Summary:

- Three critical battery metals, lithium, nickel, and cobalt, are all positioned to enter a significant shortage by 2024 that is expected to last throughout the rest of the decade.

- This issue is made worse by the fact that there are few alternatives to these metals and, in the case of lithium, there are none.

- While other automakers have been able to secure supply by communicating directly with miners, Lucid and Rivian lack the size, money, and power to do so.

- This shortage will impact both companies’ competitive strength, vehicle output, and ability to maintain profitability.

- This risk seems to be largely overlooked and stands to severely limit the growth of both companies, therefore implying a significant overvaluation at current prices.

SolStock

Supply chains have gained a lot of attention over the past few years, especially in the automotive sector. But as most automakers are now on the tail end of having to deal with parts shortages, I believe electric vehicle (“EV”) makers are just on the cusp of a far more significant, and enduring, shortage for battery metals. While this will hit all automakers with EV targets, young EV manufacturers will likely be hit the hardest as they struggle to find a seat at the table. This article will seek to examine this potential raw materials shortage and what it might mean for Lucid Motors (NASDAQ:LCID) and Rivian (NASDAQ:RIVN).

Lithium

The problem in the lithium market is pretty simple. Before EVs, lithium was really just a specialty chemical added to some glassware to broaden its range of operating temperatures. This may shock you, but that wasn’t exactly a massive market.

In 2010, the year the Nissan Leaf and Chevy Volt made their debuts, there were 28,100 tonnes of lithium, or 149,600 tonnes of lithium carbonate equivalent (“LCE”), mined. In 2022, 636,000 tonnes of LCE were produced. That’s a 4.25x jump in 12 years. Lithium production was still only around 202,300 tonnes LCE per year in 2016, meaning this massive growth has really only happened in the past six or so years.

This sort of extreme growth, especially for such a small industry, is incredibly hard to accomplish. Even now, the pool of experienced personnel is extremely limited. While there are some synergies between oil extraction and brine extraction, this doesn’t address the complex matter of producing battery-grade lithium compounds.

Contrary to popular belief, producing battery-grade lithium compounds is not a plug-and-play system. Every deposit has unique mineralization, which requires unique treatments to remove various impurities. Battery-grade lithium carbonate is anything that is at least 99.5% pure, which isn’t exactly a simple standard to meet.

For this reason, I don’t think it’s fair to consider the lithium market to be a commodities market. Instead, I view it as a specialty chemicals market. So we have a specialties chemical market experiencing extreme growth, with only a handful of specialists truly qualified to lead it.

The limited size of the industry also makes financing new projects incredibly difficult. Following a price boom in 2017, where lithium carbonate prices reached a peak of $25,000 per tonne, the market fell into rut. Albemarle (ALB) halted production at one of its Australian mines in 2019 and prices bottomed at around $5,750 per tonne in 2020.

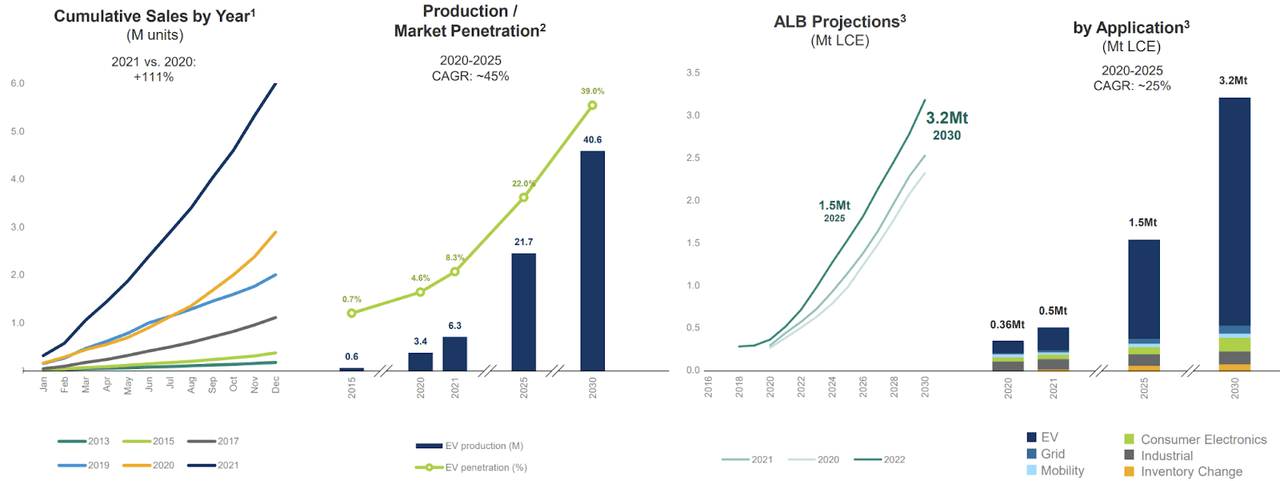

For about three to four years, no one wanted to finance new projects. The risk was too high. Because EVs are now the primary driver of demand, any weakness in EV demand will significantly impact lithium demand. But with the market logging multiple years of more than 100% growth, building an accurate forecast is nigh on impossible.

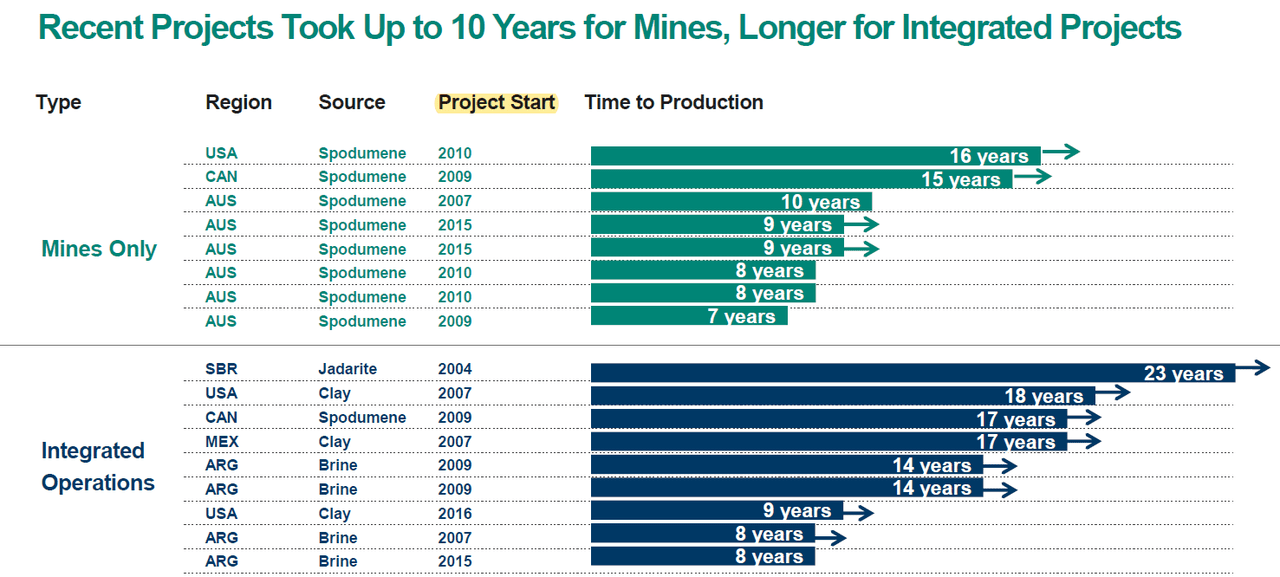

The final major issue that the market faces is the time to production for new mines and expansions of old ones. The figure below highlights the development timeline of a number of lithium projects around the world, exasperating the impact of the financing issue that I previously discussed.

Albemarle

Forecasting demand even one year in advance is an incredibly difficult exercise. To do so 7+ years in the future is borderline guesswork. Without the confidence of financiers to make early investments in establishing a strong lithium supply, the continued strength of the market has left suppliers trying to play catch up. However, given the long lead times to production, it seems highly improbable that suppliers will be able to catch up for at least another seven years.

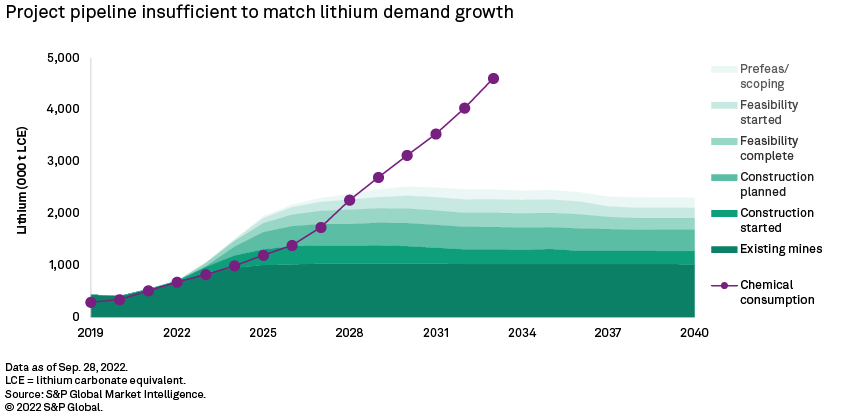

This is corroborated by data compiled by S&P Global Market Intelligence. The research agency estimates that there are currently 53 lithium projects in development that are past the preliminary economic study stage. While that may seem like a lot, S&P notes that even if all 53 projects make it into production by 2030, the market will be in a 605,000-tonne deficit. However, in reality, the agency expects just 42 projects to make it to production by 2030.

S&P Global Market Intelligence

The figure below highlights a demand projection from Albemarle, building the case for the company’s estimate of an 800,000-tonne deficit in 2030. That’s a 25% shortage, based on its demand estimate of 3.2 million tonnes LCE, and 24.8% larger than the entire lithium market in 2022.

Albemarle

Given the aforementioned long lead times to production, we can predict future supply, at least for around seven years, with pretty high accuracy. Looking at the future supply data from S&P, as well as Albemarle’s demand projections, a shortage seems almost completely unavoidable. Nothing short of a complete collapse of demand would be able to prevent it, which is not exactly something shareholders of Lucid or Rivian should be hoping for.

Nickel & Cobalt

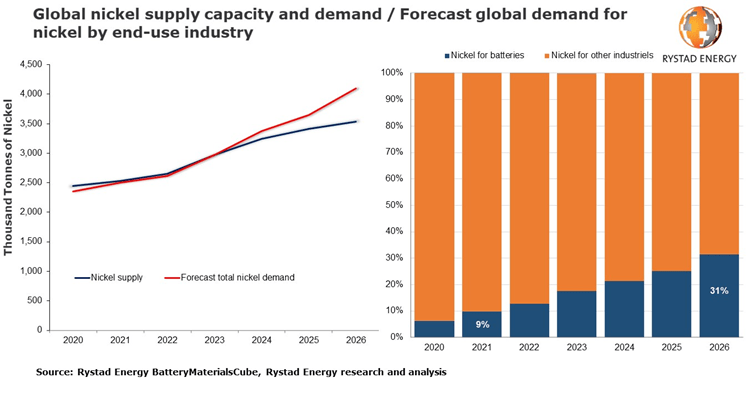

It may not be immediately obvious why nickel supply could struggle to match demand. After all, there were 3.3 million tonnes of nickel mined in 2022 and only 5% went into EVs. But the disconnect here lies with the quality of nickel produced.

The vast majority of nickel is used in the production of stainless steel, which doesn’t always require a particularly pure product. But, in order to be used in EVs, nickel needs to meet Class 1 certifications, stipulating a purity of at least 99.8%.

Currently, 20% of the world’s Class 1 nickel comes from one Russian company, Norilsk Nickel. While most of their nickel isn’t actually even used in EVs, instead being utilized by other industries that require high-purity nickel, it’s still important to be aware of what the Class 1 nickel supply looks like. At the end of the day, all consumers are competing from the same pool and, currently, this presents a looming geopolitical threat.

Even without geopolitical risks, however, nickel supply will struggle to match demand. While 46% of global nickel production meets Class 1 standards, only 20% can be converted into the nickel sulfate needed for battery production.

That’s because much of Class 1 nickel is ferronickel, which is great for stainless steel, but not really for cathodes. While China has begun to convert ferronickel into cathode feedstock, the carbon intensity of this process has raised some concerns. Considering all of this, it’s not too hard to see why many analysts are forecasting a long-term nickel shortage for EVs starting as soon as this year.

Rystad Energy

Cobalt is a completely different beast. Goldman Sachs (GS), which has historically been one of the most bearish analysts in the EV metals industry, projects that cobalt supply will be the most limited of any other battery metal. The bank expects that demand will exceed supply by a margin of 33% in 2030, far more than any other battery metal.

While I believe the bank has significantly overstated future cobalt demand, contributing to a more extreme shortage in this projection, you’d be hard-pressed to find an analyst that is confident in the long-term cobalt supply. But not only is supply limited, it’s wrought with heinous human rights violations.

Over 70% of the world’s cobalt comes from the Democratic Republic of the Congo (“DRC”), where labor laws are hardly enforced. This has resulted in a workforce that is almost 15% child-based. These children are often given the dangerous job of navigating the narrow, hand-dug, tunnels constructed by men working for $0.65 per day.

More recently, the presence of uranium at many of these mines has been linked to a number of miscarriages and severe birth defects. Other impacts of the mines include pneumonia, asthma, or even lung cancer from breathing in particles of the metal. Vomiting, loss of vision, heart issues, or thyroid damage can be a result of consuming the metal, which often works its way into local waterways given the complete lack of environmental protections in place.

Partly due to this plethora of human rights violations, many companies are now looking to source cobalt from other nations, such as Canada, but the production capacity just isn’t there yet. Even if other nations are able to develop more cobalt resources, there’s no getting around the fact that the vast majority of the world’s cobalt reserves are located in the DRC.

Battery Alternatives

When it comes to lithium, there simply is no alternative, further exasperating the looming shortage. While CATL, the China-based leader of battery manufacturing, has plans to begin production of a sodium-ion chemistry by the end of the year, more recent comments indicate that the battery will not be independent of lithium.

In order to achieve the range requirements of the average consumer, CATL was unable to completely forgo the superior energy density of lithium. Instead, the sodium-ion battery will contain a mixture of sodium and lithium. Furthermore, the chemistry appears to be positioned as a low-end alternative to LFP for minimal-range city cars.

LFP, or lithium ferro-(iron)phosphate, batteries are already the budget option in EVs, occupying the bottom of the cathode chemistry cost curve. The cathode sacrifices range for improved internal stability, but it’s really the cost, not the stability, that has made it so popular recently.

Therefore, as you may imagine, this trade-off really only works for entry-level EVs. So, ignoring the fact that sodium-ion batteries aren’t even in production yet, neither Lucid or Rivian currently produce anything with a price tag below luxury.

Granted, both companies do plan on introducing cheaper models as they increase scale. But sodium-ion batteries look to be far too range-limited for either company to ever introduce them. Instead, the application of sodium-ion batteries looks set to be within the niche Chinese market of compact city cars.

Fortunately, unlike lithium, there are alternatives to cobalt and nickel. The aforementioned LFP cathode is one such option and it has been steadily growing in popularity in the West, after taking about 50% of the market in China. This growth is coming at the expense of market-leading nickel-manganese-cobalt (“NMC”) and nickel-cobalt-aluminum (“NCA”) cathodes, exalted for their unbeatable energy density.

The low-cost LFP chemistry is a great option for mass-market EVs, providing good enough driving range in exchange for a significant cost reduction. While the vehicle lineups of both Rivian and Lucid consist of, exclusively, luxury vehicles, they do also both have plans to eventually manufacture cheaper cars. LFP could, therefore, be a viable chemistry for their entry-level vehicles, adopting a similar strategy to Tesla (TSLA), which has introduced LFP cells to the lowest trim levels on its Model 3 and Model Y.

However, for higher trim models, it may be more difficult for the companies to find a viable chemistry. In an effort to reduce reliance on cobalt, and retain some of the energy density of high-nickel cathodes, a few companies are currently researching a manganese-based cobalt-free cathode. Volkswagen had originally hoped to begin commercial production of the technology this year but, with few updates since their 2021 Battery Day presentation, it’s safe to assume that the technology has been delayed.

The chemistry, a manganese-nickel-oxide (“LMNO”), also isn’t as energy dense as NMC or NCA. And while it may be able to make up for that with high voltage capabilities, none of this matters unless it can be produced commercially. More importantly, as far as Rivian and Lucid are concerned, this still doesn’t solve their lithium or nickel problems.

Manufacturing Impact

Even if we’re looking only at the lithium market, which is where I see the biggest threat, things don’t bode well for Rivian and Lucid. A 25% shortage will force EV manufacturers to compromise on output. But, unfortunately for our two startups, not all OEMs are playing with the same cards.

General Motors, for example, has already secured all of the battery raw materials it needs to produce 1 million EVs per year through 2025. After a recent investment in Lithium Americas (LAC), it has now secured enough lithium for an additional 2 million EVs through 2041. Granted, General Motors has done a better job than most in securing its battery metal supply chain, but most other manufacturers have started to implement similar precautions.

Over at Lucid and Rivian, focus remains on ramping production. Don’t get me wrong, that’s an important goal to execute on, but if there aren’t any raw materials around by the time they get it figured out, it might not matter.

It’s not as though either company is oblivious to this issue, but they simply can’t afford to fork over the hundreds of millions, or even billions, of dollars that more established automakers are throwing at this problem. Especially when they both continue to burn cash (Lucid, Rivian).

Even the OEMs that aren’t pouring money into mines at least have the bargaining power that can only come with decades of experience, manufacturing millions of vehicles. That, again, is something that neither Lucid or Rivian have.

So the 25% lithium deficit won’t impact every automaker the same, some may not even need to cut production. But in order for that to be true, others will be forced to take the brunt of the burden. Lucid and Rivian look poised to do just that.

Nickel and cobalt shortages could force them to introduce cheaper models before they’re ready to do so. Or, more accurately, before either company is producing at a large enough volume to do so profitably. With shortages for both metals likely to begin by 2024, it seems highly unlikely that either company will be in a position to respond.

Last August brought the latest delay to Lucid’s electric SUV model. The car, which was initially slated for a 2023 release, now may not hit the streets until 2025. With the company’s more affordable models expected to come only after the SUV’s debut, there really looks to be no chance that Lucid can introduce more affordable models within the next few years.

Rivian is in a bit of a different boat. While they too will struggle to get truly affordable EVs on the road within the next few years, Rivian has already committed to an LFP strategy. The company has introduced standard-range versions of its R1T and R1S models, which start at $73,000 and $78,000 respectively, and will be available starting in 2024. For its delivery vans, the company has already started using LFP cells.

While it’s still unclear how popular these standard-range batteries will be, seeing as production has not yet begun, I have mixed feelings about them. While I think it’s good that Rivian has begun to implement LFP, reducing its dependence on nickel and cobalt, I also think that a 260-mile range in a $73,000 vehicle is a hard sell. It just doesn’t feel luxurious.

Take the Chevy Bolt, which offers 260 miles of range for just $27,495, or Tesla, which has refused to offer its Model S and Model X vehicles with LFP batteries.

Sure, the Rivians have a lot more bells and whistles than the Bolt, but that still doesn’t necessarily justify the vehicle’s $73,000+ price tag. In any case, while Rivian may be slightly better equipped to handle a nickel and cobalt shortage than Lucid, neither company looks remotely prepared to weather a tight lithium market.

Business Impact

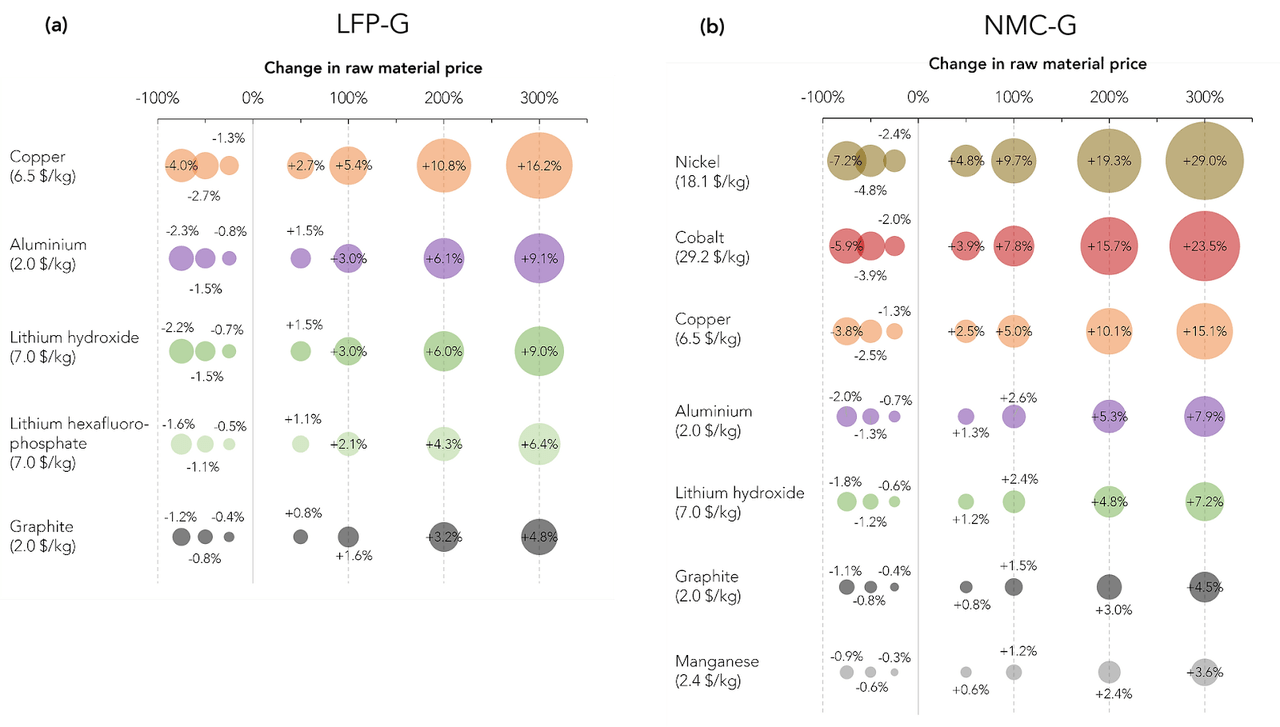

For both companies, the best-case scenario would be that they are able to dramatically overpay for their raw metals, thus avoiding cutting production. The figure below demonstrates the impact of higher raw materials prices on the overall price of manufacturing a battery cell, albeit with some outdated prices. I’ll be using this to quantify the impact for Lucid and Rivian.

Storage Lab

Let’s focus on lithium, as it’s the only metal that there’s really no avoiding and I believe it will have the tightest market. In the above figure, an estimate of $7 per kg is used for lithium hydroxide. Currently, lithium hydroxide prices are ~$70 per kg on the spot market. Following the above estimates, lithium prices have therefore increased the cost of batteries by 21% for NMC cells, or 46% for LFP cells (including lithium hexafluorophosphate).

For those of you that say these prices are unsustainable, I agree. That’s why it’s important to understand the difference between spot prices and contract prices. Look at Allkem (OTCPK:OROCF), which reported an average sales price of $46,706 per tonne of lithium carbonate during the final three months of 2022. During that period, spot prices peaked at $87,384 per tonne and never fell below $74,664 per tonne, which was hit on October 1st (the first day of the period).

So did Allkem do a bad job selling its lithium? Not at all. It just sold most of it in bulk, creating a deviation from the spot prices. That means, even in tight markets, automakers with long-term supply contracts have a bit of protection against high lithium prices.

Because Rivian and Lucid do not have any long-term supply deals, and are unlikely to be able to arrange any, they will likely be forced to purchase their lithium close to, or at, spot prices. This will hamper the companies’ ability to turn a profit and maintain competitive pricing as they try to introduce more affordable models.

In 2022, lithium supply was in a deficit of just 5,000 tonnes, or .78%. If spot prices of ~$70,000 can be sustained in that environment, I really don’t think it’s much of a stretch to assume that they can be sustained if there is an 800,000-tonne deficit, or 25% shortage. As such, both companies will likely have to raise the prices of their vehicles down the line to maintain profitability.

To make matters worse, this tight market may also make it harder for vehicles produced by Lucid and Rivian to qualify for the $7,500 tax credit as outlined in the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act. To do so, at least 40% of critical materials in the battery need to be sourced from the United States, or countries that it has a free trade agreement with. This 40% threshold will rise to 50% in 2024; 60% in 2025; 70% in 2026; and 80% in 2027 and beyond.

Additionally, at least half of the vehicle’s battery components need to be manufactured in North America. This also has a growth clause, moving up to 60% in 2024 and 2025, eventually reaching 100% in 2029. With around 60% of lithium chemicals currently coming from China, and the vast majority of new projects set to come online in Argentina, it will be incredibly difficult for either company to meet this first standard.

China, Argentina, Indonesia, and the DRC, do not have a free trade agreement with the United States, meaning the battery metals from there will not help automakers qualify for the full tax credit. This problem will only be exacerbated upon the introduction of less expensive models. With higher raw material prices, Lucid and Rivian won’t be able to absorb the impact of the tax credit within their pricing model either.

These two problems will combine to reduce both companies’ competitive strength and ability to maintain profitability. Unfortunately, as I’ve already noted, this looks like the best-case scenario for both companies. The more dire, and likely, scenario is that both companies will ultimately be forced to limit production.

Financial Impact

Lucid’s current cash position (as of September 30) sits at $2.755 (including $1.491 billion of U.S. treasury securities). Including a $1.5 billion equity raise in December, the company’s cash position is probably closer to $3.521 (following analyst estimates). That’s not too bad; it should buy them at least another year or so.

According to estimates provided by FactSet, Lucid is expected to burn through another $3.93 billion through 2024. So, even without any additional roadblocks, Lucid will almost certainly need to raise more capital.

There’s also the $1.991 billion in long-term debt to consider. This debt stems from a $1.75 billion bond offering from 2021, now worth $2.013 billion in liabilities, and it comes due on December 15, 2026. This introduces the risk of insolvency, upping the stakes a bit. Granted, bankruptcy doesn’t seem terribly likely, but avoiding it will come at the cost of significant shareholder dilution.

Moving on to Rivian, we see a bit more extreme situation. While the company has more cash on hand, $13.272 billion (as of September 30), it’s also burning it at a much faster rate. Analysts expect the company to burn through an eye-watering $10.096 billion through 2024, on top of an additional $1.924 billion in the final quarter of 2022. While there’s no debt to worry about here, that aggressive burn rate would leave the company with $1.252 billion to start 2025.

This may be an even worse position than Lucid, which is at least showing signs of reducing its burn rate. Lucid may even post a quarter or two of profit in 2025, whereas Rivian will almost certainly fail to do so. Still, I’m not sure being the better of two bad options is really something to celebrate.

Keep in mind, we haven’t even started to factor in the impact of raw material shortages. Now, this impact is a bit difficult to quantify given the multitude of different scenarios that may emerge but, at this point, it should be abundantly clear how weak both companies’ financial positions are.

I also want to stress how critical the long-term growth story of both companies is. While part of this means physical growth, as in higher production volume and new facilities, it also means that investors expect the companies to eventually start churning out big profits. What else would $17+ billion valuations imply?

That’s where I think the real issue lies. I don’t think either company will become insolvent. And, while not immune from some reductions, I don’t think either company will be forced to completely cease production. But I do think that both companies will fail to meet revenue and profit targets, resulting in valuations that are far too high.

This is cataclysmic for companies trying to sell a story of growth.

Investor Takeaway

For both Rivian and Lucid, investors tend to point toward the long-term outlook to justify their sky-high valuations. But I believe this resource risk is grossly under-accounted for, especially because it could completely derail any growth plans that either company may have. Execution risk is already high, and this additional layer of risk makes both companies’ valuations unacceptable in my opinion.

While I still believe that Lucid is really the only EV manufacturer that is making meaningful improvements to the electric drivetrain, I just don’t think that’s enough to justify continuing to own the company. Long-term investors should be incredibly concerned about the implications this shortage carries for the future of Lucid Motors and its capability to reach its ambitious targets.

As for Rivian, there’s little about the company that impresses me beyond its ability to lock down a supply agreement with Amazon (AMZN). But even that may end up causing more harm than good if Rivian continues to have difficulty scaling and reaching cost targets. For investors on the fence of either company, let this be the final nail in the coffin keeping you away.

Disclosure: I/we have a beneficial long position in the shares of LAC, GM either through stock ownership, options, or other derivatives. I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it (other than from Seeking Alpha). I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.

While Rivian and Lucid may not be the best ways to take advantage of booming electric vehicle demand, there are plenty of other ways to play the industry. At Green Growth Giants I provide investors with a model portfolio, and regular articles, to uncover the companies with the greatest upside in the green revolution. Try a two-week free trial to gain access to the #1 clean investment subscription and see how you too can beat the market.