Summary:

- The EU antitrust charges are actually only the last salvo fired against the very same target around the world: Google’s ad-tech business.

- This article explains what regulators are complaining about and what is at stake for Google.

- Given the increased valuation and high level of uncertainty, I now rate Google only as a Hold.

Google’s moat might have become more fragile recently.

PM Images/iStock via Getty Images

What Are The EU’s Antritrust Charges Against Google?

What appeared in major news headlines as a “break-up threat” from the European Commission to Google parent Alphabet (NASDAQ:GOOG) (NASDAQ:GOOGL) – for example here – was actually only the last of several hits against the same target, i.e. Google’s ad exchange business. It came on the heels of a similar antitrust probe in the UK (one year ago) and several similar proceedings in the very U.S. (for example in January).

Google itself downplayed the issue as usual. In particular, it stated that the claims are “not new and relate to a narrow part of our advertising business” and obviously accused the Commission of a not understanding “how advanced advertising technology helps merchants reach customers and grow their businesses — while lowering costs and expanding choices for consumers.”

The latter part is an easy game for Google. Effectively, the inner workings of the digital advertising market are terribly complicated and probably only few readers of the general public understand what Google may be accused of.

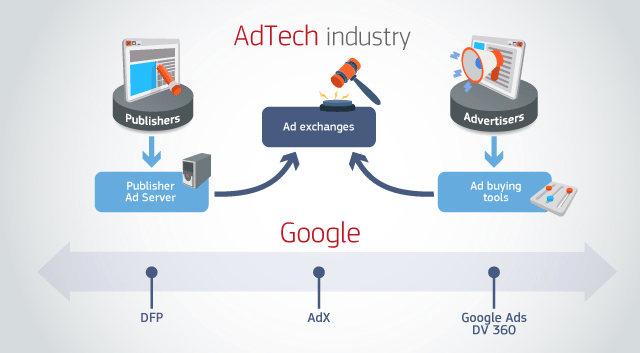

The graphic included in the Commission’s statement doesn’t really help either:

The ad-tech business as seen by the EU Commission. (EU Commission statement)

Yet, things are actually quite simple: If you want to sell a stock for at least $8, you contact your broker and provide the minimum bid you would accept. On the other side of the trade, the prospective buyer of the stock does the same with another broker and communicates the highest acceptable price of $8. Both brokers forward those bids to the stock exchange. If the buy and sell orders match, the trade is executed for $8: You get the money you wanted and the buyer gets the stock for an acceptable price. Both brokers get their commissions and so does the stock exchange.

Now imagine that both brokers and the exchange belong to the same business. — What could happen in the advertising world?

For example, the ad space seller (e.g. an online newspaper) could receive the notice that there is no higher bid for the ad than $5, although the highest real bid is effectively $8. Nobody could verify this claim, since all information remains inside the broker/exchange business. Hence, the ad space seller might finally settle for a lower price and sell the ad space for $5. But the exchange would still get $8 from the buyer and pocket the difference.

— You believe this is too far-fetched? — Think again. I have simply described what Google has allegedly already done: According to the complaint filed in Texas, internally the scheme was called “Project Bernanke” and “Quantitative easing”, as it effectively created an additional pool of money that was later used to prop up bids that were too low and therefore were lost to competing ad exchange platforms. Thanks to the price boost, the business remained on Google’s platform and, hence, damaged its competitors.

While “Project Bernanke” might not have led to additional income for Google itself, it certainly damaged the ad space sellers (who got less than what they should have received) and/or the buyers (who paid more than what they should have paid) and also Google’s competitors. Using its clients’ money, Google would have siphoned business away from its peers.

It is not our business today to establish what was effectively done and whether it was evil or not. However, the case illustrates what’s the issue here: Google’s dominant position can easily lead to anti-competitive conduct, even if it is not for the company’s own direct financial benefit.

Over time, any ad exchange might naturally become a monopoly (or close), just as stock exchanges. This is simply because nobody wants to check hundreds of small exchanges for bid and ask prices before transacting. — But there is no natural need for the buy or the sell side broker to outright own the exchange. The exchange monopoly works perfectly well when it remains separate from the broker’s business and the temptation to run some “quantitative easing” can thus be avoided.

What Should Investors Be Aware Of?

When Alphabet states that the complaint concerns only a “narrow part of our advertising business” it achieves two things:

- Investors might believe there is not much to worry about, as even it was forced to sell the ad exchange, the damage would be small.

- It looks like the Commission is nitpicking and blowing things out of proportion.

In my opinion, both assumptions are wrong. But Google has excellent reasons for downplaying the issue (which is apparently big enough to cause antitrust interventions in many major jurisdictions all over the globe).

Sure, experts believe the ad-tech business accounts for about 12% of Google’s overall revenues and not the entire 12% comes from the contested ad exchange. Yet, the “Project Bernanke” scheme highlights that this is not only about revenues and money.

It is about competition.

As I have highlighted in my most recent articles about Google, the company’s monopoly is under constant threat and probably perceived by management itself as a lot more fragile than most investors believe.

If a competitor managed to build the necessary scale, much of Google’s advertising revenue might actually evaporate. While the ad exchange is certainly not the only building block of Google’s moat, it still is important. If the ad exchange was run by a different company, ad prices might fall (because the different company might be content with a commission below Google’s 20% take rate or because it would not be able to do any “quantitative easing”). And lower advertising prices would impact Google quite heavily.

In addition, losing control over its ad exchange might lead to the emergence of a strong competitor in the space.

This is probably what was behind the alleged “preferential” treatment for Facebook (META):

Facebook, the complaint says, agreed to “curtail its header bidding initiatives” and send the millions of advertisers in its Facebook Audience Network to bid on Google’s platform. In return, Google would give the Facebook Audience Network special advantages in ad auctions, including setting aside a quota of ad placements to Facebook, even when the company didn’t make the highest bid. The agreement, the complaint says, “fixes prices and allocates markets between Google and Facebook.”

How May Google Be Impacted by EU Antitrust Charges Going Forward?

Even before the latest news from Europe, antitrust expert Matt Stoller had put it in quite drastic terms:

[Google] is now facing so many antitrust claims that it has to win them all to maintain its existing business model. If Google loses this case, then that’s not only billions of dollars that will flow back to our newspapers and publishers, but it’s a precedent for breaking up a dominant tech firm. If Google wins, well, it has to win four other cases against the government, as well as anything else filed by private litigants. Increasingly, that’s a tall order.

While Matt Stoller clearly has his own agenda, investors should be aware of the increasing fragility affecting Google’s moat.

When the largest antitrust institutions of the Western hemisphere zero in on one single aspect of Google’s business, it definitely should be a major concern.

My personal opinion is that it certainly has been the United States’ interest to let Google build an international monopoly (or close to). Being able to basically control the flow of advertising money all around the globe has evident political benefits, as this money is what ultimately maintains publications, who in turn feed the journalists which form the public opinion, exert public control over governments etc.

However, this does not mean it is in the United States best interest to maintain such a monopoly forever. Especially, if there are U.S.-based alternatives.

Therefore I would not be surprised if, over time, Google might get some serious competition from other U.S. tech giants, such as Microsoft (MSFT) in search and Amazon (AMZN), Meta or Apple (AAPL) in advertising.

Google Stock Key Metrics

Since I first (timidly) issued a Buy rating for the stock, Google has performed very well, returning 31%. It now trades close to the top of its 52-week range for 23 times forward earnings.

For what it’s worth, sell-side analysts predict earnings to be back at 2021 levels in 2024 and grow 14% from there. So the stock is trading for just under 17 times expected 2025 earnings.

This is obviously much less attractive than back in February, when I already considered that the years of compound 18% revenue growth are probably over for the digital advertising market. In addition, the caveats exposed above apply: In a more competitive ad market, prices might fall.

Moreover, the AI revolution might lead to additional revenues, but also to higher costs.

What Is The Future Outlook For Google Stock?

I keep my cautious stance on the stock, as explained in my last article: The trajectory of profit growth has become much more difficult to project – and capital allocation remains a huge issue.

Bottom Line: Downgrading To Hold

Considering the increased, much less attractive market valuation of the company, I consider Google to be only a Hold right now. While I see the many growth opportunities, very important risks have emerged and are increasingly likely to materialize. Since I am not alone in observing this situation, this is probably what is weighing on the stock and will likely continue to keep its valuation from rising to previously reached ultra-bullish levels.

Analyst’s Disclosure: I/we have no stock, option or similar derivative position in any of the companies mentioned, and no plans to initiate any such positions within the next 72 hours. I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it (other than from Seeking Alpha). I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.

Seeking Alpha’s Disclosure: Past performance is no guarantee of future results. No recommendation or advice is being given as to whether any investment is suitable for a particular investor. Any views or opinions expressed above may not reflect those of Seeking Alpha as a whole. Seeking Alpha is not a licensed securities dealer, broker or US investment adviser or investment bank. Our analysts are third party authors that include both professional investors and individual investors who may not be licensed or certified by any institute or regulatory body.