Summary:

- Judge Amit Mehta ruled that Google maintains its monopoly in search and search text advertising through restrictive contracts, violating the Sherman Antitrust Act.

- Remedies will likely include abolishing restrictive contracts, impacting Google’s revenue and benefiting competitors like Apple and Microsoft in the long term.

- Google’s ability to escalate CPC pricing will be restricted, potentially affecting its long-term growth prospects.

- Despite regulatory challenges, Alphabet remains a Hold due to its strong management and innovation capabilities, though future growth is uncertain.

Boy Wirat

On Aug. 5, 2024, Judge Amit Mehta released his decision in U.S. v. Google LLC, a suit brought by the U.S. Department of Justice and 11 States under the Sherman Antitrust Act. The judge found that Alphabet Inc. (NASDAQ:GOOG) (NASDAQ:GOOGL) is a monopoly in the areas of general search engines (GSE) and in the critical monetization vehicle of search text advertising, the text ads that appear at the top of a search results page. Having easily established that Google has monopoly power, the decision asserts that Google unlawfully maintains that power via various restrictive contracts with companies that offer Google search as part of their products. These companies include Apple Inc. (AAPL), Mozilla, various Android device OEMs, and various U.S. cellular carriers. Among the various remedies available, the abolition of such contracts will certainly be mandated. Cessation of such contracts will have far-reaching consequences for parent company Alphabet as well as the companies with which Google contracted.

Google, the Internet search monopolist

Mehta points out that being a monopoly per se is not a violation of Sherman. A company may attain monopoly status legitimately through superior competition and legal protections such as patents and copyrights. However, if a company uses its monopoly power to restrict or prevent competition, that’s a violation of Sherman.

The typical means by which monopolists illegally restrict competition is through contracts with customers that preclude the customer from engaging in business with a competitor. Such contracts are illegal under Sherman, even when they stop short of an outright ban on business with a competitor.

But the first step in an antitrust case is to establish the monopoly power of the defendant, in this case, Google. The government’s case is mostly based on Google’s huge market share, as stated in the decision:

Plaintiffs easily have demonstrated that Google possesses a dominant market share. Measured by query volume, Google enjoys an 89.2% share of the market for general search services, which increases to 94.9% on mobile devices. This overwhelms Bing’s share of 5.5% on all queries and 1.3% on mobile, as well as Yahoo’s and DDG’s shares, which are under 3% regardless of device type. Google does not contest these figures.

DDG is DuckDuckGo, a provider of browsers that claims to offer superior privacy, including search.

The decision also points to the very high barriers to entry into the general search market. These include enormous capital costs as well as development costs to create a competitive search engine. These barriers are so high that even large companies such as Apple have been discouraged from entering the search market. Furthermore, there’s effectively zero venture capital interest in funding a competing search engine.

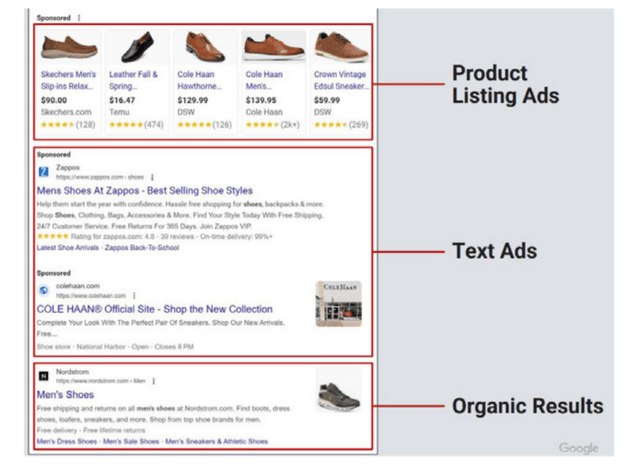

The decision also concludes that Google has monopoly power in another key area, which is search text advertising. Such text ads appear at the top of a search results page and are tailored to the interests of the user who initiated the search. According to the decision, Google had an 88% share of text ads as of 2020.

Example search advertising. (US v. Google decision)

How search and advertising work and how Google employs its advertising pricing power

One of the most interesting aspects of decisions such as Mehta’s is that it provides insights into the companies involved that would not otherwise be available. This includes financial information as well as technical information.

In defending themselves in antitrust suits, companies are often forced to divulge information about their inner workings and decision-making that would normally never see the light of day. Such information is usually not flattering. Google is no exception, although what may be unique about Google is its lack of self-consciousness about its actions.

The crucial first step for a GSE is to “crawl the web,” in which a search provider constructs a massive database of internet websites and their content. Search engines then search the database in response to user queries, usually by matching keywords in the query to the database.

GSEs also apply extensive knowledge of the user making the query. Google literally stores years of user data, including web browsing history, prior searches, Google-mediated purchases, etc. Knowledge of the user helps improve the relevance of the search results and the probability that the search will yield what the user is looking for.

How does a GSE keep track of a user? There are various ways. For instance, a user may simply be logged into their Google account through the Chrome Browser, YouTube, or Gmail. Cookies may be employed, and Google Analytics also provides user tracking, according to a DDG blog:

Google Analytics – a free Google service used by millions of websites and apps – is actually the biggest cross-site tracker on the Internet, lurking creepily behind the scenes on around 72.6% of the top 75k sites. While “analytics” sounds harmless and is in fact something websites need to improve their services, what’s happening underneath the hood with Google Analytics is anything but harmless or necessary.

Unlike privacy-focused analytics services, Google uses their Google Analytics tracker for more than just providing information about site visitors and app users to the sites and apps themselves. In many cases Google also adds that same information to Google’s own massive profiles about people. Since Google Analytics is embedded in so many sites, this tracker alone allows Google to see most people’s global browsing history, regardless of whether they use any Google products themselves.

User tracking, by whatever means, has been essential for the success of Google’s search advertising business. Google is widely regarded as having the most successful monetization of search results. This in itself poses a significant barrier to entry for a GSE provider who attempts to emulate the Google business model.

The process by which ads are served with search results is a remarkable example of a business process unique to the digital age: The search ad auction. The auction takes place in a fraction of a second and is completed before the search results page is displayed. Each unique search query is accompanied by a unique digital auction that determines what ads will be displayed at the top of the search results page.

The candidate advertisers for any particular auction are chosen based on loose matching of keywords preselected by the advertiser to keywords identified in the query. But other factors may be considered, such as whether the user has visited sites of the advertiser, has a general interest in the advertiser’s products, etc.

As the term implies, the auction is usually won by the advertiser whose preselected maximum cost per click (CPC) is the highest. Advertisers only pay for clicks on the ad, at the auction-determined CPC. The winning advertiser’s ad appears at the top of the results page, accompanied by the runner-up.

The advertiser’s bid is not the only determiner of who will win. Google has a mechanism for mathematically grading the “quality” of the ad as a function of a predicted “click-through rate.” Higher “quality” ads are more likely to win auctions.

Google also engages in what it calls “Squashing” in which it artificially raises the quality score of the runner-up in an auction, improving the chances that the runner-up will win. Google’s rationale for squashing is that it prevents particular advertisers from dominating auctions. But it also creates artificial pricing pressure by making runners-up more competitive, thereby increasing Google’s ad revenue.

Squashing was just one of many pricing strategies that Google has devised over the years to raise ad prices. Usually, this was done incrementally so that advertisers wouldn’t balk at the price increases. This was assisted by the limited insight Google offers advertisers into the auction process. Generally, advertisers are only afforded broad statistics on ads while the auction mechanism remains a black box.

The decision concludes:

Google’s records make clear that growing its revenue was a principal goal in launching these price tunings. See, e.g., (Google will use its launch “to recover lost revenue from launches which create value for our users and advertisers, but reduce revenue for Google”) . . . (“This work has resulted in products which add several billions of dollars in incremental revenue annually.”) In fact, Google used ad launches to meet revenue goals or make up for perceived deficits in its ad revenue growth. As Dr. Adam Juda, Google’s Vice President of Project Management, testified, a positive 20% increase in revenue “was an annual objective that we would try to get to over the course of an entire year.” And Google met that objective year after year.

In raising ad prices, Google had no concern about competitive pricing, only the near-term reactions advertisers might have. In the long run, advertisers continued to pay the costs as they had no effective alternative.

In his conclusions of law section Mehta states that Google has monopoly power in search text ads partly on the basis of its ~90% market share in these ads, and also due to Google’s pricing strategy:

It is sufficient at this point to observe what is undisputed, which is that Google does not consider competitors’ pricing when it sets text ads prices. That is “something a firm without a monopoly would have been unable to do.”

How Google impacts competition in search via the Apple Internet Services Agreement and other agreements

Having established that Google is a monopoly in the key areas of internet search and in search text advertising, Mehta moves to the next step of showing that Google illegally uses its monopoly power to impair or prevent competition.

A simple and obvious way to do this is for a monopolist to force customers to sign exclusive contracts. The contracts explicitly prevent the customers from buying goods or services from the monopolist’s erstwhile competitors. Because of the monopolist’s power, customers generally feel obliged to sign the contracts. Typically, the monopolist makes the exclusive contracts mandatory in order for the customer to do business with the monopolist. This is termed “exclusive dealing.”

Over the years, the concept of exclusive dealing has been broadened considerably, but still consistent with the wording of Sherman, which bans “contracts in restraint of trade.” In analyzing the contracts that Google employed, Mehta relies heavily on the precedent set by U.S. v. Microsoft.

In general, it’s not necessary for the contract to absolutely prohibit dealing with a monopolist’s competitor. And Google was careful not to include such prohibitions in its contracts. Rather, a contract is illegal under Sherman if it serves to “foreclose” or block entry by a competitor to a significant percentage of a given market, usually 40% or more.

Mehta examines these contracts in detail in Section VI of the decision, “The Relevant Contracts.” Generally, the contracts restrict competitive access to the GSE market, and effectively, to the search text ad market as well.

How the contracts do this is exemplified by the Google-Apple Internet Service Agreement:

The Internet Services Agreement (ISA) is an agreement between Google and Apple, wherein Google pays Apple a share of its search ads revenue in exchange for Apple preloading Google as the exclusive, out-of-the-box default GSE on its mobile and desktop browser, Safari.

Because most users never bother to change the default, the agreement effectively forecloses competitors from a substantial share of the searches performed on Apple’s platforms. 65% of all search queries are entered through the default access point in Safari. Google receives nearly 95% of all GSE queries on iPhone.

Users can change the Safari default, and the ISA doesn’t prevent Apple from offering users alternatives to the Google default. Google may have felt that these looser restrictions would allow it to escape liability under Sherman, and indeed it argued so.

Google was able to achieve a huge share of Apple Safari searches on all devices that offer Safari, including iPhone, iPad, and Mac. According to the decision, 28% of all searches in the U.S. originate in the Safari default.

Google paid handsomely for the privilege of being the default. The contract stipulated that Apple would receive a (redacted in the decision) percentage of Google’s ad revenue from Safari and Chrome browser searches on Apple devices. In 2022, this was estimated to be $20 billion. Google’s payment to Apple was larger than all of its similar revenue-sharing/default placement contracts with other vendors.

The decision details how Apple has tried to find alternatives to Google, but to no avail. This is probably the most indicative of the anticompetitive effect of the ISA. Apple explored developing its own search engine. In 2018, it hired the head of Google Search, John Giannandrea, to be Chief of Machine Learning and AI Strategy.

Apple developed some elements of the GSE, such as web crawling, but stopped short of a full GSE. But the cost of losing the Google ad revenue was too great. Giannandrea wrote in an email:

. . . there is considerable risk that (Apple) could end up with an unprofitable search engine that (is) also not better for users.

Microsoft also sought to supplant Google as the default search engine with Bing. Microsoft approached Apple in 2015 and offered to provide a much higher percentage of ad revenue than Google, about 90%. Apple analyzed the Microsoft offer, assuming 100% of ad revenue, and even then, found that Microsoft couldn’t compete with Google on remuneration.

Apple was also very concerned about offering customers an inferior GSE. As Eddie Cue, head of Apple Internet Services, testified:

. . . there was “no price that Microsoft could ever offer (Apple)” to make the switch, because of Bing’s inferior quality and the associated business risk of making a change. “I don’t believe there’s a price in the world that Microsoft could offer us. They offered to give us Bing for free. They could give us the whole company.”

The decision examines a number of other agreements that worked along the same lines as the Apple ISA. These include agreements with Mozilla, Android OEMs, and US cellular carriers that configure and sell Android devices. These were referred to as Revenue Sharing Agreements (RSAs).

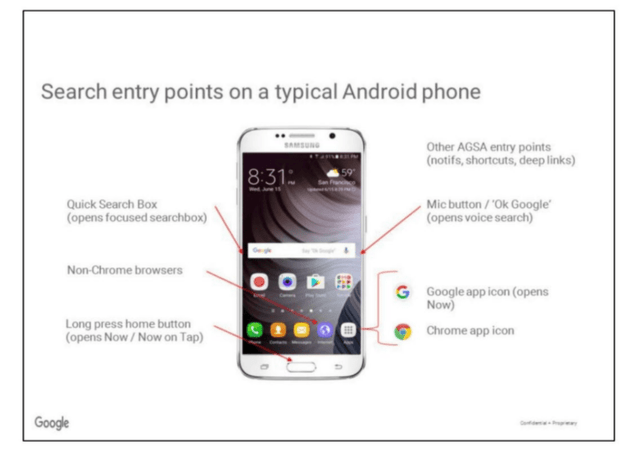

The RSAs require that the Google search widget be prominently displayed on the Android Home screen as the default for the device:

Android default home page. (US v. Google decision.)

Although the RSAs don’t explicitly forbid preloading of competing search engines or browsers, Android device makers and carriers generally do not load such applications. The reason is concern about degrading the user experience with “bloatware,” a variety of apps that the user might consider useless. There were no Android devices sold in the U.S. that were not covered by an RSA.

The RSAs have been very effective in preserving Google’s dominant position in mobile search. In the Conclusions of Law section, the decision states that Google enjoys an 89.2% share of the overall search market, which increases to 94.9% for searches from mobile devices.

During the trial, Google presented various arguments as to why its RSAs were not illegal. First Google claimed that it wasn’t a search monopoly by virtue of other search engines and query vehicles, such as social media platforms. These arguments were generally not accepted, given the definition of the GSE and search text advertising markets.

Google also offered various arguments as to why the RSAs themselves were not illegal. Google claimed, naturally, that they didn’t explicitly preclude users from loading or selecting as default other search engines. Such arguments were also properly rejected.

The decision simply concludes:

For the foregoing reasons, the court concludes that Google has violated Section 2 of the Sherman Act by maintaining its monopoly in two product markets in the United States-general search services and general text advertising-through its exclusive distribution agreements.

Likely remedies and their impacts

Mehta did not discuss remedies or corrective actions in the decision. These will be decided in a future proceeding. On Sept. 6, a status conference was held concerning remedies. The DOJ was given until December to propose remedies, with a final decision on remedies put off until August 2025.

The Verge has a good article on the types of remedies that are being discussed by Google’s rivals. And the CEO of Yelp, Jeremy Stoppelman wrote in a blog post:

While we’re heartened by the decision, a strong remedy is critical. As we’ve previously suggested, any remedy must both address Google’s past misconduct and protect against future misconduct. Google should be required to compete based on the merits of its products and must be prohibited from continuing its exclusionary practices, such as exclusive default search deals and self-preferencing its own content in search results. During the trial, Google argued that vertical search providers, like Yelp, are rivals to Google Search, yet it has consistently used its monopoly to unfairly advantage its own search verticals at the expense of Yelp and others.

Additionally, to ensure a level playing field, Google must spin off services that have unfairly benefited from its search monopoly, a straightforward and enforceable remedy to prevent future anticompetitive behavior. As former Special Assistant to the President for Technology and Competition Policy Tim Wu highlighted in The New York Times last fall, breakups have long been an effective tool to combat anticompetitive misconduct and foster innovation.

At a minimum, the abolition of the RSAs can be expected. Some companies, such as Apple and Mozilla, will lose substantial revenue. However, I don’t expect the court to be sympathetic toward companies that benefited monetarily from Google’s illegal practices.

While a possible breakup of Google is appealing to its rivals, I’m not convinced that it will be implemented. The problem here is that it will be difficult to show that a breakup along reasonable organizational lines will be effective in reducing Google’s dominance in search and search text advertising.

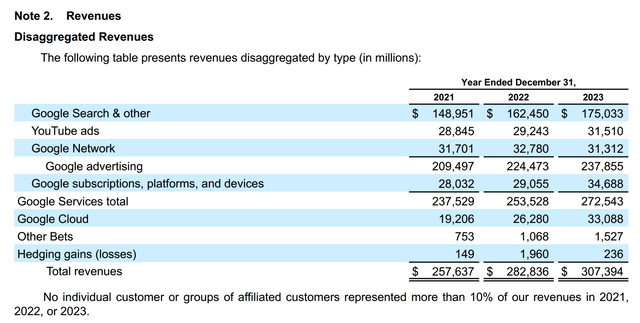

As Google’s financial reports make clear, search advertising is the revenue fount on which Google’s other businesses all depend:

Source: Alphabet 2023 SEC 10K.

For instance, if Android were spun off, how would the ecosystem support itself? Currently, Android is free to OEMs, as are the key Android mobile apps like the Play store. Would Android be able to pay for itself in the future by licensing?

The government would likely be very concerned about weakening competition in smartphones, given the suit against Apple alleging its smartphone monopoly in the U.S.

Looking further ahead, how would Android compete with other AI-enabled platforms provided by Microsoft and Apple? Such a remedy would effectively diminish Android’s dominance, but that isn’t the subject of the suit or decision.

The fundamental problem here is that separating the search business from other Alphabet businesses simply leaves the search business free of the financial burden of supporting the other Alphabet businesses. The search would be free to apply its enormous revenue to maintain its dominance.

Any spin-off scenario one can concoct ends up in the same predicament. While search user tracking is enabled within Chrome, it doesn’t require Chrome, since tracking can be done through any browser that supports cookies. Also, Google Analytics probably provides most of the user tracking that Google needs.

Whatever benefit there might be from spinoffs can be achieved by the abolition of the RSAs. I believe that Google will argue successfully that a spin-off of Android would damage Android irreparably and harm consumers.

A spin-off of Chrome may be harder to forestall, but here, the argument against comes down to the question, “what’s the point?” It doesn’t really diminish the revenue generating power of Search. Wherever Search goes in a breakup scenario, the ad revenue follows, leaving Search in a dominant position.

The sole benefit of spinning off Chrome would be to eliminate Google search as the default in Chrome. But once again, this can be done through a behavioral remedy.

I believe that rather than a breakup, which arguably harms consumers, the court will mainly focus on behavioral remedies, such as the abolition of RSAs. There will likely also be restrictions on auction pricing, since this was clearly abusive. And the proposal that Google not prefer its own services in search results will also likely be adopted.

The most impactful remedy, financially, is the abolition of RSAs, so let’s look at that. The cost of the RSAs, including Apple, is reported as Traffic Acquisition Costs – TAC. In fiscal 2023, TAC was $50.866 billion, according to Alphabet’s 2023 annual report, or 29% of search advertising revenue.

Abolition of the RSAs would actually save Google about $50 billion per year in costs. Instead of default placement in browsers and the Android home screen, users would need to select from a menu of options at the initial setup of the device or browser.

Google would likely lose some search share in this process, but would it lose roughly 30%? That’s a hard question to answer, but I think that it would not, at least at the beginning when competitors are still relatively weak.

Over time, competitors may gain market share. And Apple, deprived of the incentive to do nothing, may pursue development of its own search engine. Also, in the context of future AI enabled operating systems, search and generative AI are inextricably linked. Apple would likely pursue search as part of its broader AI strategy.

So, in the short term, I doubt that Google is harmed financially by the lack of RSAs. It loses some percentage of search revenue but makes up for it by recovery of the TAC expense. In the near term, I think Google comes out ahead, although the top line will see a year-over-year decline.

Investor takeaways

In some analysis that I’ve read, it has been assumed that any remedies would have to await the outcome of Google’s appeals, which could take years. This is not a foregone conclusion.

In U.S. v. Microsoft, the remedy of breaking up Microsoft was stayed on appeal and ultimately overturned. But this was considered draconian, and the judge in the case was removed out of ethics concerns. On the other hand, in the U.S. v. Apple e-book case, remedies were applied all during Apple’s lengthy, and ultimately fruitless appeals.

Judge Mehta seems determined not to repeat the mistakes of the judge in the Microsoft case. He’s taking a very careful and measured approach to the remedies phase. I believe he will ultimately conclude that behavioral remedies along the lines I’ve outlined will be appropriate.

As such, I expect that the remedies will be in force even as Google works through the appeals process. The immediate impact will be to restrict Google’s ability to grow revenue through its contrived CPC pricing, as well as saving Traffic Acquisition Costs.

Over time the remedies can be expected to erode Google’s search and search advertising market share. The likely outcome of the remedies is to create a tripartite world in which Google, Microsoft, and Apple compete in search, AI assistants, and computing operating systems and platforms.

I see that future as ultimately benefiting U.S. consumers and is the outcome the government will attempt to craft. However, it does call into question Google’s long-term growth prospects.

When I first wrote this article for my investing group, I declared Alphabet a Sell, but I want to soften that a bit. Alphabet is a very intelligently managed company under CEO Sundar Pichai, and capable of tremendous innovation, as shown at its recent Google I/O and Made by Google events.

I wouldn’t sell short Google’s ability to compete effectively in the coming tripartite world. But the easy growth through CPC escalation is going away. I’m sure of that.

While I’m not willing to be a buyer of Google, given the vast uncertainties, I can see where current shareholders would be willing to ride out the regulatory storm. Therefore, I rate Alphabet a Hold.

Analyst’s Disclosure: I/we have a beneficial long position in the shares of AAPL either through stock ownership, options, or other derivatives. I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it (other than from Seeking Alpha). I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.

Seeking Alpha’s Disclosure: Past performance is no guarantee of future results. No recommendation or advice is being given as to whether any investment is suitable for a particular investor. Any views or opinions expressed above may not reflect those of Seeking Alpha as a whole. Seeking Alpha is not a licensed securities dealer, broker or US investment adviser or investment bank. Our analysts are third party authors that include both professional investors and individual investors who may not be licensed or certified by any institute or regulatory body.

Consider joining Rethink Technology for in depth coverage of technology companies such as Apple.