Summary:

- Netflix’s economics have declined over the last few years in response to increasing competition.

- The deteriorating supply-side economics have killed its ability to raise prices.

- Its peers are better resourced and are able to draw on profitable ecosystems to fund their streaming services.

- Netflix faces a value dilemma and must choose between growth and profitability and management has so far chosen to chase growth, at the expense of growing value.

Wachiwit

Netflix, Inc. (NASDAQ:NFLX) has fallen from the heights of the pre-pandemic era, and entered an era of secular stock market decline. That decline in stock market performance reflects a long-standing erosion in the competitive advantages of the business. As the supply-side gets worse, the company’s ability to raise prices and boost its profitability decline. Netflix faces a value dilemma and must choose between growth and profitability. It cannot have both. Management seems determined to chase growth, and with that, investors should expect a steep decline in the value of the business.

The Stock Has Fallen from Its Highs

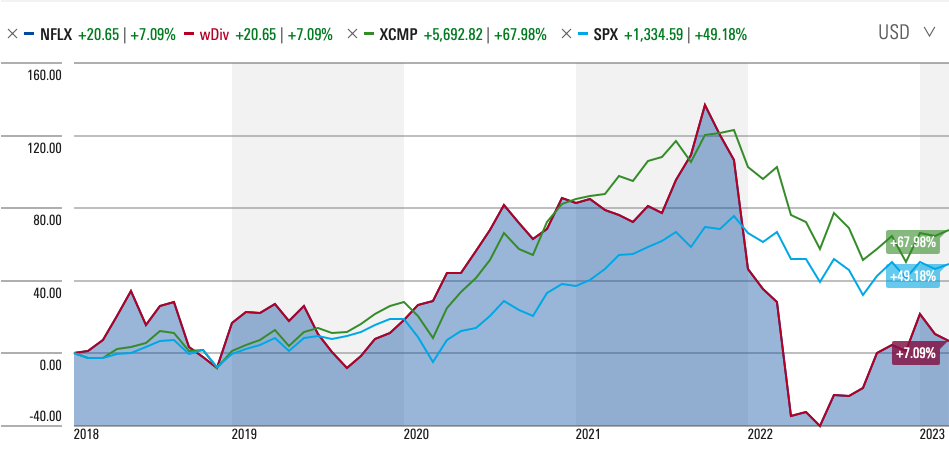

In 2019, Netflix was named the best investment of the decade, earning investors a 4,000% return in that time. Yet, in the last five years, the total return to shareholders has been just over 7%, compared to nearly 50% for the S&P 500 (SPX), and nearly 68% for the NASDAQ Composite Total Return Index (XCMP). Netflix, once a stock market darling, has fallen from its highs.

Source: Morningstar

Long-term investors in the stock have fallen into a wide-spread investor error. Many investors, attracted by Warren Buffett’s philosophy, have come to believe that long-term investing is grown-up investing. However, research shows that 96% of stocks, if held across their lifetime, do not outperform Treasury bills. Indeed, even Warren Buffett does not hold all his stocks for the long-term. One of the key reasons why stocks tend toward the same rates of return as Treasury bills is that competitive advantages, and therefore returns on invested capital (ROIC), decline over time. The business that resists this gravitational pull is rare. Netflix is not one of them. Driving Netflix’ decline has been a steady erosion of the business’ competitive advantages, an erosion that investors ignored for many years.

Deteriorating Financial Performance

In this five year window, revenue has declined from $15.79 billion in 2018 to $31.62 billion in 2022, at a 5-year compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 14.9%. According to Crédit Suisse’s “The Base Rate Book”, in the 1950-2015 reference period, 12.6% of firms achieved a similar rate of growth over a 5-year period. Only 14.5% of businesses ever achieve a superior rate of growth. The mean 5-year revenue CAGR is 6.9% and the median is 5.2%. (While the reference period is outside our analysis period, it serves as a reference point to judge Netflix’ results, given that there is some persistence in the tendency of those results.)

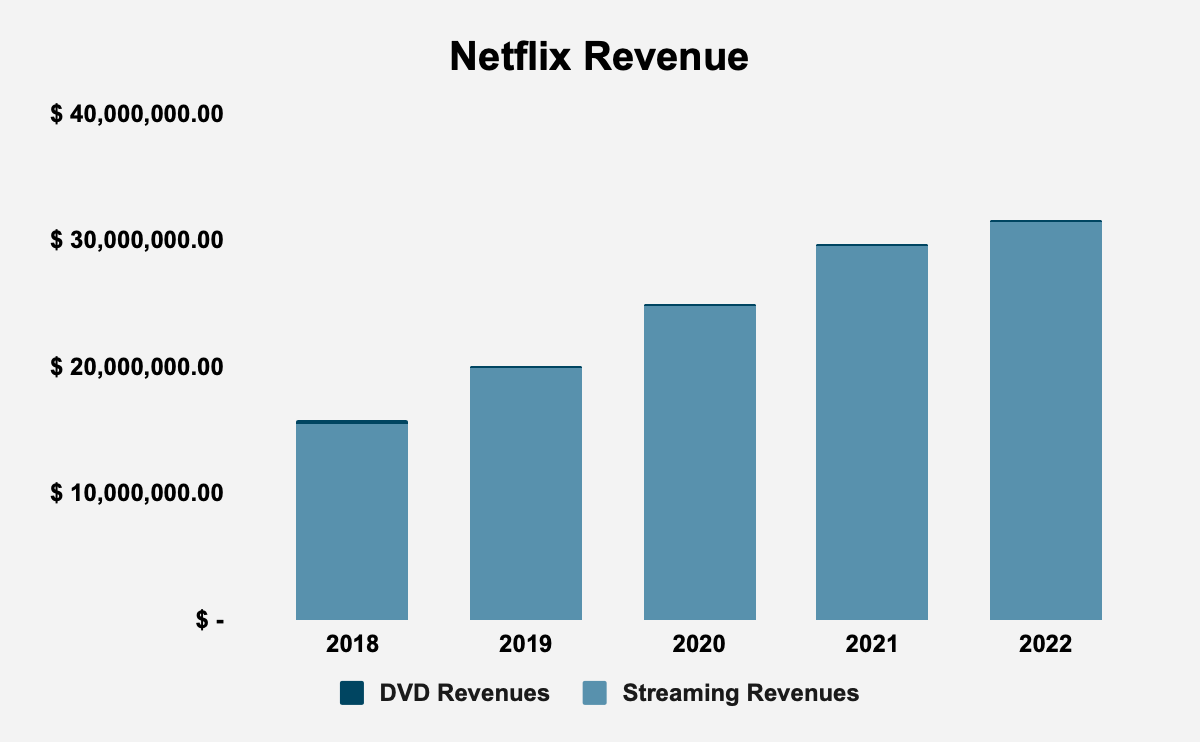

Today, Netflix operates as one operating segment, and revenues emanate largely from membership fees related to the provision of streaming services. There are different streaming membership plans, each with its own unique pricing, ranging, in the United States, from $1 to $26 per month. Members are billed at the beginning of the month and revenues are recognized ratably over each month. Netflix still derives a residual revenue from the sale of DVDs. In 2022, streaming revenues were 99.4%of total revenue.

Source: Netflix, Inc. Filings and Author Calculations

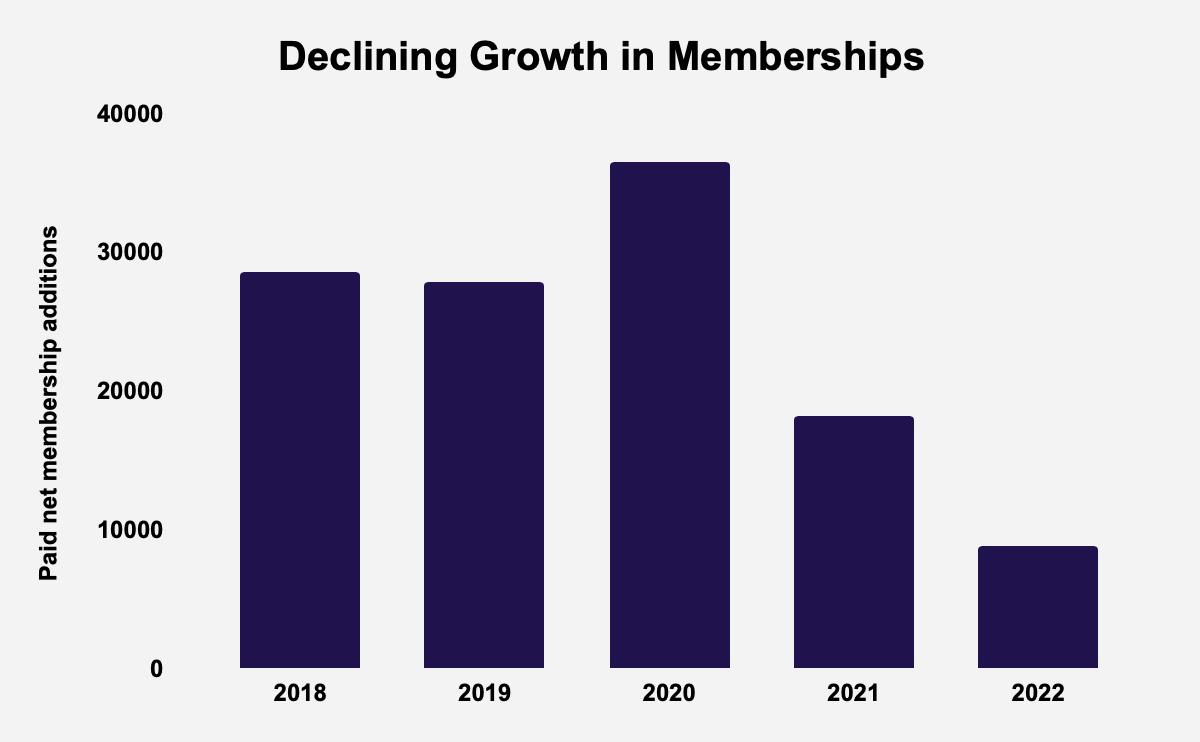

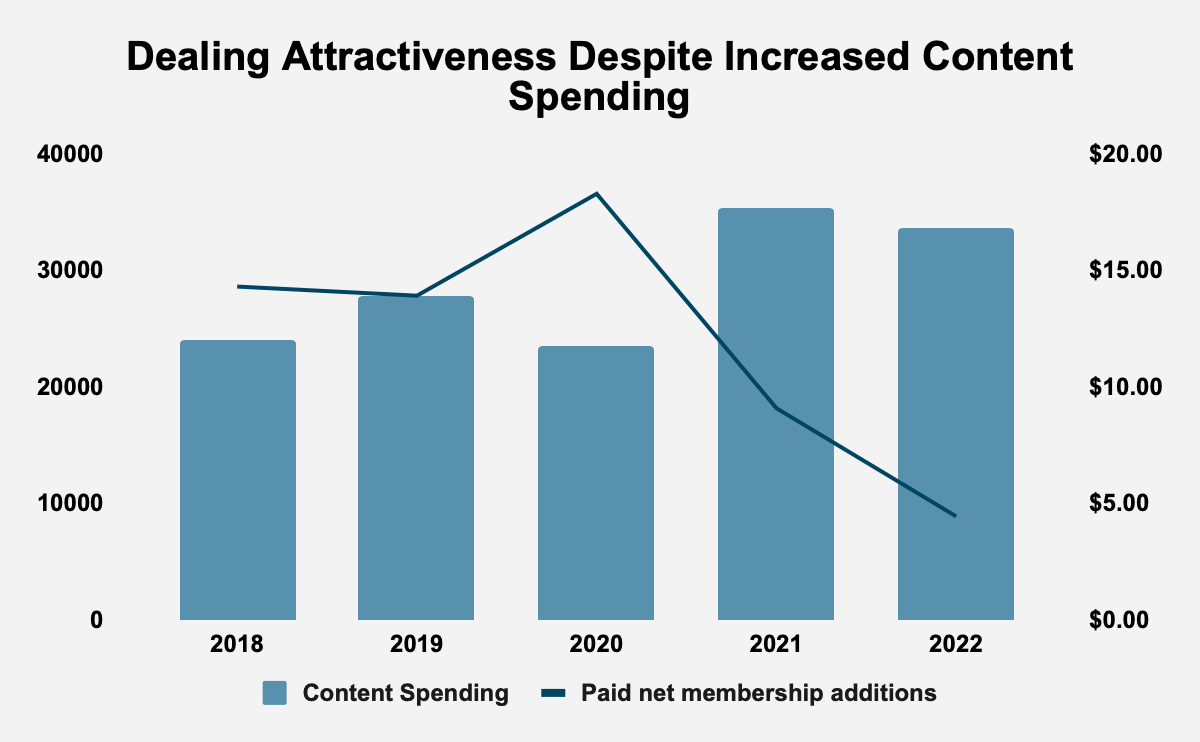

The number of average paying memberships has risen from 139.26 million in 2018 to 222.92 million in 2022, at a 5-year CAGR of 9.87%. Although the membership is growing, growth has slowed in recent years, with paid net membership additions declining from 28.6 million in 2018 to 8.9 million in 2022, at a 5-year CAGR of -20.82%.

Source: Netflix, Inc. Filings and Author Calculations

Gross profits have risen from $5.83 billion in 2018, to $12.45 billion in 2022, at a 5-year CAGR of 16.39%. Gross margins rose from 36.89% in 2018 to 39.37% in 2022. Gross profitability (gross profits/total assets) rose from 0.22 in 2018 to 0.26 in 2019. This is still short of the 0.33 threshold that Robert Novy-Marx’ research found was an attractive level of profitability.

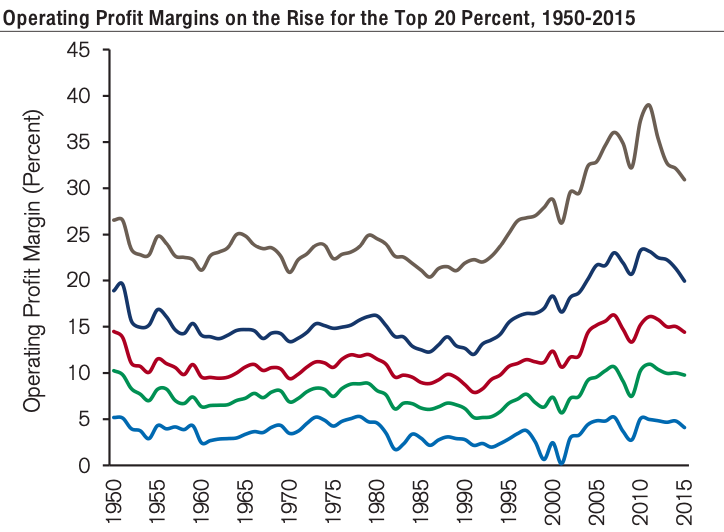

Operating income has risen from $1.6 billion in 2018 to $5.6 billion in 2022, at a 5-year CAGR of 28.54%. Operating margins have risen from 10.16% in 2018 to 17.82% in 2022. This is certainly higher than the mean operating margin in consumer discretionary, which is 8.2%, or the median, which is 8%, however, it is far lower than the top quintile operating margin for all businesses.

Source: Crédit Suisse

Net income has risen from $1.2 billion in 2018 to $4.5 billion in 2022, at a 5-year CAGR of 29.97%, a result matched by just 8.8% of firms, with only 7.5% of businesses enjoying a higher rate of earnings growth over a 5-year period. The mean 5-year earnings CAGR is 7.3% and the median is 5.9%.

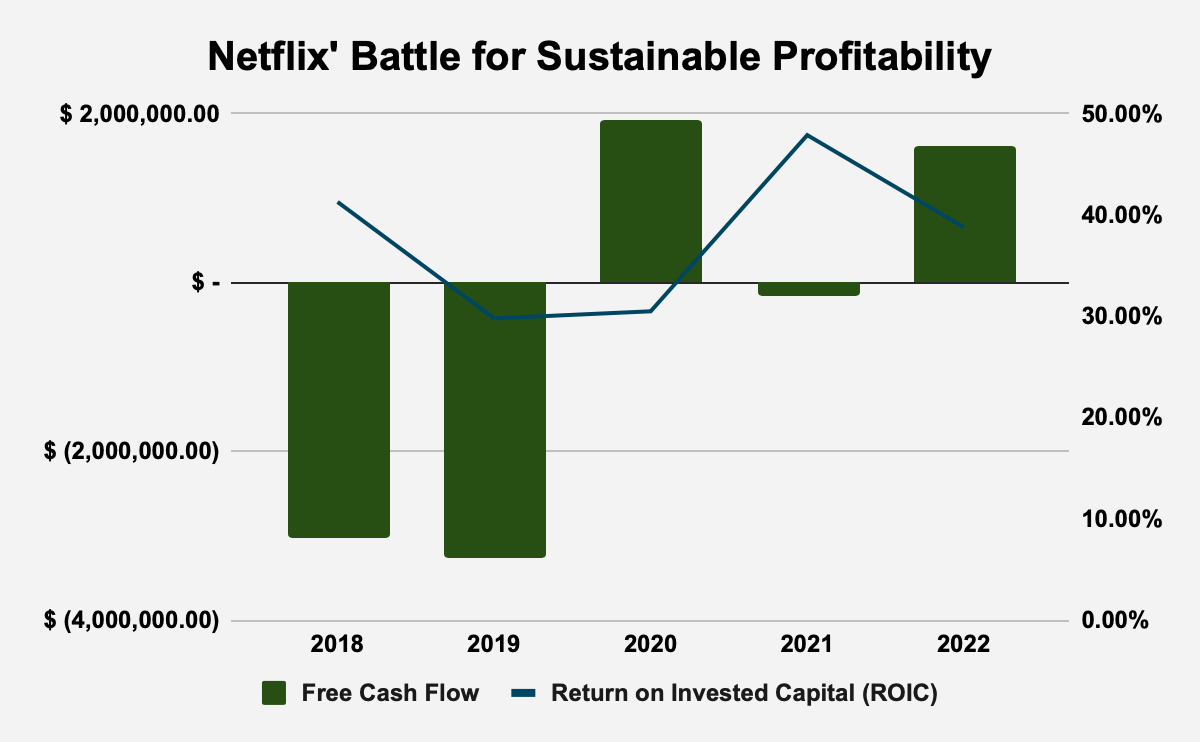

Free cash flow (FCF) rose from -$3 billion in 2018 to $1.62 billion. ROIC, meanwhile, has declined from 41.3% in 2018 to 38.8% in 2022. Over the last five years, the company has struggled to sustainably generate FCF. Indeed, the net FCF generation during that period was -$2.9 billion. If a business’ value is the sum of the present value of its future cash flows, Netflix has gone backwards in the last five years, in terms of growing corporate value.

Source: Netflix, Inc. Filings and Author Calculations

It’s Supply, Stupid

There are not many truths that are axiomatic in finance, but one of those truths is that an increase in the supply of a thing reduces the price of that thing. It is very difficult to forecast demand, and investors and managers tend to overestimate demand. Supply is easier to forecast and to analyse and a lot can be concluded without ever bothering with supply. Though there are certainly instances where supply rises and prices rise as well, these are not as common as investors and managers would like. The principal problem both investors and managers face is that supply-side decisions are taken with some distance from the prices that will be observed when the effects of those supply decisions are taken. So, for instance, a decision to buy a catalog of content in the belief that demand the following year when that content will be released, will be at a certain level, carries with it some uncertainty: that forecasted level of demand may be much lower than the range of outcomes forecast. Growth industries are especially prone to these errors. Or, more correctly, it is beneficial for a declining industry to underestimate future demand, but it is harmful in a growing industry to overestimate future demand. In growing industries, the incentives and biases are there to overestimate future demand, whereas in declining industries, the incentives and biases are there to underestimate future demand.

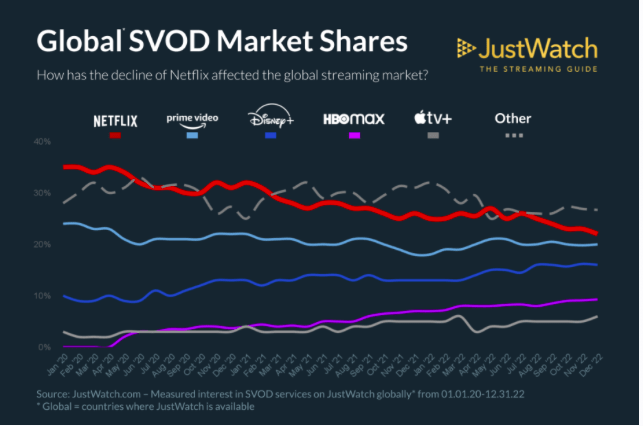

While Netflix may once have been the true king of streaming, that title is no longer theirs. In fact, the market has become so competitive that Netflix’ ability to raise prices has deteriorated in the face of competition from other streaming services. With over 15 streaming services with at least 10 million subscribers, people have more choice than at any point in the history of television. Among these competitors are Amazon (AMZN), Apple (AAPL), Disney (DIS), HBO Max (WBD), Paramount (PARA), and YouTube (GOOGL), each of whom is part of a profitable ecosystem that can fund the streaming services. Netflix, on the other hand, is a pure-play streaming service with no meaningful income from another revenue stream that could support the streaming business. Its only non-streaming revenue comes from the declining DVD-by-mail market. Secondly, these competitors all have rich catalogs of content that they own, whereas Netflix licenses much of its content, although management has tried to rectify this.

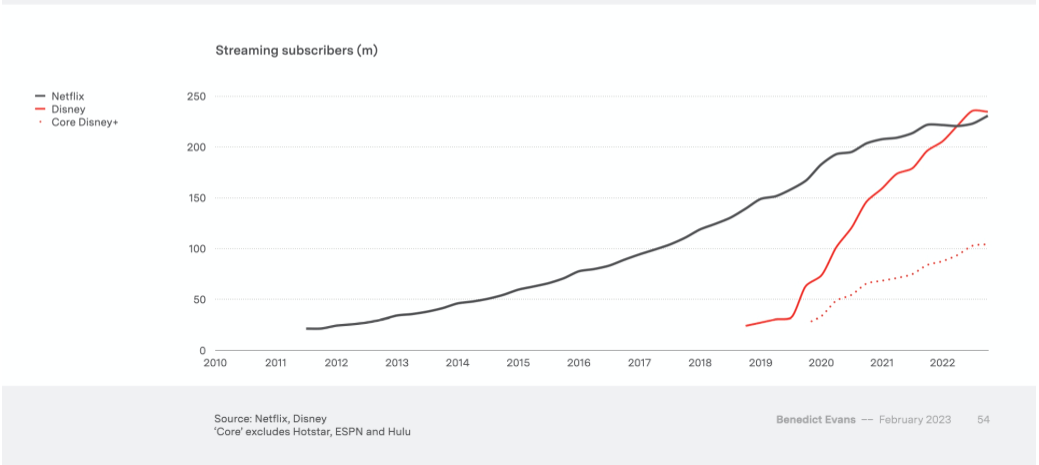

Disney, for example, has already caught up to, and passed Netflix, for the number of streaming subscribers.

Source: Ben Evans

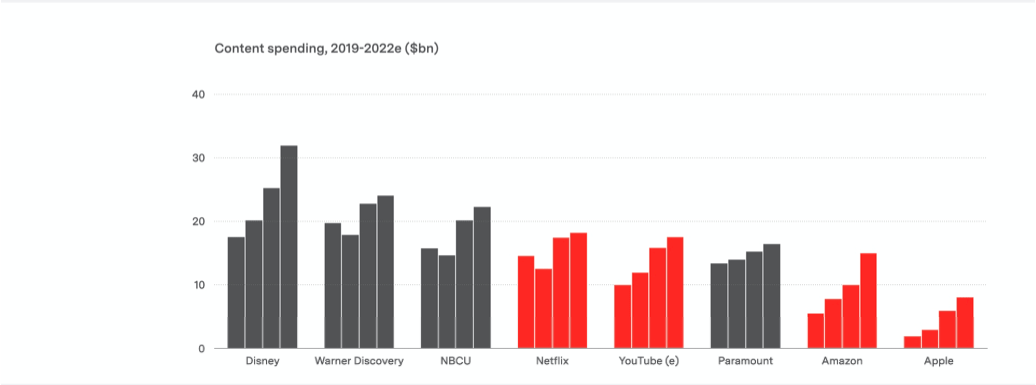

Furthermore, Disney’s content spending already exceeds that of Netflix in the last three years, reflecting how Disney is able to dip into its profitable core business to fund its streaming business.

Source: Ben Evans

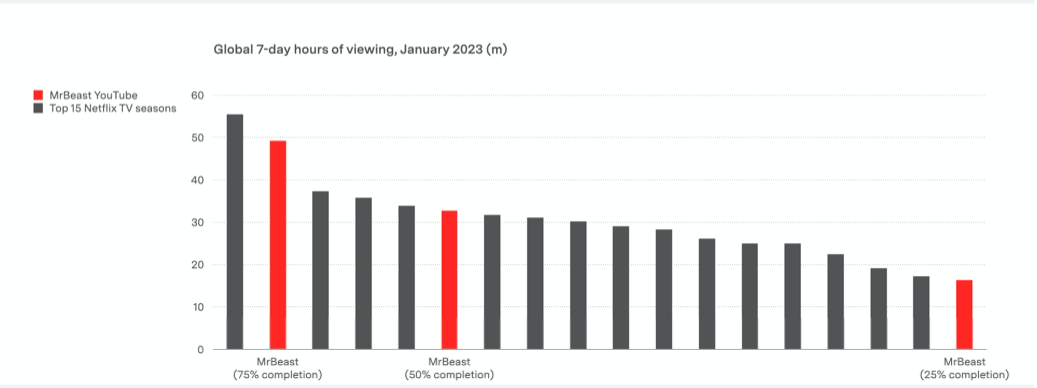

YouTube is particularly fascinating and an example of how Netflix’ competitive advantages have been greatly exaggerated. YouTube’s creator payouts match those of TV production budgets, and the platform’s share of U.S. TV viewing already exceeds that of Netflix. While Netflix has often been hailed as disrupting TV, the truth is that YouTube is more disruptive of TV than Netflix is. An example of this is the show, MrBeast, whose viewing numbers compare favorably with those of a top 10 Netflix show.

Source: Ben Evans

Netflix’ success and an evident desire for streaming content, has had the adverse effect of attracting competitors who are larger, wealthier, and have learned all the lessons that Netflix has had to teach. Rather than being a disruptor, Netflix is a declining incumbent.

Netflix already charges the highest price for its streaming services, and with competition so fierce, it is hard to see how they can raise prices any further. Think about the biggest shows of the last decade, such as Game of Thrones, or even the derided Lord of the Rings: The Ring of Power, and, it is arguable that Netflix has not produced a single show that can contend for the title of the “best”, or most watched. Even if they can, the fact that other services can offer comparable or even superior content has reduced Netflix’ pricing power quite significantly.

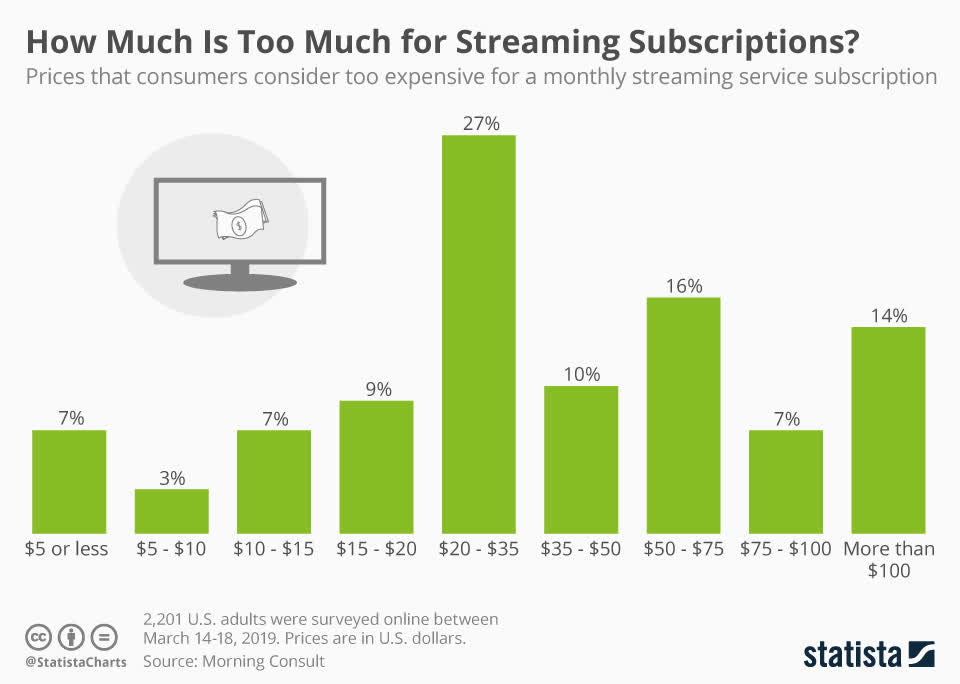

Source: Statista

Furthermore, there is some evidence that Netflix’ pricing is the limit to which a streaming service can go in terms of pricing. How many subscribers would tolerate a $5 increase in the price of the premium service, for instance? Answering such basic questions reveals the extent to which Netflix’ competitive advantages have eroded. There is less and less of a reason to be on Netflix, and those reasons decline with each day. Previous attempts to raise prices have not fared well, and it is unsurprising that the company has mulled an ad-model for this business.

Source: Statista

Most people think ads suck, and Reed Hastings has said as much, so the idea that the company will be forced into an ad-model is a signal of how bad things are at Netflix.

We saw that Netflix has burnt through $2.9 billion in cash over the last five years, and this is really the price of being a pure-play streaming service.

Netflix’ problems come into further focus when we consider that despite increasing spending on content from $12.04 billion in 2018 to $16.84 billion in 2022, its ability to add new members has declined.

Source: Netflix, Inc. Filings and Author Calculations

This all adds up to a weakening market share, with Netflix losing 13% of its market share between 2019 and 2022.

Source: NASDAQ

In an increasingly competitive market, Netflix simply cannot raise prices significantly, or grow profitably, rather, management has to play defense and focus on ROIC, a decision that it does not seem to have contemplated.

Netflix’ Value Dilemma

The distinction between value and growth investing is superficial. As Warren Buffett once remarked, “Growth is always a component in the calculation of value, constituting a variable whose importance can range from negligible to enormous and whose impact can be negative as well as positive.” Netflix is at the point where growth is a minus, and now, it has to choose between growth and improving ROIC. The company is incapable of generating FCF without slashing content spending, and yet seems incapable of accepting its fate as a declining business that should be playing defense. Growth is, in any event, largely unsustainable for most businesses, and certainly, Netflix’ growth is slowing down. In fact, the pursuit of growth is destroying value, rather than creating it. Accepting realities will be beneficial for shareholders, given that a 1% increase in ROIC creates more value than a 1% increase in revenue.

Netflix Overstates the Longevity of its Content

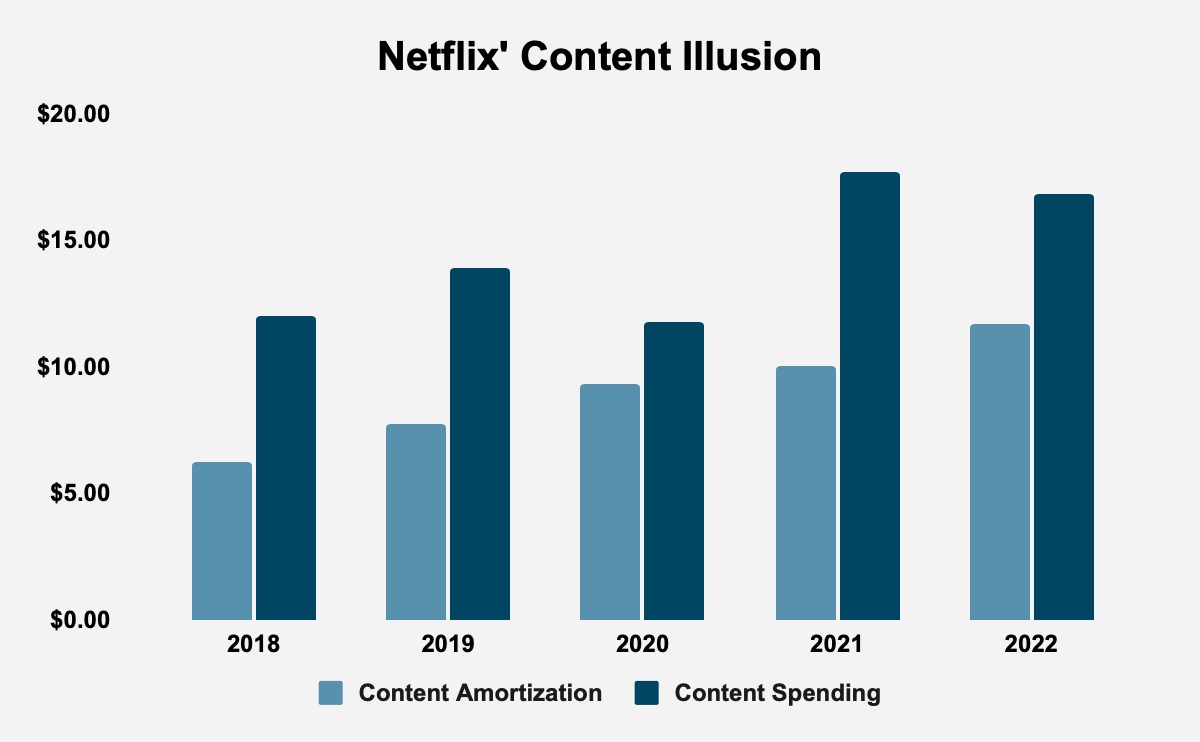

The majority of the company’s cost of revenues are made up of content amortization. As Stephen Clapham has pointed out, Netflix has aggressively increased the content amortization period of its content as the economics of the business has deteriorated. This is significant because Netflix’ content amortization periods exaggerate the longevity of their content in order to improve the firm’s reported financial performance.

Source: Netflix, Inc. Filings and Author Calculations

Indeed, in the auditor’s report, Ernst & Young once again raised the company’s content amortization policy as a “critical audit matter”, saying:

As disclosed in Note 1 to the consolidated financial statements “Organization and Summary of Significant Accounting Policies”, the Company acquires, licenses, and produces content, including original programming (“Content”). The Company amortizes Content based on factors including historical and estimated viewing patterns.

Auditing the amortization of the Company’s Content is complex and subjective due to the judgmental nature of amortization which is based on an estimate of future viewing patterns. Estimated viewing patterns are based on historical and forecasted viewing. If actual viewing patterns differ from these estimates, the pattern and/or period of amortization would be changed and could affect the timing of recognition of content amortization.

We obtained an understanding, evaluated the design and tested the operating effectiveness of controls over the content amortization process. For example, we tested controls over management’s review of the content amortization method and the significant assumptions, including the historical and forecasted viewing hour consumption, used to develop estimated viewing patterns. We also tested management’s controls to determine that the data used in the model was complete and accurate.

To test content amortization, our audit procedures included, among others, evaluating the content amortization method, testing the significant assumptions used to develop the estimated viewing patterns and testing the completeness and accuracy of the underlying data. For example, we assessed management’s assumptions by comparing them to current viewing trends and current operating information including comparing previous estimates of viewing patterns to actual results. We also performed sensitivity analyses to evaluate the potential changes in the content amortization recorded that could result from changes in the assumptions.

The content amortization policy is, to my mind, concerning because it is hard to imagine that a significant part of Netflix’ catalog has a life cycle of more than a year. Yet, in the company’s most recent “Overview of Content Accounting”, says that 90% of its content is fully amortized within four years, after its first month of availability, with a maximum amortization period of 10 years. Clapham argues that Netflix’ actual amortization period is around 6 years. I will not go into those claims, but will ask a different question: how many times do you watch Netflix content that is older than one year? Amortizing the content over 4 years, let alone 6 years, seems quite optimistic.

While Netflix is not doing anything illegal, the issue does point to the weaknesses of the business model and of the accounting standards at play.

Valuation

Netflix has a price/earnings (P/E) multiple of 31.36 compared to a P/E multiple of 21.45 for the S&P 500. With an enterprise value of $147.26 billion, the firm has an FCF yield of 1.1%, compared to an FCF yield of 1.8% for the 2000 largest firms in the United States, according to New Constructs. In other words, the company is valued higher than the market, while its FCF are trading at a lower yield. For anyone who has read this far, the company’s economics are in secular decline and are more likely to match the returns of Treasury bills, rather than beat the market. This suggests that further declines in the market value of the business are to be expected.

Conclusion

Netflix is in secular decline. The reason is fairly simple: competition has increased and is getting harsher and harsher. The company faces better resourced companies, who can outspend it, and in the case of Disney and YouTube, match or exceed its numbers, and who are able to function without as much concern for profits. The days of pure-play streaming services are over. Competition is too intense for businesses that depend entirely on streaming. In that light, investors should expect further erosion in the value of the company, until management wakes up to the impossibility of chasing growth and being profitable.

Disclosure: I/we have no stock, option or similar derivative position in any of the companies mentioned, and no plans to initiate any such positions within the next 72 hours. I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it (other than from Seeking Alpha). I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.