Summary:

- Exxon Mobil has been a reliable dividend player but that doesn’t mean ex-ante the dividend was never at risk.

- The company’s scale and integrated model offer significant diversification compared to upstream players but XOM is still a cyclical business.

- When purchasing XOM stock for income, the entry point will matter a lot more for the long-term total returns compared to a defensive stock.

- The Pioneer acquisition may be positive for the dividend to the extent it diversifies even further XOM’s portfolio and improves cash flow stability through the industry cycles.

Michael M. Santiago

Is Exxon Mobil (NYSE:XOM) a good dividend stock? The oil major made big news last week when it agreed to acquire Pioneer Natural Resources (PXD) in an all-stock transaction valued at $59.5B. This is Exxon’s largest acquisition since the $41 billion XTO deal back in 2010. In 2019, a Raymond James analyst, with the benefit of hindsight, described the XTO purchase as an ill-timed bet on U.S. natural gas:

Exxon’s acquisition of XTO stands out as a textbook example of how not to do M&A. It was an ill-timed bet on U.S. natural gas prices, which have trended down throughout the past decade. As such, it caused long-term pressure on Exxon’s profitability metrics.

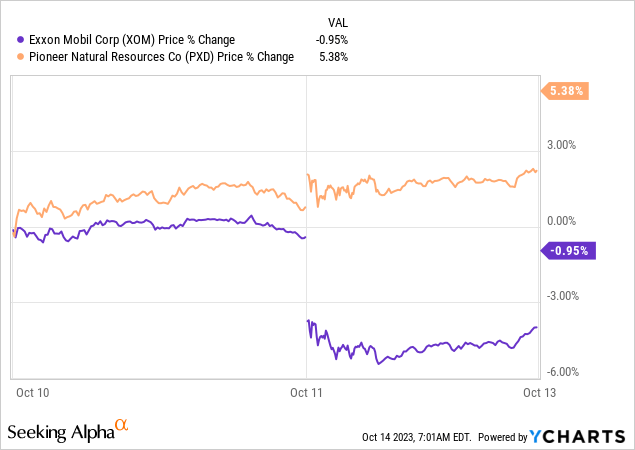

Perhaps due to the XTO overhang, the market didn’t seem to appreciate the PXD announcement:

Moreover, many retail investors look at XOM as a long-term hold and value it for the reliable dividend which wasn’t cut even when WTI oil futures (CL1:COM) went negative in 2020. Does the deal change anything regarding the dividend?

What makes a good dividend stock?

If you have been exposed to academic finance, you may recall the Miller and Modigliani argument that without taxes, transaction costs or asymmetric information about management’s intentions the dividend policy should be irrelevant for stock performance and valuations. The only thing that should really matter is the quality of the company’s future investment opportunities. For example, one of the highest performers over the last few years has been Tesla (TSLA); Elon Musk’s company isn’t known for paying dividends but the market (rightly or wrongly) puts a very high value on its investment opportunities.

The Miller and Modigliani conditions are of course oversimplified. Investors pay taxes and transaction costs; a regular dividend may also reduce the asymmetry of information by constraining management’s ability to invest in negative present value projects. Last but not least, many individual and institutional investors simply need current income. You could theoretically generate income from a non-dividend paying stock by selling shares at regular intervals but that as noted carries its own costs.

In practice, companies that pay greater dividends tend to be more mature businesses with limited reinvestment opportunities. Dividend paying companies also typically come from less cyclical industries such as consumer staples (VDC) or utilities (XLU). You could probably say that a fixed dividend is a signal of management’s confidence in the stability of the business. Buybacks and variable dividends also return capital to the shareholders but management isn’t obliged to maintain them in bad years.

Importantly, a very high dividend – or a dividend that can only be supported at the expense of increasing leverage – doesn’t by itself make for a good dividend stock. If anything, leverage supported dividends may indicate the underlying business is more cyclical than what management wants to project. The dividend may also be at risk of being cut, i.e., the stock may be a “dividend trap.”

Why don’t oil & gas companies pay greater dividends?

At the end of the day, oil & gas is a cyclical industry and producers can’t control the price of their output. For this reason, large U.S. independents like Marathon Oil (MRO), APA Corporation (APA) and Occidental (OXY) have prioritized buybacks while others focus on special or variable dividends.

Exxon and other majors like Chevron (CVX) have more generous fixed dividends because their sheer size and integration across the oil and gas value chain provide for greater diversification that dampens cyclicality:

- Majors like XOM have a downstream (refining) unit that to some extent provides a natural hedge for the upstream production; for example, if crude oil prices fall, but refining throughput is limited, as has been the case recently, Exxon can offset falling upstream profits by earning higher refining margins.

- Exxon also has a petrochemicals business that is less correlated to the transportation demand for fuels.

- The majors are also quite involved in the LNG (liquefied natural gas) supply chain which provides another source of diversification. Natural gas delivered via LNG powers industry but also meets residential heating and electricity demand which is less cyclical.

That said, integrated energy may be safer than standalone upstream plays, but it’s still riskier than defensive sectors like consumer staples.

So is XOM a buy-and-forget dividend stock?

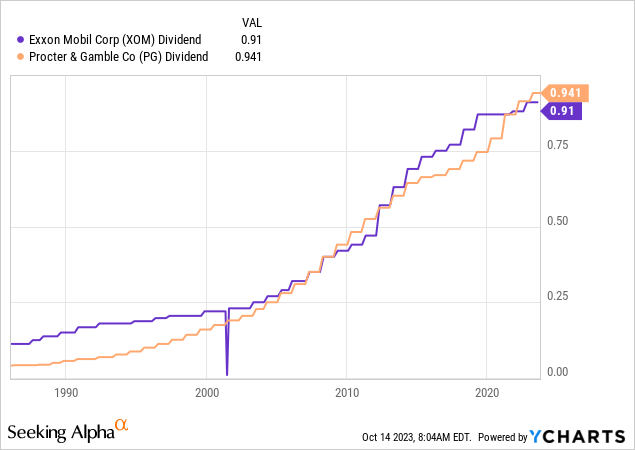

It depends on your time horizon. Exxon has steadily grown its dividend for now 40 years; this is on par with a defensive stock such as Procter & Gamble (PG):

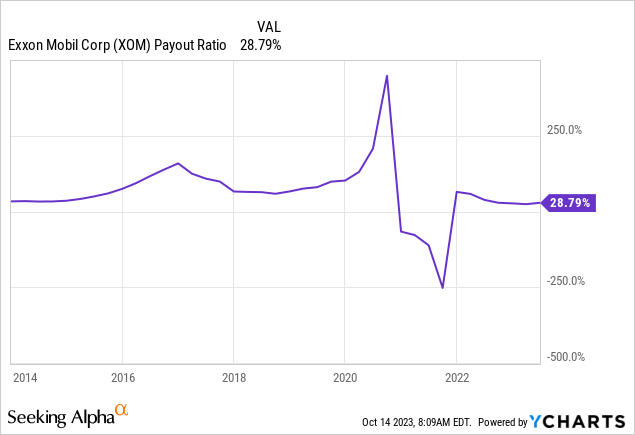

However, a nice realized dividend growth series doesn’t mean the dividend was safe all along the way:

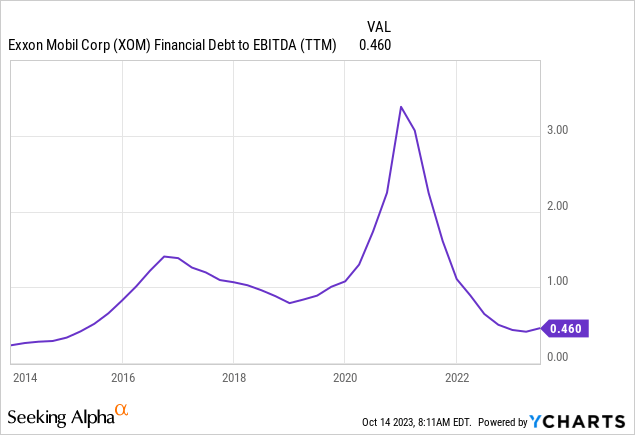

Over the last 10 years the payout ratio has varied from -250% to +250%. The financial leverage also tends to yo-yo a bit:

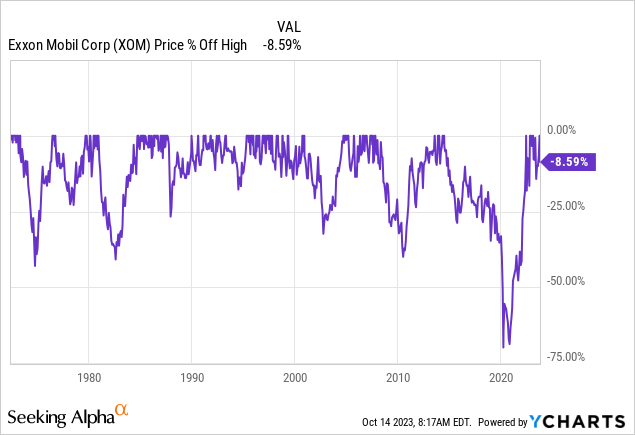

Unsurprisingly, the dividend coverage and leverage are inversely related to the stock price drawdowns which have exceeded 25%:

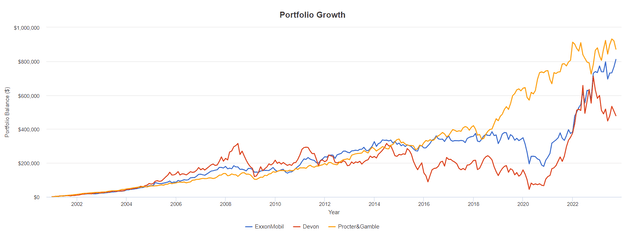

Should you care about drawdowns if you’re a buy-and-hold investor though? I would say yes. Even if you never sell any stocks, you still have to decide when to buy more and most people make repeated contributions to their portfolio over time rather than invest a lump sum once and forever. To illustrate this point, I ran a backtest that assumes you started with $1,000 in January 2001 and invested another $1,000 each month thereafter, all the way through September 2023. I compared Exxon to PG, as a typical consumer staples company, and to Devon (DVN), as a more risky, upstream player. I assumed all dividends were reinvested:

Ultimately, XOM and PG got you to a similar place but arguably PG did so with fewer sleepless nights. A XOM-only portfolio was more stable than Devon but still lacking compared to a pure defensive stock.

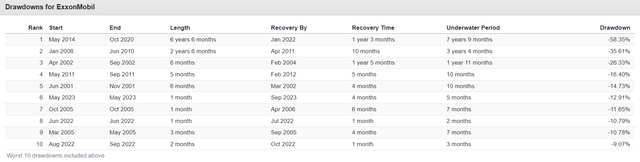

Here are also the XOM drawdowns/underwater periods:

In 20 or so years, there were 3 drawdowns of 25% or greater with underwater periods of 2, 3 and almost 8 years! In contrast, PG had only one drawdown of 25% or more that continued for three and half years.

So does this mean XOM is bad dividend stock? No. However, it shows that it should be managed actively.

Does the dividend inform the valuation?

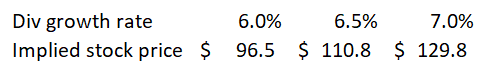

To some extent yes. The “dividend discount model” or DDM is one of the basic valuation tools that can be applied to a dividend paying company. Exxon grew its dividend from $0.23 per quarter to $0.91 over the last 22 years. This implies a CAGR (compound annual growth rate) of about 6.5%. Assuming 10% cost of equity, XOM may be close to its intrinsic value; however, note the sensitivity to minor changes in the growth assumption:

Author’s calculations

We have been trading in a $100-$120 range for over a year now, so the DDM approach isn’t very useful.

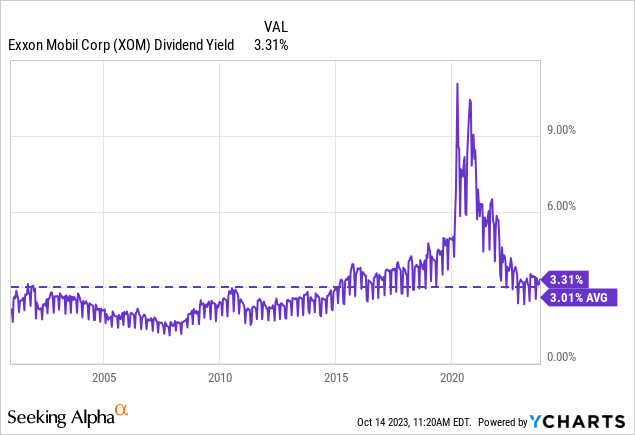

A simpler approach is to look directly at the dividend yield:

Historically, for Exxon it has averaged about 3%. At the $110 or so stock price now, XOM yields 3.31%. For the yield to converge to its historical average, the stock price would need to appreciate to $120. The caveat is that a 3% yield in a 5% risk-free rate environment isn’t the same as a 3% yield when the risk-free rate is close to 0%.

Exxon’s oil-price adjusted ROCE is at its highest in 15 years

The problem with the DDM is that Exxon is a capital intensive business. A dividend paying consumer staples or utility company can focus on maintenance capex with predictable returns. This is why we can base our valuation considerations on the dividend. Exxon certainly has maintenance capex too but oil fields get depleted and new ones need to be discovered and developed. The success of Exxon’s business is more sensitive to its capital allocation decisions, whether they are poor, as XTO, or good, as many consider Guyana to have been.

Exxon’s ROCE (return on capital employed) may therefore be more informative as I have discussed in a different article:

Prior to 2008, Exxon achieved higher ROCE compared to the 2009-2021 period when adjusting for the oil price. It looks that 2022-2023 may have broken away from the “lean” period and are more consistent with the profitable years before 2008. This is why I am bullish long-term on the stock.

So is XOM a buy, hold or sell?

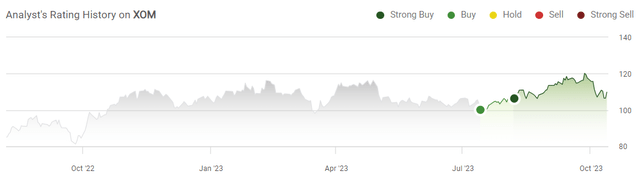

Tactically, XOM’s stock is a bit in no man’s land right now. We’ve been stuck in a $100-$120 range for over a year. I would be more comfortable recommending a buy if we were closer to $100 or moving back up after hitting $100:

Secondly, in the last few days we have seen another geopolitical conflict unfold, this time in the Middle East and oil went up on the risk premium. However, most geopolitical events start with a spike in oil prices early in the crisis (e.g., 1991 Gulf War, Russia-Ukraine last year) after which the impact fades. Barring an escalation involving more actors that may bring us to WW3 (XOM stock won’t be my primary concern if that happens!), I would expect oil to give up some gains. This may affect XOM’s stock price too although it may also not given equities have not fully participated in the latest oil rally.

In summary, I do think $140 is possible but I don’t have a view if we are going to see $100 or $120 first. Personally, I am long XOM but trimmed 25% of my position at $120 when we failed to break above that level for the third time in a row this year.

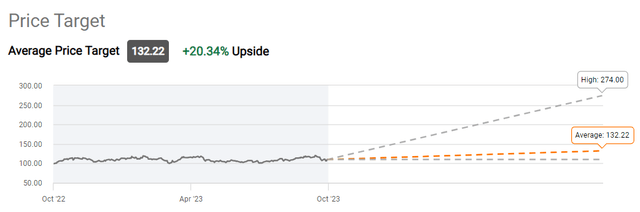

Wall Street’s average target is $132, which makes sense, but note the dispersion around the average:

The $274 by the way seems to be a data feed error. It is the target an analyst gives to Pioneer based on a XOM target of $118 and the exchange ratio agreed in the all-stock deal. Nevertheless, the range of forecasts is indeed broad.

Does the Pioneer acquisition change anything?

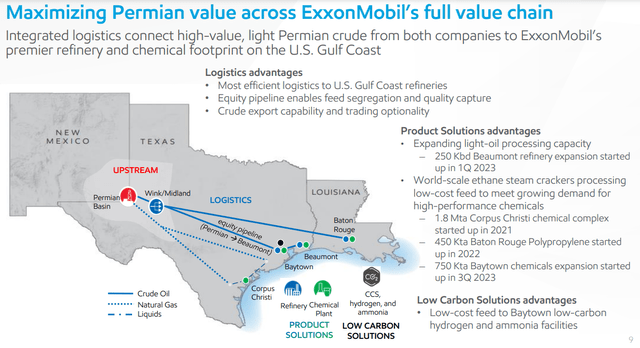

The short answer is no. The XTO deal didn’t derail the upward trajectory in Exxon’s dividend and I don’t expect the PXD one to do so either. If you seriously consider opening an Exxon position, I encourage you to check out the entire acquisition presentation, but here I will focus on just one slide that shows some of the strategic rationale for the deal:

While Pioneer is known to be one of the U.S. independents with longest shale inventory runway (perhaps 15-20 years), the deal isn’t just about the upstream aspect. Pioneer will also be integrated into Exxon’s downstream infrastructure which should reduce further the volatility of the combined company’s cash flows. So, if something does change, I think it will be greater diversification/cash flow stability which is helpful from a dividend perspective – to the extent of course things can ever be “stable” in energy.

Bottom line

XOM has been a reliable dividend player but that doesn’t mean the dividend was always safe. Investors need to differentiate between ex ante and realized risk. Just because we lucked out doesn’t mean things couldn’t have gone badly. Currently, XOM’s business is improving structurally (higher returns on capital, adjusted for the oil price) so that bodes well for the dividend too.

However, while Exxon is much safer as an investment than a pure upstream oil and gas player, it isn’t a buy and forget stock. Despite the diversification that comes with the integrated model, energy remains a volatile sector. Even if you never sell stocks, deciding when to buy XOM will be more consequential for your long-term returns compared to the impact of the entry point on an investment in a traditional defensive stock.

Analyst’s Disclosure: I/we have a beneficial long position in the shares of XOM either through stock ownership, options, or other derivatives. I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it (other than from Seeking Alpha). I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.

My articles, blog posts, and comments on this platform do not constitute investment recommendations, but rather express my personal opinions and are for informational purposes only. I am not a registered investment advisor and none of my writings should be considered as investment advice. While I do my best to ensure I present correct factual information, I cannot guarantee that my articles or posts are error-free. You should perform your own due diligence before acting upon any information contained therein.

Seeking Alpha’s Disclosure: Past performance is no guarantee of future results. No recommendation or advice is being given as to whether any investment is suitable for a particular investor. Any views or opinions expressed above may not reflect those of Seeking Alpha as a whole. Seeking Alpha is not a licensed securities dealer, broker or US investment adviser or investment bank. Our analysts are third party authors that include both professional investors and individual investors who may not be licensed or certified by any institute or regulatory body.