Summary:

- Intel’s dividend suspension aims to strengthen its position amid existential threats.

- The company is struggling to compete with rivals like AMD and NVIDIA, particularly in AI and PC markets.

- Intel’s efforts to attract fabless semiconductor customers haven’t translated into financial success, with operating losses in the foundry business deepening.

- Despite the expected rebound in PC sales, Intel’s reputation and strategic positioning remain challenged.

hapabapa

Investment Thesis

I’ve never been as torn on a stock as much as I am on Intel Corporation (NASDAQ:INTC). The August dip, largely tied to the market’s reaction to the company’s dividend halt seems irrational. Intel is facing intense competition in a rapidly evolving market. Its problems are existential, and suspending dividends to free cash to strengthen its position is a positive catalyst in my eyes. The market doesn’t seem to agree with this assessment.

But then, the fact that Intel is facing an existential threat is enough for a sell rating. The company missed its opportunity to monetize the AI trends that are benefiting its competitors.

Intel’s troubles extend beyond its Q2 earnings miss. It is about reputation, human capital, and industry trajectory. University students are learning CUDA, not Intel’s Synapse AI. They’re familiarizing themselves with Arm Holdings plc (ARM) Advanced RSIC, not Intel’s x86. In an industry where talent is the most valuable asset, these are strategic threats.

I get it. In business, there is rarely a winner-takes-all. But then, with the wide technology moat, manifested in the software frameworks around competing data center products, I think winner-is-taking-most, leaving Intel scurrying after the crumbs.

In the Personal Computer ‘PC’ space (laptops and desktops), Intel is fairing a little bit better, but still playing defense.

Wasted Time

When Patrick Gelsinger became CEO of Intel in 2021, one of his key decisions was to fully open Intel’s manufacturing facilities to external orders from fabless semiconductor companies – those that design chips but don’t have their own facilities. Many companies, including NVIDIA Corporation (NVDA), Advanced Micro Devices, Inc. (AMD), and Broadcom Inc. (AVGO), outsource manufacturing functions to third-party companies, called foundries, such as Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company Limited (TSM), GlobalFoundries Inc. (GFS), United Microelectronics Corporation (UMC), among others. Gelsinger thought he would increase Intel’s revenue streams by providing manufacturing services to these companies. What he didn’t think about was whether these customers would want to come.

Companies along the semiconductor supply chain work closely together. A chip manufacturer needs to know the chip design and the technology roadmap for future products to prepare the assembly lines and order equipment from likes of ASML Holding N.V. (ASML), Applied Materials, Inc. (AMAT), and Lam Research Corporation (LRCX). Everyone needs to be open and share sensitive information about their capabilities, limitations, and future plans.

Intel is a chip designer and has products that compete with these fabless companies. Why would, say AMD, want Intel to manufacture its Ryzen CPUs if this means giving away the secret designs and technology roadmap to their competitor?

Gelsinger made solving this problem a top priority. He spent a lot of time this year trying to create a structure in which its manufacturing facilities operate at arm’s length of its core chip design business. This meant separating Human Resources, Enterprise Resource Management, managerial, procurement, and strategic apparatus of Intel Fabless and Foundry business lines.

Did it work? Who knows and who cares? Whatever he does, fabless customers won’t come, at least not those competing with Intel, which is effectively every semiconductor company except perhaps those designing memory chips, the least lucrative of all microchips, whose capacity seems to always be in oversupply mode. (Intel exited the memory market years ago)

To be fair, last month, David Zinsner talked about some customers coming for packaging services, saying that this wasn’t expected, and noting that this will allow Intel to build relationships with these customers in the hope that they would in the future outsource their wafer fabrication needs to Intel. I don’t think we should draw conclusions from Intel’s chip packaging customers. It’s a different game than wafer fabrication, requiring less design collaboration.

I think the main benefit of the reorganization work done this year is clarifying the financial boundaries of the two segments, and determining who’s carrying their weight and who’s not. Think Kaizen Cost Accounting, nothing less and nothing more, in my opinion. But to be fair, this could come in handy if and when (and hopefully) Intel decides to sell its foundry business.

Financially, whatever Mr. Gelsinger did for the foundry business hasn’t translated to financial gains. Operating losses deepened for the Foundry segment in the six months ended June 2024 to -$5.3 billion loss, up from -$4.2 billion loss in the same period of last year.

The Future of Personal Computers: Intel’s Opportunity

The separation initiatives took valuable time and money that Intel could have allocated to more strategically pressing problems; the rising star of AMD Ryzen CPUs, and other personal computer ‘PC’ CPU brands, Intel’s core revenue stream for decades. Desktop and laptop CPU sales constituted 62% of total product revenue this year, which is in line with the historical average.

This restructuring noise is particularly concerning as the market moves toward the next generation of AI-powered laptops/desktop CPUs, a pivotal transition that opens a rare opportunity for Intel to reclaim its throne in the market.

Intel released the Intel Core Ultra last year, which features a neural processing unit designed for localized AI applications. Until now, AI applications mostly ran on the cloud, accessed via the browser. But the era of AI-powered operating systems is already here. The iPhone 16 A18 chip comes with an embedded neural network unit, and local AI applications might start on Mobile devices but will soon come to laptops and desktops, this requires AI-enabled CPUs, and Intel has to be prepared. The Core Ultra CPU is a good start, but there are a lot of uncertainties. Will Intel regain market share in the PC CPU market? What is certain is that the Ultra brand will cannibalize the non-AI Intel Core CPU sales. So, this AI potential tailwind is more about Intel reclaiming market share as opposed to opening up a new market opportunity or expanding the Total Addressable Market ‘TAM’. The good news is that Intel Core Ultra sells at a higher price and profit margin than a traditional CPU, so that’s a plus in the medium run (but, apparently not in the short run, because of production ramp-up costs).

Adding to the Core Ultra troubles last quarter was the manufacturing blunder tied to speeding up mass production of Core Ultra and the hasty transition of Ultra production from lap settings in Oregon to mass production in Ireland. This is largely the reason Intel’s profitability disappointed the market last quarter. It is a one-time setback, so, we should see gross margin improvements next quarter. But it is certainly an embarrassing blunder. They basically wanted to cut corners to save some money, and this backfired massively.

Beyond the strategic threats, we now see a rebound in the PC market, with PC chip sales up 18% YoY this year, as Dell Technologies Inc. (DELL), HP Inc. (HPQ), and Lenovo Group Limited (OTCPK:LNVGY) recover from the inventory buildup tied to the pandemic supply chain disruptions.

From a technological standpoint, I think consumer behavior is heavily influenced by the reputation of the manufacturer. While Intel remains a strong player in the laptop/desktop CPU market, a lot of the things that they do aren’t noticeable to everyday users. For example, Intel was the first to optimize the ‘wake-from-sleep’ lag in laptops and desktops, but beyond the CPU enthusiast, it is very difficult to compare these minutiae features.

On the other hand, Intel has been lagging where it is most visible. For example, when they were struggling to manufacture the 7 nm nodes, AMD was mass-producing their 5 nm Ryzens with the help of TSM manufacturing capabilities. AMD also started the race in core and thread counts, and they always seem one step ahead. For example, this year, Intel announced the latest Intel Core i9, touting its 24 cores like it’s something new. AMD has been selling its 24-core Ryzen CPU since late 2019. For an average user, these cutting-edge features don’t matter much. But then, with a large number of CPU brands, reputation matters, and Intel is losing this game, dampening the returns on its CapEx and R&D dollars it spends to catch up.

Is the market too pessimistic?

There is certainly a disconnect between Intel’s fundamentals and its share price, mirroring the pessimism over Intel’s future prospects. This year’s share price decline was accelerated in August after Intel announced suspending dividends (starting in Q4 24), and the layoff of 15,000 employees. Personally, I see dividend suspension as a positive catalyst, but apparently, others don’t agree. Intel is in survival mode and can’t afford to pay dividends. Instead, it should focus on rebuilding its technology platform to remain relevant, and that’s what they are doing. I think investors should be celebrating the dividend cut. Yet, shares are down 53% this year.

Between 2022 to date, Intel’s share price decline outpaced that of its revenue decline. For example, in this period, Intel’s shares were down 53%, compared to a 34% sales decline.

But we see mixed signals in terms of valuation. Sure, the 2025 Forward PE ratio is about 20x, which is below the industry average, but it is hardly a bargain, especially in light of the growth and profitability challenges facing Intel.

Some fellow analysts cited the Price/Tangible Book Value of 0.83x as an interesting argument for Intel’s undervaluation since it means that Intel’s share price trades below its intrinsic value, but then, a significant portion of these assets are tied to its unprofitable foundry business.

AI and Data Centre

Intel is facing pressure from all sides. Its PC CPU segment is threatened by AMD’s Ryzen and even QUALCOMM Incorporated (QCOM) is now making PC CPUs, leveraging its energy-efficient mobile platform to expand into Intel’s turf. Arm Holdings plc (ARM) is threatening the very core of Intel’s x86 platform that historically created a moat around its chips.

In the data center segment, Intel is competing on price. They launched Gaudi, an AI accelerator able to perform AI large language modules inference and training functions, directly competing with NVIDIA and AMD. Xeon CPUs also come with neural network units capable of supporting certain AI workloads (but not inference and training).

We often hear that in business, there is no winner-takes-all. Maybe. But for Intel, regardless of its product capabilities and price, penetrating the CUDA moat is very difficult in the short and medium terms. NVIDIA has been building CUDA for general-purpose computing on graphics processing units ‘GPGPU’ for parallel computing for decades.

It is worth noting that Intel entered the GPU market in 2020 with the introduction of Xe GPU, followed by Intel Iris and Intel Arc, all of which are discreet GPUs used for graphics functions, as opposed to general computing.

Costs, CapEx, and R&D

Intel is attempting to regain its leadership partly through heavy investments in its foundry business. The company recently announced a new node technology, the 18A, with plans to roll out the first 18A-based CPUs, GPUs, and Accelerators in 2025. But, from management’s comments, we should see more flexibility in outsourcing intel designs to third-party manufacturers. The whole thing is a bit confusing. You either invest in a foundry and use it, or sell it and outsource manufacturing. Otherwise, why waste shareholder’s money?

Net CapEx is expected to come down slightly in 2025. The company is selling equity interest in some of its business lines which lowers the net CapEx forecasts in 2025. For example, in 2022, they IPO’d Mobileye Global Inc. (MBLY), the autonomous driving chip manufacturer it acquired in 2017. Intel also sold a minority stake in Intel Memory Solutions ‘IMS’ and announced it was running the Programmable Solutions Group ‘PSG’ as a standalone business to pave a path for a similar equity transaction. It is worth noting that a significant part of IMS revenue is tied to intellectual property licensing. Intel is also eligible for federal tax and cash grants for its manufacturing facilities under construction in the US.

All in all, Intel expects 2025 net CapEx between $20 – $23 billion, about 10% to 20% lower than 2024 levels.

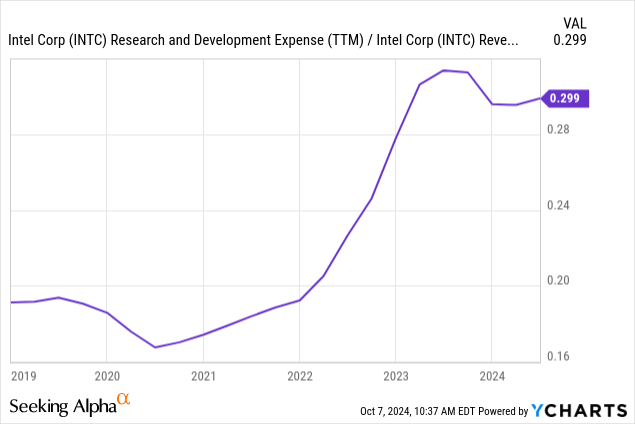

OpEx is also expected to come down after surging to historical levels in 2024. On a TTM basis, R&D as a percentage of sales reached 30% last quarter. During the Citi Technology conference last month, Intel’s CEO guided for OpEx of $17.5 billion in 2025, down significantly from recent years. Intel’s TTM OpEx this year is about $22.3 billion.

Final Thoughts and How I Might Be Wrong

Intel has the uncertainty of a startup and the bureaucratic weight of a blue-chip company, with the benefits of neither. The real money is, for the next decade, going to Generative AI GPUs. Intel’s AI accelerators might be cheaper, but they face a wide technological moat of popular frameworks such as CUDA and TensorRT.

Not only the core technology platform of x86 is under threat, but the very business model of combining a chip design and fab operations doesn’t make sense in this rapidly changing world. AMD was able to gain market share in the PC CPU market because it wasn’t confined by the limits and interests of a fab. It outsourced production and subscribed to the latest technologies offered by third-party foundries.

Meanwhile, Gelsinger is trying to maximize the profits of his foundry business at the expense of the chip design business. The Ireland Core Ultra manufacturing blunder is just embarrassing.

Going into the second half of 2024 and FY 2025, I think we should see higher impairments, reorganization, and restructuring charges, increasing the complication of the financial reports, and further adding to the confusion surrounding Intel.

Editor’s Note: This article discusses one or more securities that do not trade on a major U.S. exchange. Please be aware of the risks associated with these stocks.

Analyst’s Disclosure: I/we have no stock, option or similar derivative position in any of the companies mentioned, and no plans to initiate any such positions within the next 72 hours. I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it (other than from Seeking Alpha). I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.

Seeking Alpha’s Disclosure: Past performance is no guarantee of future results. No recommendation or advice is being given as to whether any investment is suitable for a particular investor. Any views or opinions expressed above may not reflect those of Seeking Alpha as a whole. Seeking Alpha is not a licensed securities dealer, broker or US investment adviser or investment bank. Our analysts are third party authors that include both professional investors and individual investors who may not be licensed or certified by any institute or regulatory body.