Summary:

- Apple Inc. and Tesla, Inc. may both be industry leaders, but Warren Buffett has chosen to invest in one and avoid the other. Here’s why.

- While Apple has been reducing its invested capital, Tesla has been expanding it by 25% CAGR over the past 5 years.

- Buffett prefers to avoid “difficult” investments and appears hesitant to invest in Tesla due to its high capital costs, huge risks, and expensive valuation.

- For Buffett to invest in Tesla, the company would need to consistently produce good returns on capital, become cheaper, and demonstrate a sustainable moat in its industry.

Paul Morigi

The Warren Buffett Approach: How ROIC Shapes Investment Decisions

Warren Buffett’s investment philosophy centers around the concept of Return on Invested Capital (“ROIC”). In his 2007 shareholder letter, he elucidated this approach through an example from his investment in See’s Candy. The crux of the matter is that a company that requires minimal capital to operate, but generates substantial profits, will invariably produce excellent returns for its shareholders over the long haul. In the words of Charlie Munger, Buffett’s trusted partner and Berkshire Hathaway Inc. vice chairman:

“It’s challenging for a stock to outperform the underlying business over the long term. If a business earns a 6% return on capital over four decades, you’ll end up with a comparable return even if you purchased the stock at a significant discount. On the other hand, if a business generates an 18% return on capital over 20 or 30 years, then buying it at a seemingly exorbitant price will still yield excellent results. Therefore, the key is to invest in superior businesses, which benefit from momentum effects and scale advantages.”

The Remarkable ROIC of Apple: A Testament to its Unique Business Model

Apple has consistently generated returns on capital that have surpassed 20% since 2010. As of the latest figures, these returns stand at a remarkable 50%, with the past five years averaging around 31%. This impressive performance has translated into significant gains for the stock, which has surged from $36 in 2017 to $170 in May 2023, delivering a CAGR of 31% – a strikingly similar figure to the past five years’ ROIC. Apple’s enviable position stems from its ability to operate its business with minimal capital requirements, leading to a tangible book value that is dwarfed by the vast profits it generates – a staggering $55 billion, in fact. Furthermore, with only $100 billion in debt, the firm’s invested capital stands at approximately $155 billion, a testament to the lean yet highly profitable nature of its operations.

This unique combination of razor-thin capital expenditures and robust profitability has resulted in exceptional outcomes for investors. As Charlie Munger has aptly noted, Apple’s long-term returns for investors are quite similar to its ROIC figures, meaning that even buying in at a higher multiple could still result in fine outcomes. Remarkably, since 2017, Apple has managed to decrease its invested capital by approximately $50 billion, all the while increasing net income by the same amount. This outcome translates into excess cash that can be distributed to shareholders, primarily through buybacks. Additionally, the company has shifted its capital structure from equity-financed to debt-financed, a far more cost-effective form of liability, which translates into even more value for shareholders.

Berkshire Hathaway’s Best Investment Ever? Apple’s High ROIC and Low Multiple Make a Winning Combination

Berkshire Hathaway identified Apple’s outstanding ROIC performance as far back as 2016, making it one of the company’s most successful investments to date. Despite the premium ROIC that Apple has delivered over the past few decades, one might assume that the multiple an investor would have had to pay was prohibitively high. However, a closer look at Apple’s valuation at the time reveals just how undervalued it was. In 2016, the EV/EBITDA ratio for Apple was just 5, while the average for the S&P 500 (SP500) was well above 10 during the same period. As a result, Berkshire was able to acquire a large company that generated exceptional ROIC at a remarkably cheap multiple, delivering significant value to its shareholders.

EV/EBITDA Multiplier Apple (SA)

Tesla’s Impressive Incremental ROIC Outshines Apple’s Performance:

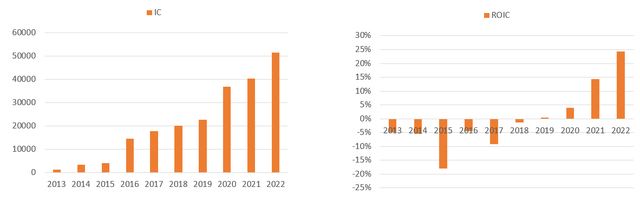

Tesla’s (NASDAQ:TSLA) ROIC has only recently moved into positive territory, increasing from 4% in 2020 to 24% in 2022. However, for Buffett and Munger, who emphasize consistency in earnings, Tesla’s lack of a track record of consistently producing high ROIC over the past five years alone would make it a non-starter as an investment. In their shareholder letters over the past 50 years, they have emphasized the importance of consistent earnings as a prerequisite for investment consideration.

One could argue that Tesla is sitting on a large cash balance of over $20 billion that could be returned to investors, boosting its ROIC considerably to a figure above 40%. However, Tesla seems intent on retaining the cash on its balance sheet, which, coupled with its almost zero debt, is earmarked for future capital investments or to sustain an economic slowdown.

ROIC is a snapshot of last year’s earnings (before interest payments) divided by the invested capital (the assets required to run the business). By focusing on return on incremental invested capital, however, it becomes apparent that Tesla’s returns are very high. The delta in invested capital from 2021 to 2022 was $11 billion, while operating profits after tax (NOPAT) grew by $6 billion, resulting in an impressive incremental return on invested capital of 55%, which is above that of Apple’s ROIC.

Invested Capital and Return on Invested Capital Tesla (SA & Author)

It is worth noting the divergent trends in the directionality of invested capital at Apple and Tesla. While Apple has steadily decreased its invested capital in recent years, resulting in favorable effects for shareholders, it also signals that the company’s total addressable markets (“TAM”) are saturated. In other words, Apple may have reached the limit of its growth potential in existing business ventures and is not expanding into new ventures requiring new capital investments.

In contrast, Tesla has been expanding its invested capital at an impressive compound annual growth rate of 25% over the past five years. Management guidance suggests that this trend will not be slowing down anytime soon, with continued investments in new product lines and capacity. While this implies that cash may not be paid out to investors in the near future, it lays the groundwork for high invested capital and high ROIC if Tesla’s plans come to fruition. Ultimately, cash payouts are a fundamental basis for any company valuation, and Tesla’s growth trajectory may position it well for long-term success.

Why Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger Won’t Invest in Tesla: A Closer Look

Munger and Buffett’s rationale for not investing in Tesla is multifold. Firstly, the duo has always preferred to stay away from investments that pose a significant challenge. Tesla, with its high capital costs and inherent risks, has been placed in the “too difficult” basket by the seasoned investors (as seen in this video: “Warren Buffett: I know where Apple is going to be in five or ten years, but not car companies”). Secondly, Tesla’s EV/EBITDA ratio of 31, is too high for the Berkshire investment philosophy. It is noteworthy that Berkshire started investing in Apple only when it had a ratio of 5, indicating that the duo considers higher multiples to be accompanied by bigger risks.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, Warren has repeatedly emphasized the need for consistency in profitability in his shareholder letters over the past five decades. Berkshire only invests in companies that have a consistent record of profitability over at least five years, and Tesla’s recent foray into the profitable territory does not meet the historic criteria set by the Berkshire duo.

To change this perception, Tesla would have to address all three issues to prove to Munger and Buffett that it has a sustainable moat in its industry. It needs to consistently demonstrate good returns on capital and fend off competition in the industry. As Warren puts it, he looks for “economic castles protected by unbreachable ‘moats’.” Tesla would also need to become cheaper, as an EV/EBITDA ratio of 31 is simply too high for Berkshire’s investment philosophy. Warren is known for his discipline and patience over the past five decades, which have allowed Berkshire to outperform the market. He would prefer to wait until the valuations gets cheaper or continue searching for other investment opportunities.

Tesla, Inc.’s considerable market capitalization ensures that it remains on Berkshire’s radar, and with a substantial cash reserve, Berkshire is always seeking opportunities to deploy its funds. However, for an investment to be truly significant, Berkshire must focus on companies with mega-cap status. In the case of Tesla, should the electric vehicle giant exhibit consistent high return on invested capital ROIC coupled with a more moderate multiple, it could be a compelling investment opportunity for Berkshire. However, it is important to emphasize that this investment philosophy applies not only to Tesla, Inc. but to every other company that Berkshire evaluates.

Analyst’s Disclosure: I/we have a beneficial long position in the shares of TSLA either through stock ownership, options, or other derivatives. I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it (other than from Seeking Alpha). I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.

Seeking Alpha’s Disclosure: Past performance is no guarantee of future results. No recommendation or advice is being given as to whether any investment is suitable for a particular investor. Any views or opinions expressed above may not reflect those of Seeking Alpha as a whole. Seeking Alpha is not a licensed securities dealer, broker or US investment adviser or investment bank. Our analysts are third party authors that include both professional investors and individual investors who may not be licensed or certified by any institute or regulatory body.