valuation on $400 billion of slow-growing sales producing profits of just over $100 billion.

|

SEC-registered investment advisory firms are now required to disclose 1-, 5- and 10-year returns, or the time period since performance composite or portfolio inception, if shorter. The new rule seeks to prevent “advertisers” from cherry-picking time periods that make returns appear more favorable. As short- and intermediate-term returns change frequently due to beginning and endpoint sensitivity, we have chosen to disclose all yearly intervals from the current 1-year return all the way back to inception. Intra-year periods will likewise be shown annually back to inception. Better, in our opinion, to provide more data than less. We are augmenting the mandated disclosure with the full data set – not to confuse – but if we must provide a few defined numbers, to the extent anybody uses them in decision making, we want you to have the information we’d want if our roles were reversed. The yearly return intervals are italicized and shaded in blue. Information presented herein was obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy, completeness and opinions based on this information are not guaranteed. Under no circumstances is this an offer or a solicitation to buy securities suggested herein. The reader may judge the possibility and existence of bias on our part. The information we believe was accurate as of the date of the writing. As of the date of the writing a position may be held in stocks specifically identified in either client portfolios or investment manager accounts or both. Rule 204-3 under the Investment Advisers Act of 1940, commonly referred to as the “brochure rule”, requires every SEC-registered investment adviser to offer to deliver a brochure to existing clients, on an annual basis, without charge. If you would like to receive a brochure, please contact us at (303) 893-1214 or send an email to csc@semperaugustus.com. |

Editor’s Note: The summary bullets for this article were chosen by Seeking Alpha editors.