Summary:

- PYPL is facing fierce competition and may need to invest more money in innovations to differentiate its products.

- PayPal’s weak moat and strong competition in the industry pose long-term challenges to the company’s growth.

- I confirm my Hold rating on the stock.

Justin Sullivan/Getty Images News

I rate PayPal (NASDAQ:PYPL) as a hold, as I believe the management was not clear about the future guidance of the company in the last call for the Q4 2023 results. It’s clear that CEO Alex Chriss is making several changes and innovations in order to construct new avenues of growth, but meanwhile, he might need to invest more money in those endeavors as the company faces fierce competition from other players who are investing heavily as well to offer the best products at lower fees to improve the customer’s experience. This context reveals a very limited room to differentiate their products for the players in this industry in the long haul. I think that this uncertainty about the real future possibilities of PayPal delivering double-digit growth is what might be causing a poor performance in the stock right now. I wrote about PayPal in October 2023, showing that I was not optimistic about PayPal’s long-term prospects, even when the stock price seemed cheap then. I will confirm this with my calculation of the intrinsic value with more updated information.

Context

In its last report for FY2023, PayPal showed a revenue growth of 8.19% YoY, a growth of net income of 75.53% YoY, and a growth of free cash flow (FCF) of -17.3% YoY, though still good FCF, which represents 14% of total revenues. However, it’s clear that over the last 10 years, PayPal has reduced its double-digit revenue growth, which was between 15% and 20% in the period 2016-2021. Not only that, its FCF margins were between 14% and 30% in those years, and now we are talking about a company that grows at a single digit with a downward trend in its FCF margins as they are declining from 2020, when the company reached a FCF margin of 23%.

PayPal’s debt levels are healthy, but they are increasing; for instance, if I take the ratio of total debt to FCF, I can see that it was growing gradually from 1.5x in 2019 to 2.3x in 2023. Not only is the market seeing some downward trends in some important metrics, but the guidance recently given by the new CEO, Alex Chriss, supports our main thesis that PayPal’s problem is more structural and related to the nature of the business:

Before turning to our first quarter and 2024 guidance, I have 2 updates to our guidance approach to share. First, for the time being, we intend to move away from providing annual revenue guidance and instead provide guidance for the upcoming quarter. Given the considerable changes underway at the company, we believe it is prudent to guide revenue 1 quarter ahead and provide updates as the year progresses. Second, the first quarter and 2024 guidance that we’re providing today excludes the impact of stock-based compensation from our non-GAAP results. This is consistent with our historical approach.

This is what I was mentioning in my previous article about PayPal’s structural problem: there’s so much competition in the industry that PayPal might need to invest more in innovations. I said the following in that article:

this is a very challenging strategy for the company because it implies that most of these new innovative services must really contribute to generating more profitable growth, which is not guaranteed, at least in a very consistent way, adding to the higher R&D expenses needed to launch those new initiatives. With restrictions on raising its fees and a limited room to reduce costs, there will be pressure on the margins over the long term.

In this sense, given the lack of predictability of those new initiatives, Alex Chriss wants to move from annual guidance to quarter guidance in order to see if those initiatives will deliver profitable growth or not. We need to think that if PayPal is making efforts to construct new avenues of growth, competitors are thinking exactly in the same way; companies such as Adyen (ADYEN), Block (SQ), or Striple, which is not publicly traded yet, are very innovative companies pushing themselves to offer the best experience to their users, so you can imagine how hard it is to have pricing power in this industry.

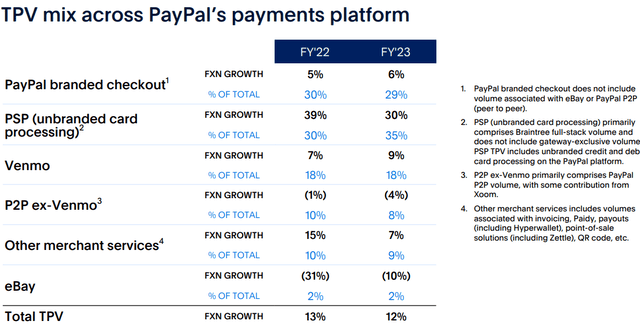

Revenue Breakdown FY2023

In the last PayPal investor presentation in February 2024, the company showed the following:

Investor Presentation Feb, 2024

Even when branded checkout and PSP (unbranded card processing), commonly known as Braintree, represent both 64% of the total revenues of 2023, these two segments are more mature, so PayPal would need to focus its efforts on offering more services per user while developing more of the segments of Venmo, P2P, and other merchant services. It does not seem like an easy task to attack many fronts to deliver decent growth in the next few years.

Some Important Trends Seem To Confirm These Difficulties In The Business

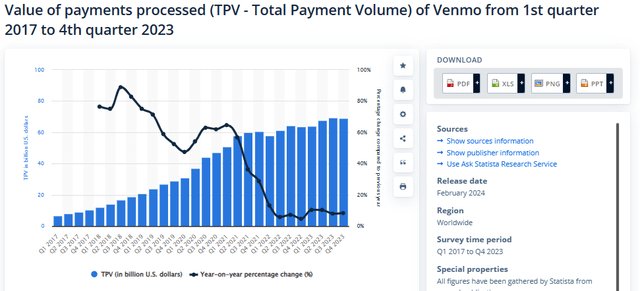

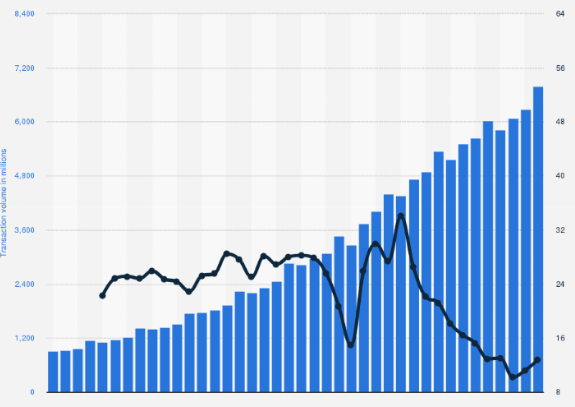

I mentioned several metrics in my previous article, such as the value of payments processed (TPV), which showed a clear deceleration since Q1 2021, and the take rate, which showed a clear downward trend from Q1 2015 to Q1 2023. Do not forget that the take rate is how much money the company makes in each transaction.

This is the take rate evolution from Q1 2010 to Q3 2023:

Statista

With the acquisition of Honey Science for $4 billion in 2019, PayPal was expected to increase its take rate as Honey’s business would enable PayPal to increase its role in the customer’s shopping experience beyond a payment processor service. However, the chart shows that the take rate continues its downward trend even after the acquisition of Honey.

In the first three quarters of 2023, there was a rebound in the take rate’s evolution, which is an indication that some of Chris’s changes are having some interesting outcomes; however, his initiatives would need to be consistent over the long haul, which is certainly challenging.

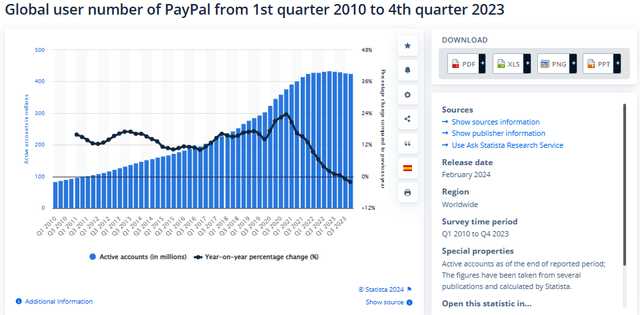

More updated information related to the number of users reveals that there is a deceleration in the number of global users, so if PayPal wants to deliver more future growth, it would need to increase the number of services per user through more innovations:

A similar trend could be seen with Venmo’s TPV until the last quarter of 2023:

New PayPal Initiatives Support My Thesis Of A Weak Moat; Buffett’s Savviness Might Give Us Answers

In the last call for the Q4 2023 results, CEO Alex Chriss explained the different innovations PayPal was working on, such as the new guest checkout experience Fastlane, which adds value to merchants and shows a number of interesting metrics. For instance, Fastlane enables merchants to recognize up to 70% of guests visiting that merchant while reducing the checkout time by up to 40%. Chriss mentioned that one of PayPal’s long-term partners, an e-commerce company, implemented Fastlane, helping its merchants achieve a conversion rate of 79%.

Of course, that sounds very encouraging, but the first question that a long-term investor should ask himself is if those new solutions can be easily replicated by PayPal’s competitors.

On the other hand, Chriss mentioned that PayPal is working on redesigning its branded checkout experience, increasing the speed while reducing friction across all major checkout flows. This could be seen through a 50% drop in latency thanks to a quicker process of payments. Of course, these improvements could contribute to a better customer experience, but again, I am not sure if all those efforts could deliver the growth expected in the context of strong competition, where competitors are making huge efforts to deliver the best customer’s experience through more innovations.

My point is that all the effort put in by Chriss and his team is very rational; in fact, I would take the same path taken by Chriss if I were PayPal’s CEO, focusing on the segments that would deliver the most profitable growth through more innovations to improve the customer’s experience. Nevertheless, this kind of situation reminds me so much of Warren Buffett’s experience with the textile business.

This is what Buffett said in his 1985 letter to shareholders:

Over the years, we had the option of making large capital expenditures in the textile operation that would have allowed us to somewhat reduce variable costs. Each proposal to do so looked like an immediate winner. Measured by standard return-on- investment tests, in fact, these proposals usually promised greater economic benefits than would have resulted from comparable expenditures in our highly-profitable candy and newspaper businesses.

But the promised benefits from these textile investments were illusory. Many of our competitors, both domestic and foreign, were stepping up to the same kind of expenditures and, once enough companies did so, their reduced costs became the baseline for reduced prices industrywide. Viewed individually, each company’s capital investment decision appeared cost- effective and rational; viewed collectively, the decisions neutralized each other and were irrational (just as happens when each person watching a parade decides he can see a little better if he stands on tiptoes). After each round of investment, all the players had more money in the game and returns remained anemic.

Thus, we faced a miserable choice: huge capital investment would have helped to keep our textile business alive, but would have left us with terrible returns on ever-growing amounts of capital. After the investment, moreover, the foreign competition would still have retained a major, continuing advantage in labor costs. A refusal to invest, however, would make us increasingly non-competitive, even measured against domestic textile manufacturers. I always thought myself in the position described by Woody Allen in one of his movies: “More than any other time in history, mankind faces a crossroads. One path leads to despair and utter hopelessness, the other to total extinction. Let us pray we have the wisdom to choose correctly.

What Buffett experienced with the textile industry is a very good learning business case since it’s clear that weak-moat businesses need to reinvest continuously, not to deliver long-term value but to just keep their current market position, as those businesses do not have much pricing power. They need to offer more innovative services at lower prices because competitors are doing exactly the same, so all these players end up seeing lower prices for their services, lower margins, more debt, more R&D expenses, lower growth, etc.

With regard to the management, Warren Buffett reminds us of something he experienced by himself:

When a management with a reputation for brilliance tackles a business with a reputation for bad economics, it is the reputation of the business that remains intact

I do not think that PayPal is a bad business since the company is profitable, generates good free cash flows, and has decent revenue growth; however, in all my articles, I mentioned my vision that I invest with a long-term horizon, so the bad economics of a company with a weak moat can be seen better over a longer period of time. A good example of the latter is Berkshire Hathaway, since it was a textile company at the beginning, and Buffett used the free cash flow generated for several years from 1965 to 1985 to acquire other excellent businesses with heavy moats.

The problem was that the company was consuming so much cash and resources during all those 20 years just to keep its market position while facing fierce competition. I am not saying that the textile business is equal to the payment processor industry, but we can see that there are some similarities in terms of how strong the competition is and how that competition erodes margins over time while pushing down prices; one example of the latter is the downward trend of the take rate that I showed before.

A heavy-moat company that is developing more innovative services that are well received by customers is adding value to its shareholders over time; conversely, a weak-moat company that is developing more innovative services that could be replicated by its counterparts is destroying value as it needs to do those innovations just to keep its current market position, reducing prices and margins over time.

Valuation

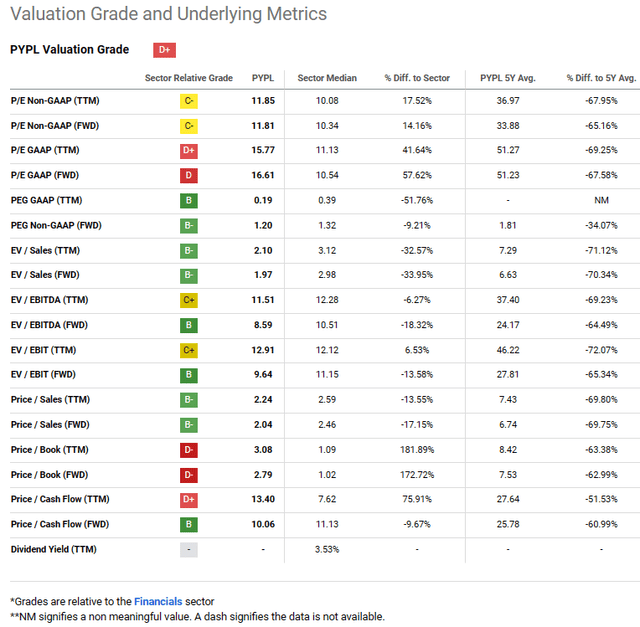

Looking into some of the valuation multiples provided by SA, I can see that PayPal is cheap using some ratios and expensive using others, but it received an overall grade of D+, which is not precisely cheap compared to its sector.

I like to see EV/EBIT and EV/FCF, but I can only see the first one in SA’s table. Now, SA gives us the EV/EBIT (TTM), which shows that PayPal is very close to the multiple of the sector, whereas the EV/EBIT (FWD) indicates that PayPal is cheaper than its sector.

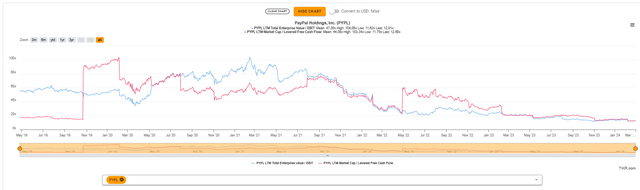

If we go to TIKR Terminal to see if PayPal is cheap compared to its past valuation, we can see the following:

Looking into the chart, I see the evolution of EV/EBIT and EV/FCF, and we can see that PayPal is very close to its cheapest valuations over the last 5 years, and maybe that is the reason why some analysts think that the stock is a strong buy. However, given my very long-term horizon, the fact that PayPal seems cheap is not enough reason to buy it, as I previously mentioned about how important the qualitative aspects are for a long-term investor.

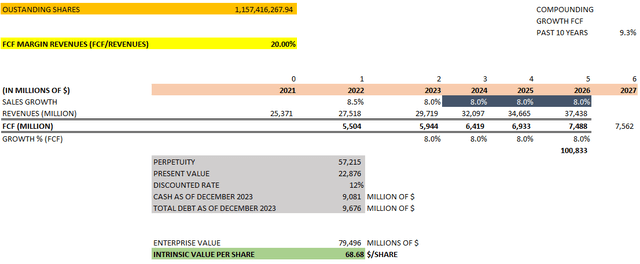

Now, I want to use a method that enables me to control some of the assumptions that show my perspective more clearly about the company. In this sense, I will use the DCF, so I’ll need to make some assumptions:

- Outstanding shares: 1,157,416,267 (as of December 2023)

- FCF margins: 20% (average of the last 10 years).

- Revenue growth: 8% for the next few years (aligned with the consensus)

- Cash as of December 2023: $9,081 million.

- Debt as of December 2023: $9,676 million.

- Discounted rate: 12% (I use this discounted rate to somehow incorporate the higher risk associated with a company with a weak moat, particularly for a long-term holding.).

- FCF growth in perpetuity: 4.5% annual (CAGR FCF growth over the last 10 years of 9.3%).

To find the perpetuity, we used the formula:

Perpetuity = FCF 2027/(discounted rate – g).

Where g = FCF growth in perpetuity, which was assumed to be 4.5% annual.

With perpetuity, we calculate the present value of all the FCFs beyond 2027. Then, we calculate the enterprise value using the following:

Enterprise Value = Present Value of FCF (from 2023 to 2026) + Perpetuity + Cash – Total Debt.

Finally, the intrinsic value is calculated by taking the enterprise value and dividing it by the outstanding number of shares. In this way, we could get $68.68 per share under the assumptions presented. Compared to the current stock price of around $60 per share, there is not enough margin of safety, which is a very important concept for a long-term investor.

Of course, the intrinsic value could be higher if the revenue growth is higher than 8% in each of the next two years, but we are not sure about the outcomes of those initiatives led by Chriss to deliver higher growth. Furthermore, he is not so sure about them either, as he mentioned that, from now on, he will deliver only quarter guidance instead of annual guidance. I think that PayPal can deliver annual revenue growth of around 8% in the next few years, so an intrinsic value of $68 per share seems conservative.

Risks

A risk to my thesis is that Chriss surpasses the consensus’s expectations in each of the next quarters, which might give confidence to the market, rewarding PayPal with higher multiples. Nevertheless, we need to remember that this thesis is based on the fact that we are long-term holders, so it does not matter if the company exceeds its expectations in the short term because the company’s structural problems are still there.

It’s very important that investors know exactly why they are invested in PayPal; if your horizon is not long-term while expecting short-term catalysts, PayPal could be an opportunity. However, if you just want to buy the stock at the current price to accumulate shares to hold it for several years, PayPal might not fit this kind of strategy due to the structural problems I mentioned in this article about its weak moat and the fierce competition in its industry.

Final Thoughts

CEO Alex Chriss is making a lot of efforts to please PayPal’s investors through different innovations in order to improve the customer’s experience and differentiate its products and services given the strong competition in the industry. However, these steps taken by the CEO might not deliver the expected results since PayPal does not have a strong moat that protects its business model from competition.

Even when it’s possible that PayPal could surprise investors by delivering some positive short-term catalysts eventually, things are not that positive for long-term investors as PayPal would need to keep developing more and more services that could be replicated by competitors, so the company might be putting in so much effort to keep developing more innovative services until a point where there are limitations to keep generating more value.

Meanwhile, so many resources and liquidity are spent on this path to make PayPal’s services unique until they are replicated by their counterparts. Chriss wants to build up an ecosystem from which it would be very difficult for a customer to get out. I would say that this is very challenging, particularly for a company whose customers are not that loyal to the brand.

Editor’s Note: This article discusses one or more securities that do not trade on a major U.S. exchange. Please be aware of the risks associated with these stocks.

Analyst’s Disclosure: I/we have no stock, option or similar derivative position in any of the companies mentioned, and no plans to initiate any such positions within the next 72 hours. I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it (other than from Seeking Alpha). I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.

Seeking Alpha’s Disclosure: Past performance is no guarantee of future results. No recommendation or advice is being given as to whether any investment is suitable for a particular investor. Any views or opinions expressed above may not reflect those of Seeking Alpha as a whole. Seeking Alpha is not a licensed securities dealer, broker or US investment adviser or investment bank. Our analysts are third party authors that include both professional investors and individual investors who may not be licensed or certified by any institute or regulatory body.