Summary:

- Berkshire Hathaway’s huge position in Apple Inc. reflects many Buffett principles: brand power, low capital needs, and finding growth in already large companies with good track records.

- One principle is starting small while testing a premise, ramping up rapidly as premise is strengthened, and having prices in mind to stop buying or sell a bit.

- Making Apple one of Berkshire’s “big four” treats it as a subsidiary, meaning an intent to ignore price and focus on operating results including “look through” earnings.

- Ignoring quarterly results, Buffett likely sees Apple as a combination of great management, solid growth, and optimal shareholder-friendly use of cash flow with large buybacks and small dividend.

- Buffett’s earlier model for Apple might be Coca-Cola: strong brand and management and a position now 94.5% cap gains with dividend yield of 55% on cost.

Chip Somodevilla

Apple Inc. (NASDAQ:AAPL) has played an important role in the evolving structure of Berkshire Hathaway Inc. (BRK.A, BRK.B). It was the company that pulled Berkshire into the age of technology. Benefiting from the advantage that comes with a strong brand, it was able to grow without adding a significant amount of capital. That’s the story of Warren Buffett and Apple in a nutshell.

Identifying companies like this was one of Buffett’s major skills from the early 1970s when he began to switch to great companies at a fair price. What made it work so well is the combination of brand power and technology. It also embodies the Buffett principle that you don’t need to find growth in new companies but can do very well with companies which have been around for long enough to have a track record. There’s an excellent book on this subject by Wharton economist Jeremy Siegel entitled The Future For Investors: Why The Tried And True Triumph Over the Bold And The New (2007).

Track record is important. It’s not the end of the story, but it’s a privileged starting place from which to establish your expectation for a company. Start-ups come with a cluster of more difficult questions. When will cash flow become positive? When will earnings appear and begin to grow? When will revenues begin increasing in comparison to costs? Which costs are essential only during the start-up period? Finally, and perhaps most important, how will this company treat its shareholders as soon as cash flow begins to gush?

The Berkshire portfolio contains very few companies which have not yet answered these questions. The few which are true startups illustrate the difficulties of trying to get in on the ground floor. Two startup financials, one in India and one in Brazil, were supposedly innovators which would overtake and disrupt the banking industry. So far this hasn’t happened and the companies have been disappointments. The model for a reasonable shot at this approach is Snowflake (SNOW), a cutting edge software company, but so far it has failed to answer any of the questions in the preceding paragraph.

Each of these innovators came from Buffett’s younger lieutenants and thus started as a small position which has so far not been scaled up. Why? They just have not been successful enough to warrant a larger position. It’s a basic investment principle: keep your mistakes small. An accompanying question: some investment decisions are just too hard. Principle number three: Starting small is frequently a good idea and has both math and subjective judgment behind it.

Buffett Started With A Nibble Then Took Larger Bites

A small position is enough to let you know if your premise about a stock is not working well. You then have two choices. You can dump it or you can keep it and tell yourself that you were smart enough (or lucky enough) to start with a position that is not very consequential. Who knows, it may just need a little more time. I have done this a few times and have a moderate degree of patience. I don’t recall a recent occasions when I regretted dumping an underperforming small position.

Berkshire started buying Apple in 2016. As he later acknowledged, it was not Buffett who bought the first position but “the boys,” Todd Combs and Ted Weschler, with the single buyer not named. it’s tempting to think that purchases like this are part of the job for Todd and Ted. Buying a small position brings it to the attention of WEB who can ramp it up or not. It’s not his buy, at least in the beginning. You think differently about a stock once you own some of it – even a little bit. During the early days of the Great Recession Crash, I bought Citi (C), which looked cheap on the stats. I sold it at a $1000 loss 24 hours later when I had fully absorbed what it felt like to own it. I never regretted that sale, as those of you who were in the markets then will fully understand.

Buffett thought about Apple in a way I suspect “the boys” did not. It was more than a growth stock. It was more than a tech stock. It had good management which did reasonable things with capital. It was friendly to its investors. It understood the power of buybacks. CEO Tim Cook had emerged from the shadow of Steve Jobs. You could argue that Cook replaced Jobs at exactly the moment his qualities were needed, a manager who could preside over the continuing growth and health of a highly innovative company. Buffett had exactly the right knowledge and experience to recognize the strengths of such a company.

Apple’s brand was unsurpassed, but it was still just half the story. This popped into my mind whenever I saw it included among the FANG stocks. Apple wasn’t really one of them. Compared to Apple, Facebook (META), Amazon (AMZN), Netflix (NFLX), and Alphabet (GOOG, GOOGL) looked like one-trick ponies. Amazon came closest to Apple with its ability to get into new businesses, but it was far behind Apple in acknowledging that it had obligations to its shareholders. Netflix seemed to have no idea how to position its product. Facebook and Alphabet had no idea what to do with their gobs of cash. Both involved themselves in projects which burned cash without much contribution to the future of the company. Critics refer to these sidebar investments as “science projects.” Apple, on the other hand, knew how to run a complicated business and keep it growing. It worked its way to being the most valuable company in the S&P 500.

There’s a piece of very nifty math behind Buffett’s reasoning. There’s a time honored market adage that says you should add to you winners and trim or dump your losers. In my personal experience it works as long as price behavior isn’t random noise. The slightly mathy reason is known as Bayes’ Theorem. I’ll spare you an explanation of the simple equation because it’s easy to google. It basically says that you start with a premise about some kind of event, place a probability on it, then modify that probability as new information becomes available. It works very well for things ranging from whether to bid then drill on oil tracts to how an election is likely to turn out (read Nate Silver).

The anecdotal version is that if you receive positive information about your premise you increase the probability and ramp up your bet. If you receive negative information you decrease the probability and reduce your bet or get out of it altogether. It has a nice subjectivity because you are estimating the probability from the get-go and doing the same on updated data. It’s great for problems which require estimating on limited data and hoping to be broadly right. That’s why it’s a good idea to have a Margin of Safety. Some are better estimators than others, of course, especially when it comes to the long term. Buffett clearly thinks in these terms although I would bet real money that he has never bothered with the formalities of Bayes’ Theorem. What he would like is the principle of being broadly right rather than exactly wrong about the main thing. It’s coincidentally thinking along the lines of Bayes that has made him the best long term investor ever.

It’s pretty clear that Buffett started ramping up his Apple position with a premise. That premise was made up of several factors. Apple had competitors but it knew how to deal with them and prevent them from developing into existential threats. He also had as part of his premise that Apple would continue to grow in the future albeit at a slower rate. In this respect Apple resembled Berkshire Hathaway in that it throws off more cash than it can use in internal reinvestment. Its size also presented a similar problem in that it needed great leaps to move the needle. The size, in fact, was large enough that its revenues might be expected to begin slowly converging on the rate of population and GDP growth.

For Buffett, the diversification of Berkshire with its 100 businesses and large stock portfolio gave it an advantage of making acquisitions, adding bolt-ons, or adding stocks in different fields. This was not part of Tim Cook’s skill set, but at least he was honest about it. Instead of wasting money on “science projects” like some social media companies he paid a small dividend while buying back shares on a large scale, until last year around 5%. Sometimes the share repurchases were done at prices that appeared to exceed fair value for Apple stock. Buffett wouldn’t do this with Berkshire but didn’t seem to be worried about Tim Cook doing it at Apple.

I wrote this March 5, 2022, article puzzling about the apparent inconsistency, Having just reread it in its entirety (it’s rather long), I consider it one of the most important articles I have published in Seeking Alpha. In 2022 through September (and also TTM numbers) Apple continues to execute about the same level of buybacks in dollar terms, although the percentage of shares bought back declined to about 3% because of the higher average price paid.

Buffett’s premise with Apple was that there was a price at which Apple was dirt cheap (his earliest purchases), a price at which it was still cheap enough to add, a price where it wasn’t rational to add (starting in the middle of 2018), and a price at which it made sense to sell – a little. Buffett’s actions suggest that he considered Apple dirt cheap at a split-adjusted price around fifty and overpriced enough to sell a bit somewhere between 100 and its current price around 150. These numbers reflect an allowance for margin of safety. Also note that these are moving targets for overall value. There was also a nifty piece of arithmetic detailed in the above-linked article because Buffett could define the shares sold as being the ones purchased at the highest price (for tax efficiency). As a consequence, he would have been able to reduce his cost basis by 25% by selling just 10% of shares owned. That’s what happens when you sell tranches at a much higher price than your average cost.

Is there a point where Buffett would actually dump his entire position? i think not. Buffett’s original premise would likely include a broad area of price at which he would do no more buying, but at which he would also do no more selling. What we should pay attention to is the way Buffett’s thinking about Apple probably shifts as it evolves and trades moderately over and under a moderately rising upward trend.

What Apple Means As A Holding Within Berkshire

The first thing to note about Berkshire’s large position in Apple is that is not just a publicly traded stock position. Buffett’s language when talking about Apple is different than the language he uses for other positions in publicly traded stocks. He describes it as one of the “power four” or the four “Family Jewels.” Note that the other three are wholly owned subsidiaries: insurance companies, BNSF Railroad, and Berkshire Hathaway Energy. Buffett seldom throws around terms like the above casually. What he is saying is that he thinks of Apple as if it were a wholly owned subsidiary.

There are several reasons Buffett might look at Apple that way. The first one is that Apple is very large not only as a percentage of Berkshire’s stock portfolio but also a percentage of its book value. At its current price of about $152 per shared the value of Apple shares held within Berkshire is about $135 billion based on numbers from December 31, 2021 (thus not including tweaks in Berkshire’s position in 2022). That $135 billion is about 20% of Berkshire’s total book value. Due to Accounting Standards Update 2016-1 Berkshire must report unrealized gains and losses in Apple’s price in its quarterly income statements. That number also drops into Berkshire’s balance sheet. A 33% drop in Apple’s stock price – entirely possible if the bear market in growth stocks resumes – would thus crop about $36 billion from Berkshire’s book value after discounting tax liability. If taken at face value this have would significant impact on things like Buffett’s hurdle for buybacks, in which book value is a factor.

It’s well known that Buffett disagrees with ASU 16-1 but when it comes to Apple he probably has in his own head an estimate of the fair value of Berkshire’s Apple position. Owning 5.7% of Apple on the most recent public numbers he probably treats it as a wholly owned subsidiary on about that scale. That number might be inferred from the prices at which he stopped buying and sold a bit. Buffett’s personal estimate Apple’s business value is likely grounded in “look through” earnings, an approach he has described from time to time. Here’s what he said in his 1997 Annual Letter:

In past reports, we’ve discussed look-through earnings, which we believe more accurately portray the earnings of Berkshire than does our GAAP result. As we calculate them, look-through earnings consist of: (1) the operating earnings reported in the previous section, plus; (2) the retained operating earnings of major investees that, under GAAP accounting, are not reflected in our profits, less; (3) an allowance for the tax that would be paid by Berkshire if these retained earnings of investees had instead been distributed to us. The “operating earnings” of which we speak here exclude capital gains, special accounting items and major restructuring charges.

While written for major Berkshire holdings, it might apply equally well for an any investor owning common stock with the actual intent of regarding it as a business rather than a speculative vehicle and holding it for the long term (ideally forever). All serious investors should look inside a company’s operations and understand that ownership includes proportional ownership of everything. Mere visible returns such as dividends are incomplete and are in some respects the least valuable returns because they remove cash from the process of compounding.

Every investor should do “look through” analysis with every major holding, and the financial data here at SA is helpful. What’s a little harder to grasp, however, is Buffett’s view that you actually “own” the retained earnings on the balance sheet and the earnings growth they generate. It’s the hybrid case of “equity method” treatment of partial ownership exceeding 20% that puts this in focus. For years Berkshire has included its Kraft Heinz (KHC) holding in this category.

More recently investors focused on whether Berkshire might ultimately buy Occidental Petroleum (OXY) outright as its percentage of ownership approached and then passed the 20% threshold. In actuality outright ownership would have come with a few problems, including the willingness of OXY shareholders and management to be absorbed and become a Berkshire subsidiary. Getting above 20% ownership provided the very material advantage of including that proportion of OXY’s numbers within its own results. Rather than imagining the “look through” impact a Berkshire investor could actually see it In Berkshire’s financial reports.

It’s highly unlikely that Berkshire’s stake in Apple will ever exceed 20%. Even if the several hundred billion cash could be made available it would require almost quadrupling its present position while paying an astronomically higher price than its present average cost. That being said, everything Buffett has said about Apple makes it unlikely that he will sell Berkshire’s position any time soon. There are very good reasons to believe this is the case. For one thing, at its present price close to 80% of the market value consists of long term capital gains. While dividend yield is low at roughly .6%, shareholder return including share repurchases is likely to fall into the 4-5% range. Assuming that Apple continues to be broadly stable and profitable it would make little sense to sell and turn over billions of dollars in capital to the IRS.

Will Apple continue to grow? There’s no reason to think it won’t. Its long term growth has unfolded in cycles driven by product upgrades. This was known when Buffett formulated his original premise. Growth will undoubtedly slow because of Apple’s size but to this point Apple has aged gracefully. Those who made Apple a battleground stock back in 2016 on a basis of quarterly results were losers. Those with a strong long term premise were the winners.

Is Coca-Cola The Model For Apple’s Future As A Berkshire Holding?

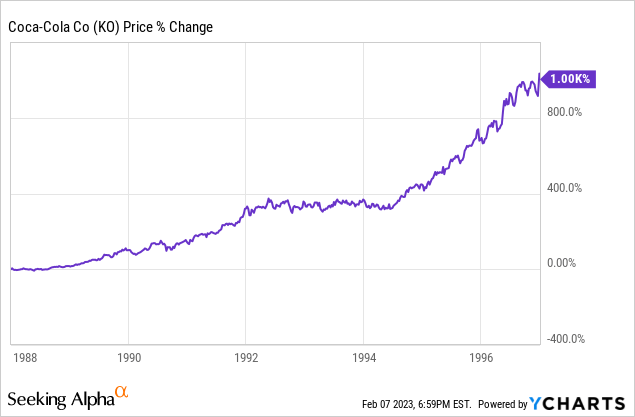

Buffett initiated a billion dollar position in Coca-Cola (KO) in 1988 and 1989, when it was dirt cheap in the aftermath of the 1987 Crash. He then added about #275 million in 1994. His buying in stages with attention to price resembles his buying in Apple. From 1994 to the present he did not sell and did not add. In 1988 Coca-Cola had been around as a company for over a hundred years, having taken its present name on January 1,889. Surely its heroic growth years were behind it.

As it turned out, 1988 was an excellent time to buy Coke. CEO Roberto Goizueta ruled with a steady hand expanding in foreign markets, adding flanker products, acquiring businesses with a product that fit, and even branching out by buying things like Columbia Pictures which didn’t turn out to be a home run but was sold at three times its purchase price. Meanwhile Coke defended its brand, helped by Buffett himself who made sure he was seen publicly chugging Cherry Cokes. The chart below shows that within ten years Coca-Cola was a ten bagger for Berkshire Hathaway.

A few years later Buffett quietly admitted that he should probably have sold at the top. He knew very well that KO was overpriced. Its rise had been driven by a combination of growth and valuation. It was part of the Bubble-before-the-Bubble when ordinary growth stocks outperformed wildly a year or two before the dot.coms went even more crazy. Buffett couldn’t miss this because Berkshire Hathaway was part of the blue chip rally, having risen above 200% of book value. Buffett didn’t quite tell owners to sell it, but he strongly discouraged would-be buyers. Value mattered. Selling big winners meant paying taxes.

When it came to Coca-Cola Buffett spoke as if it were a close thing in which he hung on to Coke against his better judgment. In the end it turned out not to be such a bad decision. By 1998 the heroic growth days for KO were clearly in the rear view mirror, and it struggled to find new niches and markets. The stock price rose only about 50% over the ensuing two decades but it was a pillar of stability. Share buybacks became an important vehicle creating per share earnings growth. A slowly rising dividend added to the annualized rate of return. Over the past decade Coca-Cola became a popular TINA stock bought as a bond equivalent. At some point Buffett probably decided he was okay with that. Holding on to Coke hadn’t been such a bad thing.

Berkshire’s regularly reported cost and present value numbers for its portfolio tell an interesting story. The cost basis for Coca-Cola at the end of 2021 was $1299 billion, unchanged from 1994. Meanwhile, thanks to buybacks, Berkshire’s percentage of ownership had risen to more than 9%. For every dollar of profit Coke makes Berkshire owns 9 cents. At the end of 2021 the market value of Berkshire’s position stood at $23, 604 billion, making it Berkshire’s fourth largest position. The dividend yield is close to 3%. Its’ yield on cost is thus about 55%. Would Buffett buy more KO at its present price? Unlikely. Would Buffett sell any KO shares at the present price? Equally unlikely.

Coca-Cola’s history presents an informative picture of the life cycle of a company with a powerful brand. Over a century and a quarter it evolved from a single product to a company with many flanker products, survived a number of crises, and enjoyed a number of bursts of new growth. Now in its final phase it still managed to jump revenues a bit during the pandemic years and continues raising its dividend a modest amount every year. The power of its brand hold steady.

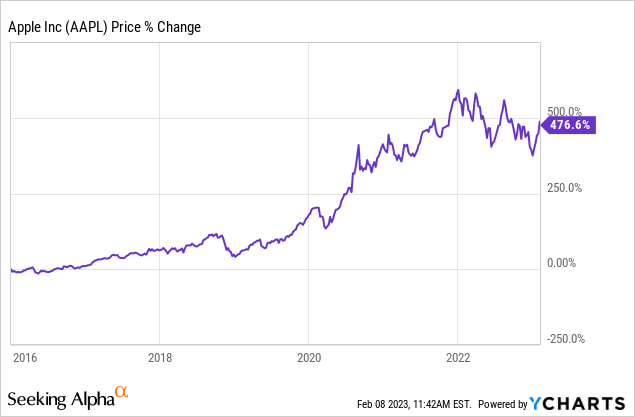

Like Coke, Apple began with a single product which used branding to establish and dominate a market. It has been fortunate to replace a near perfect founder with a near perfect manager. Everything has gone it way. It requires very little capital. It now pays out most of its cash flow to shareholders with a carefully calculated combination of dividends and buybacks. Its buybacks reduce the number of shares almost exactly the amount needed to enable regular per share increases in dividends without having more aggregate cash go out the door. There’s a managerial genius in accomplishing that. Here’s the Apple chart encompassing the period in which Berkshire has owned it:

The question about Apple is whether it resembles the Coca-Cola of 1988 or the Coca-Cola around the year 2000 or later. Is its final burst of major growth in the past or the future? That’s hard to estimate, and the answer is probably somewhere in the middle. It’s hard to get a good take on the future of Apple in huge countries like China or rapidly growing countries like Nigeria. Is there a future in which most individuals in those countries use Apple products? As difficult as it is to game this large question it is really the only question. Apple has enjoyed somewhat lumpy growth in the past. Quarterly earnings ups and downs are only helpful to the extent that they provide hints in answering the big question about its future.

Conclusion

Buffett often talks about Berkshire Hathaway in terms of the limitations imposed upon it as it has grown to be one of the world’s largest corporations. For two decades he has frequently said that Berkshire is likely to see its long term outperformance in comparison to the S&P 500 shrink. He acknowledges that it has reached a size where 20% outperformance compared to the S&P is extremely difficult. Because the S&P 500 adjusts cap weightings daily the importance of its fastest growing companies grows automatically. For Berkshire it would be necessary for Buffett to find extraordinary growth stocks on a regular basis and build huge positions. Moving the needle on Berkshire’s scale is exceptionally difficult. The best thing Buffett and his future successors can do is keep up with the S&P 500 with less risk and volatility and perhaps beat it by a percent or two. As I wrote here, that may well be part of the reason his will specifies that his wife’s inheritance be invested passively in the S&P 500.

Apple solved a number of problems for Buffett and Berkshire Hathaway. Large and growing investments like Apple are obviously essential to Berkshire’s growth. It’s hard to argue now that Berkshire has no stake in technology or that Buffett doesn’t understand it. In fact, critics of Berkshire who focus on Buffett’s tech investments have basically gone dark because of Apple. Buffett not only went big with technology, he arguably leveraged his knowledge of brands to buy the best company. Apple has sidestepped many of the problems that the more purely techy FANG stocks have encountered. For one thing, Apple does not have the problem dealing with spare cash which has led the others into bad investments. Berkshire is now a highly diversified conglomerate which owns its share of tech.

The most important contribution of Apple may lie in the way Buffett looks at its value as an operating company. By making it one of the four most important Berkshire units, second in rank by size, he is comparing it to wholly owned subsidiaries which no longer trade in the public market. As such he can be indifferent to its market price. Because he doesn’t own the 20% required to consolidate Berkshire’s ownership of Apple via the “equity method,” he relies upon his own estimate of what the result would be if he could, relying upon the “look through” method of valuation described above. That’s the most important takeaway for other investors. The method is simple and can be applied to all your holdings.

Disclosure: I/we have a beneficial long position in the shares of BRK.B, GOOG either through stock ownership, options, or other derivatives. I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it (other than from Seeking Alpha). I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.