Summary:

- Apple has a history of antitrust litigation, including a case involving e-book price-fixing and a lawsuit against Qualcomm.

- The US Department of Justice (DOJ) has filed a new antitrust suit against Apple, but it is weak and lacks evidence of Apple’s monopoly power.

- The requested remedies in the suit are mild and are unlikely to have a significant impact on Apple’s revenue.

hapabapa/iStock Editorial via Getty Images

Apple (NASDAQ:AAPL) admittedly has a checkered past when it comes to antitrust regulation, both in this country and the EU. Often, Apple’s management have not seemed to get what antitrust regulation is about or how to comply with it. In the process, Apple has wasted millions in legal fees. However, defending itself against the latest antitrust suit brought by the US Department of Justice (DOJ) will not be a waste. I consider the suit surprisingly ill-conceived and weak.

Remembering Apple’s antitrust past (so we won’t be doomed to repeat it)

On March 21, 2024, the US Department of Justice announced a suit against Apple (AAPL) under the Sherman Antitrust Act. Before I delve into that, I wanted to touch briefly on important moments in Apple’s antitrust past.

I have two motives for doing this. First is to acknowledge that Apple doesn’t have completely clean hands when it comes to antitrust compliance, and the second is to pre-empt objections to what I’m about to say about the DOJ’s latest antitrust suit against Apple.

This time I’m going to defend Apple and accuse the DOJ of a very weak case. I’m not doing that because I’m an Apple fan boy who always takes Apple’s side. In fact, I think I have a pretty good track record when it comes to Apple’s antitrust litigation.

But first, a little history. This isn’t the first time that Apple has been sued under Sherman. Apple was sued in April 2012 for conspiring with book publishers to fix prices for electronic books. This had been part of Apple’s attempt to bolster iBooks on iPad.

After reading the government’s complaint, it was painfully obvious to me that Apple had violated Sherman in a rather blatant way by colluding with publishers to fix prices. Apple’s justification was that it was trying to break the monopoly of Amazon (AMZN), which it claimed engaged in predatory pricing in order to maintain its e-book monopoly.

The judge in the case, Denise Cote, made it very clear that the government did not welcome such antitrust vigilantism. It was not for Apple to decide what was illegal monopoly. Monopoly per se is not illegal under US law, nor is charging prices below cost, as it was alleged Amazon had done.

Apple appealed all the way to the Supreme Court and lost in 2016. I wrote about Apple’s antitrust reality distortion field and the lost appeal. Throughout my coverage of the case, I felt that Apple was poorly served by its legal counsel.

The publishers with whom Apple colluded immediately settled with the DOJ and got their hands slapped. Apple, on the other hand, got to have a court-appointed antitrust compliance monitor installed.

The lesson that Apple seemed to learn from the e-book experience is that if you want to go after a monopolist competitor, best to have the government on your side first. At least, that seems to have been the approach in Apple’s next major antitrust-related litigation, its suit of Qualcomm (QCOM) in 2017. This was filed almost simultaneously with an FTC suit against Qualcomm based on nearly identical premises.

At the time, Qualcomm certainly seemed vulnerable. It had been investigated by the China National Development and Reform Commission, which forced it to modify certain business practices in a 2015 settlement. Qualcomm was next investigated by the Korea Fair Trade Commission, which I described in an article on SA.

The general criticism was that Qualcomm threatened to withhold its chips unless the handset makers agreed to its patent licensing terms. This was the so-called “no license, no chips” policy. Part of the abusive character of the licensing terms was that Qualcomm required licensing a broad portfolio of patents, even if they weren’t being used by the handset maker or in Qualcomm’s chips themselves.

Included in the bundle of patents were so-called standards essential patents, which are supposed to be licensed on the basis of fair, reasonable, and non-discriminatory (FRAND) terms. By only licensing the bundle, rather than individual standards essential patents, Qualcomm could effectively circumvent the FRAND requirements.

These and similar complaints formed the basis of the FTC’s and Apple’s lawsuits. Apple bitterly resented paying the licensing fees, which Apple considered an unfair tax. It was clear from the text of the two suits that Apple and the FTC had cooperated and viewed Qualcomm’s licensing policy the same way.

However, I was never convinced by Apple’s and the FTC’s legal arguments, as I discussed in an SA article. As unusual as it was, there was nothing in US antitrust law that made it illegal for Qualcomm to license its intellectual property in the way that it was doing.

Qualcomm eventually defeated Apple and the FTC. Once again, Apple had launched a crusade against a “monopolist” competitor and come up short.

Apple was forced to pay back royalties, and it entered into a multi-year supply agreement for cellular modems. This agreement was recently extended through 2026.

A third instance of Apple involvement in business regulation, I’m bringing up because it bears directly on the recent DOJ suit. This involves the EU Digital Markets Act (DMA) and Apple’s recent decision to comply with it.

Let me make it clear that I consider the DMA extremely misguided and harmful. It arrogates to the European Union Competition Commission the power to regulate the private on-line stores of companies such as Apple as if they were a broader form of commerce.

This regulation can take the form of specifying the types of products to be carried in the stores and the prices to be charged. As I described in an article on the DMA and its impact on Apple, the legal theory is that the large online stores are “gatekeepers” too large to be left unsupervised.

Normally, competition regulators only interfere with a company’s business after a violation has been legally established in court. Not in the EU, as this quote from the EU announcement of the DMA attests:

“The purpose of the digital single market is that Europe gets the best companies and not just the biggest. This is why we need to focus on the legislation’s implementation. We need proper supervision to make sure that the regulatory dialogue works.” – Andreas Schwab (EPP, Germany), Leading MEP on the Digital Markets Act.

In the name of “leveling the playing field” I believe that the DMA does exactly the opposite. The smaller (European) companies will be completely free of the regulation and supervision imposed on the larger (American) companies.

As much as I detest the DMA, my recommendation was that Apple should comply and “tear down the Walled Garden”.

My general impressions of the new DOJ suit

I’ve downloaded and read the DOJ’s complaint. I get the impression that the Biden Administration would very much like to regulate Apple and other large technology companies in much the way that the European Union now does under the Digital Markets Act.

Lina Kahn, the head of the FTC, has more than once espoused similar theories to those that underpin the DMA. The DMA asserts that large technology companies that run platforms such as iPhone, in which users can transact for various goods and services, represent markets that should be subject to regulation.

The complaint comes very close to espousing this theory on page 24:

Smartphones are platforms. Platforms bring together different groups that benefit from each other’s participation on the platform. A food delivery app, for example, is a multisided platform that brings together restaurants ,couriers ,and consumers . A two-sided platform, for example, may bring together service providers on the one hand and consumers on the other. The technology and economics of a smartphone platform are fundamentally different from the technology and economics of a simultaneous transaction platform, such as a credit card, because smartphone platforms compete over device features and pricing in ways that do not directly relate to app store transactions . Whereas credit card transactions reflect a single simultaneous action that requires both sides of the transaction for either side to exist, consumers value smartphone platforms for a variety of reasons separate from their ability to facilitate a simultaneous transaction. Consumers care about non-transactional components of the phone, such as its camera and processing speed, and they care about non-transactional components of apps, such as their features and functionality.

This section argues in much the same way as the DMA for the fundamental difference of the “platform” that requires government regulation but stops short of advocating for that regulation.

It stops short for a very simple reason: there is no legal authority under US law to regulate a “platform” as if it were interstate commerce. I believe a constitutional amendment would be required to implement a DMA in this country.

As I’ve pointed out before, regulating a privately owned store by dictating to the owner the goods and services it can offer, and their pricing, is far beyond the government’s regulatory power authorized by the Constitution.

If there was any doubt about this, the outcome of the Epic Games v. Apple lawsuit laid these to rest. In effect, Epic wanted the government to tell Apple what it could charge for the apps on its App Store, because Epic believed Apple was over charging. Epic wanted the government to tell Apple that it had to carry Epic games, because Apple had banned Epic for non-compliance with developer guidelines.

In both cases, these were the prerogative of Apple, just as any other private store owner has the right to decide what goods to sell and what to charge for them. At least in the US. At least for now.

The lawyers at the DOJ certainly realized this and have resorted to the next best thing, declaring Apple a monopoly that is abusing its monopoly power.

Failing to prove Apple has a smartphone monopoly

The central problem of the government’s complaint is that the assertion that Apple is a monopoly is extraordinarily weak. For most of the complaint, the text simply assumes that Apple is a monopoly without proof. The government doesn’t get around to substantiating the claim of monopoly power until page 66 of the 88 page complaint.

It’s as if, out of self-consciousness of the inadequacy of their monopoly assertion, they wish to bury it where they hope it won’t be noticed:

Apple has monopoly power in the smartphone and performance smartphone markets because it has the power to control prices or exclude competition in each of them. . . In the U.S. market for performance smartphones, where Apple views itself as competing Apple estimates its market share exceeds 70 percent.

What constitutes the performance smartphone market is never defined, at all. But the government acknowledges that Apple’s share of the overall US smartphone market is less than 70%, claiming 65% by revenue.

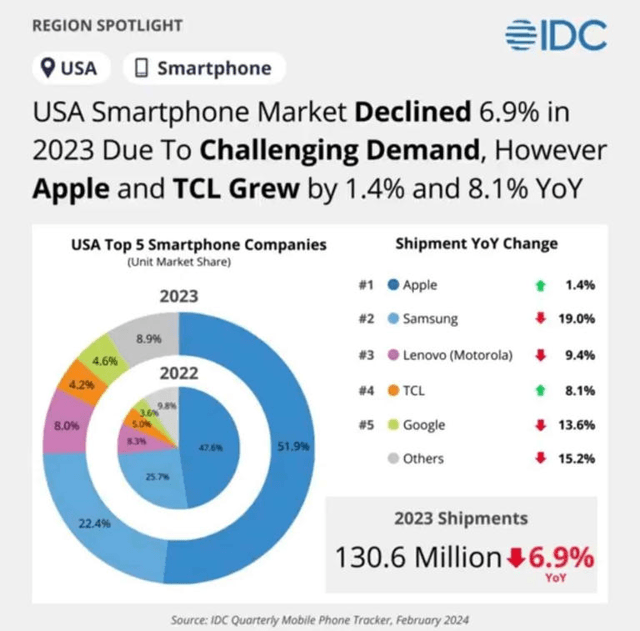

In fact, Apple’s unit market share in the US, according to IDC, was only about 52%:

IDC

The use of the slippery term “performance smartphone” conveys that the DOJ wanted to make it appear that Apple’s dominance of smartphone sales in the US is greater than it actually is. If Apple only made high end iPhone 15 Pro models, the use of the market segmentation might be justified.

But Apple makes lower cost and budget priced iPhones as well, such as the iPhone SE. And it certainly can be argued that the lower priced phones from Lenovo and TCL offer many high end features and compete in the “performance” category, despite their low cost. This is exactly the kind of competition that the complaint claims to want to foster and that Apple has somehow suppressed.

And how Apple might control prices and exclude smartphone competition is never substantiated. All the complaint alleges is that Apple controls the prices charged on its App store, or that Apple controls the prices of its products and services. Well duh.

As a backup to the monopoly claim, the complaint also alleges “Attempted Monopolization” in case the monopoly claim doesn’t fly.

Surprisingly mild remedies

The complaint does go through an extensive laundry list of Apple App Store policies that it claims are anticompetitive. I won’t go through all of them here. I will acknowledge the complaint that some of these policies are designed to make it harder for consumers to switch away from iPhone are valid.

And that does have anticompetitive overtones. Some of the suspect practices:

- Apple clearly favors its own messaging service and makes it hard for competing messaging apps to be competitive on iPhone.

- Apple clearly favors its Apple Pay wallet and virtually makes it impossible for competing wallets to access NFC, rendering them non-viable.

- Apple doesn’t support cross platform smartwatches.

- Apple blocks so called super apps that offer a number of applets within the app. These apps are basically equivalent to web apps. Similar apps would be available within the iPhone Safari browser.

- Apple doesn’t allow game streaming apps on the Store, but game streaming is feasible through the Safari browser. GeForce Now uses the iPhone browser.

In each of these cases, there are good rationales that Apple will undoubtedly provide at trial for their actions. Without fundamental proof of monopoly, it will be very difficult for the government to prove that these are not within Apple’s purview as the owner of its App Store.

But what if the government does prevail in some or all of these purported attempts at monopoly? The requested relief is surprisingly mild:

- Require Apple to accept super apps and cloud streaming apps.

- Require Apple to make available to developers “private APIs” that provide functionality for messaging, smartwatches and digital wallets, thereby enabling third parties to better compete with Apple services and devices associated with iPhone.

- Require Apple to refrain from contractual restrictions on developers and others that would be anticompetitive.

There’s also a catch all “relief as needed to cure any anticompetitive harm”, which probably translates into some form of monetary penalty. But notice what isn’t there. There’s no requirement to accept third party app stores or side loading. There’s no attempt to set prices for Apple.

Investor takeaways: thankfully, we’re not the EU

Fundamentally, under current US law, the government must respect Apple’s property rights. The App Store, and iPhone are Apple’s property, not the government’s. I doubt that any of the requested relief will have a serious impact on Apple’s revenue.

But I doubt that much of the requested relief will be granted. As the owner of its App Store, Apple has the fundamental right to determine what goods and services its store will offer. As the owner of the technology in iPhone, Apple has the right to reserve for its own use any APIs that it has developed.

On the other hand, contractual restrictions in restraint of trade are almost always found to be in violation. Apple will almost certainly lose on this point, but to little harm.

Overall, I see very little financial harm arising from the government’s suit. The apparent investor reaction to the suit is overblown. I remain long Apple and rate it a Buy.

Analyst’s Disclosure: I/we have a beneficial long position in the shares of AAPL either through stock ownership, options, or other derivatives. I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it (other than from Seeking Alpha). I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.

Seeking Alpha’s Disclosure: Past performance is no guarantee of future results. No recommendation or advice is being given as to whether any investment is suitable for a particular investor. Any views or opinions expressed above may not reflect those of Seeking Alpha as a whole. Seeking Alpha is not a licensed securities dealer, broker or US investment adviser or investment bank. Our analysts are third party authors that include both professional investors and individual investors who may not be licensed or certified by any institute or regulatory body.

Rethink Technology offers unique insights into technology trends and companies.