Summary:

- NVIDIA dominates the GPU market with holistic hardware and software solutions, maintaining a strong position in the Server and Client GPU sectors.

- The company faces risks from supply chain issues, intensified competition, and potential regulatory challenges, but demand for AI-driven GPUs remains robust.

- Looking ahead, investors should keep a close eye on regulatory changes in China, technological advancements by competitors, and TSMC’s performance to improve their CoWoS packaging capabilities.

BING-JHEN HONG

Investment Thesis

Despite a 20% drop in share price from its peak following its latest earnings report, Nvidia (NASDAQ:NVDA) remains primed for growth, driven by its Blackwell hardware and robust software ecosystem, which create significant time and monetary switching costs for clients. With a price target of $145, this is a buy recommendation.

Earnings

Though the share price fell by 20% since earnings, we see that they beat EPS with a $0.68 Actual vs. a $0.64 Consensus, they beat revenue with a $30 billion Actual vs. $28.7 billion Consensus and analysts had given revenue guidance for Q3 as $31.6 billion, but it actually came in at $32.5 billion. Despite these earnings beats, the price fell because there had been double-digit surprises in earnings for the previous 3 quarters; November, February, and May at 19%, 13%, and 11%, respectively, but for the recent quarter, the surprise was only 6%. The market had expected continuous overachievement, but now they see a slowdown in growth.

The key point we can learn from the webcast is that Blackwell is not delayed:

“We executed a change to the Blackwell GPU mass to improve production yields. Blackwell production ramp is scheduled to begin in the fourth quarter and continue into fiscal year ’26. In Q4, we expect to get several billion dollars in Blackwell revenue. Hopper shipments are expected to increase in the second half of fiscal 2025.”

Additionally, China’s revenue segment grew in Q2, even with export controls, were moving forward they anticipate the “China market to be very competitive”.

Then they reiterate that “For the full year, we expect gross margins to be in the mid-70% range”, which is good to hear as you expect it to fall to this level as Blackwell uses CoWoS-L packaging, which then cannibalises H100s, as the jump in performance is too large, where the H100 uses CoWoS-S packaging which has better margins as it requires less manufacturing time. Also, it would reduce as it’s a new product ramp-up, where early production is more costly than in its later life where yields can improve.

With all this being said, in the earnings announcement, we are not worried about the stock price fall and instead see this as a buying opportunity.

Thesis Points and Tailwinds

Nvidia’s Holistic Solutions Create High Switching Costs

Nvidia is best positioned to meet client demands, offering the most holistic hardware solutions; covering CPUs and networking, all paired with powerful GPUs and a robust software ecosystem. The complexity and integration of these solutions create high time and monetary switching costs for clients.

We see Nvidia meeting client needs best, as although AMD (AMD) is comparable to Nvidia in several areas, including processors (i.e., CPUs), accelerators (i.e., GPUs), networking, and software—AMD’s networking capabilities, and GPUs are generally considered less robust compared to Nvidia’s offerings. For example, both Nvidia’s H200 and AMD’s MI300X GPUs were released in 2023, but AMD’s GPUs show lower performance in all data types in machine learning, such as FP16, BF16, and INT8, compared to Nvidia’s H100 and H200. These technical gaps translate directly into slower performance for AI workloads, reinforcing why Nvidia remains the top choice.

Nvidia’s real advantage, in our opinion, lies in its software ecosystem. While AMD and Intel (INTC) are catching up in hardware, neither has an equivalent to Nvidia’s AI software stack, which is critical for handling complex AI workloads across industries. This includes the CUDA parallel programming model and Nvidia AI Enterprise, a comprehensive suite of AI software, which is $4500 per GPU per year, which is required to be paid with every Nvidia GPU. Within the software suite, there’s Nvidia DGX Cloud, which allows users to train and deploy AI models over the cloud with access to Nvidia experts, which costs a minimum of $37,000 a month. They also offer Nvidia Omniverse, which helps design and simulate 3D assets and environments, such as for autonomous robots and vehicles. We argue that clients who build their workflows around Nvidia’s hardware and software face significant barriers to switching to competitors. Beyond the hardware investment, the cost of retraining teams, rebuilding code, and transitioning to less familiar or mature software introduces high switching costs, cementing Nvidia’s long-term client relationships.

Nvidia Likely to Retain 90% of GPU Market Share

We believe Nvidia will mostly maintain its 90% market share in the GPU space, where there is still a rapid demand for AI, with room to grow in the specialised chips market that includes ASICs and FPGAs, where they currently have an all-chips share of 64%.

Nvidia grew its market share by being a first mover in the high-end server GPU space, alongside AMD. However, clients preferred Nvidia due to its superior specifications. In our view, this lead is sustainable because of Nvidia’s consistent technological advancement, exemplified by its roadmap to release new architectures annually and as Blackwell is expected to be 30x better than the Hopper series in inferencing.

Though market share in the server GPU market is shared between Nvidia, AMD and Intel, we find that Nvidia competitors derive most of their revenue from CPUs. While in the server CPU and single-workload chip markets, the competition broadens to include not just AMD and Intel but also hyperscalers using ARM-based CPUs and FPGAs and ASICs, such as Google (Axion), Microsoft, Amazon (Graviton), and Meta (Artemis). However, these hyperscalers do not sell their custom chips to external clients, rather they use them internally for AI workloads.

While these hyperscalers produce AI chips like ASICs, FPGAs, or CPUs, they don’t produce GPUs as they are designed for multiple workloads and offer programmability, unlike ASICs and FPGAs. While they are efficient for single tasks, they lack the programmable flexibility of GPUs, making Nvidia’s solutions the preferred choice for a wider range of AI applications. This programmability is key because designing and producing a chip can take years, including 6 months of manufacturing, during which the initial workload it was intended for may become obsolete. Therefore, GPUs, with their ability to be reprogrammed for different tasks, provide longer useful lives compared to specialised chips.

So Hyperscalers still need GPUs, even if they produce their specialised single-workload chips, and we expect that they wouldn’t develop their own custom GPUs; The first reason is that they wouldn’t be able to match Nvidia’s performance, and a weaker GPU would not meet the needs of their clients, rendering the effort pointless.

Second is that it would be very expensive to produce a GPU with all its design complexity and hire hundreds of programmers to create complementary software with that GPU and continually improve and adapt it. Hyperscalers know that they can instead let Nvidia produce the GPUs so that they get the benefit of Nvidia’s mature software and software experts so that they can just focus on their core business rather than have to create and handle their own proprietary software and GPU issues.

The final point to make is that even if hyperscalers succeeded in creating a GPU, keeping it for internal use only would be expensive. So to justify the cost, they would need to sell the chip externally to other cloud service providers and AI firms. However, competing with Nvidia’s well-established market presence and maintaining an annual release schedule would be a major challenge, especially without the same level of experience or expertise in this space. Also, there would be no incentive for them to produce the best GPUs only to sell them to competitors, making it harder for their customers to prefer their service over competitors. This highlights that Nvidia is unmatched in the GPU Space and should be for a while, but we do believe they do have room to grow in the single workload chips market.

Server GPU Supply Constraints Expected to Ease

We anticipate that although the server GPU market is currently supply constrained, we expect these constraints to ease by 2026.

The reason behind Nvidia’s current supply constraints is the limited capacity for CoWoS packaging by TSMC. Chip-on-Wafer-on-Substrate (CoWoS) is an advanced packaging technology that combines memory and processors layer by layer, which significantly improves the density of the interconnections between the memory and processors, which leads to improved signal speed and power efficiency.

CoWoS-S is the most widely used, seen in GPUs like Nvidia’s H100 and H200. It uses a silicon interposer to connect chips. However, CoWoS-L, which will be used in Nvidia’s upcoming Blackwell GPUs, uses multiple silicon interconnects, which improves performance and yields. Despite these advantages, CoWoS-L is more complex and requires highly specialised machinery, to be precise, which increases manufacturing time, making it harder to meet demand without significant CapEx.

Our optimism about the easing of supply constraints by 2026 is driven by TSMC’s forecasted expansion of CoWoS capacity. If TSMC scales up its CoWoS-L production, we expect increased supply to meet the growing demand for the Blackwell Series.

Valuation

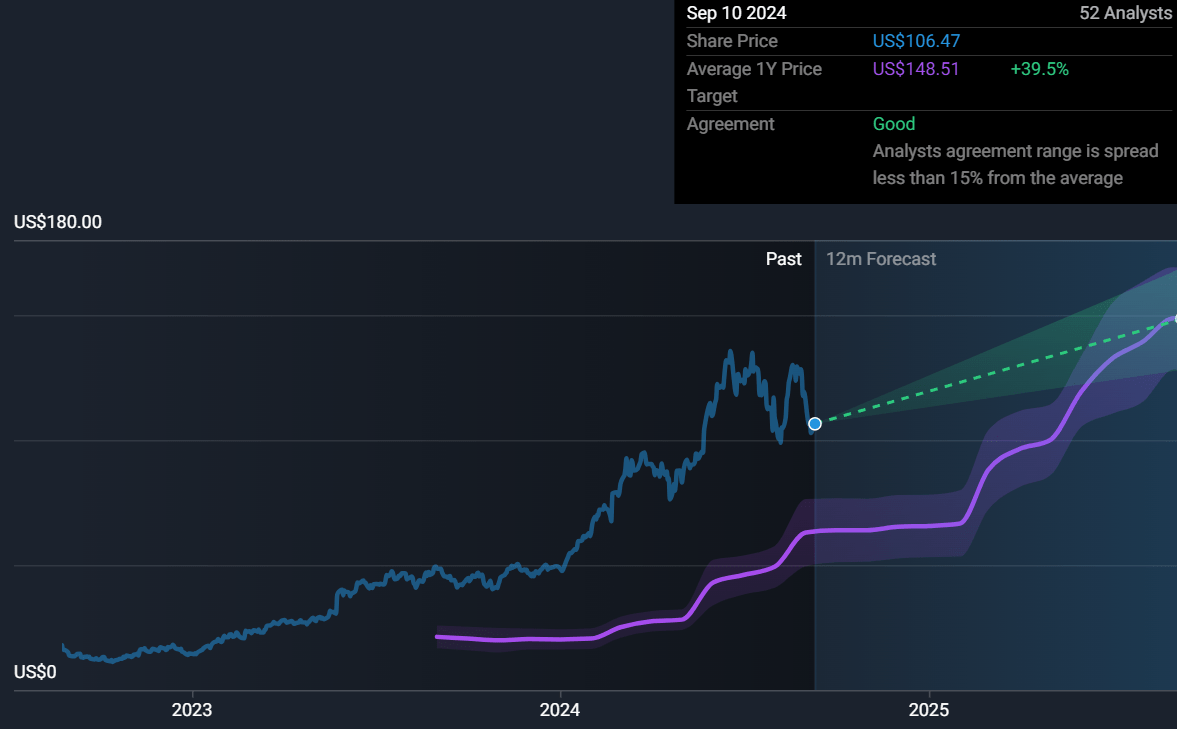

Intrinsic Valuation Compared To Analyst Forecast

simplywall.st

|

Intrinsic Valuation (NVDA) |

Analyst Forecast |

|

Price Target: $145 Current Price: $107 The Upside: 36% Derived via DCF |

Consensus Target: $148 (+38%) High End: $200 (+87%) Low End: $90 (-16%) |

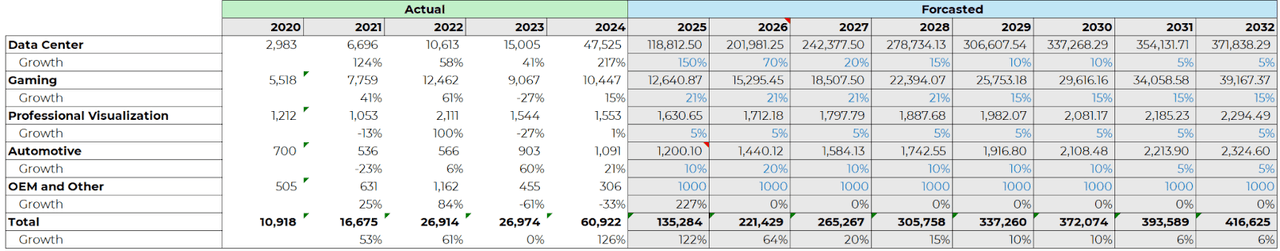

Nvidia DCF Forecast

Overview

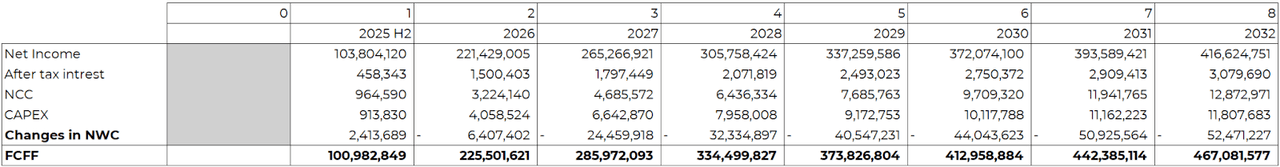

We calculated free cash flow to the firm from the second half of 2025 to 2032. We then get to EV by summing all discounted FCFF, including terminal FCFF. Then we use the EV bridge to get to the Market Value of Equity and divide it by its outstanding number of shares.

Revenue Estimates

Revenue Actual vs Forecasted (Market Snippet)

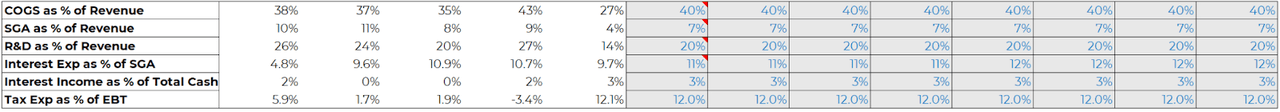

Income Statement Assumptions

Income Statement Assumptions (Market Snippet) DCF (Market Snippet)

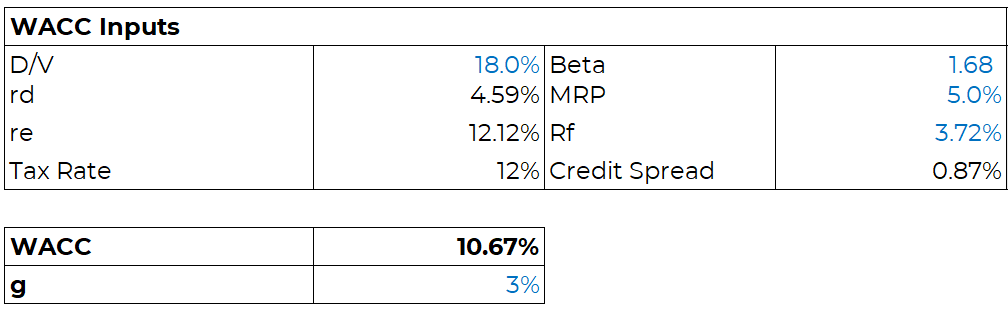

WACC Inputs and Terminal FCFF Growth Rate

Inputs (Market Snippet)

Estimates vs Consensus

While Morgan Stanley projects that Blackwell will generate $200 billion in revenue by 2025, we disagree and see this figure being achieved in 2026 for the company as a whole. The discrepancies between our valuation and the markets arise from differing assumptions. Although both we and the market expect supply to remain relatively tight in 2025 for the Blackwell Series, we believe that by 2026 and 2027, the supply of server GPUs will ease significantly, leading to higher revenue estimates for server GPUs compared to consensus.

Additionally, we expect automotive sector revenue to grow faster than the market sizing specialists anticipate, with our projection at 10% compared to theirs at 3%. This growth would outpace the professional visualisation space, which we estimate at 5%, but still lag behind the gaming client GPU segment. For the gaming segment, we project a 21% compound annual growth rate (CAGR) until 2028, after which it slows to 15%. This segment could also benefit from synergies and compatibility with the server GPU sector.

Upside vs Downside

The potential reward is 36% based on our estimates, while the downside risk is -13% according to consensus, resulting in a 2.8x risk/reward ratio.

Valuation Closing Remarks

Based on our DCF model, we believe that Nvidia is worth $145. Buying before it reaches $115 is ideal, as you could still net an almost 30% return with a fair margin of safety. It’s best to buy now rather than later, as the market will likely turn bullish on Nvidia once Q3 earnings are released with Q4 guidance, where we should see a surge in its price from anticipated Q4 Blackwell revenue. For the $145 price target to be reached, the earliest and least likely time it could happen is after the Q3 announcement when guidance for Q4 is provided, while the more likely time would be Q1 of the following year, once the market has had time to process two-quarters of Blackwell revenue being recognised, and future revenue is more determinable with less uncertainty. It could also just as likely happen with earnings announcements from FY2026, as a price target like this factors in consistent revenue growth, such that FY2029 revenue would more than double FY2025 revenue. Most investors wouldn’t have the tolerance to price in this value early with so much uncertainty.

Risk Points, Headwinds and Challenges

GPU Component Supply Shortages or Issues

A GPU requires numerous suppliers as it contains thousands of components. For example, for the Blackwell, the NVL switch chip connects multiple GPUs, while smart switch chips link racks together. This creates a complex architecture, where any supply chain disruption can delay Nvidia’s yearly GPU releases, as even a single component failure can have cascading effects throughout the ecosystem.

There were rumours that Nvidia’s upcoming Blackwell GPU was delayed due to design flaws, raising concerns about supply. However, these rumours were unfounded. Nvidia clarified that there were no design flaws or delays. Instead, the challenge lay in the precision limitations of TSMC’s machinery. Blackwell uses CoWoS-L packaging, which requires extreme accuracy in placing and linking components. Small margins of error at TSMC led to warping and system failure during heating, forcing Nvidia to redesign the GPU’s silicon top metal layers to improve yields (i.e., the percentage of successfully produced Blackwell chips at TSMC).

In our view, even if supply shortages or delays were to occur, they would have minimal long-term impact. Customers would continue to purchase previous-generation GPUs, just as they did with the Hopper series, and those needing less power could opt for the B200A, which reportedly replaced the B100. The B200A uses CoWoS-S, a packaging technology with fewer issues than CoWoS-L, making it less likely to experience delays.

The reason we believe cloud service providers would continue to buy previous-generation GPUs in the event of delay is because the clients of these cloud service providers are training and inferencing Large language models (LLMs), which must be continually trained and fine-tuned to stay competitive in the AI race, especially in generative AI, where time-to-train is critical. Cloud service providers know this expectation from clients, so they know it’s crucial to meet this demand to maintain market share by providing the best cost-to-performance ratio, if not, then clients would go to a provider that offers better value as the service itself is commodity-like and there isn’t much differentiation unless you have the best infrastructure specs or cheapest price.

Demand Slowdown by CSP or their clients

Another potential risk to the thesis that can impact our forecasted valuation is that cloud service providers in the future could provide lower than expected guidance on CapEx, the market would then assume that demand for Nvidia GPUs is overestimated, perhaps due to slower client demand for high-end infrastructure capabilities or hyperscalers seeing less instrumental value in upgrading, regardless this would lead to strong price corrections. However, CapEx guidance could be lower due to hyperscalers needing less land and fewer facilities to house their new data centres, but the subsegment of GPU CapEx could increase, where then Nvidia revenue estimates would beat what was expected based on lower total CapEx guidance.

When it comes to slowing client demand for high-end infrastructure, we believe this is unlikely as it is a new and growing industry, where these firms are trying to create the next dominating model or AI product to add value across almost all sectors, and to do this, they expect the best capabilities to train and inference their large language models ie LLMs. It is therefore unlikely that cloud service providers will reduce CapEx, as they understand their client’s expectations and want to provide the best cost-to-performance ratio, since if not, then clients may turn to a provider offering better value, as the service itself is commodity-like and there is little differentiation unless you have the best infrastructure specifications or the cheapest price.

Suppliers’ Specifications Plateau

There is a risk that Nvidia’s suppliers may not keep up with the yearly GPU releases, as improved specifications also rely on suppliers to improve the performance of their components annually, examples include TSMC’s packaging and HBM solutions etc. If Nvidia’s performance jumps between generations slow down due to supply performance plateaus, then this would make it easier for competitors like AMD and Intel to catch up, weakening Nvidia’s market position. This would also lead to falling demand for Nvidia’s next series due to Nvidia’s declining cost-to-performance ratio as hyperscalers would prefer not to upgrade their current Nvidia infrastructure, to save money.

Intensified Competition

Another risk to our thesis is that competition increases from Cloud Service Providers developing their own chips: such is the case with OpenAI, Meta and Google who are in talks with Broadcom to develop custom chips like CPU, TPUs, ASICs solutions or FPGAs. This poses a risk of reducing Nvidia’s current all-chips market share of 64%, where if this were to fall further, it could really impact its current valuation and how it can grow in the future from a weakened market position. To mitigate the impact of competition in the specialised single workload chip space, though not officially announced, Nvidia has formed a new business unit to address this market, where Dina McKinney, a former AMD and Marvell executive, heads Nvidia’s new unit, so progress is being made to address this issue, but it’s still too early to make a verdict on whether they can maintain their position or lose most of it. Instead, there should be great concern if competition in the server GPU space increases, which we argue is unlikely in thesis point 2.

Increased Regulation

Although Nvidia can currently sell H20s overseas in China, there is a risk that future regulations could impose stricter tariffs and quotas, which would hamper sales figures and enable more competition from domestic Chinese talent. In FY2024, 17% of Nvidia’s revenue was generated from China, and any weakness in this area would pose a significant risk to its current valuation. But even if this figure were to fall, it’s possible that individuals in China could buy resold GPUs off the black market, resulting in higher Nvidia revenue to compensate for the lower figure in the reported China segment.

ARM License or TSMC Issues

The final, more speculative risk is that Arm Holdings, who license and provide the energy-efficient ARM architecture for CPUs, could increase their fees, or they can’t provide Nvidia access to its architecture. The risk of increases in fees is likely, but to restrict Nvidia’s access to the architecture is not, as there would be no incentive to lose a big customer, and other customers would recognise this risk and look for alternatives. Instead, ARM could somehow find issues in providing the architecture to all customers due to unforeseen circumstances, if so, then no competitor of Nvidia would have a competitive advantage in this respect and so this shouldn’t be an issue unless it’s necessary for the stability of their products.

Similarly, TSMC could try to exert monopolistic power over Nvidia, but this is unlikely until the supply of chips meets demand, and by that time, Nvidia could choose to have its chips manufactured by Samsung or even Intel, provided Intel can increase their transistor density capability to meet the standard needed so that Nvidia can even use their foundry.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Nvidia remains the dominant player in the server GPU market, solidifying its leadership with a robust hardware and software ecosystem, which creates high switching costs. While AMD and Intel, we believe, would continue to trail behind in crucial areas such as GPU performance and software offerings. We argue that Nvidia will maintain most of its 90% market share in the GPU space, but they likely would have limited growth in specialised chips like ASICs and FPGAs as their clients continue to develop their own customer chips for single workloads. And despite hyperscalers developing their own chips, these are not GPUs, and we don’t foresee them developing their own custom GPUs, and we see supply constraints easing by 2026, allowing supply to meet the demand for Blackwell.

However, there are risks to monitor. Increased regulation, especially in China, where 17% of Nvidia’s revenue is generated, could pose a significant threat to the company’s revenue streams. Additionally, supplier specification plateaus and competition from hyperscalers developing their own specialised chips could apply pressure on Nvidia’s cost-to-performance ratio and market share.

Looking ahead, investors should keep a close eye on regulatory changes in China, technological advancements by competitors, and TSMCs performance to improve their CoWoS packaging capabilities. In light of our analysis, Nvidia’s prospects remain promising, as the demand for AI-driven GPUs continues to grow across sectors. Moreover, Nvidia, as a technology company, has the flexibility to adjust both its R&D and revenue recognition, allowing it to meet or exceed market expectations strategically.

Analyst’s Disclosure: I/we have no stock, option or similar derivative position in any of the companies mentioned, and no plans to initiate any such positions within the next 72 hours. I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it (other than from Seeking Alpha). I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.

Seeking Alpha’s Disclosure: Past performance is no guarantee of future results. No recommendation or advice is being given as to whether any investment is suitable for a particular investor. Any views or opinions expressed above may not reflect those of Seeking Alpha as a whole. Seeking Alpha is not a licensed securities dealer, broker or US investment adviser or investment bank. Our analysts are third party authors that include both professional investors and individual investors who may not be licensed or certified by any institute or regulatory body.