Summary:

- Nvidia’s TAM is projected at $2 trillion, with a conservative market cap estimate of $8T in 10 years, presenting limited downside risk for long-term shareholders.

- A bear case assumes 50% market share and 50% margin, while a bull case assumes 90% market share and 78% margin, leading to a $54T market cap in ten years.

- Key risks include a severe recession resetting client spend, loss of CEO Jensen Huang, and competition from AMD, Intel, and start-ups like Groq and Etched.

- Despite risks, Nvidia’s strong moat and AI-driven chip advancements suggest a strong buy with huge upside potential and limited downside.

Editor’s note: Seeking Alpha is proud to welcome Michael B Howard as a new contributing analyst. You can become one too! Share your best investment idea by submitting your article for review to our editors. Get published, earn money, and unlock exclusive SA Premium access. Click here to find out more »

Sundry Photography

Nvidia’s (NASDAQ:NVDA) CEO Jensen Huang has stated one trillion USD worth of current data centers need to be transitioned to accelerated computing immediately. He has also indicated that Nvidia’s Tangible Addressable Market (TAM) growth will be one trillion USD. Together, he calls this a two trillion dollar revenue opportunity (a reminder that trailing twelve-month revenues are 96 billion USD). Executing some thinking and basic math on market, market share, margins and multiples gives us a conservative market capitalization of 8T in ten years, which I consider my bear case. I will also execute the bull case, which you will find at the end of the article.

Tangible Addressable Market

Nvidia’s CEO Jensen Huang has stated in numerous talks (see minute mark 35:39) that there is two trillion USD worth of TAM in data centers that will require replacement. Jensen has stated that one trillion is required immediately, and another trillion over the next four to six years as the TAM grows.

Bear Case (1.6 Trillion over ten years)

Let’s say the TAM is not that high – our bear case will be 800 billion USD, with another 800 billion USD in growth over the next years. CEOs are known for exaggerating their TAMs.

Bull Case (2.2 Trillion over ten years)

Jensen himself is someone who practices under-promising and over-delivering. This is evident by his constant top- and bottom-line beats on earnings reports over the past several years. If Jensen is being conservative as well with his estimation of Nvidia’s TAM, it could be 10% higher than his estimate, hence 2.2 trillion USD.

It should also be noted that within just a few years, even the Blackwell chips will need to be replaced. Remember that Nvidia has changed its innovation and production schedule from a new chip series every two years, to a new chip series every year. That means the best compute upgrades happen every year for clients such as hyperscalers and other large companies that can afford them.

In short, that means that even though there is as much as 2.2 trillion USD worth of compute to be updated in the coming few years, that compute will also need to be changed again, in as little as a few years to every year – again, for the companies that can afford it.

Market Share

The general consensus among AI industry leaders (Johnathon Ross, for example), is that if computing doesn’t experience any more revolutionary leaps forward in the medium term (like Ross is trying to do with his company Groq, circumventing Nvidia’s accelerated computing chain of proprietary technologies entirely), that the market is now “a lock” for Nvidia in terms of GPU sales and accelerated computing share. That market share for Nvidia is currently 88%.

According to Tom’s Hardware, AMD’s MI300X chip was slated as the direct competition to the H100 and is more advanced in a variety of ways, including cache bandwidth, latency and inference. One would think this gives AMD the advantage, but timing is the issue. The H100 came out nine months before the MI300x, meaning the H100 was the best in the field for that period. Further, Blackwell is designed to be backward-integrated, meaning any computational work done on H100s is compatible with forward chips, including the Blackwell series.

Timing is better on AMD chips going forward: AMD’s MI325X, the successor of the MI300X, is scheduled for release next month. This is within a month or so of the release of the first Blackwell chips, so comparative loss in computational advantage for clients is minimal in that short timeframe. The problem for AMD now is that the MI325X is not even close to the highest tier GB200 using two GPUs from Nvidia. This is not to say that large companies are not buying AMD chips:

“The AMD Instinct MI300X accelerators continue their strong adoption from numerous partners and customers, including Microsoft Azure, Meta, Dell Technologies, HPE, Lenovo, and others, a direct result of the AMD Instinct MI300X accelerator exceptional performance and value proposition,” said Brad McCredie, corporate vice president, Data Center Accelerated Compute, AMD.

Going forward, it is uncertain exactly how the market share will be divided. But we know that MI325X doesn’t stack up against the GB200 series chip. AMD also doesn’t have the volume of sales to keep up with Nvidia’s sales volume growth.

Bear Case (Market Share of 50%)

Analysts have pretty much expected, for years now, that Nvidia’s market share in chips will deteriorate over the medium term. Let’s assume that’s true: that AMD’s MI350X and MI400X chips wear down the Blackwell series’ market share, giving AMD the capital and compute required to write a credible alternative to Nvidia’s Rubin series (the series after Blackwell).

We’ll suggest that in ten years Nvidia’s accelerated computing market share is only 50%. I want to note as an aside that Nvidia has other forms of revenue (gaming, auto, cloud, etc.), and that for each GPU sold, there are ongoing services attached for installation (at 37,000 per month per Nvidia expert) and AI software to actually run the GPUs which costs 4,500 per GPU per year which could have strong pricing power over time as greater compute drives client revenues higher, allowing them to afford both more chips from Nvidia and greater chip support.

Bull Case (Market Share of 90%)

Nvidia is considered a high-moat company. Once a company’s AI/LLM (Large Language Model) has been trained on CUDA, Nvidia’s proprietary AI software language, switching this investment to another language is nearly impossible on a cost-basis without starting from scratch. Further, as the LLMs develop in the years to come on this platform, this moat will only grow.

In that vein of thought, let’s assume the market share improves slightly to 90% over the ten-year period. This relies on the execution of the Rubin chips series, giving Nvidia its next foothold for further chip series. I can see this sort of long-term market share for other reasons as well: Nvidia is now writing chips with the use of its own AI, a feat no one else can do. Further, Nvidia can deploy its Blackwell chip to do the same work before anyone else even receives Blackwell. In short, Nvidia gets access to the latest AI chips and software to write the next chips better and before anyone else can. You can imagine this is part of why many consider Nvidia a well-moated company and part of its AA- credit rating.

Margins

I personally always use earnings at the R&D + EBIT level. This applies to companies with net cash positions only, such that interest payments on debt are countered by short-term investment income and thus aren’t material to the bottom line. I use EBIT instead of net income because it discounts non-recurrent costs.

I count R&D spending as earnings for three reasons:

1) R&D spend is real, claimable earnings funneled into the GAAP R&D line before it can get taxed at the net income level. Keen observers of income statements have known for a decade or more that companies like Amazon and Meta are far more profitable than their net income lines indicate. If Jensen wanted to stop all R&D tomorrow, he would claim something like an extra 40-50 billion USD in earnings (converted from R&D) more than his current operating earnings of 60B in the last 12 months.

2) Sometimes, those investments in R&D actually pay off. For example, what were Nvidia’s investments in the H100 worth in the last ten years? The cost of 10 billion USD over that period to develop the H100 has paid off handsomely, with 125 billion USD in sales slated for fiscal year 2025 alone, and much more to come. Clearly, it was worth multiples of their R&D cost. This is sometimes indicated via the “return on capital” metric, which uses similar (but not exactly the same) accounting principles. That figure for Nvidia is roughly 70% for the last twelve months. It roughly means “when Nvidia makes an investment, it returns 70% annually”. I am not counting Nvidia’s R&D at 1.7x it’s income statement value, or projecting out those R&D figures and discounting those cashflows back to the present, which one could conceivably justify. I am only counting them at 1x their stated value.

3) If you don’t trust management’s investments decisions in R&D, why own the company to begin with?

Bear Case (50%)

Margins in the last quarter were as follows:

Margin = (R&D+EBIT)/Revenue

Margin = (3.09B+18.642B)/30.04B = 72%.

Management also indicated that its mask improvements (known to the investment community as “Blackwell delays”) were the cause of a 3% loss of its gross margin. So we can assume a normalized margin of about 75% at the R&D+EBIT level as well. In ten years, if market share has fallen to 50% as stated in the above section, then margins have likely fallen significantly as pricing power vanishes. I’m going to assume a 50% margin here.

Bull Case (78%)

Consider that Nvidia’s competitors will remain writing their competing chips by hand, or, via chips that are less powerful than Nvidia’s Blackwell or Rubin series. I am putting forward that, given Nvidia’s chips are now writing the next chips and that power is solely in the control of Nvidia, pricing should reflect such enhanced performance over competition and thus, margins can actually improve slightly over the next ten years to 78% (again, at the R&D+EBIT level). This roughly coincides with market share expansion from 88% to 90%.

Multiples

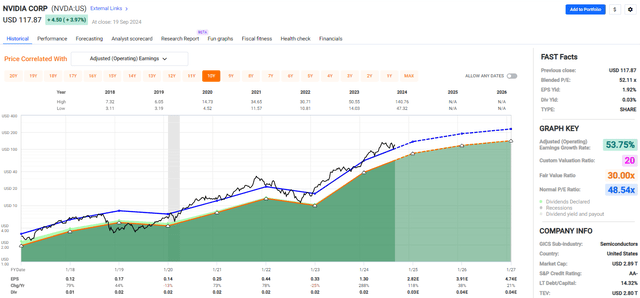

Nvidia stock has sold at a PE of 48.54 for the last eight years, on average, according to FastGraphs.

FastGraphs (www.fastgraphs.com)

At a current share price of a flat $116.00, Nvidia’s market pricing is about in line with average historical valuations. It’s enterprise value (EV), which factors in its net cash position, thus stands at $2.824 trillion USD. Last quarter’s R&D+EBIT, annualized, stands at 86.9 billion. That gives us a current multiple of 32.5, again which is about in line with average historical valuations.

Bear Case (20x R&D+EBIT)

In line with the bear case detailed in above sections, the multiple would be a fair amount less than the 30-35x my version of earnings (alternately, the 45-50x adjusted earnings) of the past eight years. Let’s assume a multiple of 20x on R&D+EBIT, and if you prefer adjusted (company reported) earnings, that would be roughly 30x.

Bull Case (35x R&D+EBIT)

In the bull case detailed above, such quality and sustained growth in ten years’ time would warrant a valuation closer to historical averages. I’m going to guess that range would hover around its current range, at 35x R&D+EBIT, or the same 48x adjusted earnings as the market has priced Nvidia in the last eight years. Notably, the market is likely currently only pricing Nvidia’s growth prospects. In ten years from now, I imagine the market will be pricing Nvidia by its moat, by that point either proven or disproven. Bear in mind that well-moated companies growing painfully slow, such as Coca-Cola (KO), are valued at an average of 22x earnings, despite sales growth of 1% annually over the last twelve years.

Putting It Together

This part is simple. The formula is:

10-year TAM x Market Share x Margin X Multiple = Ten-year Market Capitalization

Bear Case

1600B x 50% x 50% x 20 = Ten-year market capitalization of 8T

Now to my eye, we have a low downside risk where my bear case would give us a 2.8x on our investment in a decade. That is an 11% CAGR (compound annual growth rate).

Bull Case

2200B x 90% x 78% x 35 = ten-year market capitalization of 54T

The above would be a case where the Nvidia’s plans and growth are executed wonderfully, unimpeded by the risks below. But I should also mention that levels I’ve chosen for market growth, market share, margins and multiples in the bull case are not far off current figures. This means there is not much more to achieve, but much to maintain – a better position than having much to achieve.

Looking at the bear and bull cases, we can see that we have limited downside risk in the long term, compared with quite positive upside potential over the same period.

Risks

I’m going to detail four main risks associated with my thesis.

1) Recession – although I avoid considering market timing or recession timing, it’s true that a severe recession could cause earnings from Nvidia’s main clients (40% being Magnificent Seven companies) to decline, requiring them to slow down on R&D spending in the form of H100s and Blackwell chips in order to rescue their bottom lines. While I believe the demand would remain the same, this would cause a reset in the time period it would take to get all these chips sold. I don’t believe this breaks the thesis on company quality, but it could dampen expected returns.

2) Key Man Risk – Jensen is truly one-of-a-kind. He has been the CEO for 31 years, and loves his work. He works “all the time”, according to several interviews, stating that he will sometimes “sit through” a movie and not remember any of it because he is thinking about work. He also reportedly takes no days off and regardless enjoys his life. I intend to write an article expanding on Nvidia’s management quality, a subject worthy of more discussion than just a side note here.

To lose someone like Jensen, the leading Nvidia expert, would create a lot of doubt in the market as to whether someone else could bring that much work ethic and management quality to the company, and further, substitute Jensen’s vision for something else the market may not value the same way, which also may not work out.

3) AMD, Intel and the start-up community – several other companies, from old legends like turn-around Intel, to close competitors like AMD, to young start-ups like Groq and Etched, are attempting to build comparable or even superior chips. Groq in particular (cited above) is building a new way to compute such that kernels are automated, not handwritten, as in the case of Nvidia, potentially making compute far more scalable.

Further, Etched, another start-up, is banking on a proprietary innovation in transformers to “become the largest company in the world”, bypassing much of the innovation developed by Nvidia throughout the accelerated computing chain.

It’s worth noting that Jensen has used Nvidia’s cash pile to buy stakes in several computing and AI start-ups, meaning that should one of these companies end up being the future for accelerated computing platforms worldwide, Nvidia’s stake would grow with it, rewarding Nvidia’s shareholders regardless. This is useful for Nvidia’s shareholders, since most of these start-ups are still privately owned, meaning retail investors have no access to ownership outside of owning shares of Nvidia.

It’s far more likely, though, that Nvidia is buying stakes in these start-ups as a means to poach talent and intellectual property from them (a theme common with hyperscalers), and in that way absorb most of the value or potential these start-ups have. It protects the startups from going head-to-head with Nvidia, which could crush the start-ups innovations, and provides the start-ups the capital to grow optimally. Throwing 50 or 100 million into ownership stakes into each of the top several computing start-ups is easy for Nvidia, given its cash pile, and protects Nvidia’s future – it may not be the leader in twenty years, but it will own the leader.

4) Client concentration – Jensen Huang has indicated that about 45% of Nvidia’s data center revenue comes from hyperscalers (minute mark 15:39). To many, this translates into revenue concentration risk. If Nvidia’s largest client, Microsoft, switches to AMD chips, Nvidia would lose 15% of its data center revenue.

Frankly, I don’t see this as a risk. Presumably, Microsoft and others could stop buying from Nvidia and leave a hole in Nvidia’s revenue. This would only happen if AMD (or someone else) had a better pathway to creating the best chips. Currently, they do not, and the future looks to be in Nvidia’s hands with Blackwell and then Rubin.

Seen differently, why is 15% of revenue coming from an AAA rated company, and 45% coming from -AA-level or higher companies, not a fantastic thing? You want to be concentrated on high-quality clients, provided you can provide them with the best chips. The risk is on Nvidia to produce the best chips to maintain customers, not that those customers would for some other reason leave. There are companies that supply one product to one company. But, as an example, if that company you’re supplying is wide-moat Coca-Cola, and you’re the bottler for most of Coke’s drinks sold in Europe and the Middle East, you are in a better position with one client than you are having a diverse set of lower-quality purchasers who have to compete with Coke. So, in my view, the concentration is only a problem if Nvidia’s chips don’t remain the best.

I am not going to discount the other risks mentioned, as they are real. Instead, I am going to focus on the fact that as Nvidia sells the best chips in the world at the highest volumes, it’s installed base grows, and as compute gets deeper into industries across the world economy, the switching costs continue to become too high. Further, the value provided by Nvidia’s AI-written Blackwell and Rubin chips will at least be a strong buffer against most of the above risks.

Lastly, I want to reiterate that the timeframes that I have chosen (analysis over a ten-year period) are extremely conservative. Jensen himself has indicated (see YouTube video here at 35:39) that the timeframe to replace the first trillion in data center compute is four years (“call it four years” at 37:05), with the second trillion replaced by six years. I elected for a ten-year timeframe for the same two trillion dollar replacement schedule. Frankly, this skews the entire analysis negatively, even including my bull case, to ultra-conservative territory.

Conclusion

There is a lot more to Nvidia I’d like to detail in separate articles that point to how durable it’s competitive advantage is in accelerated computing as a platform. When investors get lost in the weeds of industry metrics, industry jargon, minute details, news, economics, fed rates, stock price swings and other information, it’s helpful to step back and consider four key considerations: markets, market shares, margins and multiples. I do this often to keep the big picture in check for most of my investments.

This article’s thesis hinges on whether or not you put stock in Jensen’s expectations of data center upgrades being in the 2 trillion dollar range. In my bear and bull cases, I accepted his claim and demonstrated that under such circumstances there is somewhat limited downside potential over the long-term (10 years, in this case), while the upside is pretty fantastic though at first glance somewhat unbelievable. I urge investors to consider both cases and figure out for their own risk tolerances what allocation, if any, should be given to Nvidia. As for me, with limited downside and huge upside, I consider Nvidia a Strong Buy.

Analyst’s Disclosure: I/we have a beneficial long position in the shares of NVDA either through stock ownership, options, or other derivatives. I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it (other than from Seeking Alpha). I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.

Seeking Alpha’s Disclosure: Past performance is no guarantee of future results. No recommendation or advice is being given as to whether any investment is suitable for a particular investor. Any views or opinions expressed above may not reflect those of Seeking Alpha as a whole. Seeking Alpha is not a licensed securities dealer, broker or US investment adviser or investment bank. Our analysts are third party authors that include both professional investors and individual investors who may not be licensed or certified by any institute or regulatory body.