Summary:

- The hot topic of the recent memory downturn has been Samsung’s unwillingness to cut CapEx and fall in line with the oligopoly.

- But Samsung’s higher CapEx won’t help it achieve the goals of gaining market share and pushing others out.

- Samsung is not the technology leader, has poor yields, and has lost significant market share since being the producer proud of going to EUV first.

- Its choice to dive head first into EUV has lost it the crown, and the only way for it to survive is for it to maintain CapEx, but it will have little effect on gaining market share.

Devonyu/iStock via Getty Images

The most prominent topic of the current memory downturn has been Samsung (OTCPK:SSNNF)(OTCPK:SSNLF) and its unabashed plans to continue driving CapEx in the face of plummeting demand and profits. Higher CapEx is perceived as ramping supply, and when demand falls below supply, adding more to the supply end of the equation only makes the situation worse. The biggest loser in this situation is Micron (NASDAQ:MU), as it confirms the oligopoly won’t stand shoulder-to-shoulder, leading to lower prices on the market. This translates to negative growth and a more extended memory downcycle. But that’s the perception. The problem is the tactics Samsung appears to be taking are being drawn out of context by analysts and investors, especially those in the financial media. Ultimately, Samsung has no choice but to continue spending money, not to destroy its competitors, but to survive.

That’s right; I said survive. The behemoth that is Samsung is not the all-powerful Samsung it was over a decade ago when it last used these cutthroat tactics.

So when I watch, hear, and read pundits describing the situation in the memory industry regarding the company, it makes me question their angle. While I don’t blame them for jumping to conclusions, as the most straightforward conclusion, in this case, stokes fear, it doesn’t take more than a minute to think through the process Samsung is embarking on.

The thought process isn’t complicated and doesn’t require many assumptions – very few, in fact. It’s why I find it difficult to understand why more analysts don’t realize the truth of Samsung taking the path of not cutting CapEx. But it requires looking at the entire picture, not just the actions or reactions of one company.

The Theory Behind Flooding The Memory Market

Taking this one step at a time, I’ll first explain why the move by Samsung appears to be a backstab to the “Big 3” and why the media is focused on this.

In decades gone by, a tactic has been used to take DRAM market share during depressing memory industry times by pushing other producers out of the market (by forcing them into bankruptcy). In these “olden” times, there were well over a dozen DRAM producers. Samsung was king of the hill and had the claim to market share leader. It also had the best technology at scale.

Because of its leading cost structure, Samsung was able to flood the market with its chips, pushing prices lower. This lower pricing caused smaller, less financially solid DRAM producers to go bankrupt. But because Samsung had leading technology, a relatively strong balance sheet, and led in market share, it could afford to sell chips at lower prices and not undercut itself.

To illustrate, I’ll use some example numbers and convey basic but accurate fundamental workings of the industry during this type of scenario.

Let’s say the market price of a specific DRAM chip sold for $2 at the time. On the other side of the margin, the cost to produce the chip is derived from the technology used (how many bits per wafer) and production efficiency at the producer. In this example, Samsung could produce it for $1.50 per chip. But other producers could only make it for $1.90. By ramping up the supply of this chip and flooding the market, Samsung would further upset the balance of the supply and demand dynamic and push the market price down to $1.60. The market price for Samsung is still above its break-even, but the producers with inferior nodes (technology) are now selling for a loss or not selling at all because they’re bailing a sinking ship.

Eventually, the grip gets tighter and goes on long enough to where these inferior companies go belly up due to the poor market conditions. Then, when conditions improve and supply slows or demand increases or both, Samsung now sells to the bankrupt companies’ former clients, as they need a new supplier.

The result: Samsung gains market share and comes out of the bottom of the cycle stronger.

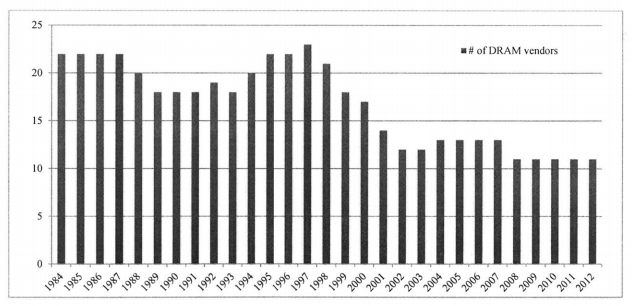

This process played out over the last several decades. And over the years, DRAM manufacturers halved – at least twice – with 23 existing in 1997 to 11 existing in 2012 to today, where only six exist by name – Samsung, SK Hynix (OTC:HXSCF), Micron, Nanya, Winbond, and Powerchip. But, the last three only make up 3.5% of the DRAM market. We’re then left with what is known as “The Big 3” – Samsung, SK Hynix, and Micron.

A Strategic Analysis of the DRAM Industry After the Year 2000 – Kyung Ho Lee, MIT

Today, these three companies claim more than 24% of the market each. Samsung remains the leader of the group with 41% of the market as of Q3 ’22, while SK Hynix owns 29.5% and Micron 24.2%. These three producers are the only DRAM companies worth mentioning. Together, in Q3, they made up 94.7% of the DRAM market.

What Is Samsung Thinking?

The financial media, analysts, and even commenters on my articles have either outright said Samsung is looking to go back to these old tactics to crush the market – which hasn’t been used in the last eight or nine years – or are worried this is at minimum posturing, with at least a temporary effect on the market through words.

My question is, what good does it do for Samsung to go down this path?

This strategy only works when you’re the market share and technology leader (at best, only the technology leader). And it’s well documented Samsung is not the technology leader and hasn’t been for a few years.

There’s little dispute to this end, especially as the lead continues into the 1-alpha and soon 1-beta node. But I’ll get to this shortly.

Therefore, Samsung flooding the market with lagging node technology only gives the technology leader the perverse advantage (everyone still loses), even if it has less market share. In fact, employing this tactic as the market share leader while its competitor is the technology leader would only draw itself further into the red.

And with Micron’s solid balance sheet, with a net cash position and more liquidity available through revolving credit lines, what is Samsung thinking?

It can’t crush SK Hynix and Micron like they’re 8% market share technology laggards from 2003.

The problem is viewing this move outside the context of Samsung’s current business position.

Look At It From Samsung’s Perspective

Logic concludes Samsung can’t gain the market share it hopes to by maintaining or increasing CapEx when its competitors can hang on. Don’t forget DRAM and NAND are Samsung’s cash cows, and going deep into the red with these businesses threatens its broader corporate business.

So if using tactics of decades past looks to be what it’s doing, but it’s playing the game from second place, why is it doing it?

The answer is found in a different question: what other purpose can this strategy serve? Or, more accurately and to the core of why this is even a topic for the market in the first place: why else would Samsung keep CapEx high?

There are several places to look to understand Samsung’s current market position. This understanding will provide a better logical conclusion than assuming it’s trying to play the market share game from a place of weakness.

Now, I don’t use the word weakness lightly. After all, I am talking about the biggest DRAM and NAND manufacturer on the planet. So allow me to point to exactly what I mean.

EUV Commitment Levels Led To Node Leadership Swaps

As I stated earlier, Samsung was once the technology leader. Micron currently holds the title. We need to know why this happened because it can lend clues as to why Samsung is going to spend more when it should be spending less.

There are a few reasons, some more speculative than others, but most are company-generated facts. For instance, Samsung was proud to have said it was the first to adopt EUV (extreme ultra-violet) lithography. This fabrication method is how the semi industry at large, whether logic chips or memory chips, will move forward to etch transistors under a certain size threshold (it varies among the different chip types and manufacturers).

Everyone needs to go this route at some point; no one denies this.

But Samsung was determined to intersect EUV as early as it could in its DRAM manufacturing process, as it expected fewer production steps and better yields.

On the other hand, Micron chose to continue the DUV (deep ultra-violet) route for a while longer, using its trusty multiple patterning process. Management felt there was a better cost structure for holding out on EUV and continuing its multiple patterning, plus it saw no reason to go to EUV if it was possible not to.

… we believe that the most efficient way to enable DRAM technology is without EUV… At least for Micron with the technology that we have for patterning, clearly EUV is not one of the things that should happen at least through [1-beta] of the roadmap.

– Scott DeBoer, EVP Technology Development, Micron’s Investor Day 2018

This was a year before Samsung began mass production of EUV-based DRAM.

Nothing changed for Micron between its stated strategy in 2018 and today, while Samsung continued its EUV path from 2019 to today.

These two companies charted their courses in very different ways.

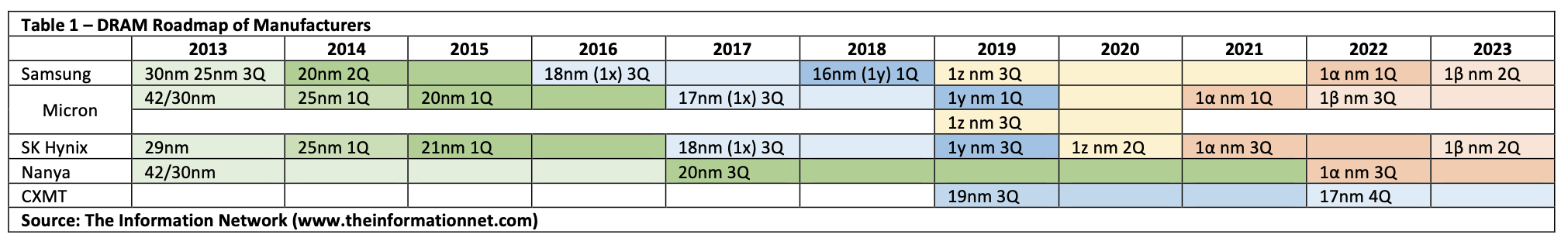

What we know now is this: Micron was behind one node by about 12 months in 2018 when these two companies embarked on two very different technology strategies, but nearly four and a half years later, Micron is ahead by one node by about 12 months.

theinformationnet.com

Don’t miss the alarming rate at which this happened. Micron moved two nodes faster during the last four years. Said another way, it means Samsung’s node progress slowed by 50% compared to the industry!

Yields Matter

But correlation is not causation, right?

Just because Samsung lost the technology lead spectacularly doesn’t mean its choice of lithography technology caused it.

But I have another topic that is causation: yields. And it’s not in the absence of lithography choice.

Yields are the crown jewel in semiconductor manufacturing. You may accomplish the most significant breakthrough in transistor size the world has ever seen, but if you can only yield 5% on every wafer, you’re going to go bankrupt or, at the very least, lose a lot of market share. This is because you need to not only fit more bits on a wafer but fit working, sellable dies on a wafer.

Yields from Samsung’s logic side (think CPUs) have widely been reported to be atrocious, trailing its counterpart and competitor, Taiwan Semiconductor (TSM), by 50%, yielding only 35% to TSMC’s 70%. This was apparent with Qualcomm’s (QCOM) mobile processors.

After Samsung met with Qualcomm in the U.S. last year, a Qualcomm executive allegedly said that even if it wanted to, Qualcomm couldn’t give more business to Samsung because of the yield problem. And as it turns out, the Exynos 2200 AP has had a lower yield than the Snapdragon 8 Gen 1 which would seem to indicate that the problem lies somewhere inside Samsung Foundry.

Worst yet, there are claims Samsung lied about its yields, and through these allegations, an investigation was started internally at Samsung.

The logic foundry obviously differs from the memory side and how DRAM yields are performing. However, things only get more complicated for manufacturing when going to memory. And when both the logic foundry and memory lines are using EUV equipment, there clearly aren’t any helpful tips and tricks being shared across the company. Otherwise, the memory division would be helping the logic division.

But thanks to some insider information from an engineer in the trenches, there’s credible information regarding Samsung’s ramp of 1Z – its first EUV node – subsequent nodes, and even an inability to get a 1-beta node to work altogether. The bulk of this legwork was done by Dylan Patel over at semianalysis.com:

[Samsung hasn’t] been able to ramp 1Z. They haven’t been able to ramp 1 Alpha, and now reports are coming out that they have canceled development of the next generation 1 Beta process node! Others report that Samsung is driving another topdown hail Mary by pushing straight to the 1 Gamma node. The cancellation report has a high degree of credibility as it is based on a disgruntled engineer at Samsung. He even posted a blog about this topic!

The engineer has been verified to be part of the technology development team for Samsung’s DRAM. He wrote a letter to the two heads of Samsung Electronics, Chairman Lee Jae-yong and CEO Kye Hyun Kyung describing the failure and issues. The blog was since taken down, but Korean media has captured some quite concerning quotes from it.

I’ve heard quite a few stories of ‘crisis’, but I think this moment is more dangerous than ever. In the midst of the successive occurrences, it seems that the top decision maker is not able to grasp the root cause of the problem.

Samsung DRAM Technology Development Engineer (Google Translate)

There are a lot of red flags for Samsung in just these two or three paragraphs. First, being unable to ramp means yield problems. Notice the first ramp to go poorly was where EUV was introduced. That’s not a coincidence.

Pushing the node on a mass scale continued to show yield issues and, therefore, could not continue to switch lines to the node. This leads to bottlenecks, output suffering, and the transition from the previous, more costly node never happens. This results in three things suffering: technology leadership, cost-per-bit advantages, and market share.

But there’s even worse news in the idea it’s abandoning an entire node! A leader in technology doesn’t pour billions of dollars into node R&D, double down on it, and then cancel the project.

As a result of the Financial News coverage on the 12th, it was confirmed that the Semiconductor Research Institute, which is in charge of advanced semiconductor development at Samsung Electronics, recently gave up research and development (R&D) for 1b, a DRAM in the early 10-nano range. In the second half of last year, they even established a dedicated 1b DRAM team to show their commitment to the project, but in the end, they failed to overcome the ‘nano wall’. In this regard, a company official said, “An email with information on the 1b abandonment (drop) was sent to executives and staff members who were conducting the research.” There are in-depth discussions about the direction,” he said.

(Google Translate)

An inability to ramp and the decision to drop an entire node to skip to an even more difficult one are not the tenets of a company firing on all cylinders. In fact, someone might want to check if the pistons are even moving.

But worse than that, skipping a node means spending more production line time on the current poor-yielding node while the only fully ramped node is two generations behind. Any cost-downs have nearly stopped entirely. Samsung is setting itself up to fall even further behind its competitors with this decision, both in time and market share.

Market Share Trends

The allegations of poor company workings can be just that, allegations. But when insider information is about as confirmed as possible, it leads to some solid conclusions. However, there is no better conclusion than the cold hard numbers. And the numbers that don’t lie are market share numbers.

Whether you agree or disagree with my assessment thus far, the following chart sets everyone straight.

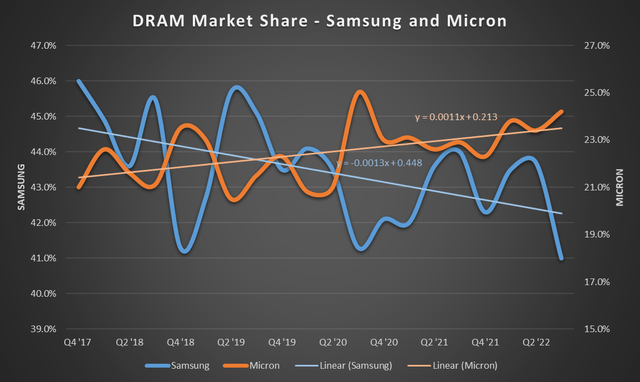

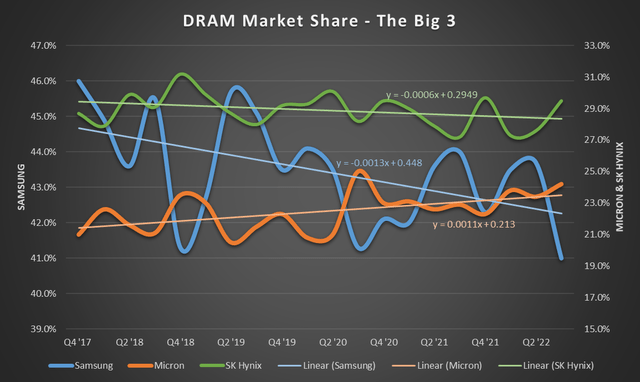

Chart mine (Data from Statista (derived from Trendforce) and Business Korea)

If I take just Samsung and Micron and plot them on their own axis (to normalize the picture), you can see two things. The first is the independent trend of Samsung’s market share from Q4 2017 to Q3 2022 is in decline. In contrast, Micron’s market share is on an upward trend. Of course, the trendline chart representations are not one-to-one across each company, but their slope equations are accurate and comparable to each other. Second, look closer at some of the more significant moves, and you can see market share being given and taken directly from one another.

If I put SK Hynix on the chart, you can see both Micron and SK Hynix tend to take market share together from Samsung. But what you notice is SK Hynix’s overall market trend is also slightly downward, albeit far less than Samsung’s. Micron is the only DRAM manufacturer taking consistent market share over the last four years. This isn’t a coincidence. This is due to better technology and cost structures. Micron can sell – on average – more bits than its competitors.

Chart mine (Data from Statista (derived from Trendforce) and Business Korea)

I noticed the recently reported quarter (Q3 ’22) is one of the most severe drops for Samsung in this period, while both SK Hynix and Micron picked up that market share. In fact, Samsung’s worst level of market share in eight years was the most recent quarter.

Samsung Electronics’ DRAM sales fell 33.7 percent from US$11.121 billion in the second quarter to US$7.371 billion in the third quarter. The drop eclipsed the overall market decline. As a result, its market share in terms of sales also fell by 2.7 percentage points from 43.7 percent in the second quarter to 41.0 percent in the third quarter. This marked the lowest share in eight years since the third quarter of 2014 based on IDC data.

Samsung hasn’t seen this low market share since the same quarter in 2014. If this doesn’t highlight how the mighty have fallen, I’m not sure what does.

But going back to the picture of all three manufacturers, notice the inflection in Micron’s market share was in the middle of 2020.

What happened there? That’s when Micron caught Samsung in node technology, according to Castellano. From there, Micron’s market share starts a solid upward trend.

You’ll also notice SK Hynix, the next closest in technology, loses less market share than Samsung (looking at the trendline again). However, because it still lags Micron, it can’t gain overall market share; it’s only taking it from Samsung.

The bottom line is Micron’s technology leadership is organically taking market share from its competitors, and Samsung’s technology backslide has given up market share.

So, Samsung’s Spend And Supply Strategy

With the above research and analysis now under our belts, we can arrive at the answer to the question, why is Samsung maintaining CapEx at near relatively high rates for DRAM with expectations for a menial 5% cut from 2022 levels?

Samsung’s outward problems started with its all-in-on-EUV strategy. Since then, the company has failed to get to the next node, yield it, and ramp it successfully, either logic or DRAM. The single decision to use EUV as early as possible caused Samsung to go from first to arguably last in everything but absolute market share; however, that is also shrinking quickly.

Samsung has no choice but to continue to spend on its costly EUV endeavor; there’s no way to move backward in lithography. Its highest volume node is still 1X, according to Afzal Ahmad, guest posting for Dylan Patel, and it wishes to spend this coming year’s CapEx to ramp 1-alpha – the same node it can’t yield good results on. It’s also the same node before the one it’s giving up on.

Spending CapEx to ramp a poor-yielding node will not grow supply to the level Micron’s 1-alpha node can on a like-for-like basis. Poor yields not only hurt the cost per bit – putting Samsung further into the red – but it doesn’t expand overall output as one would expect as it transitions away from prior well-ramped nodes.

Pushing 500 bad apples to market in a harvest of 1,000 apples is worse than pushing 50 bad apples in a harvest of 500. Sure, you’re putting out 50 better apples than your competitor, but it took you 100% more of a harvest to do it. That’s throwing good money after bad and not fixing the reason you’re harvesting 50% bad apples compared to your competitor’s 10%. It also correlates to the supply needed to dent the market.

To bring it back to company-shared info, have you noticed Samsung’s use of the word “artificial” when questioned about this?

““We are not considering an artificial production cut,” Han Jin-man, executive vice president of memory business at Samsung”

There’s a reason the word artificial is used. It’s creating its own production cuts by continuing to ramp what isn’t rampable.

It isn’t king of the hill, and its decisions here will only make it fall further behind.

My point here is even the term “pyrrhic victory” isn’t accurate. It can’t be victorious in this process. It makes Samsung a smaller producer in a negative feedback loop of investments. More investments will yield the same or worse results, resulting in fewer dollars to invest to do it again. Eventually, Samsung burns itself out. There’s no victory to be had – maybe a quarter or two of slightly regained market share, but for a smaller company.

Not Spooked By Continued CapEx Investments

Here’s the bottom line. If Samsung were to cut its CapEx, it would, in turn, be putting itself even further behind. So, suppose Samsung were to follow the industry CapEx spend trajectory into this downcycle. In that case, it will continue to move in the direction it has: backward and into the market share hands of its competitors.

So, it must spend as much as it did regardless of industry fundamentals even to maintain its current status. This is because the efficiency of CapEx is not the same as Micron’s or even SK Hynix’s. Every dollar Samsung spends is likely to wind up as a 70% efficient dollar, whereas Micron is closer to 90% and SK Hynix is near 80%. Don’t equate Samsung’s spending as one-to-one with its competitors. Spending $10B on more EUV equipment and lines yielding less than 50% will be the equivalent of a CapEx cut in and of itself.

However, watch what it does with its production lines versus its CapEx in the coming weeks. Reducing supply from a production line cut avenue is a telling sign of what I’m saying in this article: it must continue to spend to not fall further behind in technology, but it must also work with pricing so it can prevent huge losses in the process.

In the end, I don’t expect Samsung to make any significant cut to its CapEx, even after its earnings report at the end of the month. If it does, it’ll be trivial.

And lastly, don’t let the news spook you out of Micron. Samsung doesn’t have the teeth necessary to make significant gains in DRAM. Even in NAND, the company is behind in layer technology, though it may bump the small players enough to see more consolidation on that side of the memory industry.

If you get nothing else out of this article but this, it would be a win: keeping CapEx higher does not correlate directly to supply in Samsung’s case; it’s merely trying to right poor decisions. But in the end, it’s only pushing further into those poor decisions. The truth is, Samsung has nothing to do except spend its way forward just to stop the technology slide. Therefore, Micron won’t be hurt any more than if Samsung cut spending, and the downcycle won’t be materially shifted.

Editor’s Note: This article discusses one or more securities that do not trade on a major U.S. exchange. Please be aware of the risks associated with these stocks.

Disclosure: I/we have a beneficial long position in the shares of MU, QCOM, TSM either through stock ownership, options, or other derivatives. I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it (other than from Seeking Alpha). I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.

Decrypt The Cash In Tech With Tech Cache

Do two things to further your tech portfolio. First, click the ‘Follow’ button below next to my name. Second, become one of my subscribers risk-free with a free trial, where you’ll be able to hear my thoughts as events unfold instead of reading my public articles weeks later only containing a subset of information. In fact, I provide four times more content (earnings, best ideas, etc.) each month than what you read for free here. Plus, you’ll get ongoing discussions among intelligent investors and traders in my chat room.