Summary:

- United Airlines has faced multiple operational incidents and accidents, raising concerns about its safety and maintenance practices.

- The airline’s aggressive growth plan, including a massive aircraft buying program, may be impacted by delivery delays and reduced capacity growth.

- United’s financial commitments for fleet acquisition and airport terminal expansion are significantly larger than competitors and will put strain on its balance sheet.

United Airlines Serves Many of the World’s Largest Cities Justin Sullivan

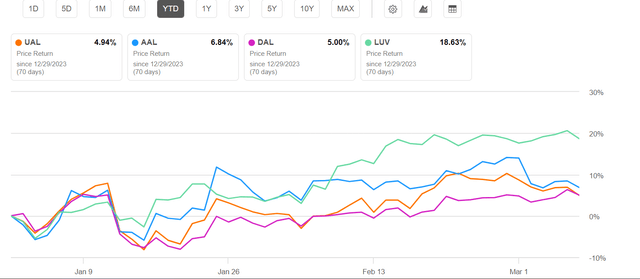

United Airlines (NASDAQ:UAL) received plenty of attention in the news during the past week, largely because of multiple operational incidents and accidents, the most recent in a turbulent year for the Chicago-based airline. Since the beginning of the year, United faced a grounding of its MAX 9 fleet as a result of the in-flight failure of an Alaska Airlines (ALK) Boeing (BA) 737-MAX 9 door plug. The resulting investigation and ongoing investigation by the NTSB resulted in the FAA telling Boeing that it will not be allowed to increase production of the MAX until the government is satisfied that Boeing has addressed the MAX safety concerns. I previously reviewed United Airlines and suggested a buy for the company. Since that time, UAL stock has appreciated 5%, the lowest for the big 4 airlines -also including American, Delta, and Southwest (LUV) – and farthest below LUV’s 18.6%. U.S. airline industry stocks fell sharply in the summer of 2023, driven primarily by macroeconomic fears and industry oversupply fears. As investors process all of this information, it is necessary to study what has taken place at United as well as consider potential changes to United Airlines’ strategies.

UAL vs big 4 8Mar2024 YTD (Seeking Alpha)

Operational Concerns or a Confluence of Coincidences?

United kicked off March with a rough week of operations

March 8, 2024 – a 22-year-old United A320 operating from San Francisco to Mexico City diverted to Los Angeles after a reported hydraulic failure.

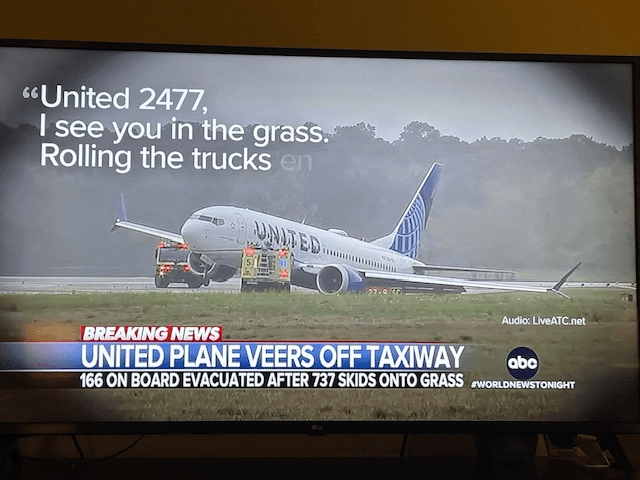

March 8, 2024 – a United 737 MAX8 slid off of the runway at Houston after landing, resulting in collapse of the landing gear

March 7, 2024 – a 22-year-old United 777-200ER lost one of the wheels on its main landing gear during takeoff from San Francisco

March 4, 2024 – one of the engines on a 21-year-old United 757-300 was shut down during a flight from Hawaii to San Francisco

March 4, 2024 – one of the engines on a 23-year-old United 737-900 experienced a stall during climbout from Houston

And during the first week of March, the NTSB provided an update on an ongoing investigation from February 2024 in which pilots on a United 737 MAX 8 reported loss of steering control after landing at Newark.

Multiple national news outlets prominently featured United’s 737 in the grass as well as at the moment when a wheel fell from one of their 777-200ERs.

United 737 off the taxiway (ABC World News Tonight 8Mar2024) United 777 losing a wheel (ABC World News Tonight 8Mar2024)

While two of the incidents involve MAX aircraft, most of the incidents involving United this week involve mature aircraft that are still well within their expected lifespan. The NTSB investigation for the Newark steering control issue involves components built by Collins Aerospace (RTX) that might not safely perform under normal airline conditions.

The 737-900 engine stall appears to involve the ingestion of foreign material (trash) into the engine; is the responsibility of airports to keep their runways and taxiways free of material that could damage aircraft engines, with airlines typically responsible for the same function on the ramps they use.

Four out of the five aircraft this week were aircraft that were older than 10 years old and have been under the control of the airline, having been through multiple rounds of airline-controlled maintenance. The 777-200ER and 757-300 are both mature airframes powered by mature engines that have proven to be reliable. While it is possible that a new problem can occur on a mature component due to metal fatigue, both of these incidents appear to raise the specter of expected failure of components or maintenance errors. Despite the recent focus on Boeing’s manufacturing and design, the vast majority of airline incidents or accidents are caused by human errors under the control of the airline. The incident involving the A320, like the 777 and 757-300 incidents involve “normal” operational issues with airliners; the question is whether the sheer number of incidents indicates systematic problems at United or whether this past week was the result of an abnormal confluence of unrelated events even if the number of those events was well-above what is typically seen at an airline the size of United. The FAA and/or NTSB are investigating each of these incidents and will connect any findings that should be connected or determine that there is no connection between these events.

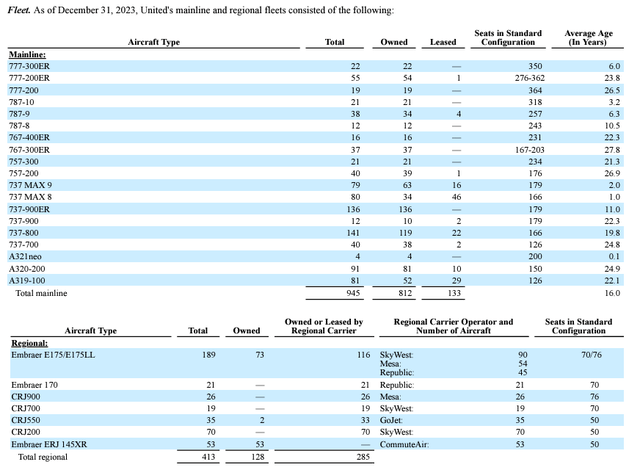

United operates almost 775 Boeing aircraft out of its fleet of nearly 950 aircraft; United is one of the largest operators of Boeing aircraft in the world. It is not surprising that a string of incidents at United would disproportionately involve Boeing aircraft.

A Pause in Pilot Hiring

United also made news this week by telling its pilots that it would halt pilot hiring for a period. United has previously said it would hire over 2000 new pilots in 2024 but would cut that rate, restarting hiring later this summer. United blamed the delivery delays of aircraft, predominantly from Boeing, for United’s need to take a pause in pilot hiring.

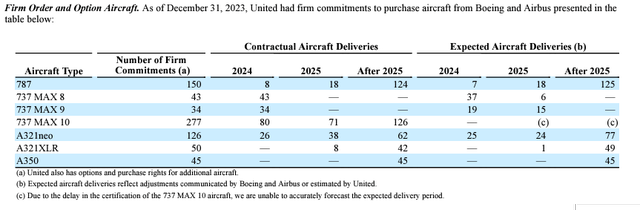

United’s Massive Growth Plan

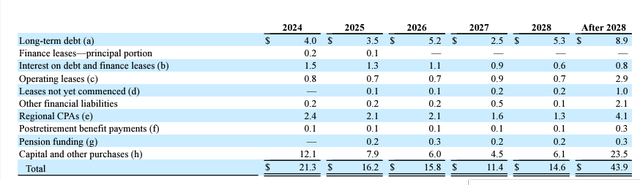

United has been trying to implement one of the largest aircraft buying programs in aviation history. As of December 31, 2023, United had firm orders for 725 new aircraft or almost 75% of its current mainline fleet. In 2024 alone, UAL committed to 191 new aircraft deliveries or 20% of its entire current fleet, but it realistically expects to receive at most 88 aircraft and perhaps less than that. For 2025, UAL has contractual obligations to receive 135 aircraft but expects to receive a maximum of 64 aircraft. The financial commitments for this massive fleet acquisition are an eye-popping $12.1 billion in 2024 and $7.9 billion in 2025, on top of the payment of $4 billion in debt payments in 2024 and $3.5 billion in 2025. UAL’s total aircraft order book is over $60 billion. For comparison, the aircraft purchase commitments for American, Delta and Southwest combined are less than for United.

UAL aircraft orders 31Dec2023 (ir.united.com) UAL fleet 31Dec2023 (ir.united.com)

United’s planned aggressive expansion is not just for airplanes. In order to accommodate all of these new aircraft, United is prepared to spend tens of billions of dollars on airport terminals. UAL’s mid-Atlantic hub is at Washington Dulles airport and the airport authority there is working on a plan to spend $6 billion on new facilities, much of which will be used by and paid for by United. At Chicago O’Hare, United’s hometown airport, the cost for expansion and renovation there has swelled to over $12 billion with the largest share of the costs to be borne by United, the largest carrier as well as by second-place American. Renovations at United’s Newark hub are expected to cost billions more, and the majority of the cost, again, will be borne by United. United has committed to or is seeking major expansion and renovation projects at all of its hub airports.

The financial commitments that United has engaged in are breathtaking in their scope and far larger in either absolute dollar amount or percentage of current revenues than for any other airline in U.S. history.

UAL financial commitments 31Dec2023 (ir.united.com)

Unraveling the Strategic Rationale

When looking at the massive financial commitments that United is making, any investor has to ask why United is spending so much more than any other airline and is that amount of spending really necessary.

First, United operates the oldest fleet among major US airlines at 16.3 years of age. While commercial aircraft routinely last beyond 20 years and all of the major airlines have individual aircraft that exceed 30 years of age, United has at least 3 fleet types that are on average more than 25 years old, encompassing over 200 aircraft. United also has dozens of aircraft in fleets that are older than 25 years old even though they are in aircraft types that are less than 20 years old on average. In total, United needs to replace more than 300 aircraft in the next 3-5 years in order to avoid having wide portions of its fleet over 30 years of age. While commercial aircraft can be maintained and kept in service much longer than previously believed, the cost of maintenance becomes more expensive as aircraft become older. In addition, older aircraft are less fuel-efficient; the tradeoff is that newer aircraft are more expensive to acquire. While United hasn’t provided indications of how many aircraft it intends to retire, its near-term indications are to use large numbers of the aircraft it has on order for growth and expansion.

Secondly, United contracts with five regional carriers to operate 413 regional aircraft for United. 155 of those aircraft are 50 seat aircraft which have the highest cost per seat mile in part because pilot and other employee salaries have increased significantly over the past two years, leaving smaller aircraft with the highest labor costs per seat. A portion of its remaining ~260 contracted regional jets are older but are 70 seat or larger regional jets. United has said that some of its order book will be used to replace those regional jets with larger mainline jets from Airbus and Boeing, but UAL’s fleet plan for 2024 envisions no reduction in the number of contracted regional jets.

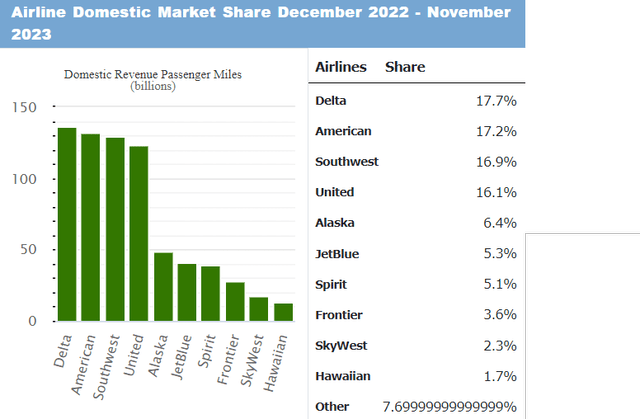

US airline domestic market share by RPM (U.S. Dept. of Transportation)

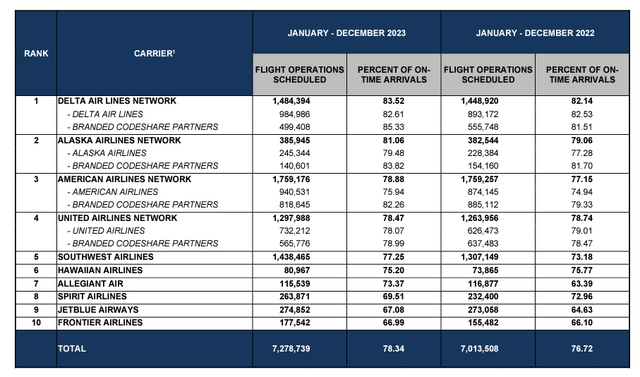

Third, and perhaps most significant, United is engaged in a massive growth plan that entails significantly increasing United’s domestic market share. According to the U.S. DOT, United ranks 4th among U.S. airlines in domestic revenue passenger mile share with 16.1%, behind first place Delta with 17.7%, American with 17.2%, and Southwest with 16.9%. United believes increasing its future profits depends on increasing its domestic market share. The following chart from the DOT shows that United operates half of the mainline (large jet vs regional jet) departures of Southwest, which leads the U.S. industry in the number of mainline flights; Delta operates the most mainline flights among the big 3, but American operates the most flights when regional carrier flights are included.

US airline operations by carrier (U.S. Dept. of Transportation)

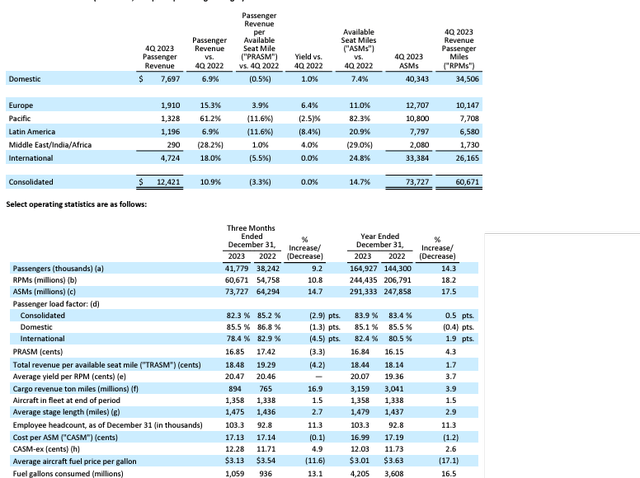

United is also attempting to grow its international market share. United proudly calls itself “America’s flag carrier” even though the United States does not have a single flag carrier; multiple U.S. airlines satisfy the requirements to wear the U.S. flag on their aircraft. United has been the largest carrier across the Pacific, generating approximately twice the amount of revenue as Delta. United surpassed Delta in 2023 transatlantic revenue, although United’s revenue was increased by service to the Arab Middle East and India, regions which Delta currently does not serve. United is the second largest U.S. carrier to Latin America based on 2023 revenue, behind American.

UAL revenue by region and statistical summary (ir.united.com)

UAL’s Middle of the Pack Financial Position

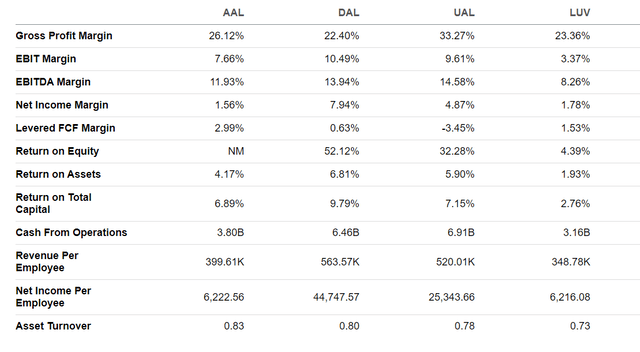

From a profitability standpoint, UAL is in a pretty decent position – for a U.S. airline. While it earned $2 billion less than Delta (DAL) in 2023, it earned more than twice as much as American (AAL) or Southwest (LUV). Many of its low cost and ultra-low cost competitors were not profitable at all. DAL’s net income margin for 2023 was 7.9%, UAL’s was 4.9% and AAL and LUV were both around 1.5%. UAL’s total operating revenues of $53.7 billion in 2023 was just over $4 billion behind DAL’s but $1 billion more than AAL. UAL’s revenue and cost metrics fall between DAL and AAL. UAL leads the U.S. passenger airlines in cargo revenues due in part to its large international route system. UAL flew the most available seat miles, 5% more than AAL and 7% more than DAL, again a reflection of UAL’s longhaul international network which does not generate revenue at the same rate as domestic-focused airlines. LUV generated “just” 170 billion seat miles. While United’s network does not generate the same revenue Delta’s does, United does have a unique position in the size of its international network.

big 4 profitability March 2024 (Seeking Alpha)

Does United need to expand at the pace it plans? That is obviously a question which United management has to convince investors of, but UAL’s financial performance is hardly of concern in the airline industry. UAL might believe a greater domestic presence will help increase its credit card revenues, which are closely tied to domestic size. Delta earns billions more in credit card and loyalty program revenue than any other airline. While the Delta relationship with American Express (in contrast to relationships with Visa at other airlines) might be part of the reason for DAL’s industry-leading non-transportation revenues, Delta’s leadership position in the domestic market certainly influences its ability to win credit card and loyalty revenue which is more tied to the domestic than international markets, where a percentage of passengers come from countries where U.S. card issuers are in a less favorable position. AAL generated more credit card revenue in 2023 than UAL.

United also has the lowest market share by metro area among the big 4 airlines. Southwest does well because of its near-monopoly airports at Chicago-Midway, Dallas Love Field, and Houston Hobby while Delta has the dominant market position at its “core 4” airports of Atlanta, Detroit, Minneapolis/St. Paul, and Salt Lake City. United has the most direct overlap with Southwest by metro area; the two compete directly against each other in Denver but have competing hubs in the Baltimore/Washington, Chicago, Houston and San Francisco Bay areas. Market share dominance has been shown to lead to the ability to sustain revenue premiums, so UAL management could be trying to increase its average fares through greater revenue share in its hubs. It is installing seatback entertainment systems on its aircraft to distinguish its service from Southwest.

United executives have talked for months about the advantage its full-service airline business model has over low cost and ultra-low cost carriers. In addition, they have called ultra-low cost carrier business models broken even as they say that UAL’s plan to increase capacity at a rate that is twice or more of expected U.S. GDP growth will be possible because United will be able to carry traffic that other airlines cannot. In reality, high labor rates and a plethora of supply chain issues have significantly harmed multiple airlines esp. within the U.S. airline industry. Low cost and ultra-low cost carriers are built to grow; that is how they keep costs down. Legacy carriers are built to generate the upper echelons of revenue and that is how they adapt to higher costs. The big 3 legacy carriers have been fortunate that longhaul international demand is strong and has helped provide a healthy source of revenue that domestic and near international focused airlines do not have. UAL’s commitment to aggressive growth seems to be driven in part by its belief that it can gain a competitive advantage over other airlines because of its international system.

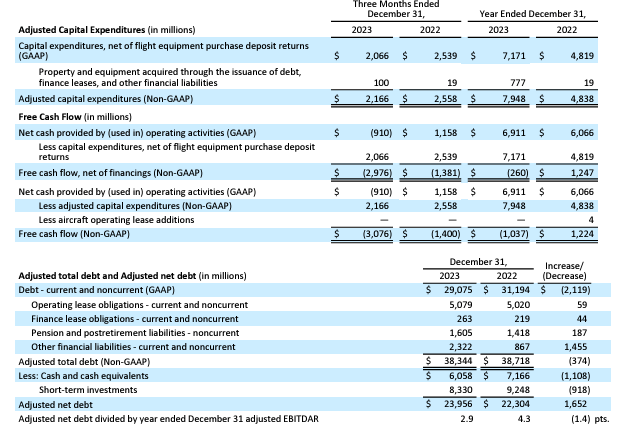

UAL 2023 capex and FCF (ir.united.com)

Near Term Reduced Growth Could be Offset by More Aircraft Orders

The reality, though, is that United’s aggressive growth plan is not likely to take place as the company laid out in the near term but could lead the company to place even more aircraft orders in order to try to recover its growth plan. UAL is the largest U.S. customer for the MAX 10, the largest version of the Boeing 737 family and had expected to receive substantial numbers of that model in 2024. Indeed, like the MAX 7, the smallest member of the MAX family, which also remains uncertified, Boeing has dozens of MAX 7s and 10s built but which cannot be delivered to airline customers. Because of the ongoing investigations by various federal government agencies into the production and quality control issues at Boeing, the chances that the MAX 10 will be delivered in the next two years is low; when the FAA gives Boeing the green light to begin increasing production and to certify new models, the MAX 7 will be certified first, which will help Southwest which has been waiting over 5 years for its first MAX 7 aircraft. United execs have said that it can no longer accurately predict when it will receive MAX 10s so is developing contingency plans.

For years, Southwest has dealt with delays in certifying the MAX 7 by changing its orders to the larger MAX 8, a move that has resulted in that airline flying larger aircraft that it wants, which has a negative impact on its ability to maximize revenue generation. Even with the conversion of some MAX 7 orders to MAX 8s, the total number of aircraft that Southwest has received has been below the numbers of aircraft in Boeing-Southwest contracts. In turn, Southwest has had to keep older aircraft in service longer, requiring costly maintenance it did not expect to have to do and the company has also not gained the fuel savings benefits from the new aircraft that it expected. From Boeing’s perspective, it continues to issue customer credits for delivery delays; it is certain that United used some of its previous customer credits from Boeing for MAX and B787 delays to augment its most recent orders for both of those models. For the airlines, though, customer credits for further purchases are increasingly unable to correct the significant disruption in those airlines’ planning processes.

Since its entire fleet is composed of the 737 in either the MAX or the previous generation of the aircraft, Southwest has no alternatives but to accept Boeing’s delays and has reduced its growth plans based on the likelihood that it not only won’t get as many 737s as it has ordered, but it also won’t receive the MAX 7 again in 2024.

Shortly after the Alaska Airlines door plug blowout that has resulted in renewed intense focus on Boeing, United publicly said it would be talking with Airbus to see if that airplane maker can help deliver aircraft that could help UAL maintain some of its growth plan. As of December 31, 2023, United had 176 A321NEO aircraft on order, 50 of which are for the longest range -XLR model which is also not yet certified due to concerns at the European aviation safety authority about the fuel tanking system on the aircraft. In addition, Airbus is experiencing delivery delays on a number of its aircraft, including for the A320NEO family, because Pratt & Whitney is having to divert significant portions of its production to correct manufacturing defects on the Geared Turbofan engine which is an option on the A320NEO family and is the engine that United chose. United is expecting to receive nearly all of its 26 A321NEO orders for 2024 during this year, but their orders for 2025 will be reduced by 21 aircraft or nearly in half.

While neither Airbus nor United have provided any updates on those discussions, it has been reported and is likely that Airbus could find additional delivery positions for United for the A321NEO family if United would firm up its order for A350s, Airbus long-range new generation aircraft, which has been pushed back by United multiple times. Given that the A350 is a competitor to the Boeing 787 and United has 150 787s on order, Airbus would love to gain part of the order for the A350. United has said that it is likely to firm up its order for A350s but for delivery later this decade and into the 2030s and use the order to replace some of its fleet of 777s. Airbus also builds the A330NEO, a new engine version of their best-selling A330 jet, which is roughly comparable to the older 777-200ER in size and the new generation 787-9 in economics on many international routes. United operates dozens of both Boeing jet models, the former of which is the least economical widebody in the U.S. carrier fleet. UAL’s Pratt & Whitney (RTX) 777-200/ER fleet was grounded due to since-corrected issues with the fan blade; United is the only U.S. airline that has a dedicated fleet of widebody aircraft in domestic configuration with the 777-200. The A330NEO is fairly low-selling and Airbus is likely to be able to deliver large numbers of the aircraft in a fairly short period; addition of large numbers of Airbus widebody aircraft to United’s order book in addition to more A321NEO family aircraft would dramatically increase stress on United’s balance sheet.

Airbus’ A320 production line is reportedly running at close to capacity and the European airframer is working to further expand production capacity. Several low-cost carriers, including in the U.S. have indicated that they are reducing their fleet spending, potentially opening up delivery positions. However, because of delivery delays on its part, Airbus is likely being required to compensate its customers and so would probably prefer to use any customer-requested order cancellations or delays to get deliveries back on track. However, if a customer is willing to pay a high enough price to accelerate deliveries, Airbus would certainly be willing to rearrange its deliveries. It is far from clear that United would be willing to spend the extra money to acquire more Airbus aircraft, and it is also not certain that Boeing would be willing to allow United to cancel orders, meaning that United’s already eye-popping capex would continue to grow. Indeed, United’s most recent statements are that it expects to reduce its planned capacity increases and accept the reality that Boeing’s delivery delays will have a significant impact throughout the global airline industry.

If United is committed to maintaining its growth plan by adding significantly more Airbus aircraft, including Airbus widebodies, UAL’s capex would soar even further and the stress on its balance sheet would continue throughout this decade and beyond.

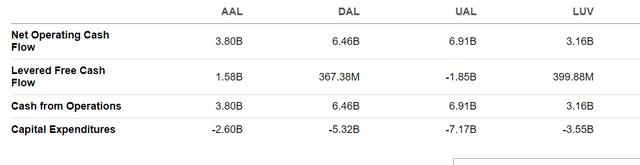

big 4 cash flow Mar2024 (Seeking Alpha)

Implications of changes to UAL’s growth plan

Investors have the potential to gain and also to be exposed to more risk as a result of United’s reduced growth rate.

First, industry capacity growth will be lower, which in general should support higher fares across the industry. United and Delta each grew their 2023 capacity by 17%. Neither Delta nor United have provided capacity guidance for 2024.

Second, market share gains that United thought it might have received by expanding while many low-cost carriers were not able to are not likely to happen. At the same time, there remains significantly uncertainty about the future of several low cost and ultra-low cost carriers in the U.S. Among the big 4, Southwest will likely be able to receive its MAX 7 aircraft and begin growing before United receives enough new aircraft to impact the competitive situation between those two airlines. American just placed an order for new aircraft that ensures it will have a modest amount of new aircraft coming online every year through the end of the decade. Delta has a comparable number of aircraft coming online as American with Delta’s fleet additions over the next five years heavily focused on long-range and large international widebody aircraft. American and Delta both have MAX 10 aircraft on order; Delta’s first MAX 10s are supposed to arrive in 2025, although it has substitution rights for other Boeing models and also has options for additional Airbus aircraft.

Third, United’s capex is certain to be reduced in 2024 by as much as 25% and perhaps more. However, in 2023, UAL spent nearly $8 billion in capex and $1 billion in negative free cash flow. Reducing spending will reduce stress on UAL’s balance sheet. However, UAL’s fleet spending is not likely to be reduced in total, which means they will simply be shifting spending out two years or more and still face very heavy spending for most of the latter half of this decade. If UAL adds significantly more orders, including potentially higher priced Airbus aircraft, its capex and debt load would soar.

Finally, UAL’s growth plan has many components and, while some pieces will be delayed, the timing of others will not change. United’s fleet will continue to age, which means that the final years of life in many of its aircraft cannot be used for growth but rather more of their new aircraft deliveries will have to be used for replacement. At the same time, some of their terminal expansions could be ready earlier than they might otherwise be needed, which will increase costs before they are needed. From a personnel standpoint, stability of other players in the industry could mean that United’s ability to recruit new employees could be reduced.

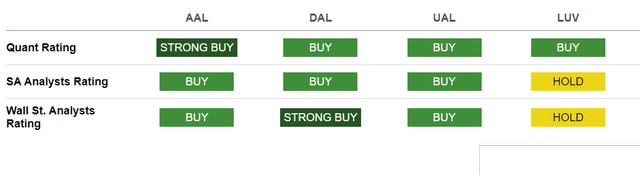

big 4 ratings March 2024 (Seeking Alpha)

Boeing’s delays on the MAX, and particularly the MAX 10, will push United Airlines’ growth plan back further. If the company succeeds in ordering large numbers of additional Airbus aircraft in order to preserve its growth plan, its capex will increase even further. The uncertainty United faces with its fleet plan and the results it will have on its very publicly discussed growth plans make it prudent to reduce expectation that UAL will outperform the industry.

Even without clarification regarding UAL’s growth plans, UAL stock gains have underperformed the big 4 so far in 2024, particularly of LUV which is dramatically lower than its historical levels. Southwest has one of the industry’s cleanest balance sheets and is one of several more attractive buys in an industry that is coping with Boeing’s production issues. A HOLD rating on UAL stock is now appropriate.

Analyst’s Disclosure: I/we have no stock, option or similar derivative position in any of the companies mentioned, and no plans to initiate any such positions within the next 72 hours. I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it (other than from Seeking Alpha). I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.

Seeking Alpha’s Disclosure: Past performance is no guarantee of future results. No recommendation or advice is being given as to whether any investment is suitable for a particular investor. Any views or opinions expressed above may not reflect those of Seeking Alpha as a whole. Seeking Alpha is not a licensed securities dealer, broker or US investment adviser or investment bank. Our analysts are third party authors that include both professional investors and individual investors who may not be licensed or certified by any institute or regulatory body.