Summary:

- Merck is a “big pharma” powerhouse with a $20bn per annum selling drug in Keytruda.

- The company has different divisions and has its most ambitious plans are centered around Oncology, Cardiovascular and Vaccines – its traditional strength.

- In this post I model product-by-product sales projections to 2030, and use discounted cash flow analysis to judge at what price the share price should trade.

- My conclusion is that the patent expiry of Keytruda in 2028 weighs a little too heavily on the company, whose pipeline is large and diverse but lacking in star quality.

- As such I’m not expecting a strong share price performance from Merck in 2023, and can see its stock slipping below $100 per share.

Marko Georgiev

Investment Overview

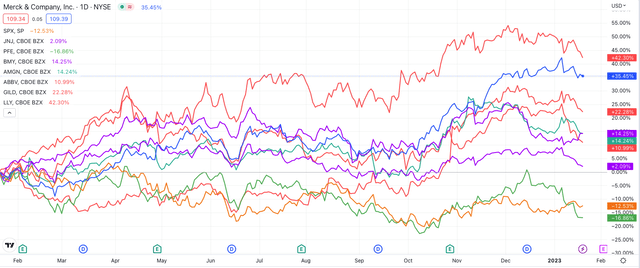

The large pharmaceutical sector had a strong year in 2022, as we can see in the chart below:

Share Price performance of “Big 8” US Pharmas versus S&P 500 – past 12 months (TradingView)

Out of what I tend to refer to as the “Big 8” US Pharmas – by order of market cap – Johnson & Johnson (JNJ), Eli Lilly (NYSE:LLY), AbbVie (ABBV), Pfizer (PFE), Merck & Co (NYSE:MRK), Bristol Myers Squibb (BMY), Amgen (AMGN), and Gilead Sciences (NASDAQ:GILD), only Pfizer under-performed the S&P 500 with the average return being ~15%, vs. the S&P 500’s 12.5% decline.

These large pharmas are all profitable, driving average net profit margins >20% in 2021, with the average price to sales (“P/S”) ratio being 5.6x and average price to earnings (“P/E”) ratio being 26x. All 8 also pay dividends, with an average yield of ~2.8%.

Given that much of 2022 was spent under a COVID cloud, with interest rates and inflation rampant, and with most other sectors of the stock market underperforming badly, we can conclude that 2022 was an exceptional year for big pharma, and especially so for Merck & Co – the subject of this post.

New Jersey headquartered Merck’s stock delivered a 35% gain for shareholders in 2022, which was only bettered by Eli Lilly stock’s 36% gain, and in fact across the past five years Merck and Lilly have been the outstanding performers, with Merck stock rising in value by 86%, and Lilly’s by a staggering 300%. The next best performing stock belongs to Amgen, which is +34%.

Merck’s success has been based around Keytruda, its all-conquering immune checkpoint inhibitor (“ICI”) that blocks the pathway of Programmed death-1, or PD-1, a type of receptor expressed on the surface of T-cells that can tell the immune system not to attack cancer cells.

Keytruda has been approved to treat melanoma, non-small cell lung cancer (“NSCLC’), head and neck cancer, Hodgkin’s Lymphoma, B-cell lymphomas, bladder cancer, colon or rectal cancer, and types of stomach, throat, kidney, liver and breast cancers.

Revenues earned by Merck from Keytruda in 2019, 2020, and 2021 were respectively $11bn, $14bn, and $17bn, and in 2022, when Merck announces full-year earnings in a few weeks’ time, it is likely the drug will pass $20bn in annual sales.

The second most important element of Merck’s business is its vaccine division, which generated $9.7bn of revenues in 2021, and likely generated ~$11bn in 2022. Led by Gardasil – a vaccine against Human Papilloma Virus (“HPV”) that will generate ~$7bn revenues in 2022, and ProQuad / Varivax – indicated for measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella, and driving >$2bn revenues per annum, this division accounts for ~18% of all Merck’s revenues – Keytruda alone accounts for 34%.

As I wrote in my last piece of coverage on Merck for Seeking Alpha back in July:

Merck has several other divisions – Hospital Acute Care, which accounted for 6% of revenues in 2021, Immunology, 2.3% of revenues, Neuroscience, 0.7%, Cardiovascular, 1.2%, Diabetes, 11%, Animal Health, 11.4%, and finally Virology, which includes the COVID-19 antiviral Molnupiravir, now branded as Lagevrio, which is expected to make sales of $5 – $5.5bn this year.

In that last note I provided product by product revenue forecasting for all of Merck’s portfolio to 2030, then fed it through a model forward income statement, and then applied discounted cash flow analysis to try to establish if Merck stock was over or undervalued.

My conclusion was that Merck stock ought to be worth ~$107, which allowed for ~20% upside based on Merck’s stock price back in July. Fast forward six months however and Merck’s stock price has roared past that figure, hitting a peak of $115 in the first week of January this year, which values the company at $276bn.

Merck may have caught the market by surprise with a bull run that saw its stock gain 22% in a little under three months, but there are some early warning signs that 2023 may not be such a strong year for the company’s stock price. As we can see from the chart above all of the “Big 8” US Pharmas have seen valuations fall in January, ahead of the full year 2022 reporting season.

Merck stock may be being punished for a failure to complete an acquisition of oncology partner Seagen (SGEN) last year – a deal looked likely in July but it seems the two companies failed to agree on a fair price.

Seagen is an antibody drug conjugate specialist that has co-developed Ladiratuzumab Vedotin – currently in Phase 2 studies in patients with breast cancer as a combo therapy with Keytruda, as well as relapsed and refractory metastatic breast cancer and solid tumors – alongside Merck, and also has three commercialized assets – Adcetris, indicated for Hodgkin Lymphoma, Padcev for bladder cancer, Tukysa for breast cancer, and newly approved Tivdak for cervical cancer.

These assets generated $1.4bn of revenues in 2021, and perhaps as much as $1.7bn in 2022. Seagen is currently valued at $24bn market cap, although Merck would likely have to pay a substantial premium – perhaps as much as $40bn – to complete a deal, and management appears to have balked at the asking price.

Speaking and presenting at the JPMorgan Healthcare conference which took place last week, Merck’s new CEO Robert Davis – who succeeded the retiring Kenneth C. Frazier in October last year after 30 years at the helm – was keen to stress that Merck had spent $36.5bn on business development over the past five years, although that has not necessarily translated into new revenue streams and the company remains heavily reliant on Keytruda, which will lose its patent exclusivity in 2028, with sales likely to decline at a rate of ~20% per annum after that.

In the light of the Seagen retreat and with Keytruda’s loss of exclusivity (“LOE”) looming, I have set out to revise my forecasts from July and unfortunately my outlook for Merck is less optimistic than it was back in July, partly due to the company’s rapidly climbing share price, but also partly due to what I perceive as a lack of “star quality” in the company’s pipeline.

Comparing Merck to Eli Lilly, for example, Lilly’s Tirzepatide – already approved to treat Type 2 diabetes, and likely to be approved to treat weight loss this year – has been pegged for sales of anything up to $50bn per annum (see my recent detailed note on Lilly) and likely justifies the hype around the pharma and its soaring share price.

As I’ll show through the rest of this post, although Merck has promised to return to growth rapidly after the LOE of Keytruda, that may not happen this decade, while the decline in sales of Lagevrio is likely to substantially decrease Merck’s revenues in 2023.

As such, I’m less optimistic about Merck’s prospects of growing its share price in 2023. The company still pays a generous dividend yielding 2.7% at the time of writing, and you can still make case for the company as a long-term buy and hold opportunity, but as I will show below, I would not rank Merck stock amongst the Top 5 Big Pharma stocks to hold in 2023.

Merck By Divisions – Oncology Diversifying But Keytruda LOE Looks Problematic

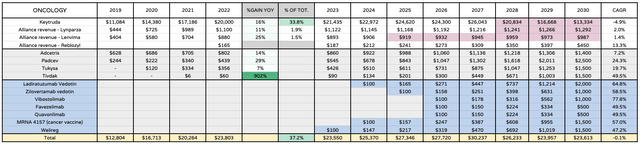

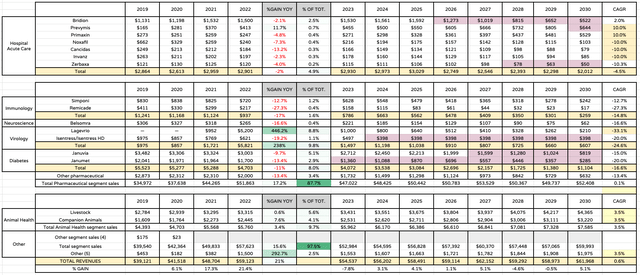

Merck Oncology Product and Pipeline projected revenues to 2030 (My table and assumptions)

Keytruda has been a wonderful drug that has had tremendous success treating patients with solid tumor cancers, and it may not be an exaggeration to say that hundreds of biotechs are testing their lead assets in combination with Keytruda in the hope of finding an extra efficacy edge and gaining commercial approval.

As we can see in the table above I’m forecasting for the drug’s revenues to exceed $20bn in 2022, and that may be a conservative estimate given that after 9m of 2022, sales were up 28% year-on-year. I calculate FY22 revenues by taking the 9m sales figure and increasing it by the average of the three previous quarter’s revenues.

Given that Merck is forecasting for $58.5bn – $59bn revenues in 2023, I have had to trim sales of most of Merck’s best-selling assets to massage the revenue figure down to meet that estimate, which may suggest that Q422 revenues will be a little underwhelming compared to an otherwise buoyant 2022.

Given that Keytruda sales are forecast by analysts to exceed $24bn by 2026, I have increased revenues by ~7% per annum between 2022 and 2027 so that peak sales in 2027 exceed $26bn, before reducing sales by 20% per annum thereafter to reflect the impact of the LOE.

In my previous forecasts in July I assumed that Seagen would be acquired and therefore added in revenue projections for its portfolio of drugs, including newly approved Tivdak. This time, however, I have “greyed” these projections out and not included them in the oncology division revenues calculation.

What that means is that Merck may find it very challenging – by my calculations at least – to grow oncology revenues this decade.

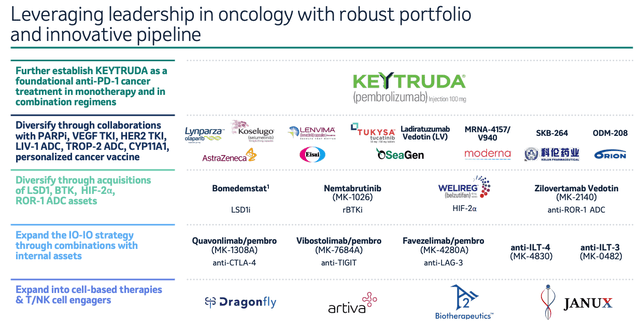

Merck’s leadership in oncology (JP Morgan presentation)

As we can see from a slide presented by Merck at the JPMorgan Healthcare conference earlier this month, the company is not short of development partners or pipeline assets, although unlike rival pharma AbbVie, for example, which has moved very quickly to approve drugs that can offset the declining sales of its $20bn per annum selling Humira, Merck has no obvious Keytruda replacement.

The pharma industry has struggled to make a success of the antibody drug conjugate class of drugs to date, despite the billions spent on R&D and M&A – another reason why Merck may have been reluctant to pursue a deal for Seagen – and although, as I have shown above, we can expect multiple new drug approvals, none have the mega-blockbuster potential that Merck desires.

I discussed each of the new drugs set for approval in my last note, except for MRNA-4157, which I will come to shortly. Welireg is already approved to treat Hippel-Lindau (“VHL”) disease, and could expand its label into kidney and as a combo with Keytruda. Vibostolimab uses an anti-TIGIT approach, Favezelimab is another immuno-oncology drug that is anti-LAG-3, and Quavonlimabis anti-CTLA4 – another popular target.

None of the latter three are guaranteed to be approved, with the jury still out on TIGIT, as a viable druggable target whilst Merck is behind the curve compared to rival Pharmas with its LAG-3 and CTLA-4 programs.

An area of genuine interest for Merck is its partnership with MRNA giant and COVID vaccine developer Moderna (MRNA), to develop what’s called a personalised cancer vaccine (“PCV”). The idea is that injecting patients with these vaccines can teach the immune system to recognise circulating tumor DNA and attack it, which can help to augment the effect of an ICI such as Keytruda.

Although Merck paid $250m to Moderna to continue the partnership last year, and the two companies posted some encouraging Phase 2 data showing that the addition of MRNA-4157 cut the risk of death or recurrence of melanoma (skin cancer) by 44%, if we’re being very picky – as we must in the field of drug development – the companies used some favourable trial measures to achieve a clinically significant result, and with melanoma being one of easier to treat cancers, there’s no guarantee yet that a genuine breakthrough has yet been made. That is why I have only assigned MRNA-4157 $1.5bn of peak sales by 2030.

To summarize Merck’s oncology division – it is the company’s largest, despite there being only three approved assets, two of which are partnered – Lynparza, a PARP inhibitor indicated for ovarian cancer marketed and sold by AstraZeneca (AZN), who pay royalties to Merck under a licensing deal, and Lenvima, a thyroid cancer drug marketed and sold by Japanese Pharma Eisai, who also pay royalties to Merck.

It’s possible that Lenvima will lose patent protection as early as 2025 (I have shaded red where I anticipate LOE and reduced revenues by 20% per annum in subsequent years), although I have given Merck the benefit of the doubt and continued to grow revenues for both partnered drugs.

The issue I see is that there no standout asset capable of driving the mega-blockbuster sales that Keytruda has done for many years, and therefore, despite multiple approval shots, I am forecasting for flat growth.

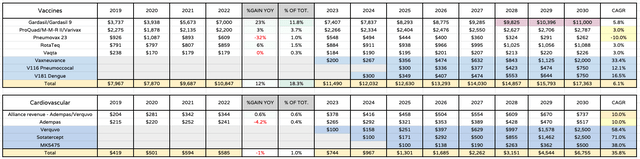

Vaccines and Cardiovascular – Areas of Genuine Promise, With Some Flaws

Merck Vaccine and Cardiovascular Division revenue forecasts to 2030 (My table and assumptions)

As we can see above, despite a forecast patent expiry (according to Merck’s 2021 10K submission) for Gardasil in 2028, Merck management is confident the vaccine can double sales between 2022 and 2030 and deliver >$11bn of revenues in the latter year, based on growth of demand and ability to supply larger volumes.

The same growth may not apply to Proquad, Rotateq or Vaqta, however, which make up the current pipeline and the pipeline assets are an unknown quantity at present. Vaxneuvance, for example, will compete against some entrenched competition in e.g. Pfizer’s Prevnar, without having established its superiority.

CEO Davis told the audience at the JPM fireside chat that:

this is a market roughly $7 billion in 2020. It’s probably going to be $13 billion, $14 billion by 2030.

That claim is supported by market forecasts I have found online, which is why I’m forecasting peak sales of $2bn by 2030, although analysts have been reluctant to forecast >$1bn.

There are two more vaccines in late stage clinical studies that could add value to this division – namely V116, a “next-generation” pneumococcal vaccine candidate, and V181 indicated for Dengue disease. I’m reluctant to forecast for peak sales of >$750m each, given the options already available in pneumococcal, and uncertain market dynamics for Dengue.

Turning to cardiovascular, Merck believes this can be a $10bn per annum franchise, but I have some reservations. Verquvo, developed in collaboration with German Pharma Bayer, is approved to treat chronic heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (“HFrEF”), but there is scepticism about whether the drug, which Merck eventually acquired from Bayer for just $1bn, can compete against the likes of Novartis’ (NVS) Entresto and AstraZeneca’s Farxiga, which have a first mover advantage in this space.

Nevertheless, I’m forecasting for $2.5bn in peak Verquvo revenues, and >$1.2bn in Adempas collaboration revenues, although that still leaves me a long way short of a $10bn per annum revenue cardiovascular division.

Merck’s other push in cardiovascular is to establish a franchise in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension (“PAH”) with Sotatercept. At the JPM conference Merck’s new head of Research Dean Li commented that:

Sotatercept has the potential to transform the treatment of patients with PAH. I have treated patients with PAH. This is a rapidly progressing and fatal disease. The positive results for the Phase III STELLAR trial demonstrated a profound impact in the six-minute walk distance. Equally important is that it met eight of the nine secondary endpoints such as time to clinical worsening.

We target filing for this with regulatory agencies in the first quarter of 2023.

Sotatercept was the prized asset acquired by Merck as part of its $11.5 takeover of Acceleron and analysts have predicted that the drug could earn as much as $4bn in peak revenues, after it impressed in a Phase 3 trial, meeting its primary endpoint by significantly extending how far patients with PAH could walk in six minutes.

There’s a caveat here however in the shape of United Therapeutics (UTHR), which has a monopolistic control of the PAH market and a reputation for fighting tooth and nail to maintain its dominance. Merck could not have chosen a tougher competitor to go up against, and even with a best-in-class profile, it will not be easy to take market share away from the incumbent.

Merck in fact has two other drugs in its pipeline I have not included in this forecasting – MK-0616, an oral PCSK9 inhibitor as well as a Factor XI inhibitor. In time, Merck believes its cardiovascular division will consist of eight approved drugs generating $10bn per annum, but I’m modeling or only $6.7bn, hedging against the risk of drugs failing to make it to market on safety of efficacy grounds, plus the strength of the market incumbent.

To summarize, Merck has a strong vaccine division that I am forecasting to nearly double revenues in eight years, and a very promising, if unproven cardiovascular division that may be capable of outperforming my expectations set out here. These two divisions, plus oncology, carry a significant burden of expectation, however, and the competitive threats are significant.

Hospital Acute Care, Immunology, Neuroscience etc. – Divisions That Seem To Be Treading Water At Best

Merck smaller divisions revenue projections to 2030 (My table and assumptions)

If Oncology, Cardiovascular and Vaccines are Merck’s core focus as it looks to offset the patent expiry of Keytruda, then it’s hard to get too excited about Merck’s many other divisions.

As you can see from the table above, sales performance of assets within the Hospital Acute Care, immunology, virology, neuroscience and diabetes divisions have trended significantly downwards through 2022 – other than Lagevrio, sales of which will likely decline by several billion dollars in 2023.

With the near-term approval pipeline looking thin across these divisions, the outlook here is quite troubling. Merck disposed of its Women’s Health, Biosimilars and legacy drugs divisions by spinning them out into a new entity, Organon (OGN), in 2020, but perhaps the company now wishes it had exited other businesses as well.

The Animal Health business continues to perform adequately to well, and there has been a sizeable uptick in “Other” revenues, but overall I’m struggling to find reasons to be cheerful about these divisions whose best days may now be behind them.

Income Statement, DCF Analysis and Price Target

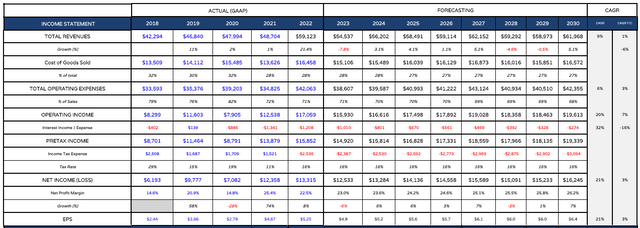

Merck forward income statements to 2030 (my table and assumptions)

Taking the sum of revenues from all divisions that I have forecasted, I plug these figures into a forward income statement.

As shown above, I have massaged down operating expenses as a percentage of total revenues from 71% in 2022 to 68% in 2030, reflecting management’s optimism expressed at JPM that margins are expanding.

Most businesses would be delighted to be generating >$15bn of net income, as I forecast Merck will do by 2024, accelerating to >$16bn by 2030. Merck’s debt is not excessive – by big pharma standards at least – standing at ~$28bn as of Q322 – and interest payments ought to decline over time – unless Merck does complete a takeover of Seagen. Either way, the debt is not too problematic for a company of Merck’s size, and make no mistake, this is a strong business – just perhaps not quite as strong as the market believes.

Merck – price target calculated using DCF analysis (my table and assumptions)

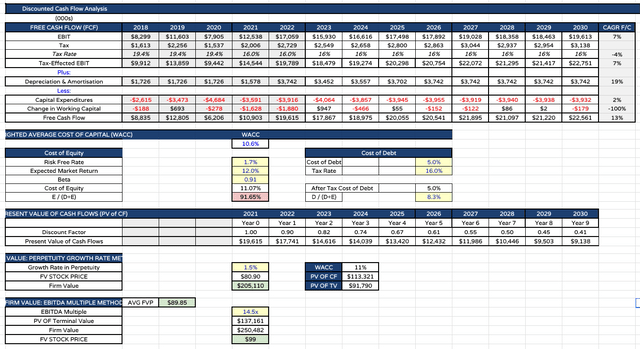

Finally, I can present the basic discounted cash flow analysis that helps me achieve my price target.

Using a Weighted Average Cost of Capital (“WACC”) of 11%, and applying discount factors, I achieve a price target of only $81 using the perpetuity growth method, and a higher value of $99 using the EBITDA multiple method.

That leaves me with an average of $90, which represents a discount of nearly 20% to Merck stock’s current traded price.

Conclusion – Not All Doom and Gloom But Sufficient FUD To Make Merck A Stock To Watch and Not Buy For The Time Being

That completes my analysis of Merck based on product by product forward projections, and ultimately, although the price target of $90 may be a touch on the low side, it reflects the fact that Merck may be in a position where it does not have the ability to replenish its pipeline with assets of sufficient strength to offset the Keytruda LOE long term.

Doubtless, Merck’s R&D efforts will be in overdrive and nothing is guaranteed in the pharmaceutical industry – but comparing my forecasts with those I have completed for the other seven “Big US Pharmas,” my conclusion is that Merck would not be amongst my Top 5 picks for 2023.

There’s not necessarily any need for Merck shareholders to panic – Merck remains an exceptionally strong company paying a handsome dividend – but the price correction experienced in 2023 to date may be a sign that in terms of share price upside, this may not be Merck’s year, as the scale of the rebuilding job at the company, under new management and with its most important asset in its final years of exclusivity, looks a little larger than its rivals, based on my analysis.

Disclosure: I/we have a beneficial long position in the shares of GILD, BMY, ABBV either through stock ownership, options, or other derivatives. I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it (other than from Seeking Alpha). I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.

If you like what you have just read and want to receive at least 4 exclusive stock tips every week focused on Pharma, Biotech and Healthcare, then join me at my marketplace channel, Haggerston BioHealth. Invest alongside the model portfolio or simply access the investment bank-grade financial models and research. I hope to see you there.