Summary:

- Halliburton is one of the largest oil service companies in the world, providing services and equipment for oil and gas exploration and production.

- The company’s largest competitors in the oil services market are SLB Inc. and Baker Hughes.

- Halliburton derives a larger share of its revenues from North America compared to its competitors, giving it more leverage to the production of oil and gas from shale fields in the US and Canada.

- Long-term evolution in the shale business and industry M&A benefits Halliburton, but the company faces shorter-term headwinds.

- I’m rating the stock a Hold for now but believe it could see upside to the high $40s into early 2025.

lyash01

When I start analyzing a company, I always ask myself a series of questions.

Two of the most important are:

Which companies are in the peer group?

What makes this company different or unique from its peers?

It’s useful to understand a company’s peers for several reasons including to assess how the market values companies in a particular industry and what are considered normal earnings or cash flow multiples. In addition, it’s often possible to track trends across multiple companies in the same, or related, industry groups providing useful information for assessing relative growth prospects.

The second question is crucial to understanding the relative performance of different stocks in the same industry group.

Halliburton Company (NYSE:HAL) is one of the largest diversified oil service companies in the world. HAL is not a producer – the company doesn’t produce and sell oil or gas – rather, it provides crucial services and equipment needed to explore for and produce hydrocarbons.

Put in a different way, when a company like Exxon Mobil Corporation (XOM) or EOG Resources, Inc. (EOG) spends money – capital spending (CAPEX) – on drilling new wells or developing new oil and gas projects, much of that spending represents revenues for the oil services companies.

In HAL’s case, its largest peers – competitors in the oil services market – are Schlumberger Limited (SLB), the company formerly known as Schlumberger, and Baker Hughes Company (BKR). The biggest differentiating factor between HAL and its two largest competitors is that HAL derives a much larger share of its revenues from North America.

Per Bloomberg, HAL derived 45.6% of its 2023 revenues in North America compared to around 20% for SLB and 26% for BKR. That’s crucial in the oil services business because it means HAL has far more leverage in the production of oil and gas from shale fields in the US and Canada than its large-cap peers. Indeed, within North America, HAL’s main competitors are much smaller firms such as ProFrac Holding Corp. (ACDC).

In this article, I’ll explain why the shale business is in the midst of a historic transformation that’s related to the recent wave of mergers & acquisitions (M&A) activity we’ve seen among producers in the region. I’ll also outline why I believe HAL has a significant competitive advantage over smaller oil service rivals in the region and how that could ultimately drive the stock higher towards my 12-month price target in the upper $40s, a more than 20% premium to the current quote.

Finally, while HAL has significant long-term advantages, I’m rating the stock a “Hold” for now because it faces two near-term headwinds that look likely to limit appreciation potential through the middle of this year.

Let’s start with this:

Shale: From Growth to Profitability

It’s useful to divide the global oil services industry into two pieces by geography: North America and International.

The former is dominated by shale drilling and completion activity:

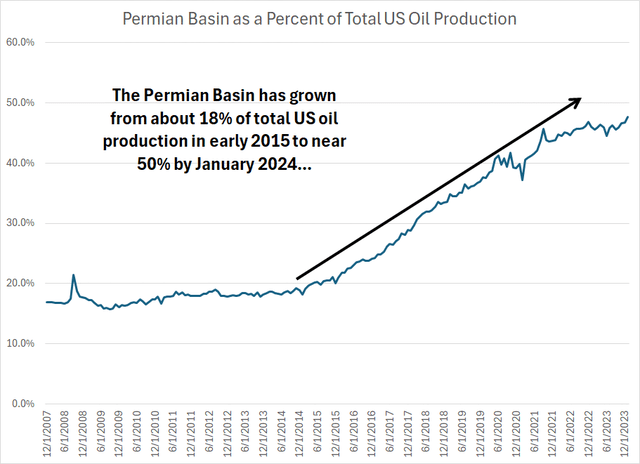

Permian Basin as a Share of Total US Oil Production (Energy Information Administration (EIA))

According to the Energy Information Administration (EIA) Drilling Productivity Report, oil production from the Permian Basin alone was roughly 5.98 million bbl/day in January 2024, around 48% of total US oil production. That’s up from just over 18% of oil production in January 2015, less than a decade ago.

And, if we sum up expected oil output in April 2024 from the three largest oil-producing shale regions of the US – the Permian of Texas and New Mexico, the Bakken of North Dakota, and the Eagle Ford in south Texas — the total comes to around 8.6 million bbl/day, a commanding two-thirds share of total US oil output.

A decade ago, in April 2014 the EIA estimated the same three shale regions produced just under 3.9 million bbl/day, around 46% of total US oil output at that time.

Shale is more like a manufacturing business, or an industrial process, than conventional oil and gas exploration and development. That’s because producing more oil or gas from shale is largely a matter of ramping up drilling and completion activity. The term drilling is self-explanatory; for shale producers, completion refers to fracturing a well and putting it into production.

So, from the dawn of the shale boom in the late 2000s up until roughly 2020, shale producers generally chased commodity prices:

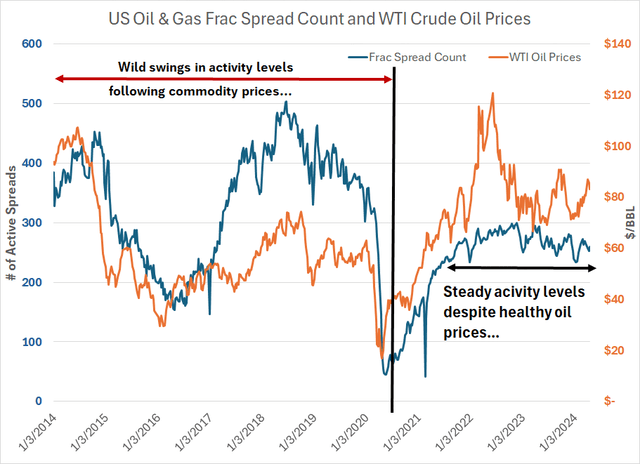

Frac Spreads and Oil Prices (Bloomberg)

Fracturing, often called “pressure pumping” in the industry, is the magic sauce for producing shale.

Oil doesn’t exist naturally underground in some sort of giant lake, nor is natural gas found in an underground cavern. Instead, the hydrocarbons are found trapped in the pores, natural cracks, and fissures of underground rock formations. In a conventional reservoir, those pores and cracks are well-connected (the field has good permeability), so oil and gas can flow naturally into the well powered by geologic pressures.

In shale, however, that’s not the case. So, producers must provide that permeability artificially by pumping fluid (mainly a water-sand mix) into a well under tremendous pressure to physically break up the rock, creating artificial fractures/cracks through the shale. That’s known as hydraulic fracturing.

The sand, known as proppant, is designed to flow into those fractures to keep them open as the pressure is reduced following the fracturing process.

A shale well can’t be produced economically without fracturing. While there are hydrocarbons trapped in the shale, there’s no way for them to flow through the reservoir rock naturally into the well in economic quantities.

A frac spread is simply a collection of pump trucks, crews, and related equipment needed to perform the hydraulic fracturing process.

My chart above shows the total US frac spread count from Bloomberg since early 2014 (blue line) as well as the closing price of front-month West Texas Intermediate (WTIC) oil futures (orange line).

The correlation between these two series prior to roughly 2020-21 is clear. For example, at the beginning of my chart, through the first nine months of 2014, oil prices were elevated at around $100/bbl and so was fracturing activity with over 400 active frac spreads at times that year. Simply put, with oil around $100/bbl, US shale producers were actively drilling and completing wells to bring more production online and take advantage of high commodity prices.

Oil prices then began a long slide from late 2014 through early 2016; producers responded by slashing their drilling and fracturing activity and the frac count collapsed to under 150 active spreads by early 2016.

Then, from 2016 through much of 2018, oil prices rallied, and the pattern repeated — US shale producers responded by drilling and fracturing more wells with the frac spread count jumping over 500 in 2018.

In short, through the 2014-18 period, the US shale industry was a story of booms and busts mirroring swings in commodity prices.

What’s crucial is this pattern started to change in 2020-21. While the fracturing spread count did recover as WTI rallied from its spring 2020 COVID-19 lockdown lows, the frac spread count hit a wall in the 250 to 300 ranges by late 2021. Even as oil prices soared in 2022 to well over $100/bbl, US shale producers roughly maintained their activity levels on this basis.

Indeed, the average weekly price of oil since the end of 2022 is about $78/bbl, a comfortable level for most oil-focused shale producers, however, the US frac spread count has drifted slightly lower over this time, a trend visible on my chart.

As the shale industry matures, producers have become far more disciplined.

Here on Seeking Alpha, I’ve covered a long list of shale oil and natural gas producers in recent months including, most recently, Matador Resources Company (MTDR) in “Profitable Oil Growth, Raising Target,” EOG Resources in “Organic Growth at a Discount” and Devon Energy Corporation (DVN) in “Turnaround Underway, Time to Buy.”

While these producers operate in different shale basins and have various commodity production mixes, they all share one common overarching strategy – most shale producers are focused on generating positive free cash flow even with moderate crude oil prices. Most are also promising to return significant capital to shareholders as dividends, via share buybacks, or through paying down debt (transferring value from creditors to shareholders).

Over the past three months, the majority of producers I cover have issued guidance for 2024 production and, in most cases, I’ve covered here on Seeking Alpha, US shale producers are spending just enough to roughly maintain their production through 2024 adjusted for any recent acquisitions.

Long story short, we’re not seeing a dramatic surge in drilling and completion activity this year despite generally rising oil prices because producers aren’t targeting barrels of production, they’re targeting profitability and cash flow.

Pressure Pumping and Halliburton

HAL is one of the largest providers of fracturing services in North America through its Completion and Production business segment, which accounted for some 59% of revenues last year.

So, as you might expect, the historic volatility and commodity sensitivity of the shale business I just outlined translates into significant volatility in HAL’s North American operations:

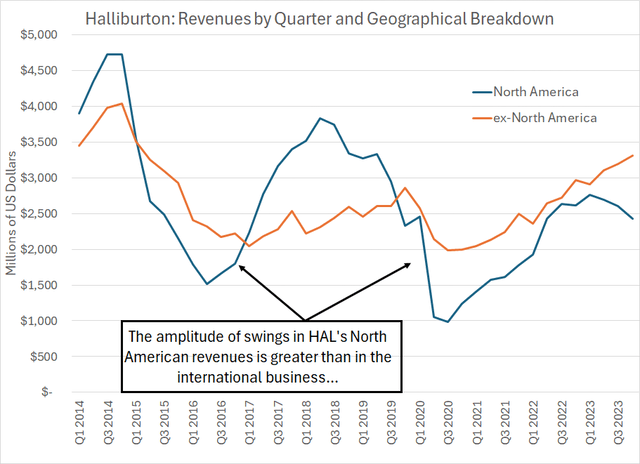

HAL Revenues Segmented by Geography (Bloomberg)

This chart shows Halliburton’s revenues by quarter since Q1 2014 broken down into North American sales (blue line) and international revenues (excluding North America) pictured as an orange line.

Two points to note.

First, the amplitude of swings in HAL’s North American revenues is significantly greater than for its international revenues. That’s a direct result of the boom-and-bust pattern evident in shale oil and gas drilling and fracturing activity I just outlined.

For example, just look at the shale bust of late 2014 to early 2016 when HAL’s North American revenues collapsed from around $4.75 billion per quarter to about $1.5 billion per quarter over the course of just around 18 months. Then, there was a boom from 2016 through mid-to-late 2018 followed by an even bigger bust into the commodity price collapse of early 2020 amid COVID-19 lockdowns.

Of course, when commodity prices fall sharply, as they did in 2014-16 and 2018-2020, exploration and drilling activity tends to fall globally. However, international revenues are historically far more stable for HAL than North America.

That’s primarily because conventional oil and gas developments outside North America often take the form of long-term projects targeting fields that take years to find, develop, and bring into production.

A classic example would be Exxon Mobil’s world-class find in Guyana; XOM announced its first discovery there in May 2015 and has subsequently unveiled more than 30 additional discoveries on the same offshore Stabroek Block. The company produced its first commercial oil from Guyana in late 2019 and has continued to develop the project in stages; as of Q4 2023, the company was producing 440,000 barrels of oil equivalent per day from the country and is targeting over one million by the end of 2027.

Simply put, Exxon Mobil is unlikely to dramatically alter its plans for developing the Stabroek Block due to short-term fluctuations in commodity prices. And the company typically signs long-term contracts with multiple services firms like HAL and SLB, to perform work related to developing a project like the Stabroek Block. That leads to more stable, predictable revenues over time.

The second point to note is HAL’s North American revenues have been coming down since early last year while its international sales have continued to trend higher, growing about 11.6% year-over-year in Q4 2023 compared to a 7.2% decline in North America revenues year-over-year.

Naturally, the obvious fear here is that HAL’s North American business could be entering another one of those dreaded bust cycles when a decline in shale drilling and fracturing activity leads to a slump in revenues and profits.

Fears of a big downturn in North America also explains, at least in part, why Halliburton underperformed SLB, its closest diversified oil services peer, from April 2022 through the summer of 2023:

Take a look:

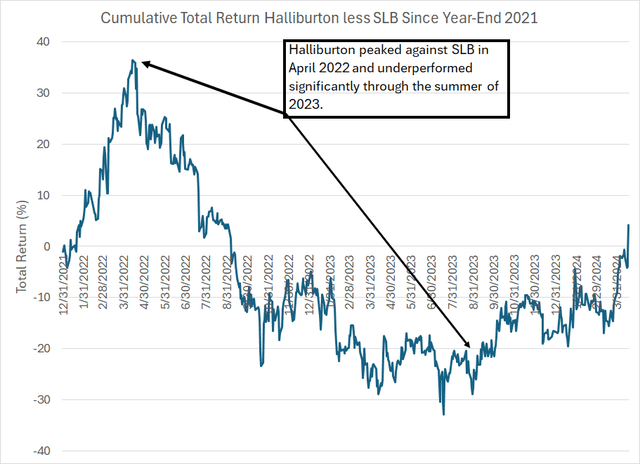

Relative Stock Performance HAL to SLB (Bloomberg)

To create this chart, I calculated the cumulative total return from both HAL and SLB since the end of 2021. The line shows HAL’s cumulative total return less SLB’s total return on a dividends-reinvested basis; when this line is rising, HAL is outperforming and vice versa.

When commodity prices soared in early 2022, HAL initially outperformed, likely on the view that shale drilling and production activity would accelerate to offset supply disruptions caused by the Ukraine-Russia conflict. However, that outperformance reversed in dramatic fashion from roughly mid-April 2022 through the summer and early autumn of 2023.

If you scroll back and look at my chart of the US fracturing spread count, you’ll see it peaked in late 2022 and, in my chart of HAL’s revenues, you can see North American revenues peaked in Q1 2023. Over the same time, international revenues continued a clear pattern of growth; in fact, HAL’s international revenues have reached the highest quarterly levels since late 2014, the top of the last big upcycle, over the past two quarters.

Given SLB’s greater exposure to international oilfield spending and HAL’s significant leverage to the more volatile North American business, it’s clear investors showed a preference for SLB from April 2022 through last summer.

That trend has since reversed – something I’ll explain in just a moment – however, the key point to note is that HAL’s stock tends to see significant leverage to expectations for North American fracturing activity. And North American revenues and activity levels have a reputation for commodity sensitivity and volatility grounded in the experience of the shale boom and bust years.

In my view, many investors underappreciate two major changes in North America – one industry-wide and the second specific to HAL – that are changing this pattern of boom and bust.

Let’s start with this:

Changing Customers

Historically, there are three major categories of customers for oil services firms outside the US – the large integrated “supermajors,” national oil companies (NOCs), and a handful of large independents.

As I mentioned earlier, international oil and gas projects tend to be large-scale, multi-year developments targeting major conventional (not shale) reservoirs. Developing these projects requires billions in up-front capital investment often years before the first drop of commercial oil. As I mentioned earlier, XOM announced its first Guyana discovery in May 2015 and didn’t produce commercial oil and gas for sale – or start generating significant revenues – until almost five years later in December 2019.

My point is the big supermajor integrated producers like XOM have historically been the only companies large enough, with enough technical expertise, and with a low cost of capital low enough, to develop a project like Guyana. It’s a matter of scale – this year XOM has a CAPEX budget of $23 to $25 billion, which is almost as much as the entire market capitalization of Devon Energy at $33 billion with the latter considered a large-cap shale producer.

NOCs are typically fully or partly owned by the local government and have varying degrees of technical expertise and financial strength. For example, Saudi Aramco, majority-owned by the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, is a technically sophisticated NOC that routinely works with oil services companies like SLB and HAL. Others, like Algeria’s NOC, Sonatrach, tend to partner with US and European oil majors on new projects; these NOC-integrated joint ventures also contract with major services firms on projects.

There are also a handful of large US independents with significant international projects including Occidental Petroleum and EOG Resources. Since international projects tend to be large-scale in nature, they’re typically operated only by the largest independents.

Generally, international spending on oil and gas development is longer-term and strategic in nature; companies tend to make investment decisions based on a low long-term breakeven cost. In the case of XOM, the company has indicated that 90% of its developments worldwide, including Guyana, can generate a greater than 10% annual return on investment even with Brent Crude Oil at $35/bbl compared to a closing price of $87.29/bbl on Friday, April 19 per Bloomberg.

The shale industry is different.

As I illustrated earlier, shale producers have tended to be more responsive to commodity prices over time, accelerating activity when oil and gas prices rise and cutting CAPEX and activity when prices fall.

One reason is it takes far less time for a group of shale wells to be drilled and put into production than a vast international project – weeks rather than years – and upfront costs are much lower. For much of the industry’s history, shale production has been dominated by smaller independent exploration and production firms (E&Ps) and private operators.

That’s changing, and the shale industry is increasingly dominated by the same firms, and types of producers, as international oil and gas spending.

Some of that shift is due to the wave of merger and acquisition (M&A) activity underway.

I’ve already spilled some ink on XOM’s big international project in Guyana in this article. However, the company is also a massive producer in the Permian Basin in the US — last October, for example, XOM agreed to buy Permian producer Pioneer Natural Resources Company (PXD) in an all-stock deal worth close to $65 billion including assumed debt.

At the time the deal was announced, XOM controlled some 570,000 net acres in the Permian and Pioneer controlled more than 850,000 acres. Combined this massive position produces more than 1.3 million barrels of oil equivalent per day and Exxon has targeted growth to 2 million boe/day by the end of 2027 pending closing its deal to buy PXD.

And, in December, large independent E&P Occidental Resources agreed to acquire privately held CrownRock in a $12 billion deal adding some 170,000 boe/day of production to OXY’s existing position. OXY now expects to produce 569,000 to 599,000 BOE/day from its Permian position alone including CrownRock.

Another large Permian independent, Diamondback Energy, Inc. (FANG), announced a deal to acquire privately held Endeavor Energy Resources for $26 billion in February of this year, boosting its position in the Permian to 838,000 net acres and 816,000 boe/day of production. The company believes it has 6,100 drilling locations – years of inventory – that’s profitable at prices below $40/bbl WTI.

As these integrated producers and large independents scale up their US shale businesses and the industry consolidates, the strategy has started to morph into one that closely resembles the traditional international project model.

In XOM’s case, the company has three main strategic growth areas outlined in its latest Corporate Strategic Plan – Guyana, Permian, and Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG). The company’s Permian Basin assets compete with other projects in its portfolio; just as with conventional international projects like Guyana, the company’s plan is to ramp up Permian output to a sustainable plateau (2 million boe/day with Pioneer by 2027) and to generate free cash flow from the asset at prices around $35 per barrel or higher.

For the oil services providers that operate in North American shale, there’s good news and bad news.

On the positive side, the focus on low breakeven costs and steady, large-scale development should help alleviate the boom-and-bust cycles that have plagued the shale industry from its infancy two decades ago. You can already see that to an extent in the charts of fracturing spreads I outlined earlier – the industry hasn’t shifted activity as dramatically to swings in commodity prices since 2021 as they did back in the 2014-2020 era.

On the negative side, these large-scale shale producers are far more efficient than the traditional smaller and private operators – they can produce more oil and gas with fewer drilling rigs and using less fracturing capacity.

Take a look:

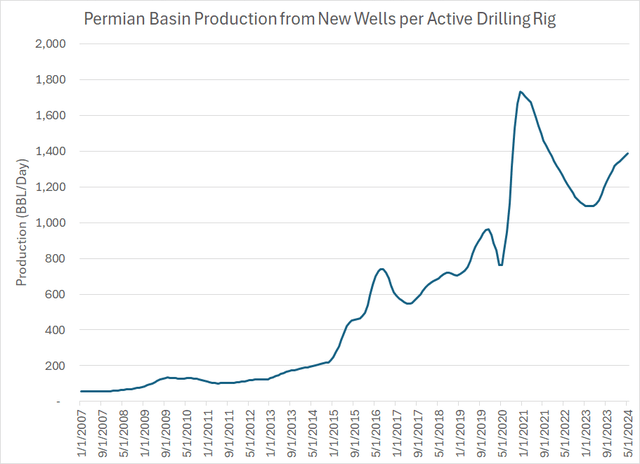

Permian New Well Production per Rig (Energy Information Administration)

This chart shows the total oil produced from new wells per drilling rig in the Permian Basin region since 2007. As EIA acknowledges in the notes to the report this productivity metric can become unstable during periods when the number of rigs operating in the play rises or falls dramatically (such as the spring 2020 commodity collapse). However, the long-term trend here is clear – Permian producers are producing more oil with fewer active rigs.

Greater efficiency and productivity is good news for the producers – it means more oil and lower costs per barrel – however, think about it in terms of the oil services firms like HAL. If producers don’t need as many rigs or fracturing spreads to grow their oil or natural gas production, that means less work for the services firms.

Simply put, while the “busts” aren’t likely to be as dramatic as the industry experienced in the 2014-2020 era, the industry is capable of growing production without as much raw fracturing capacity or as many rigs, so there’s less work for the North American service providers, and drilling contractors, in aggregate.

Put in a different way, some of the value of the US energy industry has shifted from the services firms to the producers as a result of these efficiency gains.

I believe this plays right into the hands of larger players like HAL, which brings me to this:

ZEUS and e-Frac

The simple fact is that a large integrated oil company like XOM demands a high standard of operating efficiency from the service companies it works with and will likely favor large, well-capitalized providers like HAL over smaller operators. It also likely helps XOM have experience with HAL providing key services for its international projects.

Much the same can be said of a large independent producer like Diamondback Energy.

These large-scale shale producers are likely to prioritize quality of service, efficiency, and equipment up-time over raw costs when it comes to executing on steady, multi-year shale drilling plans.

HAL is increasingly differentiating its North American services business through the introduction of its ZEUS electric fracturing (e-frac) completion solution. Historically, fracturing spreads have largely been powered by diesel, which is expensive. Moreover, while diesel engines are a time-tested, reliable technology, the high-capacity engines that power fracturing pumps do wear out over time and require significant maintenance to operate at peak efficiency.

In the summer of 2021, Halliburton announced deployment of the ZEUS system as part of a multi-year contract with Chesapeake Energy Corporation (CHK) in the Marcellus Shale region of Appalachia. In that project power is generated on-site by partner, VoltaGrid, which has generators capable of using natural gas, LNG, and a variety of other fuels. In this case, Chesapeake can use field natural gas produced locally from its existing operations.

Halliburton has deployed a similar system for FANG in the Permian, using power generated from a central power generation facility built by VoltaGrid. Back on FANG’s Q4 2022 call in early 2023, this exchange during the Q&A portion of the call highlighted some positive efficiency gains from the ZEUS system:

Analyst Question: Yes, good morning. I want to circle back on the completion efficiency comments, e-frac — e-frac obviously brings a pretty good fuel savings given that the gas diesel spread here and obviously associate the ESG benefits. But do you think e-frac additions will be additive to the improvement in cycle times above and beyond what you’re seeing from simul-frac?

FANG CEO Travis Stice: Yeah, I think generally Scott, they complete a similar amount of lateral feet as the simul-frac crews, as we’re seeing early time. But on top of that e-fleets, on a fuel efficiency basis, not just the type of fuel but the efficiency of the fuel used is — has been a positive surprise.

I think the last thing I would add is that it does, it does operate on a much smaller footprint. So, maybe your moves are smaller, but you do have some electrical infrastructure associated with those, those fleets. Dan, do you want to add anything to that?

FANG COO Daniel Wesson: Yeah, I think we’ve only been running the first crew for about six months and we’ve been really impressed with the performance thus far. It has outperformed our other fleets kind of on the margin, but not too measurable. We do believe that over time, you’ll see that gap widen in performance just really believe that the maintenance required around the e-fleet equipment will be substantially less. So, we’re excited to learn through that with Halliburton and recognize some added efficiencies in proper just fuel savings as we go forward.

Source: Diamondback Energy Q4 2022 Earnings Call

This quote is from a little over a year ago, the early days of the FANG deal with Halliburton. However, the company was already highlighting both substantial fuel savings from using electricity generated using FANG’s field natural gas as well as lower maintenance costs and downtime for the e-frac equipment relative to diesel fracturing spreads.

From Halliburton’s perspective, however, the most important point of all is that producers like Chesapeake and Diamondback are willing to sign long-term contracts to cover its ZEUS fracturing services.

During HAL’s Q4 2023 earnings call three months ago in late January, the company announced that 40% of their entire fracturing fleet in 2024 represents ZEUS e-frac fleets and that “well over half” will be electric in 2025. As the company builds and deploys new e-frac fleets, it’s retiring older diesel-powered spreads. HAL also noted these e-fleets are “on multiyear contracts, generating a full return of and return on capital during their initial contract terms.”

A little later in the same call, HAL’s CEO described the process of contracting the ZEUS e-frac fleet as a negotiation between the producer and HAL focused on long-term value to be extracted from the system.

Here’s what HAL CEO Jeff Miller had to say during the Q4 Call in response to an analyst question:

Look, e-fleets are accretive. They’re accretive for a couple of reasons. Number one, highly efficient to operate from our standpoint. And so that makes them more accretive. Clearly, they are bringing a lot of value to clients, and therefore they’re priced and thought about differently in the marketplace. And so, look, I expect that, that will continue into the future.

But I think what’s most important is the contracted nature of the fleets, which means a couple of things also. Number one, that the pricing is sticky, but it’s sticky because it’s contracted over time and the value is thought about. And so, sophisticated procurers can look at that and model that and we can model it as well and be comfortable with the value created.

But I think the second thing as we think about what types of customers look at e-fleets, these are not — these aren’t a spot market solution. I mean, the companies that are interested in e-fleets are those that have steady programs, work through cycles, have a clear vision of where their business needs to go and are willing to commit to the technology to deliver that over the long term. And so — and really, it’s an entire system.

Source: HAL Q4 2023 Earnings Call Transcript

Two main points to note.

First, historically contracting for fracturing work has been based on short-term contracts or the “spot” market – a producer contracts for a certain number of wells to be completed at a certain time, paying a market rate based on the supply and demand for spreads. So, it was largely a commoditized market.

The e-frac solution is different – HAL isn’t competing with older diesel fleets in the spot market, it’s negotiating multi-year deals with producers at fixed prices, and it doesn’t build new ZEUS fleets until they’re backed by long-term contracts.

Second, note HAL’s comments about the customer base, along the lines I outlined earlier. The companies that are willing to contract with HAL to use ZEUS are large producers with a steady development program in a shale field like the Permian, not operators who will dramatically shift their CAPEX plan based on near-term commodity price trends.

Bottom line: The shale business is changing, evolving, and consolidating and HAL looks well-placed to benefit thanks to its differentiated technologies like ZEUS that appeal to larger, more efficient shale producers. Over time, I’d expect this to translate into more consistent revenues and profit margins for HAL in North America compared to the volatile shale boom and bust era prior to 2021.

Shale Short-Termism

After years of short, high-amplitude shale cycles, investors are (understandably) wary of the North American oil services cycle and the potential for the recent slide in drilling and completion activity to provoke a swoon in HAL’s business.

There are some clear signs of a big, positive shift in the North American cycle in the HAL’s business. A little earlier on in this article, I posted a chart of HAL’s North American revenues, which have only seen a modest slide despite the retrenchment in drilling and completion activity since 2022.

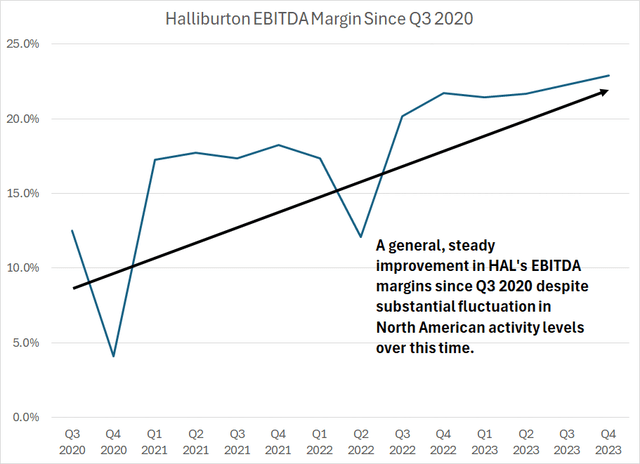

You can also see it in HAL’s profit margins:

HAL EBITDA Margin since Q3 2020 (Bloomberg)

Despite substantial volatility in shale drilling activity since late 2020, HAL’s overall profit margins on an EBITDA basis have steadily improved over this time.

Regardless, the market remains worried about the profitability, and the potential for a downturn, in HAL’s North American operations. Investors are easily spooked by any evidence that pricing power is fading in North America due to lower activity.

Consider these comments from the Q4 2023 conference call of a fracturing competitor in North America, ProFrac:

Analyst Question: Good morning, gentlemen. I wanted to see if you could give us a sense of the tuck-in pricing concessions. Did you yield, call it, relative to the leading edge in order to improve utilization from the beginning of the fourth quarter?

And thoughts on could this — what has been maybe the reaction to — from your peers, from some of your market share gains? Do you worry that this could have maybe a destabilizing impact on the level of pricing discipline that we did observe in the industry last year.

ProFrac Chairman Matthew Wilks:

Good morning, Arun. I really don’t care what it does to our competitors. I don’t spend a lot of time thinking about them. We’re doing what’s right for ProFrac. We’re taking market share. We’re not going to hold up pricing to their benefit and feed market share to do it. We’re taking our market share back and don’t really care what it does to them. What I like is what it does for us.

Source: ProFrac Q4 2023 Earnings Results and Conference Call March 13, 2024

Simply put, in 2023 overall drilling and completions activity in US shale fell as I outlined earlier. However, most competitors in the business remained disciplined on price; in ACDC’s case, management believes they were too aggressive in maintaining prices in 2023, ceding market share to key competitors.

So, as you can see referenced in the above quote, the company has decided to get more aggressive on pricing concessions this year in an effort to regain market share and improve the utilization of its frac fleet. Utilization, a measure of activity relative to fleet capacity, is important because idle days for fracturing equipment spell less revenue and, potentially, higher costs to maintain or reactivate idle equipment.

An analyst asked ACDC if they thought lowering prices would lead to a sort of “price war” with its competitors, a list that would include HAL, as its peers seek to maintain their own market share by also offering concessions.

Chairman Matt Wilks responded by saying he doesn’t care what this strategy does to competitors and that ACDC is intent on taking market share.

That’s clearly not the sort of comment that instills confidence in the profitability of the shale services business – the read-through for HAL is that there’s a risk they might have to cut pricing for North American services to maintain market share, leading to another “bust” cycle.

As I’ve outlined, my view is that these fears are overblown – HAL clearly offers a differentiated, higher-tech product in ZEUS than ACDC, a company that still contracts significant equipment on the spot market or under short-term contracts. In a sense, it’s two very different markets, and HAL’s position insulates it from any pricing concessions on lower-end equipment.

Regardless, it’s likely this risk will act as a substantial headwind for HAL’s shares over the next 2-3 quarters until there’s further evidence of stabilization or an upturn in the North America cycle.

One of the reasons I listen to or read transcripts, of conference calls from the likes of HAL and SLB every quarter is that management teams at these firms offer substantial big picture “macro” commentary about the industry. Generally, SLB has an unparalleled understanding of the international market while HAL rules in North America.

Here’s what HAL had to say about the US market during its Q4 2023 Call:

Analyst Question: Yes, good morning, Jeff, team. Appreciate the time. The first question is around — more macro question, which is one of the things that surprised us last year was the exit to — exit of U.S. oil production, which came in above I think where consensus expectations were. You have unique visibility into the U.S. completion and volumes. What do you think happened there? And as we think about 2024, how do you think about the exit rate of U.S. growth? Maybe talk about the moving pieces including DUCs?

HAL CEO Jeff Miller: Yes. Look, if I’m thinking about production growth in ’24 production is a function of service intensity. So simply put, more sand, more barrels, and we saw peak levels of service intensity throughout last — really in the first half of last year, and a lot of that comes on in the latter half. And I think some of this is efficiency in the sense that we are delivering more sand to the reservoir. And that comes in a lot of forms. The e-fleets are part of that, and some of the technology that we’ve brought to market.

But I also think that the market that we see for next year, it’s hard for me to forecast at this point exactly what operators will do because every operator plays their own game. But at the same time, I would probably take the over on rigs because I think that, we’ll run out of DUCs at some point. I think I would take the under on production only because whatever you think it is, I’ll take the under only because what we see are stable customers delivering their plans, but what we don’t see is a lot of the smaller companies coming into the market to really amp up production.

So I think, from our perspective at Halliburton, very stable market. But from a production standpoint, as we watch it unfold, it’ll be a matter of how much incremental sand gets pumped to overcome what is clearly going to be a decline rate that comes with, when we add barrels rapidly, obviously, they fall off rapidly.

Source: HAL Q3 2023 Earnings Conference Call Transcript

HAL’s CEO describes the evolution of the US shale business in 2023. At the beginning of the year, there was a surge in drilling and completion activity primarily driven by smaller operators – including many private companies – that were looking to grow production and, in many cases to dress up their businesses for sale. And, as I noted earlier, there was substantial M&A, particularly in the Permian, and targeting private operators in 2023.

When you boost drilling and completion activity, it takes a quarter or two for that to “show up” in results in the form of a surge in production; therefore, as Mr. Miller explains there was a surge in US oil production in the second half of last year and production was above expectations at year-end.

However, there’s a hangover from this.

As HAL indicated, activity slowed in the second half of last year, and, in early 2024 at least, HAL did not see the smaller producers accelerating activity to increase production.

Shale wells have high decline rates, meaning that production usually commences at a high initial rate but slows dramatically in the first 12 to 24 months after a new well is drilled. So shale producers are on a treadmill — a producer must drill some wells just to offset declining production from older wells, what’s known as the base decline rate.

So, heading into next year, HAL’s CEO is taking “the under” on production as the base decline rate eats through the surge in late 2023. HAL’s view is that some late 2023 surge in production will fade as 2024 progresses due to the drop in drilling and completions activity since the middle of last year.

He’s taking “the over” on rigs as producers seek to stabilize production declines heading into 2025.

In addition, the term “DUC” is an acronym for Drilled Uncompleted wells – these are wells that have been drilled but have yet to be fractured and put into production. Producers tend to build their inventory of DUCs when commodity prices are low; rather than put wells into production immediately, the company waits for a more favorable pricing environment.

HAL’s CEO believes the industry is running low on DUCs, meaning that producers will need to put more rigs to work and boost activity levels to increase production by 2025.

The EIA’s Drilling Productivity Report contains estimates of the total number of DUCs in various shale fields. The EIA’s data is broadly consistent with HAL’s comments – in the Permian, for example, EIA estimated 886 DUCs in March of this year compared to 2,560 DUCs three years ago in March 2021 and more than 1,350 two years ago in March 2022.

Bottom line: The main driver of my “Hold” rating on HAL stock right now is that there remain significant short-term concerns about service activity in North America through 2024. That’s likely to remain a headwind until there’s clear evidence the cycle is turning.

International: In Brief

As I noted in the intro to this article, the main differentiating factor for HAL relative to a peer like SLB is its exposure to North America and, in particular, shale drilling and completion activity in the region.

In my experience, it’s the outlook for shale activity that typically drives relative performance between HAL and SLB, the two largest diversified oil services providers in the world.

The fixation on HAL’s North American business isn’t entirely justified as the company does have a large international business that, as I showed you earlier, has been showing steady growth even as North American revenues have come off their peak in late-2022 and early last year.

A major topic in the international services business this year is that the Saudi government ordered its national oil company, Saudi Aramco, to halt a plan to boost its total maximum oil production capacity from 12 to 13 million bbl/day by 2027. Saudi Arabia has been developing a series of projects in recent years and Aramco’s spending is a significant, growing source of revenue for oil service majors including SLB and HAL.

The obvious concern: Could Saudi’s decision be the leading edge of a significant slowdown in activity and capital spending outside North America?

In my view, this fear is even more overblown than near-term concerns about the cycle in North America. SLB is the oil service company most directly exposed to Saudi activity and management there issued a press release hours after the Saudi announcement.

Simply put, SLB reaffirmed its guidance for 2024, noting that the Saudi decision has no impact on projects currently underway. Rather, Saudi is suspending two offshore projects that have not yet started up.

It also seems that Saudi Arabia is shifting some of its activity and spending in favor of developing onshore natural gas fields in the Kingdom. And the fact is that developing natural gas fields in Saudi Arabia isn’t about exporting gas, it’s a stealthy way of increasing Saudi crude oil exports.

That’s because Saudi Arabia still generates a significant portion of its electricity via oil-fired generation facilities. According to data from the Energy Institute Statistical Review of World Energy 2023, Saudi Arabia generated 131.4 terawatt-hours of electricity from oil in 2022, the most of any country in the world and about one-third of its electric generation in the same year.

By building a new natural gas generation capacity, designed to use gas produced within Saudi Arabia, the country can reduce domestic oil demand, freeing up as much as an additional 1 million bbl/day of oil for export by 2030.

And HAL’s own comments on its Q4 2023 call suggest growth in international CAPEX and activity is broad-based by geographic region. CEO Jeff Miller noted that HAL has been having discussions with international clients regarding projects that won’t begin until 2025 or 2026 and have durations of 3-4 years. That gives HAL increased visibility and confidence in international revenues and growth through the end of the decade.

Nevertheless, this remains an incremental sentiment risk for all services firms in the near term.

Conclusions and Long-Term Target

As I indicated, I’m rating HAL a hold for now due primarily to the headwinds posed by widespread concerns over revenue momentum and margins in the company’s massive, differentiated North American services business.

I believe risks to the stock will be elevated around the company’s quarterly earnings reports through the middle of this year, including their earnings announcement due out this week (April 23). Their statements will be parsed for any signs of softness in demand or a loss of pricing power in North America.

Earnings results from the likes of ProFrac discussed earlier, and due to report on May 9 could also represent a headline risk for HAL.

Regardless, my view remains that HAL’s North American business is well-positioned to benefit from more stable growth and profitability due to its ZEUS e-frac offering and the ongoing shift in its customer base in favor of larger, more disciplined producers. The company will also benefit from ongoing growth in CAPEX outside the US; while HAL’s international business isn’t as large as SLB’s, it’s one of the largest in the world and is showing broad-based growth.

Let’s take a rough look at what HAL could be worth moving into 2025:

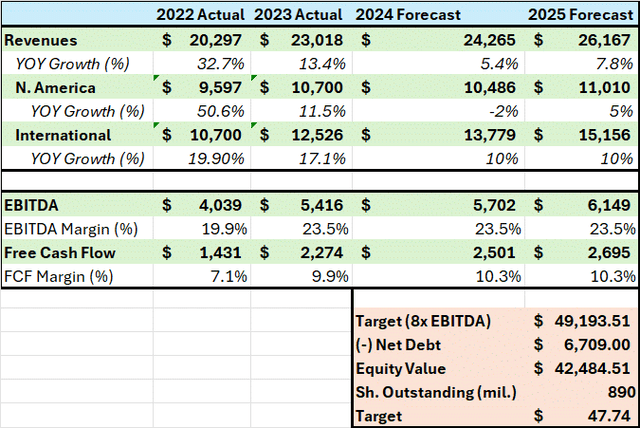

Revenue and Target Price for HAL (Bloomberg, HAL Q4 Conference Call)

During HAL’s Q4 call, management indicated North American revenues and margins would be flattish in 2024 from 2023 levels, so I’ve penciled in -2% growth in 2024 based on the recent pullback in North American activity.

Management also indicated international revenues were up “low-double digits,” so I penciled in 10% growth in revenues outside the US. That adds up to overall revenue growth of 5.4% to $24.265 billion in 2024, which is close to in line with the Wall Street Consensus per Bloomberg of $24.26 billion.

I’m assuming a flat EBITDA margin for 2024, in line with the 2023 level. As for free cash flow, HAL indicated that it would expand “at least 10%” from the 2023 level, which implies an FCF margin of 10.3% in 2024 on my revenue estimates, slightly higher than in 2023. That makes sense as HAL has been focused on holding annual CAPEX at about 6% of revenues over the long haul, which has had the effect of increasing its free cash flow margin in recent years.

For 2025, I’m factoring in the return of some modest growth in North America, around 5%, due to the potential for an inflection in drilling and completion activity into 2025 along the lines I outlined earlier. I’ve maintained international revenue at +10% based on steady growth in that business.

Based on these (rough) estimates and flat margins, HAL’s EBITDA could expand to over $5.7 billion in 2024 and $6.15 billion in 2025.

Based on monthly data, HAL’s average enterprise value to one-year forward EBITDA multiple over the past two years has been around 8x, and if we apply that multiple to our 2025 EBITDA estimates we derive a value of $47.75 per share for the stock, a 22% premium to HAL’s close last week.

I see these estimates on the conservative side for 2024; however, I am penciling in the resumption of significant growth for 2025. I believe the potential for growth in 2025 is unlikely to get much credit in markets until the second half of this year as we see some signs of a ramp in shale-directed activity and further signs of stable growth internationally.

Bottom line: North America headwinds will likely restrain the stock through the first half of 2024 though I believe we’re setting up well into 2025 and a 12-month target in the upper $40s as I’ve outlined seems reasonable.

For now, HAL is a hold until we get confirmation of that second-half turn.

Analyst’s Disclosure: I/we have no stock, option or similar derivative position in any of the companies mentioned, and no plans to initiate any such positions within the next 72 hours. I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it (other than from Seeking Alpha). I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.

Seeking Alpha’s Disclosure: Past performance is no guarantee of future results. No recommendation or advice is being given as to whether any investment is suitable for a particular investor. Any views or opinions expressed above may not reflect those of Seeking Alpha as a whole. Seeking Alpha is not a licensed securities dealer, broker or US investment adviser or investment bank. Our analysts are third party authors that include both professional investors and individual investors who may not be licensed or certified by any institute or regulatory body.