Summary:

- Intel Corporation has revealed an ambitious financial roadmap through 2030, targeting a nearly 70% improvement in Intel Foundry’s operating margin. A monumental turnaround indeed.

- The stock market reacted negatively to the long-term outlook, but this was unfounded as the overall financial targets remained unchanged. Intel will likely also increase its process leadership with 14A.

- The internal foundry model exposes the manufacturing group as the main cause of Intel’s deteriorating margins, which the turnaround will reverse. The product groups remain profitable.

- The turnaround could be likened to AMD’s, with the 2017 Zen launch only marking the beginning of a new era of long-term growth and investor returns. Restoring tech leadership is only a prerequisite for investors.

- Overall, the webinar provided a strong case for returning the manufacturing side to profitability (and beyond), solidifying the case for a long-term investment.

JHVEPhoto/iStock Editorial via Getty Images

Investment Thesis

At its highly anticipated “New segment reporting webinar,” Intel Corporation (NASDAQ:INTC) revealed an ambitious financial roadmap through 2030, with as its headline the target for a nearly 70 percentage point improvement in Intel Foundry’s operating margin through the period.

However, as the stock market doesn’t like to look forward so far, the stock sunk because of this long-term reality, not unlike when the financial details of the turnaround were first disclosed in late 2021 ahead of the (early 2022) investor meeting. While there are certainly risks in succeeding in this aggressive goal, the main (high-level) takeaway is the incredible potential for improved profitability as Intel moves into the EUV era and regains process leadership.

Background

Intel first announced its plan to create the so-called “internal foundry model” in fall 2022. The aim was to split up the company in products and manufacturing without actually splitting up the company. In that way, the Intel product groups would become foundry customers just like any external foundry customer would. In that way, Intel Foundry would have to compete for Intel Products business just like any other foundry would, on equal footing (i.e., on price and process PPAC or power-performance-area-cost).

The idea was that this would more clearly expose the underlying financials, allowing for like-for-like comparisons of both businesses against their respective competitors, which would not only give more clarity to investors, but also to Intel’s management. After all, the idea behind being an IDM was to get “margin stacking”: instead of having to buy a foundry wafer at 50% gross margin (=2x the actual manufacturing cost), the so-called “foundry tax,” Intel as IDM only had to pay the actual manufacturing cost, and could then either undercut fabless competitors in pricing at the same gross margin at one end, or achieve higher gross margins at similar pricing. Add in Intel’s process leadership, which provided even more flexibility in power-performance and cost-gross margins, and Intel had a great recipe for industry domination, and hence shareholder returns.

However, looking at Intel’s more recent financials in the wake of the 10nm and 7nm delays and then the post-COVID-19 downturn, not much of this supposed IDM advantage seems to remain. Indeed, in leaked slides, Intel had done the exercise of cooking up a virtual Taiwan Semiconductor aka Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company Limited (TSM) – Advanced Micro Devices, Inc. (AMD) or TSMC – NVIDIA Corporation (NVDA) IDM, which showed that it would achieve much higher gross margins than either of them separately, and (perhaps even more worryingly) also much higher than peak Intel. So, IDM should still have an advantage in principle, but that just hasn’t been realized by Intel: besides loss of process leadership, the lack of scale is also detrimental as Intel overall has to absorb over $20B in R&D and SG&A fixed costs. This is, of course, the main thesis behind starting the foundry business. Nevertheless, as just mentioned, the TSMC-AMD virtual IDM comparison also showed Intel just seemed inefficient in its operation.

Overall, the internal foundry model doesn’t change the strategy, which is the 5N4Y to regain process leadership to strengthen long-term competitiveness and cost structure, as well as the foundry business as one of the new areas for long-term growth. Indeed, in my previous coverage (which in hindsight was a bit too pessimistic), I called it mostly a financial engineering gimmick.

However, for the first time in Intel history, it will quantify the extent to which the IDM margin stacking is actually realized, which might uncover previously unseen inefficiencies.

New segment reporting webinar

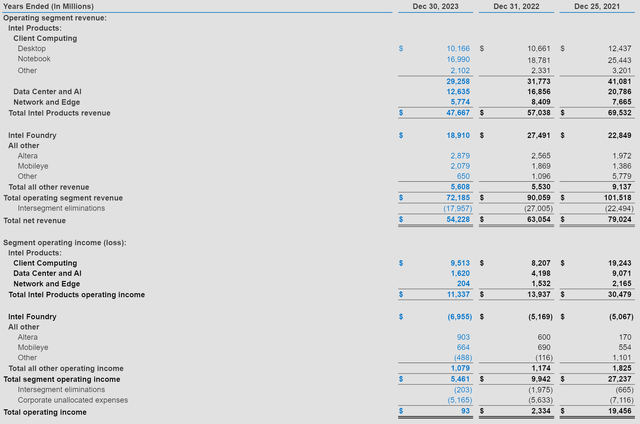

On April 2, Intel held its internal foundry model webinar. The released material, including press release, presentation, and webcast can be found here: New Segment Reporting Webinar. The recast financial results for the last three years are shown below.

Obviously, the overall P&L doesn’t change. Instead, what happens is that the internal Foundry “revenue” and “profit/loss” is at the end are subtracted as intersegment revenue and expenses.

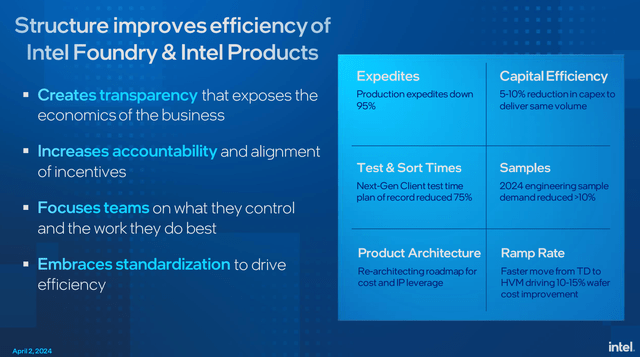

The main result of this exercise is that it exposes that the manufacturing group is the main culprit for Intel’s deteriorating margins and earnings. Specifically, in the past, manufacturing costs would be split among the various product groups. Instead, now these costs are solely allocated to the manufacturing group. Besides wafers, there are still some other costs for the product groups, such as wafer expedites and samples, but these too are now priced similarly as at other foundries.

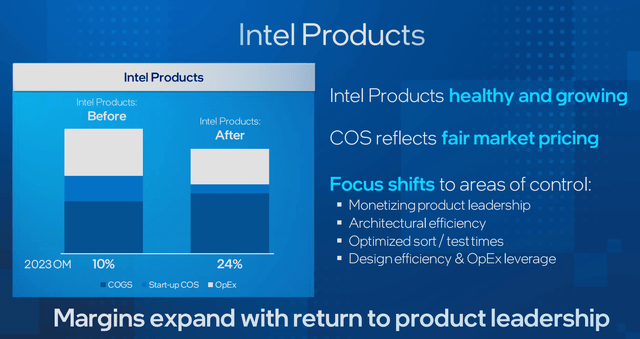

Overall, for 2023 the operating margin of the product groups (CCG-DCAI-NEX) under this model would have been 24% instead of 10%, mainly (as just discussed) due to the near-complete elimination of allocated manufacturing costs.

Hence, Intel’s product groups actually remain reasonably profitable despite the process technology issues in the last half a decade. Although, looking closer shows that it is mainly the client group that is quite profitable, with NEX and DCAI struggling much more. Of course, this is not that unexpected, as this was already to some extent visible in the prior financials, and DCAI has been most impacted by the loss of process leadership (substantial core count deficit).

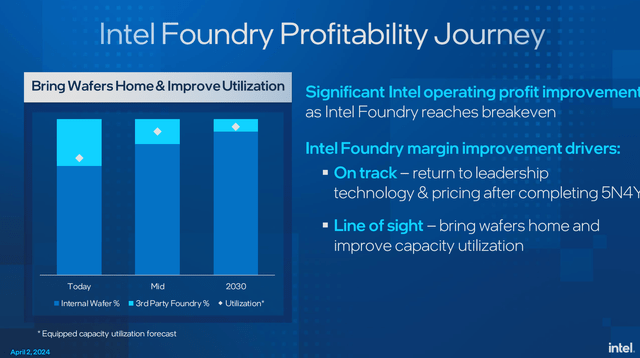

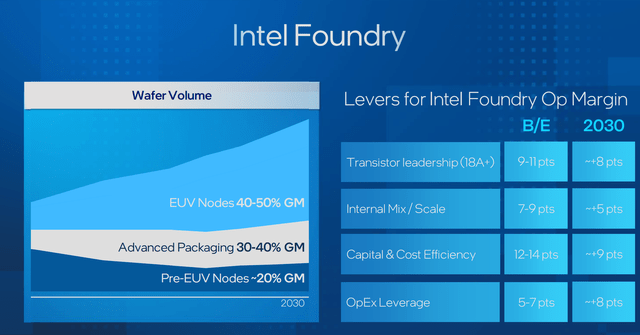

So instead, as the manufacturing costs are now solely incurred by Foundry, it shows that Foundry is operating at a stunning -37% operating margin. As has been widely reported, Foundry had a $7B operating loss in 2023 on $19B revenue. Intel expects this loss to peak this year, followed by a linear improvement towards the 2030 target of 40% gross margin and 30% operating margin.

Note that this target is a new disclosure. It is some 10+ percentage points below TSMC, perhaps reflecting some higher price aggressiveness as a new entrant and challenger, but still respectable, especially as it is roughly similar to TSMC’s results prior to COVID-19. Intel expects to reach breakeven for the manufacturing business midway during this period, so around 2027. Overall, this target represents around a 67-percentage point swing in operating margin in 6 years, which is ambitious (and indeed worthy of the term turnaround).

Looking at this from a higher level, the stock reacted to the downside on this webinar, which was quite reminiscent of when Intel first disclosed the financial implications of the turnaround in October 2021 during its earnings call at the time, after a year of mainly technological and business-related disclosures and discussions.

However, the plan Intel presented is a simple reality, and is aligned with what I have been discussing as the Intel thesis since (at least) Pat Gelsinger’s return in 2021: while the technological turnaround (5N4Y: 5 nodes in 4 years to return to industry process technology leadership) is slated to be completed by the end of the year by finishing the development of 18A, the first products are planned for the second half of 2025. Then, like pretty much all companies except the likes of Apple Inc. (AAPL) and Samsung Electronics Co., Ltd. (OTCPK:SSNLF) with their blockbuster smartphone launches, it will take another year or so until these products are really established in the marketplace (launching in various PCs and data centers, replacing old products), and hence for the manufacturing output to become more substantial.

As such, as I have been arguing for years, there is a clear distinction between the technological turnaround and the financial one. In the past, I have compared this to AMD and its Zen turnaround. Looking at the stock price shows that the launch of Zen was only the beginning of the financial implications of completing the turnaround, with the stock continuing to rise for many years thereafter. What Intel showed, with the (Foundry) operating margin (loss) bottoming in 2024 before recovering over the next half a decade or longer, is very similar if not exactly the same.

For example, when Pat Gelsinger launched IFS in early 2021, which was before the 5N4Y announcement, even if Intel had revealed its roadmap under NDA, potential customers at that time were indeed just buying into a roadmap from a company with questionable execution (at best) in the half a decade prior. At the webinar, Pat Gelsinger said it now has 50 test chips on 18A in the pipeline (and 5 customers), so progress is steadily mounting.

As confirmed during the Q&A, besides the lower revenue expectations, there really isn’t much of a change in the margin profile expectations and goals compared to the investor meeting two years ago: although the near- to mid-term might be a bit below prior expectations, the long-term goal is actually more ambitious than the 2022 investor meeting long-term model.

In the near term, by the time Foundry reaches breakeven, the overall operating margin will be around 25%. For comparison, the 2021/22 goal was to reach a 20% FCF margin by 2026. Under Bob Swan, the goal was for FCF to be 80% of net income, with net income itself being around 80% of operating income. Hence, assuming this holds, the operating margin would have to be about 31% to reach the 20% FCF target, a bit higher than the new target.

On the other hand, the new long-term goal (although one which Intel has talked about before, but without any explicit deadline) of 40% operating margin would likely result in more than 20% FCF margin. In fact, even during the heydays of milking the 14nm node from 2018-2020, the operating margin only topped out at 33%, at the high-end of Intel’s official target at the time. The new target is actually the most ambitious in Intel’s history, making the selloff a bit baffling when viewed in this light.

As such, investors should see the stock reaction as rather a reflection of the time it will take to reach this target, which is far longer than what the stock market usually tends to discount. While, as mentioned, some headlines were focusing on the $7B foundry loss, obviously this re-slicing of the financials doesn’t change those that Intel has reported over the last year (and 2024 was announced to be the year of peak loss, which is also in-line with the 2022 investor meeting).

Some investors might remember that around the 7nm delay in mid-2020, there were a lot of discussions regarding whether Intel would have to spin off/sell its uncompetitive fabs, as it seemed Intel was falling irrecoverably far behind (which the turnaround has now finally disproven).

However, as the disastrous foundry P&L shows, this actually doesn’t seem possible without Intel Foundry sooner or later going bankrupt. Either Foundry tries to optimize costs like stopping node development like GLOBALFOUNDRIES Inc. (GFS), but then rather soon it would lose the Intel manufacturing business to TSMC as Intel Products seeks to remain competitive by buying leading-edge wafers. So it would have fabs, but no customers.

Alternatively, if Foundry had operated as it has in the last few years (investing in the expensive turnaround), then it too would have gone bankrupt, as shown by those multibillion-dollar (“$7B”) losses visible in the Foundry P&L. Hence, as a standalone company, Foundry simply would not (have) be(en) able to fund the turnaround.

Put differently, what this effectively means is that the product groups have and are subsidizing (paying for) the turnaround. In other words, instead of the “margin stacking” theory of why an IDM is superior to a fabless company, Intel is currently experiencing “margin subtraction” from its highly unprofitable, trailing edge manufacturing business.

To be sure, some might note or argue that all this is simply financial engineering trickery, as Intel could vastly change the P&L of both groups depending on the wafer price it (arbitrarily sets) for those internal wafers. Of course, the P&L of both groups would be correlated as the overall Intel P&L cannot change, but the idea is that Foundry could have been made to look a lot more profitable by setting a higher wafer price that Products would have to pay.

However, while technically correct, in practice this is wrong, or at least against the whole idea of the model (being a realistic model). As the Product groups are free to choose any foundry for their designs, if the Foundry raised its prices, it would be uncompetitive against wafers of competitive foundries, so Products would switch foundries. Foundry has to charge market prices.

Note that this switching has already happened to some extent over the last few years (and will continue for the next year with Arrow and Lunar Lake), with Intel increasing its outsourcing. This is yet another reason (or confirms the aforementioned one) why Intel Foundry wouldn’t (have) survive(d) as a standalone business, as outsourcing has increased from around 20-25% to 30%. At least, it is also one of the reasons for the decline in Foundry’s revenue and profitability. Given the meager profitability of 10nm, it might be beneficial to leverage foundries instead (even for chiplets on the same node, i.e., using N6 instead of 10nm/I7).

This is indeed what Intel seems to have done, with some Meteor/Arrow/Lunar Lake tiles being built by TSMC (although for the GPU tile, one might argue that this was done because Intel 4 does not have a higher-density library that the GPU would use, which was done to speed up Intel 4 development). Going forward, Intel has said that its goal is to reduce its reliance on foundries, and from the graph in the presentation, it seems the target is even below the amount it was doing prior to Pat Gelsinger (i.e., far below 20%).

In any case, as the reported P&L shows, a standalone Intel Foundry would have seen a large decrease in volume/revenue and a further increase in. This would only be exacerbated if it had raised prices. So, in the model, Intel is using wafer prices conforming to those of similar nodes from competitors. Either way, going forward Intel Products will simply be charged the same price as any other Foundry customer. Hence, this model is indeed a valid and real representation of the underlying foundry economics.

Cost reductions

Since, as discussed, Foundry is currently not profitable, being a trailing edge IDM is indeed a net drag on the company currently. The margin stacking will only occur and become a reality when Foundry becomes profitable. The only way for Foundry to become profitable (in a real way, not by arbitrarily charging unrealistically high, uncompetitive wafer prices) is by regaining process (cost-density) leadership and achieving high yield.

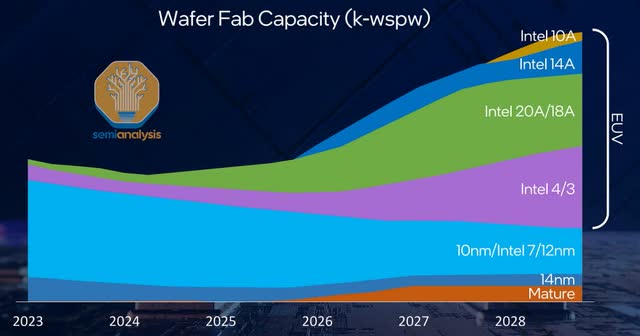

Of course, as mentioned in the introduction, this model ultimately does not change the underlying economics, as those dynamics are ultimately just a function of regaining process leadership. Nevertheless, one point that is amplifying the turnaround is EUV, which Intel referred to as the “EUV wall,” and mentioned a cost per transistor delta of 2x. As a reminder, due to EUV less multiple patterning steps are required. So, while the tool is much more expensive, ultimately the reduced process flow makes up for that.

Hence, the combination of EUV introduction and the accelerated 5N4Y cadence (moving quickly past Intel 4/3 to the second-gen 20/18A shrink) should make for a very large improvement in cost structure and economics. Again, though, it will take several years for these nodes to become a majority in terms of volume.

In addition, with Foundry now being tasked with becoming as efficient as possible as a standalone business, it turns out (as Intel had discussed previously already as part of its $8-10B spending reduction plan) there are some hidden costs/inefficiencies in the business. For example, for Intel wafer expedites are/were very common compared to the foundry space, where those kinds of wafers are very expensive. In practice/essence, this results in lower utilization, so several billion dollars can be saved simply by improving utilization to best-in-class levels (i.e. phasing out expedites by charging appropriate costs to customers, conforming to standard market practices).

Doing the math, reducing costs by several billion from such efficiencies would indeed be a large contributor towards (and beyond) breakeven. As shown above, the three other ones are transistor leadership, scale (including from insourcing outsourced products/chiplets), and opex leverage. Regarding insourcing, Pat Gelsinger said two whole fab modules worth of wafer capacity would be brought back. From the graph, it seems outsourcing will be reduced from around 30% to 10%.

Process comparison

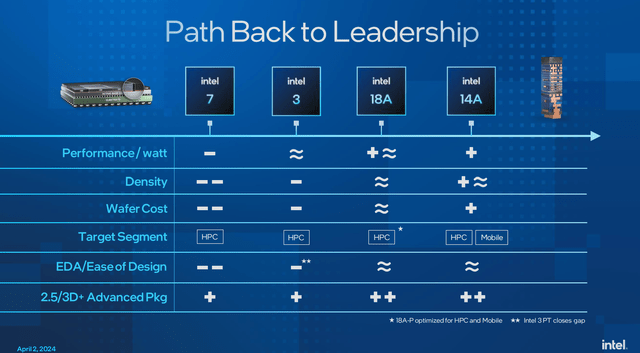

Pat Gelsinger also provided a qualitative overview of Intel’s process node benchmarking, showing that it expects to only further extend its regained leadership with 14A.

It wasn’t mentioned if this comparison is based on what is available at the point of node introduction into the market or based on the same name. For example, clearly, Intel 7 was compared against TSMC N5, as I7 has a higher density than N7. However, during the presentation, Pat Gelsinger said 14A would be both earlier to market and also superior in power, performance, area, and cost, which (the time to market part) implies it is compared against A14. So it isn’t sure if 18A is compared to N3(P) or N2, but presumably N2.

Either way, the density comparison is actually a bit surprising. Intel 3 should already be quite close to N3, and presumably, 18A represents a full-node shrink (2x). As TSMC is hardly scaling at N2, 18A should be meaningfully denser than both nodes, i.e., more than just a wavy sign.

Risks

While, as discussed, all the fundamentals for the turnaround are in place, the main “risk” is that the 2030 target for 60/40 gross and operating margin might be too ambitious, especially the operating margin target, as Intel only achieved about 33% OM at its highest point.

More in general, while the line of sight in terms of modelling towards these goals should be straightforward, it still needs to be executed. In any case, while those operating margin targets are encouraging, one of the main drivers for investor returns (in any stock) is revenue growth, which Intel has so far not demonstrated. Intel did state $15B in annual external foundry revenue as its 2030 target.

Investor Takeaway

Ultimately, having a separate P&L for both foundry and products is very logical and perhaps could or should have been done years or decades ago already. Specifically, doing this exercise has uncovered multiple inefficiencies in the manufacturing organization that will likely save multiple billions of dollars. This is not different from (i.e., it is part of) the $8-10B cost reduction plan that was announced in the wake of the downturn, which at the time was cheered on by investors.

In addition, the technological turnaround also remains just as valid, with 18A completing development by the end of the year, ramping in 2025 and starting to hit the P&L more meaningfully in 2026. More broadly, by quickly advancing through two full process nodes (and two further intra-nodes) over the course of 2024-25, regaining process leadership, and which also coincides with the very important introduction of EUV, Intel’s inherent cost structure should improve dramatically.

Nevertheless, even when Foundry is projected to breakeven by around 2027, the EUV nodes collectively still will not represent even half of Intel’s wafer volume, although quite a large portion of the pre-EUV capacity is due to advanced packaging. In the grand scheme, though, EUV output to reach nearly 50% of overall volume within three years is quite solid.

Overall, one of the main takeaways from the webinar and Foundry P&L update specifically should be that Intel expects Foundry to become profitable as a foundry – both internally and externally. When Intel first announced Foundry (called IFS at the time), there were some questions regarding its potential profitability, and those have now been answered given the 40/30 GM/OM target. This represents a 67-point improvement from 2023, which is indeed poised to mark a monumental turnaround. To that end, Intel has simply laid out a realistic and multi-pronged strategy to turn its manufacturing business around, of which regaining process leadership is just the start of the financial turnaround, and not the end.

The stock sold off after the webinar. This was unfounded, as the overall strategy and profitability targets are unchanged. It seems hearing some of the specific numbers or the time it will take, instead of just directional comments, spooked some investors. Nevertheless, Intel’s goal of achieving (up to) 40% operating margin is actually a full 7 points higher than during its heydays of profitability from the last decade, so it is not sure what investors are complaining about. It is not as if there won’t be any improvements before 2030. In fact, the improvement in both Foundry and overall P&L should be quite linear through the period, which really shouldn’t be surprising given that one just does not convert a whole factory network (representing on the order of $20B in foundry revenue) to those new turnaround nodes, and new products take at least a year to ramp into the market as well.

Nevertheless, if Intel achieves the high-end of its midpoint profitability target, then it will already be back to within a few points of its historical profitability performance by 2027, which is “just” two years after introducing the first two turnaround products (Clearwater Forest and Panther Lake in H2’25), and roughly in-line with the investor meeting plan from two years ago, where 2022-24 was marked as the investment period with low profitability, which indeed remains the case as well.

If anything, the webinar should have solidified long-term investors’ confidence in the long-term turnaround and investment case, as that is exactly the plan Intel laid out in detail. Similar to AMD with Zen in 2017, 2025 should mark the start of a new era of Intel monetizing the industry-leading assets it is currently finishing development of, as well as potentially further extending its leadership with follow-up nodes such as 14A (cf. Zen 2+). Both should reinforce each other (as shown in the webinar), driving investor returns for many more years.

Editor’s Note: This article discusses one or more securities that do not trade on a major U.S. exchange. Please be aware of the risks associated with these stocks.

Analyst’s Disclosure: I/we have a beneficial long position in the shares of INTC either through stock ownership, options, or other derivatives. I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it (other than from Seeking Alpha). I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.

Seeking Alpha’s Disclosure: Past performance is no guarantee of future results. No recommendation or advice is being given as to whether any investment is suitable for a particular investor. Any views or opinions expressed above may not reflect those of Seeking Alpha as a whole. Seeking Alpha is not a licensed securities dealer, broker or US investment adviser or investment bank. Our analysts are third party authors that include both professional investors and individual investors who may not be licensed or certified by any institute or regulatory body.