Summary:

- Seeking Alpha analysts are cautious on Nvidia Corporation stock, with 22 rating it as a hold, 13 as a sell, and only 12 as a buy or strong buy.

- The bear theses revolve mainly around the stock’s valuation. Dismissing a stock with Nvidia’s secular tailwinds purely on valuation could be a mistake.

- This article aims to provide a more nuanced approach to valuing Nvidia by looking at historical cases and discussing the risks investors should monitor.

Don’t be too quick to dismiss Nvidia because of valuation da-kuk

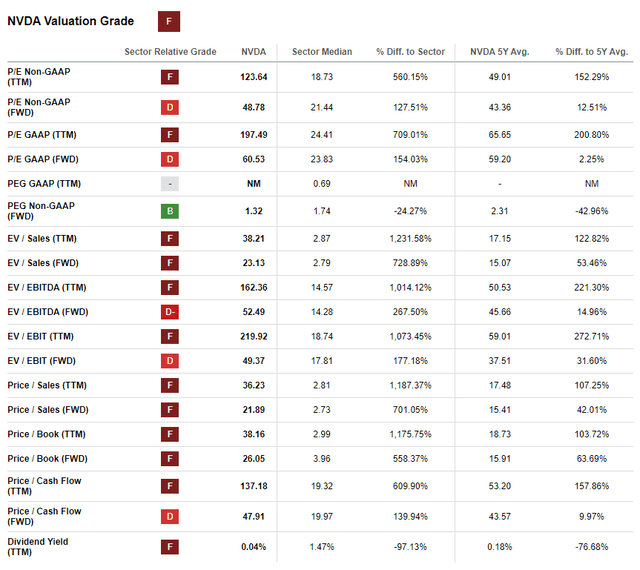

Despite its meteoric rise this year (or maybe because of it), Seeking Alpha analysts have grown careful on Nvidia Corporation (NASDAQ:NVDA) stock, at least according to analyst ratings. 22 analysts rate it as a hold, with 13 giving it a sell rating while only 2 assign NVDA a strong buy rating, with 10 other buy ratings as of the time of writing. The majority of the bear theses revolve around the stock’s ballooning valuation, and they certainly have a point; Nvidia stock trades at 60x forward earnings, with the sector median at 23.

Nvidia gets a valuation grade of F (Seeking Alpha)

This article, however, will try to offer some of the nuance regarding why looking at quantitative valuation metrics for a stock like Nvidia may lead to a reductive conclusion. It will look at two historical cases that might provide some lessons on how to approach Nvidia. The hope is that those cases can help investors have a more nuanced approach to valuing Nvidia. But the ultimate decision on whether this stock is a buy or not will be left to them.

Having said that, I do rate Nvidia Corporation stock a buy. I will explain my reasoning at the end of the article and point out the risks I believe are relevant to investors other than valuation.

Valuations Do Not Move Stocks, Fundamentals Do

Many investors can point to events like the dot com bubble as clear indication that, at least at the extremes, valuations do have an impact on future returns. There is Robert Shiller’s famous book Irrational Exuberance that essentially won him the Nobel Prize and is dedicated to examining bubbles. The timing of the book’s publishing (in the year 2000 with the popping of the dot com bubble) seemed to drive home the point that unrealistic valuations can indeed end badly for investors.

A favorite investor of mine who discussed the importance of valuation is Mohnish Pabrai. At an investing event in June of last year, he discussed how extreme valuations can lead to unpleasant consequences for investors. He said the following about Microsoft Corporation (MSFT) in 2000:

I remember in early 2000, I visited Microsoft headquarters. I had an early investor who wanted me to come, he wanted to introduce me to other possible Microsoft people to possibly invest with me. I made a trip to Seattle, and I went to Microsoft. I was talking to a lot of these people and of course, in what they had seen from 1976 until 2000 was just a straight, nonstop upward trajectory of Microsoft. Nothing else. They continued to believe that would continue to do well. I told them that it was probably not the smartest thing in the world for them to have all their income coming from Microsoft and 90% of their net worth in Microsoft stock or something. They just looked at me like, you really don’t understand the company or whatever. the thing is, it was extreme. Microsoft’s market cap at that time was amongst the three largest market caps in the world. I think north of 600 billion. The cash flows they were generating were single digit billions something. It was trading at like 70 to 80 times earnings, something not growing that much. But it was a very good business. I told them, the business will keep doing well, but everything has a price and everything has a value.

Microsoft peaked at a split-adjusted $59.97 in 1999 before crashing. It was only in 2016 that it managed to return to those highs.

This certainly does prove a point; valuation, at extremes, can have negative consequences for investors. It was evident in the stock performance of Microsoft and many others. The business did well, but the stock didn’t respond. Pabrai continues:

In 1999, 2000, it was a time when there was a massive bubble in dot com. There was also a bubble in stocks like Coke, General Electric, and Microsoft. These companies had real earnings and such. But even they were very stretched valuations.

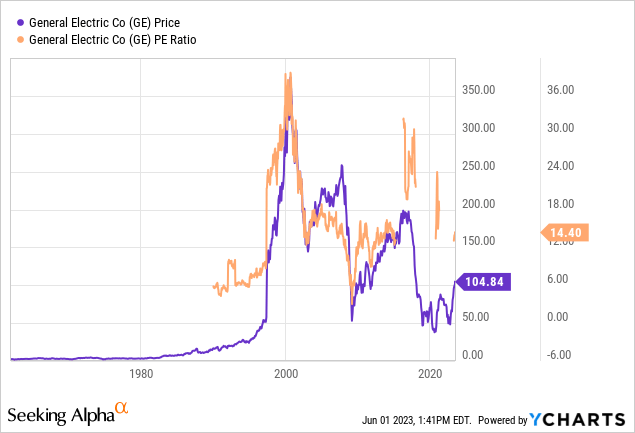

The trouble with that take however is that it could lead to its own errors in judgement. Because if the reason for the decline in the stock prices of those companies was because they were richly valued, then it might be safe to assume that they are a better bet when they are cheap. Yet General Electric Company (GE) never recaptured its dotcom highs, and The Coca-Cola Company (KO) hasn’t even doubled from its dot com highs 23 years later. Microsoft, meanwhile, has roughly grown 5.5 times from the same peak. So, valuation alone does not explain the performance of those three stocks.

So, as the chart shows, there is certainly some truth to the impact of valuation at extremes. At 36x earnings, GE was a terrible buy. But at 4-5 x earnings, it was a good one. The question is what constitutes an extreme? Because the stock did well for a while at 24x earnings for example, and it did very poorly despite being at 12x earnings in the early 2000s. And even when it was at single digit P/E valuation, it significantly underperformed Microsoft which was more expensive.

So, there has to be another layer of analysis applied on top of valuation before making a final decision on whether an investor knows what lies ahead for a given investment. I hope this comparison between Microsoft and arch-rival Apple Inc. (AAPL) will drive this point home.

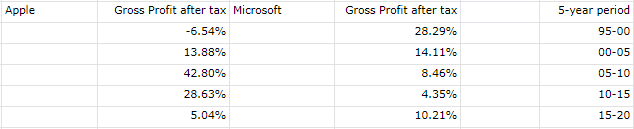

Microsoft struggled because the business slowed (Created by author using regulatory fillings)

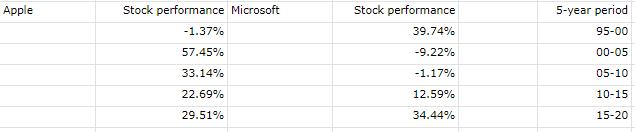

This table compares the average growth in gross profit after tax over five-year intervals for both Apple and Microsoft from 1995 to 2020. I chose gross profit after tax because I believe it shows us what each company made for its investors, stripping out any difference in investing intensity or capital structure. It is purely the outcome of what the business generated from selling its goods and services. You can see in the table that Apple underperformed Microsoft from 1995 to 2005, before dominating in the 10 year period after, and that Microsoft did better in the five-year period ending 2020.

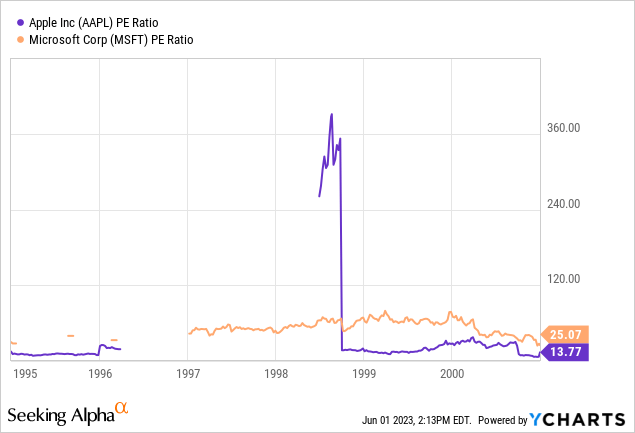

In 1995-2000, when Apple underperformed Microsoft in terms of gross profit growth, it was the cheaper stock. But as I will show in the next table showing stock returns compounded annually, it underperformed Microsoft. This shows that the business performance (in this case gross profit after tax growth shown in the table above) might have done a better job explaining stock performance compared to valuation.

Stock performance seems to be driven by business developments rather than valuation (created by author using TradingView)

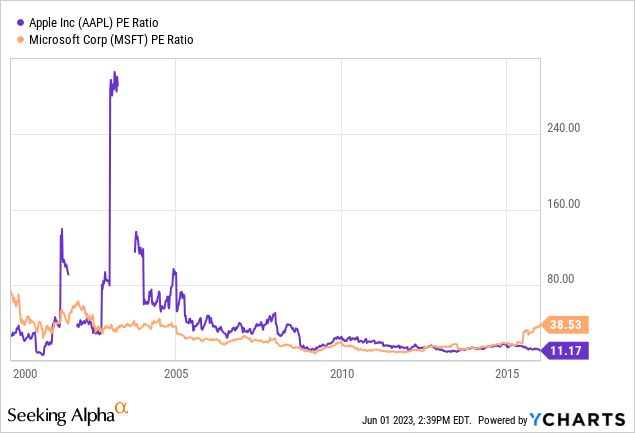

There are a number of observations I take from the two tables: 1) Microsoft’s growth in gross profit after tax had decelerated in each 5-year period until 2015-2020. This mirrors to some extent the top in the stock in 1999, the lull in the stock in the early 2000s before reaching an all-time high again in 2016. 2) Admittedly, it’s a small sample, but Apple’s stock generally outperformed Microsoft when it grew faster and vice versa (the exception was in 00-05 period).

Had it been solely valuation and its extremity that determined future performance, we would have had the opposite result. Ironically, Apple’s P/E was higher than Microsoft when it started outperforming it. And Microsoft’s stock started to get more expensive than Apple when it started outperforming in the 2015-2020 period. So, had investors relied on relative valuation to pick between the two stocks, investors would have generally picked the loser as a result.

For me personally, I don’t believe that Microsoft’s stock struggled in the aftermath of the dot com era because it got to extremely high valuations necessarily, but instead because the company missed important business trends like the smartphone, e-commerce, and search. Meanwhile, Apple thrived despite its relatively higher valuation in the early 2000s because it capitalized on developing iPods with the introduction of the iPhone, the iPad, as well as its services business.

Applying that to Nvidia, and even if its stock ends up declining, it could be a mistake to pin that purely on valuation. Instead, investors must try to make educated guesses over the AI market and Nvidia’s competitive position in it, and how that can affect the stock. For some insight into what the future might hold in that regard, I believe there is value in revisiting the QUALCOMM Incorporated (QCOM) story with the rise of smartphones.

It’s The Qualitative Analysis That Matters

2007 seemed like a mundane year for Qualcomm; the stock was up a mere 4% on the year, and it was still down 60% from its all-time high reached seven years earlier. In retrospect, however, 2007 proved a transformational year for Qualcomm: it’s the year Apple introduced the iPhone. It is also the year the company introduced its Snapdragon chip that would go into most non-Apple smartphones. Yet the stock hardly moved at all. Though it’s hard to know for sure why, the stock barely moved in response to these developments because it wasn’t clear in 2007 that smartphones will be good for Qualcomm’s business. The company dominated licenses for 2G, But it was not clear if it can be a leader in 3G.

In a fantastic article, Sramana Mitra approached Qualcomm’s investment thesis the way I hope investors approach Nvidia today:

Does Qualcomm’s WCDMA royalties compare with what they have in CDMA? Will it be a meaningful substitute financially? And will WCDMA win over and / or be an essential component of 3G/4G GSM in the long run?

This article was a little skeptical on Qualcomm’s chances (though it was open to the possibility of Qualcomm succeeding). And although the downbeat sentiment on Qualcomm in the article did not materialize, the author asked all the right questions that would help investors make a decision. It didn’t simply dismiss Qualcomm because it traded at 20-25x earnings, it examined the competitive landscape and Qualcomm’s position in it before suggesting that the company could struggle.

Meanwhile Bear Stearns’ Avi Silver was more optimistic. He believed the company could sell up to 300 million WCDMA handsets in 2008. He also said that he expected the company’s EPS to compound at 15-20% over the next 3 years and gave the stock a price target of $48.

In fiscal year 2007, Qualcomm reported $3.3 billion in net income on $8.9 billion in revenue. By 2010, Profits were actually down to $3.1 though revenue crossed the $10 billion mark. Yet the stock was up to $49.49 by 2010 compared to $39.35 by the end of 2007, mainly due to this:

the company is now firmly expecting that it will be able to raise its revenue and EPS by at least 10% for the next five years. This positive momentum is mainly due to the unprecedented surge in global demand for 3G smartphones.

By 2022, profits had grown from $3.1 billion in 2010 to almost $13 billion, compounding at almost 13% over 12 years rather than the 10% over five years that management in 2010 expected. Earnings per share compounded at more than 15% over the period, helped by buybacks. The stock also more than doubled over the period and the dividend yield on stocks purchased at the end of 2010 is 6.5% today. This all happened despite the earnings multiple contracting from 25x in 2010 to 9.7x in 2022.

Nothing about what Qualcomm ended up doing required extraordinary foresight. In fact, all you needed was to believe what they said on page 6-7 of the 2007 annual report, rather than fixate on the valuation or the real-estate bubble at the time:

In addition to the tremendous demand for wireless voice services, wireless service providers are increasingly focused on providing broadband wireless access to the Internet, as well as multimedia entertainment, messaging, mobile commerce and position location services. These services have been aided by the development and commercialization of 3G wireless networks and 3G handsets which are capable of supporting higher data rates that incorporate an ever-increasing array of new features and functionality, such as assisted GPS-based position location, digital cameras with flash and zoom capabilities, internet browsers, email, interactive games, music and video downloads and software download capability (e.g. our BREW platform). In October 2007, the Yankee Group, a global market intelligence and advisory firm in the technology and telecommunications industries, estimated that more than 2.5 billion people will be using mobile data services by 2011 and the revenue produced from these services will account for 23% of total service revenue worldwide. We believe the growing availability of 3G-enabled handsets capable of performing a wide variety of consumer and enterprise applications will accelerate the demand for many wireless data services on a global basis and thus lead to an increased replacement rate of mobile devices to those using our technologies and integrated circuits. Affordable wireless broadband data connectivity is important to the consumer and enterprise, and its demand will continue to drive the evolution of wireless standards.

This chart is a good summary of the points raised earlier. Investors could have picked the absolute top of the dotcom bubble in Qualcomm and still made some money today. Well, what if they waited for the bubble to burst? Technically it never did, the valuation at the lows of the dot com bubble was 44x earnings. Despite that, the stock grew 10-fold in almost 21 years, a compounded return of 11.6% excluding dividends. The morale of the story is investors will do well to buy good businesses and hold on. That’s because the earnings in 2002 were based on a completely different business to the ones earned in the 2010s. The numbers are simply not comparable. That’s where Nvidia’s story draws some similarity with Qualcomm’s.

The Case For Nvidia

The investment case for Nvidia today is just as straightforward as it was for Qualcomm in 2007. Without the use of any jargon to keep it simple, the introduction of ChatGPT is sparking a move from a world where software applications relied on the computing power of the device, to one where they rely on the computing power of servers in data centers. For that, companies need: 1) Processing chips that can do things faster 2) Connect as many chips together as possible to increase the computing power further and deliver spectacular software applications like ChatGPT, Midjourney and the like. 3) Support in building these new AI applications.

Nvidia is so far the only company that delivers all three needs, and it’s also the leader in all three. Note that this shift isn’t only related to creating AI chatbots, it applies to autonomous vehicles, genomics, and gaming.

Jensen Huang said the following in the latest earnings call:

[W]hen generative AI came along, it triggered a killer app for this computing platform that’s been in preparation for some time. And so, now we see ourselves in two simultaneous transitions. The world’s $1 trillion data center is nearly populated entirely by CPUs today, and $1 trillion, $250 billion a year, it’s growing of course. But over the last four years, call it a $1 trillion worth of infrastructure installed. And it’s all completely based on CPUs and dumb NICs. It’s basically unaccelerated. In the future, it’s fairly clear now with this — with generative AI becoming the primary workload of most of the world’s data centers generating information… you’re seeing the beginning of call it a 10-year transition to basically recycle or reclaim the world’s data centers and build it out as accelerated computing.

So not only should Nvidia be a $1 trillion market cap, but it should also topple Apple as the world’s most valuable company if what Huang said turns out to be true. The question becomes, why is Nvidia trading at just below $1 trillion, rather than at almost $3 trillion like Apple?

Risks

The answer is Apple accrued enormous economic value by locking in its customers, and it’s unclear Nvidia will be able to keep its customers locked in. The first thing to note is that there has been cyclicality to the demand for Nvidia’s inventory compared to Apple’s services for example. Huang could end up being right about the next 10 years, but that doesn’t mean that demand for the company’s products will be in a straight line upwards. It may experience times of oversupply that drives margins (and its stock price) down.

Then there is the matter of the processing chips architecture themselves. Nvidia faces competition from traditional chip designers like Advanced Micro Devices, Inc. (AMD) and Intel Corporation (INTC). It is also facing competition from startups like Graphcore. Then there are big tech firms who are all developing their own chip. All these firms combined could end up taking significant share from Nvidia. But for any of those companies to truly displace Nvidia, they have to meet needs number 2 and 3 as well. For now, its Nvidia’s ability to meet those two needs that represents its competitive advantage. But it’s still open whether they can maintain that advantage in the long run.

And those are the risks if Huang is right. There is the possibility of this being a honeymoon period. Everyone saw how great ChatGPT is and decided to try their hand at their own AI apps, and Nvidia is benefitting from that now. It is very possible though that interest in developing these apps will wane if companies realize their interests are better served going back to doing what they do best. In that case, Nvidia might be left with a glut of GPUs that it doesn’t know how to sell.

Conclusion

Longer term, the stock performance of Nvidia Corporation will not necessarily depend on its initial valuation. It will rather depend on Nvidia’s ability to stave off competition from different type of processing chips architecture and networking, in addition to continuing to offer the software tools that developers need for AI applications. For now, Nvidia stock is a buy given the company is a clear leader on all three fronts with no sign of that changing in the short to medium term. When the facts change, I will change my mind and it will be time for another Nvidia article.

What about Nvidia Corporation valuation? Well, if investors are worried about that but believe the fundamentals are great, they might be better served investing in Nvidia stock in small portions over time rather than avoid a great business all-together. Surely this way, with bad luck not interfering, they will invest at times of good valuation just as much as they do at times of high valuation.

Analyst’s Disclosure: I/we have a beneficial long position in the shares of NVDA either through stock ownership, options, or other derivatives. I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it (other than from Seeking Alpha). I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.

My position is a short put option in Nvidia rather than a call or ownership of the shares. My strike price is at $310.

Seeking Alpha’s Disclosure: Past performance is no guarantee of future results. No recommendation or advice is being given as to whether any investment is suitable for a particular investor. Any views or opinions expressed above may not reflect those of Seeking Alpha as a whole. Seeking Alpha is not a licensed securities dealer, broker or US investment adviser or investment bank. Our analysts are third party authors that include both professional investors and individual investors who may not be licensed or certified by any institute or regulatory body.