Summary:

- Convergence is the priority of the moment for all telecom service providers.

- Fiber and fixed wireless broadband are key growth areas, but AT&T is slowing down its fiber build rate.

- AT&T could dramatically boost its growth rate and improve its competitive position by increasing its fiber build speed.

- While a dividend cut is unlikely to happen now, missing the boat could make it more likely in the future.

AT&T might be not agile enough to win the race Ryan McVay/DigitalVision via Getty Images

Convergence is reshaping the telecom space

Currently, there is a clear trend in the U.S. telecom industry: You can either gain customers by offering a simple, efficient and relatively unexpensive “good-enough” solution for all the customer’s digital needs – or you can gain customers thanks to a high-quality, reliable broadband service, ideally coupled with a wireless connection.

The first is where T-Mobile (TMUS) is clearly leading with its fixed-wireless broadband offering, but the end of its boom is probably in sight. Effectively, during its Q4/22 earnings call, the company at least partially acknowledged this issue, by saying that fiber is clearly the faster solution with greater capacity. T-Mobile is actually already thinking about augmenting its offerings with some sort of fiber backbone or network expansion.

Initially, the company aimed for 7-8 million homes to connect to its FWB service and now considers 40 to 50 million homes to be eligible. That’s about one third of all U.S. homes. However, a typical uptake might be in the 30-40% range, which means that even in a best-case scenario, T-Mobile can connect a total of 12-20 million homes. So that’s probably the limit. (But there is still way to go from the current level of 2.6 million FWB homes serviced.)

The latter is where all other providers compete, and cable broadband providers like Charter (CHTR) and Comcast (CMCSA) have an advantage since they can already offer a simple converged bundle to their customers. While at home, they enjoy cheap, unlimited high-speed data connections, while outside, they get Verizon’s (VZ) 5G network thanks to MVNO agreements. The only limitation is the extension of the cable footprint.

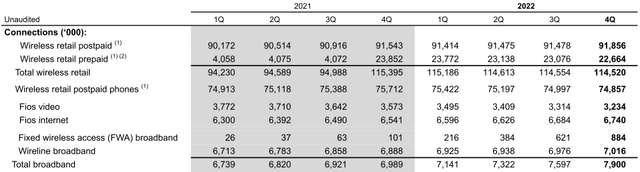

Interestingly, both cable broadband providers’ only meaningful growth in 2022 was in their wireless subscriber numbers, while Verizon actually reported noteworthy subscriber growth only in its broadband services, whereas total wireless retail connections were down YoY (when considering 3G subscriber losses):

Hence, the industry is already converging and all competitors want a piece of the broadband/wireless connectivity pie.

The land rush

As AT&T (NYSE:T) CEO John Stankey pointed out during the recent Q4/22 earnings call, there is sort of a “land rush” going on in the telecom space – and its ultimate goal is to provide a converged service offering:

I think it’s a bit of a — I don’t want to use the term land rush, because it’s not it’s not that easy to put fiber and it takes a little bit longer than a land rush, but we are definitely in a window right now where I do believe a good portion of the United States will ultimately have a fiber connection to it. And I believe there will be — if you think about this over the long haul that we’re moving to an industry, and I’ve been pretty clear about this, ultimately, customers are going to want to buy connectivity from one place. They don’t necessarily love making a distinction between their fixed provider and their mobile provider. And I think over time, we’re going to see an ordering of industry assets that leans more toward that. And my point of view to be in a strong position as you — if you have the best technology out there and you ultimately build the largest footprint fastest, you’re going to be in a better position to ultimately play in the outcome of how that restructuring gets done, and you’re going to have the strongest customer base on a relative basis and owning and operating those assets and having the ability to control the product offering and control the cost on it will be the best way to control your progress going forward.

The wording is interesting: “land rush” means that there are only a few high-return areas to build out and whoever comes first will take the bulk of the potential gains. This is because, historically, in any given area up to two service providers could earn their cost of capital, but once a third network entered the competition, returns became unattractive for all three.

During the AT&T call, industry analyst Craig Moffett mentioned that currently about 16-17% of the U.S. is already overbuilt with fiber. If all competitors meet their respective guidances, we should see another 10-12% of overbuild within a few years. AT&T itself is aiming for about 30 million homes, plus about 1.5 million homes within the “Gigapower” partnership and the BEAD-sponsored rural initiatives. Overall, since 30 million homes represent ~20% of all U.S. homes, this means that AT&T will likely have the largest fiber footprint of all competitors.

Yet time is of the essence. There is only a limited amount of land to grab and it will handsomely pay off to be the fastest land grabber.

But AT&T is actually slowing down its fiber build rate.

AT&T might still end up as a loser

During the earnings call, AT&T guided to a fiber build rate of 2-2.5 million homes per year. This is down from the very recent guidance of 3.5-4 million:

AT&T intends to become America’s best broadband provider, underpinned by a best-in-class network with fiber at its foundation. And by owning and operating both fiber and wireless, AT&T’s owner’s economics will provide better flexibility to deliver high-quality broadband in more places for businesses and consumers.

As part of this strategy, AT&T plans to double its fiber footprint to 30-plus million locations, including increasing its business customer locations by 2x to 5 million. In doing so, the company expects to add 3.5 million to 4 million customer locations each year.

Among all enthusiastic reactions to the Q4/22 report (which was probably more relief than euphoria, as many had feared a worrisome FCF guidance), I haven’t read much about this strange contradiction.

On the one hand, AT&T is aware of the need to speed up its fiber build (which is an essential part of its strategy), on the other hand it is slowing down.

The potential consequences are easy to see: If T-Mobile grabs most of the customers that are willing to switch to a cheap, easy connectivity solution that is good enough for most, while cable takes most of those that need more reliable connections at home or at work, if Verizon and AT&T won’t expand their fiber footprints fast enough, they will be left with rather expensive wireless subscriber adds that require more and more subsidies to make them switch.

Alongside the cable providers, AT&T was the only company to report net wireless subscriber additions in 2022. But this happened only thanks to massive subsidies, since it was in both the interests of consumers and telecoms to distribute as many 5G-capable phones as fast as possible. However, the phone upgrade cycle is lengthening. Industry-wide Q4 net adds were down 21% YoY. Inflation is pressuring consumers, and with many of them already owning a 5G-capable phone there is no urgent reason to buy another one. So one of the key incentives to switch providers or upgrade to a more expensive plan will be of reduced importance in 2023 and likely in 2024 as well.

While there are certain areas where fiber can be built with good returns, they are rare and all providers are trying to occupy them before their competitors. If AT&T moves slower, others will take its place, and there won’t be a second chance. Once two offerings are available in a determinate area, building a third one destroys economics for everybody.

What AT&T could (but probably won’t) do

Unfortunately, after reporting flat adj. EBITDA, a lower EBITDA margin and a substantially higher debt ratio of 56% in 2022 and guiding to lower EPS in 2023 due to higher interest rates effects on pension costs, AT&T needs to pay attention to its debt levels.

Of the $16B of FCF it guided to, over $10B are earmarked for dividends, and debt needs to come down as well, given rapidly rising interest rates. So at a time when capital is needed for future-proofing the business, the company is fundamentally constrained.

This is why it is already resorting to financial engineering with its “Gigapower” initiative. Once established, the joint venture with BlackRock (BLK) will be a highly leveraged off-balance sheet vehicle to enlarge AT&T’s fiber footprint without incrementing the company’s debt levels – at least on paper. AT&T will keep control of this JV, which will enable converged service offerings (which is key to the company’s strategy), but profitability will be dismal due to profit sharing and interest costs. Basically the only thing that will come out of this JV is access to a AT&T-controlled fiber network.

My personal – and likely highly unpopular – opinion is that the rational solution to this problem would be a dividend cut. Fortunately for the DGI crowd (well, in the case of AT&T eliminate the “G” from that acronym), it almost certainly won’t happen. But it seriously undermines the investment case for AT&T, as its consequence is a severe capital constraint, at a time when capital would be deeply needed.

More capital could rapidly buy some of the independent fiber networks out there or increment build rates, i.e. grab more land more rapidly. If AT&T loses this opportunity, T-Mobile likely won’t. At a time when both Verizon and AT&T are heavily hampered by their debt and dividend promises, the “un-carrier” will literally drown in cash in my view. By 2024 its FCF will probably match or even exceed AT&T’s. Since it doesn’t pay a dividend, it enjoys total financial flexibility. If it needs to move into fiber, it can do it rapidly. Otherwise it will simply buy back shares.

This is why T-Mobile trades for 11x FCF(2024e) and AT&T for just 8x FCF(2024e). This valuation discrepancy is not due to market inefficiency, since it merely reflects the direct effects on future competitiveness of lower debt levels, smarter capital allocation and capital efficiency. While AT&T is projected to spend close to 16% of its revenues on capex, T-Mobile just needs 12%. But most importantly, when it needs money for strategic projects, T-Mobile will have it – AT&T won’t. As a consequence, AT&T will likely lose share and competitiveness.

Cutting the dividend would certainly be a painful event, but it would put the company on a much better footing for its future – and shareholder returns would follow. Vice versa, diminished competitiveness could pave the way for a far more painful dividend cut further out.

Disclosure: I/we have no stock, option or similar derivative position in any of the companies mentioned, and no plans to initiate any such positions within the next 72 hours. I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it (other than from Seeking Alpha). I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.

Additional disclosure: I am long DTEGF which owns 49% of TMUS and long LBRDK which owns 26% of CHTR.