Summary:

- Netflix is overpriced due to limited potential subscribers, historical data showing low revenue growth rates for companies of its size, and high discount rates for future cash flows.

- Analysts estimate Netflix’s revenue to reach $77.4 billion by 2032, but I believe this is too optimistic based on demographic forecasts.

- A discounted cash flow analysis suggests a reasonable stock price for Netflix is around $200-$220 per share, indicating that the current stock price is massively overvalued.

Riska

I felt like reviewing Netflix, Inc. (NASDAQ:NFLX) again, so I’m going to review Netflix Inc. again. I want to review the assumptions embedded in the current price, and I want to forecast what I think is a reasonable stock price for the firm by using a few different approaches. I want to start by offering a quick review of what the analyst community is forecasting here. I’m then going to remind investors of some work I did on the demographics of Netflix’s potential market. I’m going to use Mauboussin’s work at Credit Suisse to review how many companies of Netflix’s size have grown revenues at the rate Wall Street is forecasting. I’m going to conclude my analysis with a DCF analysis of the business to come to a reasonable stock price.

This one’s a long one, so I’m not going to beat around the bush in this thesis statement with ridiculous jokes about needing to save time so I can catch up on Soap Operas or whatever other nonsense I sometimes write. I’m of the view that Netflix is morbidly overpriced for a few reasons. First, nothing’s changed my original view that there are only about 365 million potential subscribers globally. Second, history indicates that only about 20% of companies of Netflix’s size achieve revenue growth rates that are currently assumed by Wall Street, suggesting inevitable disappointment. Finally, given the elevated yield on the 20 year Treasury Bond, future cash flows should be discounted significantly. The resulting value of the discounted cash flows is about $200 for my analysis, and only about $217 using Wall Street’s very optimistic forecast. So, I’m going to start buying deep out of the money puts on this stock using risk capital I can afford to lose. The value of these may go to zero as the shares continue to rise, but I’m of the view that the higher the stock price, the greater the eventual payout.

So the analyst community is estimating that Netflix revenue will reach about $77.4 billion, and EPS of $60.90 by 2032. In a previous article, I poured over demographic forecasts and determined that there are about 365 million households on Earth that are in a position to pay for a Netflix membership. That was a forecast made in 2019, before the onset of global inflation, so in my view the forecast is on the high side. That written, I’ll start with it as a base case. The company currently boasts 238.4 million memberships, so there are about 126 million more to go.

At the moment, the company generates about $138 per year per user. If we assume the company maintains the same membership growth rate that it has over the past four years (CAGR of 10.7%), the company will reach 365 million memberships in about 4 years. If we also assume that the company can grow per membership revenue at a rate of about 2% over those four years and beyond, we have revenue per membership of $149 in the fourth year. Using the arithmetic skills I learned decades ago, I estimate that the annual revenue for the firm in four years will be about $53.4 billion. This is actually pretty close to the revenue forecast posited by analysts for the year 2028, and I’ll admit that being this close to Wall Street makes me a bit nervous.

Anyway, the point so far is that there are a finite number of potential memberships on Earth, and I think the company will saturate potential memberships in about 4 years. At that point, the company turns into the proverbial “cash cow.” This particular cash cow is obviously very valuable, and I want to eventually forecast future cash flows, but I want to first review some economic history.

Returning To Mauboussin

For those paying attention, you know that Wall Street’s $77.4 billion of revenue in 10 years is considerably higher than mine. I think revenue growth will be a function of increases in membership rates once every potential Netflix subscriber has a subscription. Also, Wall Street’s $77.4 billion sales estimate is a CAGR of about 8.64%. This may be a very reasonable forecast, and it may take into account new businesses that the company enters over and above the subscription model. It may decide to start selling Reed Hastings action figures, for instance, and these may take off in popularity. So, it’s quite possible for Netflix to get involved in some other businesses, and thus it’s possible to generate revenue beyond the streaming service.

It’s now time to think about Wall Street’s forecast from a slightly different angle, and we’re going to use some market history in order to do that. The question I have of the Wall Street forecast is “what percentage of companies, starting from Netflix’s current size, have grown revenues at a CAGR of 8.64% over the next decade?”

Thankfully, an analyst that I respect a great deal, Michael Mauboussin, along with a few colleagues has answered that question for us. You can find the answer to that question in this very worthwhile document. If you turn to page 21, you’ll get an explanation of what the good people at Credit Suisse did some years ago, and the methodology employed. In a nutshell, they analyzed a host of global companies by base sales levels, from the years 1950-2015. They then calculated subsequent CAGR sales growth for each firm and charted the results. They were trying to work out how likely it was for companies starting with a certain level of sales to grow those sales at a certain rate. Put another way, it answers the question “what does history show us about companies of a certain size achieving certain growth rates over the coming decade?” One of the ideas is that the bigger the company, the harder it might be for it to grow revenues at a high rate.

The analysts divided each of these companies into deciles of varying sales growth. So, if you turn to page 25 of the document, you’ll find the “Sales >$25,000 million,” which is where Netflix finds itself today. If you then go down the first column of sales growth to the row marked 5-10, that’s relevant to Netflix forecast, because 8.64% implied growth is between 5%-10%. You then go across to see what percentage of companies starting with Netflix’s base revenue managed to grow revenue at a CAGR between 5-10% over the next decade. The answer is 20.2%, or 583 companies of the 2,886 companies in the sample that both started the decade with sales of $25 billion or greater, and survived the decade. So, I’d characterize the historical precedent here as “ok, not great”, given that most (60%) companies sported growth rates between -5% and 5%. It’s hard for big companies to grow.

Reintroducing my stuff on demographics compounds the problem in my view. Assuming the company manages to grow per membership revenue at 2% (a heavy lift in my view), and assuming they don’t find a group of new humans to sell to, revenue in 2032 will be about $61.4 billion, or about 21% below Wall Street’s estimate. This still represents a very optimistic (in my view) CAGR in revenue of about 6.2%, so I think $61.4 billion is on the high side. As I wrote earlier, it’s possible for the company to generate another $16 billion over and above the membership business in 2032, but I wouldn’t bet much money on that possibility. I’d conclude this section of my analysis by reminding investors of hundreds of years of economic history: a new entrant comes into a space, generates amazing profits, those profits attract competition, which drives down the level of profitability. That’s a recurring theme throughout economic history. The idea that other streamers, or some as yet unborn streaming service, won’t take profits from Netflix is a very fanciful notion in my estimation.

So, even if we take Wall Street’s estimate as a given, only 20% of companies of Netflix’s current size ever achieve that growth rate. We then overlay the fact that the Wall Street forecast seems wildly optimistic based on the simple reality of demographics, and we have a very optimistic forecast indeed.

DCF Forecast

I feel the need to “triangulate” my view that the market seems quite optimistic here with a DCF analysis that lines up future cash flows with what I would consider to be a reasonable price for the stock. In case it’s been a while since you’ve subjected yourself to this sort of exercise, I’ll remind you that the price of any asset (including a stock) is the present value of future cash flows that the asset will generate over time. Because money comes with an opportunity cost, and because the future is uncertain, we “discount” these future cash flows by a certain rate depending on a few variables like the risk free rate, and our personal appetite for risk. I think it reasonable to take the risk free rate, and add a premium for the risk of stock ownership to that discount rate. Since my analysis will cover a 20 year span, the 20 year Treasury Bond rate of ~4.59% is appropriate as a base. So, a stock’s future cash flows must be discounted by an amount greater than 4.59%, obviously, to compensate the investor for putting their capital in the risky investment, rather than the predictable government bond. I’ll add 5% to that rate for the risks that come from stock ownership, so I’ll be discounting future cash flows from Netflix at a rate of 9.6%. Different people apply different risk rates, and I’m sure yours will be different from mine. Mileage may vary.

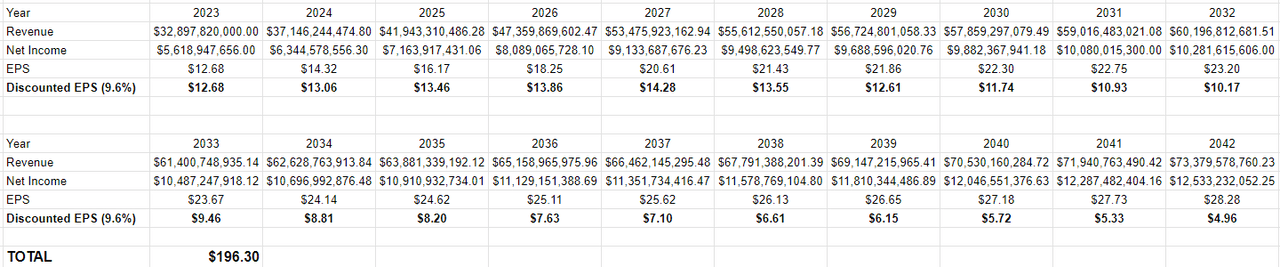

I’m going to assume that the company grows revenue over the next 5 years, at which time it becomes the cash cow that I referenced above. I’m also going to assume that the company manages to grow revenues at a CAGR of 2% over the forecasted period. I’m going to assume today’s share count remains constant. Finally, I’m going to assume that the company will manage to maintain its current profit margin of 17%, in spite of growing competition over the next 2 decades. Given all of these assumptions of a long dated future, it’s very unlikely that I’ll end up being precisely right, but I want to get a handle on what is a reasonable stock price.

Given all of the above, I come up with a net present value of future cash flows of just under $200 per share. Now, some of my assumptions may be off, and I’m obviously way below the current stock price, and my revenue estimates are below Wall Street’s future sales figures. My assumptions may be off, but I don’t think any of them are 51% off (i.e. the difference between Netflix’s current stock price, and my NPV forecast).

Author’s Netflix NPV Forecast (Author calculations)

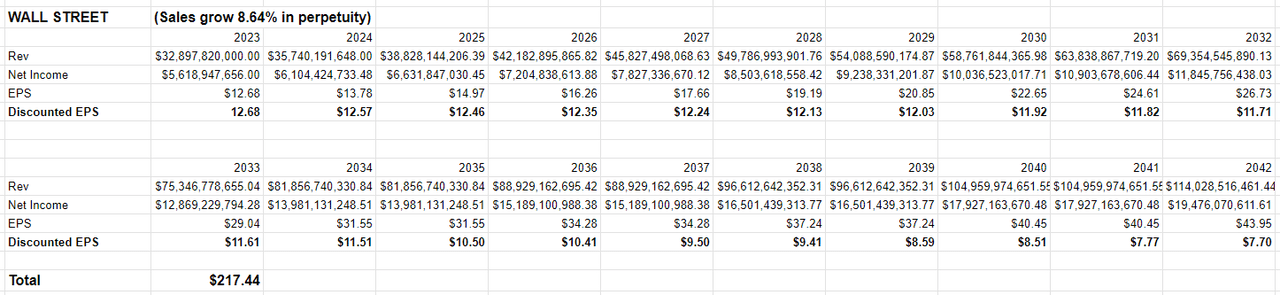

Because I’m a rather obsessive sort sometimes, I applied the same analysis assuming Wall Street’s revenue growth rate of 8.64% in perpetuity (which is a massively optimistic assumption), and came to a discounted cash flow value of $217 for the firm, per the following:

Wall Street’s Netflix NPV Forecast (Author calculations)

Given the above, I think Netflix’s current stock price is massively overvalued, even under the most optimistic assumptions provided by the good people of Wall Street. For that reason I would recommend the average investor eschew these shares. For my part, I’m going to start spending a few thousand dollars a year buying deep out of the money puts on this stock. I’ll be employing capital I can afford to lose, and I would recommend this as only a speculative trade. I am only employing capital I can afford to lose because the market may continue to drive these shares higher. My view, though, is that the higher the shares go, the greater will be my eventual payoff in puts. It may take years, but I think buying deep out of the money Netflix puts will be a great risk adjusted investment over time.

Analyst’s Disclosure: I/we have a beneficial short position in the shares of NFLX either through stock ownership, options, or other derivatives. I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it (other than from Seeking Alpha). I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.

I'm going to start buying deep out of the money puts on Netflix early next week.

Seeking Alpha’s Disclosure: Past performance is no guarantee of future results. No recommendation or advice is being given as to whether any investment is suitable for a particular investor. Any views or opinions expressed above may not reflect those of Seeking Alpha as a whole. Seeking Alpha is not a licensed securities dealer, broker or US investment adviser or investment bank. Our analysts are third party authors that include both professional investors and individual investors who may not be licensed or certified by any institute or regulatory body.